“Do you mind if I ask you a personal question?” Such are the words uttered by the AI HAL in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: Space Odyssey. Just like the character of the movie he loves, Vincent Fournier isn’t afraid to get weird. Rather, the French artist and photographer explores a universe that’s just outside reality. His surreal photography enjoys the ambiguity of fictional elements and the philosophical thrill of imagining what the future might look like.

The results are ongoing pieces like “Post Natural History” or “Space Project.” “My images are a mix of purely documentary elements and very carefully constructed staging in which each detail depends on the overall composition,” he says. “Space exploration’s emblematic locations are like cinema sets where Tintin might meet with Jules Verne in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.”

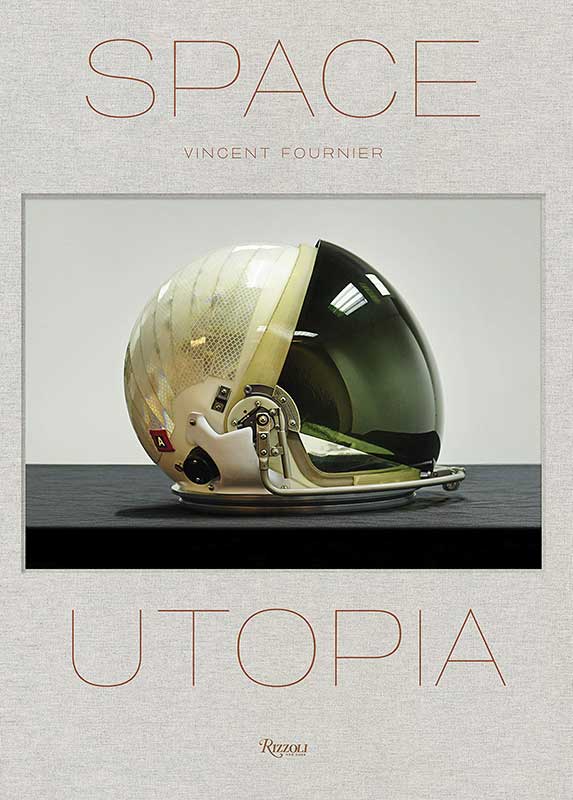

These imagined sets come to life in Vincent’s 2019 book, Space Utopia, itself a nod to Kubrick with an elaborate white case on the collector’s edition he says represents the silence in space. You can see Vincent’s work everywhere from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the Centre Pompidou in Paris to Mori Art Museum in Tokyo.

Although he’s been spending time in quarantine at his country home and studio in Burgundy, we caught up with Vincent pre-COVID at his perfectly Parisian apartment near Carreau du Temple, where he told us about how he works and what he loves about the future.

Let’s start at the beginning. I understand sociology was part of your studies. How does that influence your work?

It certainly influenced the documentary aspect of my work, the neutral approach I choose, the distance I maintain with the subjects. My photographic style is reminiscent of the documentary film style: no distortion, a neutral approach, no effects. And just like with documentaries, there is room for fictional elements. The idea is also to build an ambiguity with fiction. When I was a student, my focus was both sociology and cinema. I was particularly fond of sociological documentaries. Then I applied to ENSP (École nationale supérieure de la photographie d’Arles) and got in.

“Mars Desert Research Station #4 (MDRS), Mars Society, San Rafael Swell, Utah, U.S.A., 2008.”

This Mars Desert Research Station is hidden in the southern Utah desert, where astronauts in training test field procedures and new technology. Photo by Vincent Fournier

- Photo by Elodie Daguin

- Photo by Elodie Daguin

How would you define what you do today? You are a photographer, but you also work with installations and sometimes sculptures.

I build a conversation with different tools, different mediums. It is often photography since it’s my medium of choice; I have a one-of-a-kind relationship with photography. But I can adopt different tools for different projects. It really is a technical matter. For instance, I did a piece called “The Unbreakable Heart.” It was the third cycle of the “Post Natural History” project. It was a golden sculpture shaped like a human heart; I had to work with a jewelry workshop. I designed the piece first and then it was built, in the technical sense of the term, in this workshop. It took about 200 hours of hand labor to make it.

It’s true though that the starting point is often photography because, in that instance, it was a photograph I made that turned out to be the starting point for the sculpture. So even if the result is not a photography project, that medium is always part of the construction. Well, it depends actually. The first cycle of “Post Natural History,” it was more collages and photo montages. That’s still photography. I had gathered flowers and plants in different groups before regrouping them in order to make chimeric beings, not unlike an exquisite corpse.

“Beijing Military Museum (MMCPR), DF-1 ballistic missile, China, 2007.”

