Marcel Wanders is a busy man. Just eight weeks ago we sat in this very spot: the lobby of the Andaz in Amsterdam, a lavish hotel his studio completed in 2012. Since then he’s flitted between countries—mostly nearby, he says, playing things down, with the exception of Goa in India. Not only that, he’s between houses and studios. Busyness is a constant in the Dutch designer’s life. After being booted out of Design Academy Eindhoven in his younger years, he went on to juggle two courses: one at the art academy in Maastricht and the other in Hasselt. Then he attended ArtEZ University of the Arts in Arnhem. And as if life wasn’t hectic enough, he tinkered with his own projects alongside his studies.

While his fellow graduates searched for their first big break, he already had two products being manufactured by professional companies. He opened his Amsterdam studio in 2000, three years after completing his now famous Knotted Chair and one year before launching Moooi with Casper Vissers. Since then he’s juggled two guises: Marcel Wanders the designer, and Marcel Wanders of Moooi. He’s also secured an MBA, set up start-ups in San Francisco, and become an advisor to two venture capital firms. And there’s much more in this man’s brain, much of which is too soon to reveal. Although a lot is up in the air, you get the sense that Marcel is in his element. “I’m not so good at leaving things,” he says. “I’m better at taking them on board.” So, just how does he do it all?

You’re currently house-hunting in Amsterdam, but I recall you living in Milan at some point. How did moving to Italy come about?

I was in Milan for a year in 2016. I also spent a year in San Francisco and in Budapest, and I received my MBA from INSEAD in France four years ago. I’ve been around a bit. It all started because my girlfriend at the time really hated Amsterdam. Even though I have good reasons to be in Amsterdam—my studio and my daughter, for two—I thought it was a bit weird to have only lived here. By then my daughter, now 20, was old enough, and I could work remotely, so at some point I said, “OK, OK. Let’s do five years, five cities.” The first stop was San Francisco. Two weeks before we left, the relationship ended. She stayed in Amsterdam and I moved to the U.S. alone. While there I was able to set up start-ups—a world I find super interesting—and become an advisor to two venture capital firms. San Francisco is one of the coolest cities in the world.

The Mondrian Doha in Qatar (2017) is a five-star destination designed by Marcel Wanders. From the atrium (top) to the pool (bottom), each space has its own identity while reflecting local patterns, Arabic writing, and historic souks. In the pool area, ornate stained glass adds to the luxurious experience.

I count only four locations, not five…

I was needed back in Amsterdam frequently last year, and my daughter now lives with me. I’m going to park the fifth year for later.

How do you manage to run your studio from a distance?

While living in San Francisco I would return to Amsterdam every five to six weeks for one week—quite often. Since I knew it was only a year I didn’t want to push it further than that, but if I’d stayed longer I would have come back less frequently. That said, I had daily conversations with my studio. I don’t manage the studio; I oversee the management. If you oversee really well, you don’t have to manage at all. You know what’s happening because they’ll let you know. I think it’s important that a management team is committed to the core, to the source. If they love the vision of the company, they won’t give up. Gabriele Chiave and I take the creative lead. I discuss everything with him—and vice versa. We understand each other through a WhatsApp message and a couple of sketches. We get it. We’ve worked together for a while and can be very clear with a few words, a few lines.

So the working anywhere and everywhere movement has afforded you a more flexible lifestyle?

Absolutely. It would not have been possible a few years ago, at least in terms of technology. But I’ve also been preparing the studio with the right people for quite a while. I was ready and my studio was ready. And technology happened to be ready, too.

That said, you will have somewhat of a base here in Amsterdam. What are you looking for in your new home?

It’s quite a difficult city. A lot of people like typical Amsterdam canal houses. I don’t. I want something atypical. That’s my only criterion.

The Parents collection (2016) is made up of thoughtfully designed baby furniture that fits seamlessly into the home while adding a bit of whimsy.

Although it’s quite hard to find something atypical in Amsterdam.

Exactly. I try not to be too specific with what I want because then I’ll never find it.

It must be expensive to bounce around the globe. Do you think there’s a relationship between financial independence and creativity?

I used to place a lot of value on freedom. That’s the wrong idea. If creative people think freedom is really important, then maybe they should think again.

Freedom in terms of financial freedom?