Vincent’s work also captures space exploration artifacts from all over the world, like this DF-1 ballistic missile in China. Photo by Vincent Fournier

Vincent’s sculpture “The Unbreakable Heart” is made of 18-karat gold, topped with jewels, and laced with red “veins.” He collaborated with a Paris-based jeweler on the project. Image courtesy of Vincent Fournier

What about “Brain Cloud?”

If you consider a piece like “Brain Cloud,” there is no connection to photography whatsoever. The starting point here was more of a painting—a painting of a cloud by René Magritte. Photography was not part of the process at any point. Here it was more the painting, and the surrealist movement in painting. The surrealist aspect is quite present in my work in general.

What do you love about the future, or futurism in general?

It truly is an obsession I have for the future as a concept, as well as the way in which it’s represented. It can be the future we all apprehend, the future of tomorrow. As well as a parallel future. Or the way the future was imagined in the past. It can have different levels. What interests me first and foremost is the aesthetic aspect, the form it takes. There is truly a philosophical thrill in questioning the future. It questions what cannot be seen, where we come from, what’s our place in the universe … I am really fascinated by this philosophical aspect.

It also interests me because the future imagery has something of an in-between universe. An intermediary space between two worlds. Between the past and the future. Between what is real and what is imaginary. This all creates an interesting tension and a non-space where stories can be invented. Just like my work, almost everything is real, yet there is something in the way I take pictures that can be staged. It can be quite absurd, often aesthetically oriented.

Related | Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec on Making (and Breaking) Objects Every Day

That can particularly be seen in “Space Project.” Could you explain how this all started?

It started in 2007 with photographs I took in Hawaii, at the Mauna Kea Observatories. I was fascinated by the ambivalence of this landscape, which combined two opposites. The eruption of futuristic architecture in a very rough landscape. The contrast was very strong. In Hawaii, it started as an aesthetic choice. Then I was fascinated by this observatory that observes the invisible. It listens to the sky; it questions the universe. I then went to a lot of observatories, especially in South America in the Atacama Desert, for instance. It’s the driest desert in the world. As I started looking at the sky, I felt the desire to go there, to explore that part of things as well, so I extended the project to the space conquest.

“Robonaut 2, NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC), Test facility, Houston, 2017.”

Robonaut 2 is a dexterous humanoid robot built to help humans work and explore in space. Photo by Vincent Fournier

- Vincent in his Paris apartment. Photo by Elodie Daguin

- “Space Utopia” by Vincent Fournier. Image courtesy of Rizzoli

And you kept on exploring with photos you took at NASA?