Any kind. Freedom feels like one of the words for creatives, right? But in a way it’s like a bank account full of money. It sits there; it does nothing for you. If you have a bank account full of money, the value of that bank account lies in spending the money. Spending your freedom on something is relevant; having freedom is nothing. It’s a lack of commitment to anything. It’s indecisive. If your freedom has more worth than your opportunities or your commitments, then what do you have? Nothing. You need to make sure you’re committed and connected to the world through things that are more important than freedom. That also goes for traveling, money—all of these things.

But yes, I am traveling the world—sometimes too much, which is when I pull back. At this point in my life money doesn’t play a role, but I’ve also never traveled just for fun; I travel for my business. There’s money being made while I travel—it’s more of an investment than an expense. I’m not the kind of person to go traveling for inspiration. People who think they’re more creative just because they travel? I have to disappoint them. I also don’t believe if you have more money you’ll be more creative.

Read more art direction, furniture, product, and interior design stories at Sixtysix.

Creativity can also come from limitations. I know a lot of designers who much prefer to receive a really strict brief than something incredibly open, the latter of which is more like your idea of a bank account full of money.

Creativity comes from having real clarity about what you want to do. The inspiration for creativity comes from inside, not from outside. From outside you might get the question: Can you make a chair? That’s not inspirational. But if you want to design a chair that’s more romantic than other chairs, or one that’s lighter than any other chair in the world, if you want to make a contribution that goes beyond the rational world, beyond our culture? Now you get excited; you get ideas. Because you’re asking yourself an interesting, new question nobody’s ever asked before. If you ask yourself a boring question everybody else has already answered, you’re not going to answer it better. If you ask yourself a question that is truly different than what others have asked, or you demand from yourself a contribution that’s truly different from what others have done, now your answers will be interesting and inspiring. But the inspiration therefore lies in the question you ask yourself. Most people ask really dumb questions. How can I make some money? How can my client be happy? Those aren’t the right questions. If you ask questions that are stupid, you get stupid answers. It’s logic.

Marcel teamed with O2TODAY in 2018 for the O2SafeAirMask, a personalized, customizable air mask.

Can you share any practical advice for young designers who may be struggling financially?

When I was a kid, I did everything to make enough money to survive. But then at night and on the weekends, I’d do my own stuff. People always said I was so lucky to be able to experiment so much, but who do you think pays for that stuff? Clients? Never. You pay for experimentation. Trying to be smart enough to make money makes you grow. It’s complicated. You might have to do some projects you don’t even like, but they allow you to come up with things you think are really important in your spare time. If you want to be a designer, you better decide to work hard. It’s not going to happen otherwise. And if you want to find interesting questions to ask yourself, you have to decide to be really honest with yourself. You can lie to the world, but you have to be honest with yourself. That’s the difficult part, because it will make you lonely. It’s not an easy place. The honesty that comes with an original mind comes at a price. People might not like you.

You’ve always kept on top of young talent, helping to launch the careers of some now renowned designers. Is that still a big part of what you do?

Big, yes, and growing. I like doing things that make a difference. If I help Ross Lovegrove make a chair, then that’s really cool and I’ll feel good about it. But what I feel even better about is doing that with a kid who’s never made anything and will never be seen if I don’t help him. Young creatives deserve chances. Of course they can find their own way—and if they’re good then they will find it—but if I can help them I’m happy to. I’ve been in their shoes.

Has anyone specific caught your attention lately?

Rick Tegelaar. He may not be a kid anymore, but I think he’s really great.

“I usually sketch in my head. Sometimes I’ll make a drawing, but that’s usually only when I really know what it will look like.”

Do you still go to graduation shows to scout around, or have you changed the way you discover new talent?

My eyes and ears are open wherever I am. I see stuff; I hear stuff. The world is pretty transparent these days. You have to try really hard to hide your work so I don’t see it. If someone thinks they’ve been overlooked, they’re more than welcome to email me. My address is easy to guess.

What about advice for designers trying to get a product manufactured by brands?

It’s both a difficult and fortuitous time. There are so many young designers out there, but so many of them design completely irrelevant things. My advice? Design something relevant. There are now so many systems online for designers to be seen, to get their work out there. So many opportunities to make and develop and sell your own stuff. It feels like the possibilities today are endless. You can do whatever you like.

Do you think designers still need brands to help them launch their products on an international stage?

I do think brands are helpful. Brands have a podium, and podiums are important. Our audience is happy to be helped with their decisions. People tune in to a certain radio station because they think they’ll hear good music. And then when they hear the music they know it’s good because it’s from that radio station. The same happens in the design world. Maybe you’re a dentist who has no idea what’s classed as “good design,” but you want to design a house, so you go to the right brand. If designers want to use a podium, that’s great. They can do it without one, but I like them. I like to make them for other people and I have done it all my life. There’s Moooi, of course, and I’m currently working on a new one.