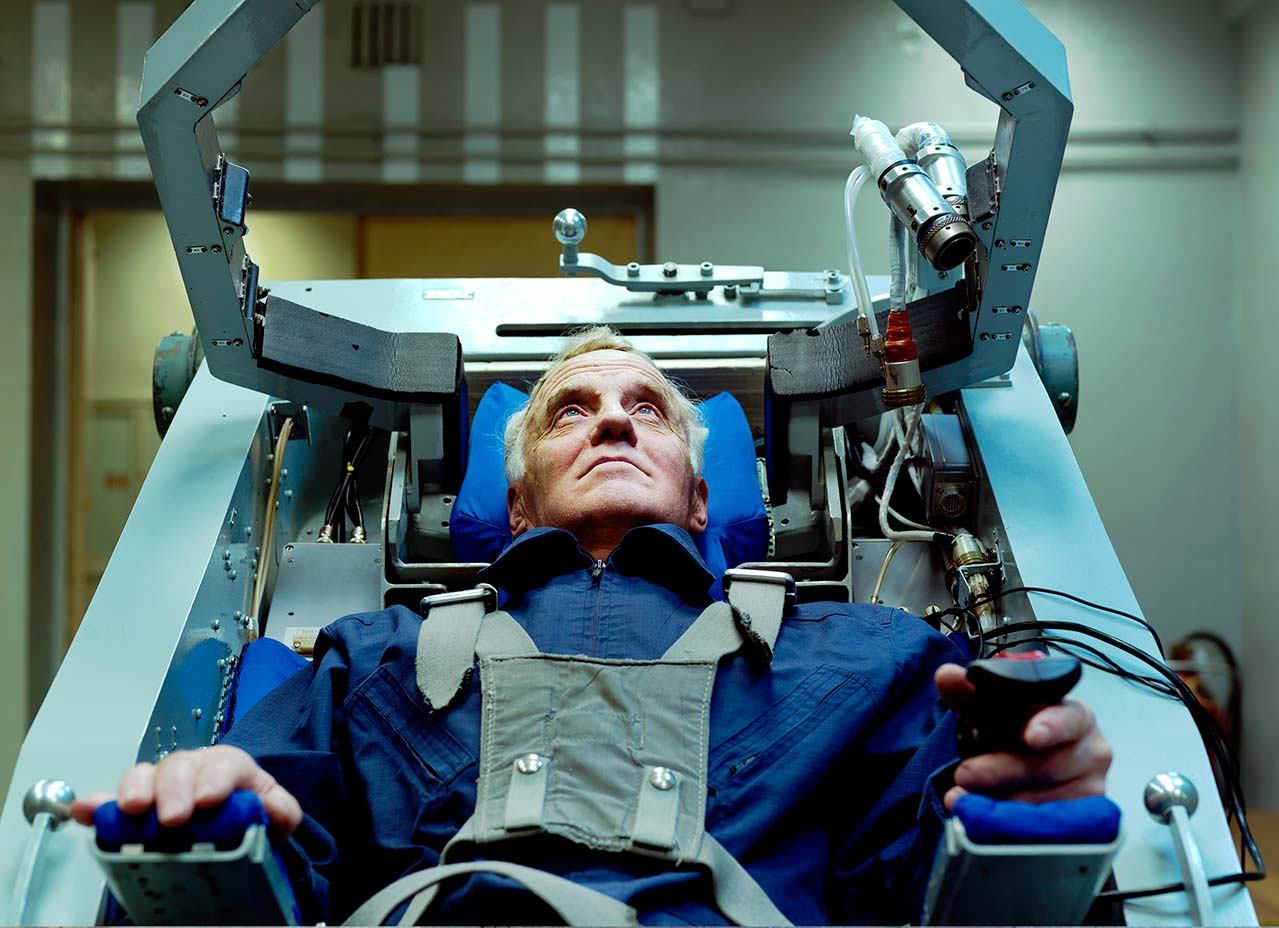

This project travels in time as it tells the story of the space adventure from Apollo to today, but it is also an around the world journey, visiting the NASA stations, as well as stations in Russia, South America, and more recently in China and India. The space project is not about photographing the spectacle of a spaceship lifting off. It is more about the in-between, or what is not often seen. It focuses on what is off-screen.

Related | How Marc Fornes Blurs Art with Architecture

Speaking of off-screen, how does cinema influence your work?

Cinematographic references feed my work since I studied cinema. Of course 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick is a central piece. The movie is a great example of multiple times and spaces. I encourage you to watch the last scene again if you haven’t in a while. The cosmonaut finds himself in a [neo-classic environment]. I really enjoy this type of construction. It’s also a movie building a vision of the future in the past. 2001 was shot in 1968 so in a way, it tells a lot more about the year 1968 than it does the year 2001. The influence 2001 had on me is particularly visible in the white room series for instance. The white room series is even a meeting between 2001 and Mon Uncle by Jacques Tati. In general, my work is nourished by references such as Tintin or more generally master works of literature. Mostly references from my childhood. We are always the product of our own upbringing and culture.

‘Ergol #3, Arianespace, Guiana Space Center (CGS), Kourou, French Guiana, 2007.’

Engineers dressed in SCAPE (Self-Contained Atmospheric Protective Ensemble) suits inside a clean room, or a controlled environment with a low level of pollutants that’s used for activities like assembling, testing, and integrating spacecraft components and structures. Photo by Vincent Fournier

‘TS-18 chair #2, Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center (GCTC), Star City, Zvyozdny gorodok, Russia, 2007.’ This advanced chair is actually a machine used for cosmonaut selection and training, as it simulates the harmful factors of space flight. Photo by Vincent Fournier

What was your approach for “The Man Machine?”

Here I am dealing with a close future. I simply implemented robots within scenes from our everyday life—today’s everyday life. “The Man Machine” is more a parallel present than it is a future. I speculated what would happen if the robots were already part of our everyday life, at work, at home, being bored, in the streets, and so on. It also questions the identification process since these robots are humanoids. These photographs are extremely organized and composed, just like cinema is.

Would you say you are a fine art photographer?

Oh, yes! I am an artist who uses photography as his main medium. I’m not a technical photographer. The subject is always my first concern. There is a small part of naivety in my approach maybe, in the sense that there is a connection to childhood in what I do. It’s true that the starting point of my practice might have been when my grandmother took me to Palais de la Découverte [science museum in Paris] and I saw all these big machines. I became fascinated by the scientific universe, the past and the future of machines, even by the magical dimension of science.

- Photo by Elodie Daguin

- Photo by Elodie Daguin

A version of this story originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of Sixtysix with the headline “Vincent Fournier Captures the In-Between.” Subscribe today.