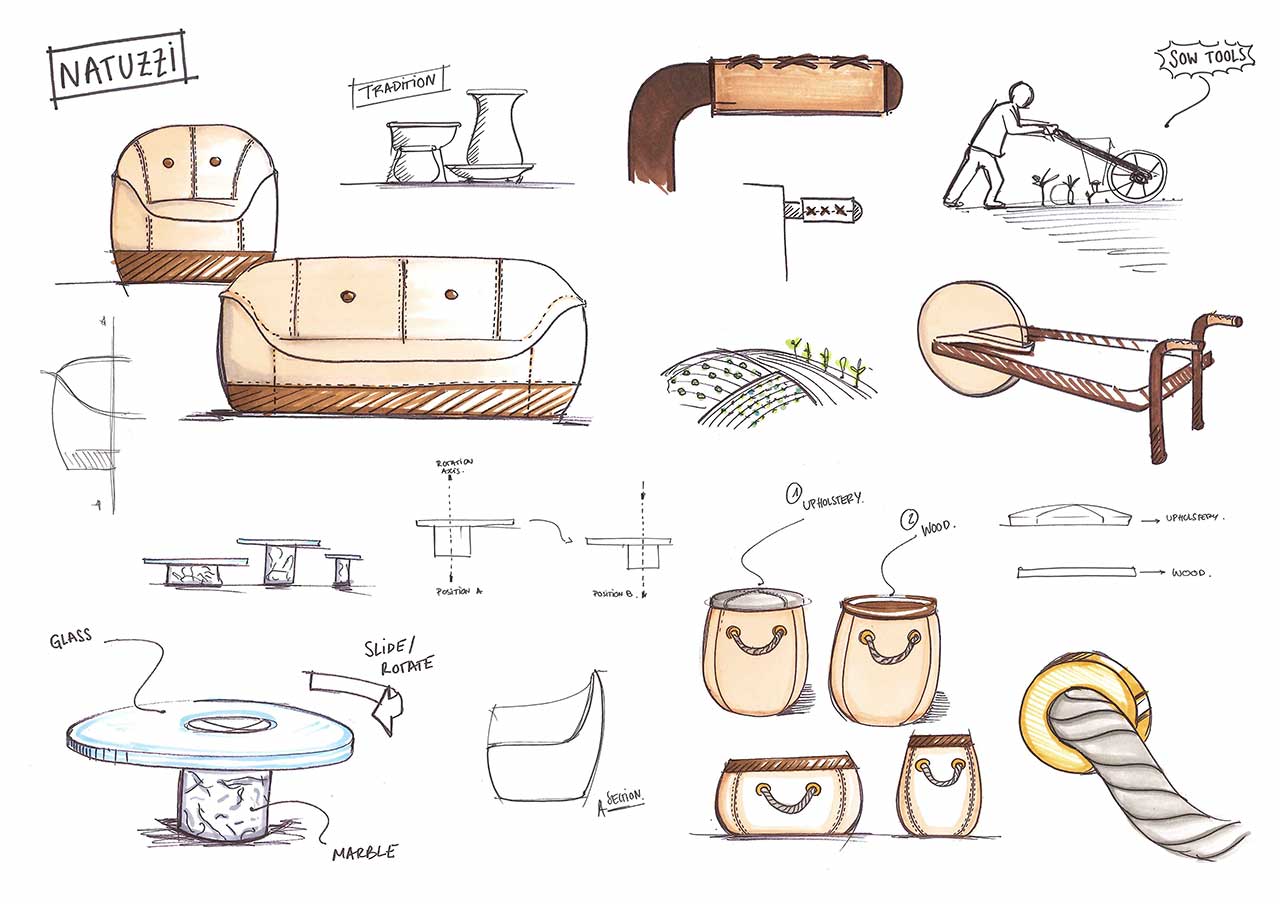

The collections for Natuzzi are inspired by the rich browns of the earth, the white houses of Ostuni in Italy, and the silvery tints of olive groves, to name a few.

Casper Vissers stepped down from Moooi two years ago. How did that come about? How did it affect you, and what did you learn from that experience?

Casper was a fantastic CEO for Moooi for 15 years. He felt it was time to do his own thing for his own company, to be the creative director and the CEO. Perhaps he also felt the company was the right size for him and he didn’t want to be part of something bigger. I completely understood. At some point you just want to taste something different, even if you like what you’ve always eaten. If you have a job you can just get a new one. It’s harder when you own a company. We worked together to make the change possible. I was scanning my surroundings to see if there was someone I already knew and could trust to become the new CEO. One idea was to ask the CEO of Marcel Wanders Studio, Robin Bevers. For Robin it was a step up, into a bigger company. I trust him completely and I thought he could do it. In fact, he’s now the CEO of both companies. For the first two years it’s been high on my priority list to check that everything is running smoothly. So far, so good.

You’ve also said you’re not a one-man band, that you don’t do anything alone for Moooi or for your own studio.

I do nothing; I’m sitting here talking to you. While it was great having Casper as a partner in Moooi, I’m OK having no partner, too. I’d love to have a new partner, but it just hasn’t happened. One could come along tomorrow—I don’t know. I work easily with other people because I let them do what they want. And it’s not that I’m a complete moron. I went to business school; I know what has to be done. I can follow processes from a distance.

The Globe Trotter collection, a collaboration between Marcel and Roche Bobois, on display at the famed Cirque d’Hiver event space in Paris. Photo by Stevens Fremont.

Being able to rely on others must help you to feel as if the load is shared, too?

If something goes wrong, ultimately it’s my fault. But I do feel that I’m sharing my responsibilities with others. I also feel really connected to my team—and vice versa, I think. Marcel Wanders Studio is loved by the people inside it. Of course there are those who see it as a vehicle to spending a few years in Amsterdam, but the managers have been with me for 12 or 31 or 31 years.

Do you feel like you work 24/7?

Honestly? I feel like I never work.

Your work doesn’t feel like work?

No.

Are there things that keep you up at night, or concern you?

Of course. Well, not concerns but excitement—the excitement of sketching a new idea, for instance.

Do you have a typical workday, or is nothing typical for you?

I wake up; I meet people; I talk with them; I go to sleep. This could happen anywhere in the world. I have periods in which I travel lots and travel less. I could be sitting on a beach or in the studio. Maybe I say this all because I don’t want to be typical. But there’s always a lot of thinking, talking, eyes, ears. A lot going in and out. I’m active, very active. Maybe that’s the constant.

- Marcel created the ‘Agronomist’ and ‘Oceanographer’ collections.

- The designs are based on the landscape, architecture, and lifestyle of Puglia in Italy.

Do you have any design rituals?

Most of my designing is done through writing—more so than drawing. I usually sketch in my head. Sometimes I’ll make a drawing, but that’s usually only when I really know what it will look like. Otherwise the first sketch I might make is when someone’s sitting next to me and I’m explaining what I want. Something to help them understand the design. And by that point, it’s already 70 to 80% finished.

Have you ever really struggled with a project?

I remember doing a project around 25 years ago. I made a small pin for my then girlfriend who was extremely sick. It said “held,” or “hero” in Dutch, and represented her incredible strength through all her struggles. I saw how important it was to her based on when and where she wore it. At some point I wanted to make the project bigger, but I never knew how. I didn’t have hundreds or thousands of heroes. Producing it and selling it for 25 bucks in a shop and explaining the story to everyone—that didn’t make sense. Then, 18 years later, Libelle—the biggest magazine in the Netherlands—asked me to design their cover. I’m not a graphic designer, I thought. Why would I do your cover? A week later I called them back to tell them I wouldn’t do their cover; I’d do their entire magazine. “I’ll be the guest editor and art director,” I said. “The topic will be: What do you really and truly value in life? What traits do you love in other people—and maybe in yourself? Are there people in your environment who exemplify those traits, people who are your heroes? Could you give them a bit of acknowledgement? Could you give them this little pin that sits inside this magazine?”

We designed the whole magazine around presenting this tiny pin, of almost no material worth. Every magazine had one. You see? The question sat in my brain for 18 years, waiting for the subtlest hint of a solution. A magazine asks me to do a cover: That’s how little I needed for the penny to drop. You don’t have to give up, because you might just find a way. If a project is important enough, it will stay in your mind. The projects I really struggled with never became finished projects. They were failures. But I have this notion that you never have to lose a game if you never leave the field. In that way, I’ve never lost.

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of Sixtysix with the headline “Marcel Wanders Asks the Right Questions” Subscribe today.

Photos and sketch courtesy of Marcel Wanders unless noted.