Michael Kupperman has been a beloved figure in comics circles for years. The New York City-based illustrator and humor writer has earned a cultishly devoted following—not to mention an Eisner Award—for absurdist characters and concepts ranging from Mark Twain’s Autobiography 1910-2010 (never mind Twain died in 1910) to Captain Marginal, which he adapted for Robert Smigel’s TV Funhouse. He also spent nearly two decades in the magazine trenches, doing instantly recognizable illustrations for The New Yorker and The New York Times.

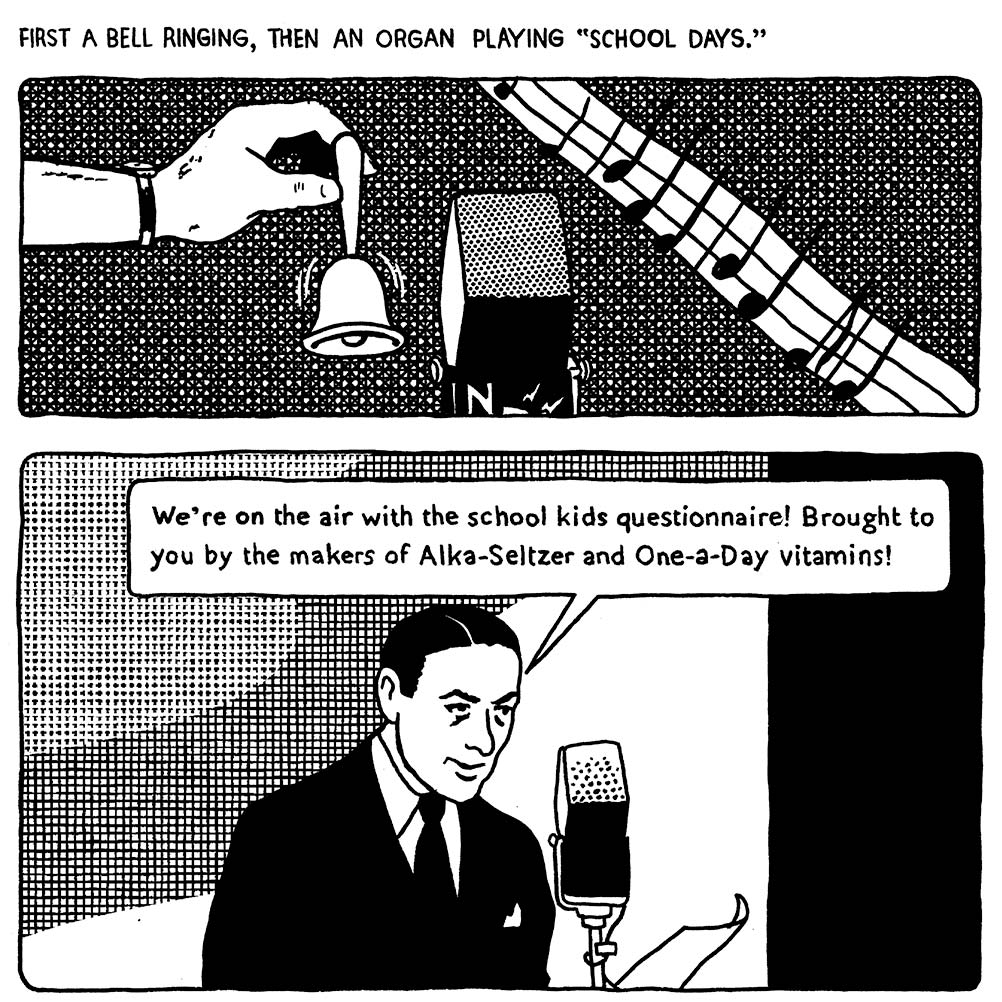

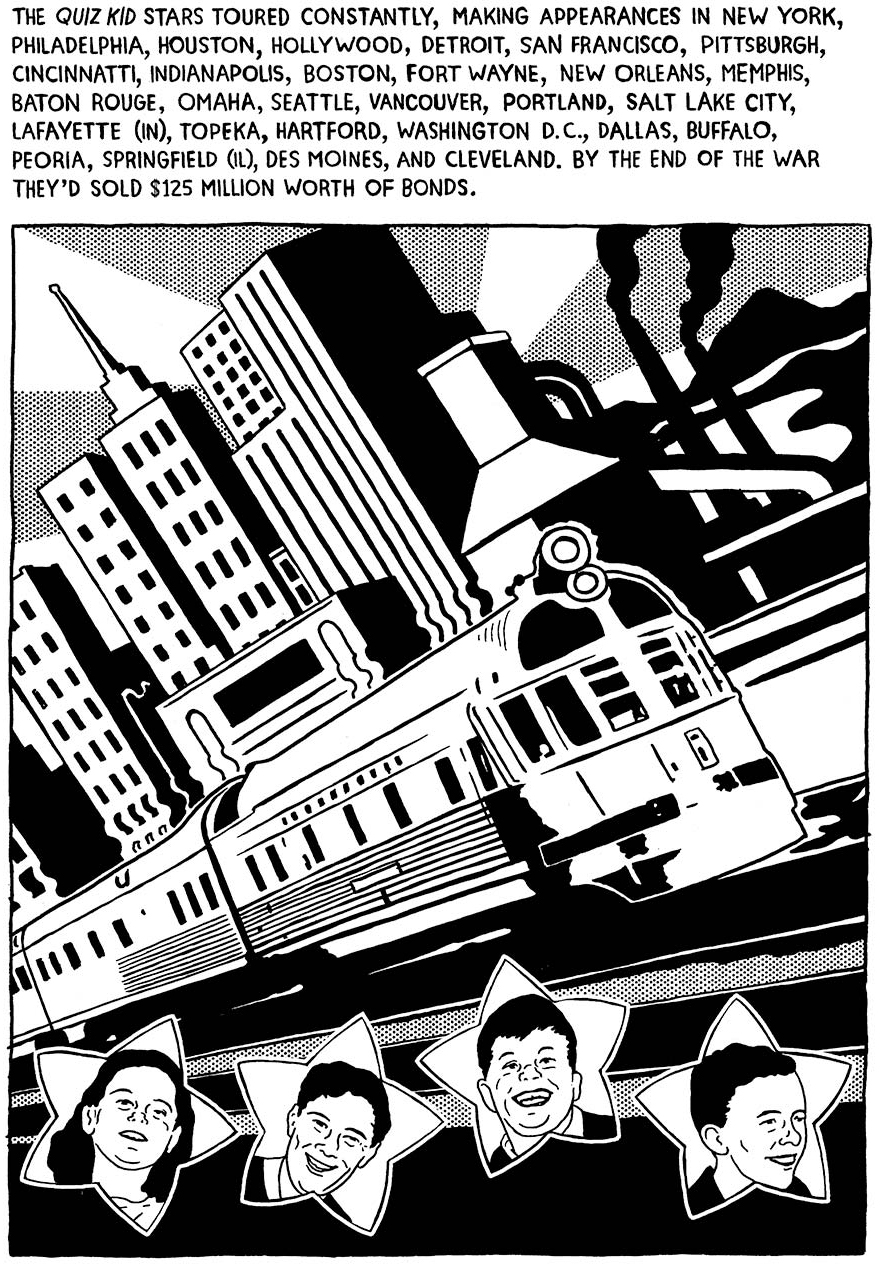

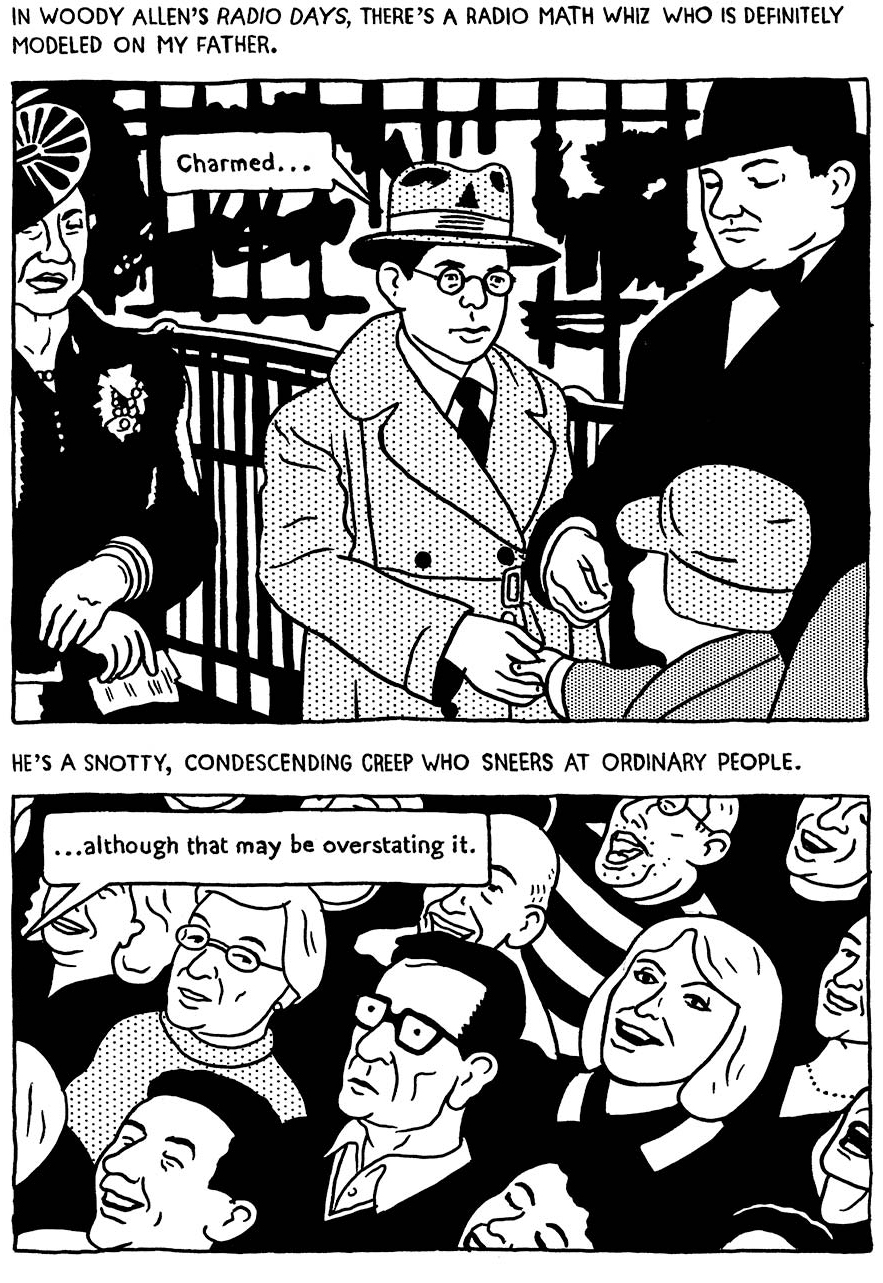

But he broke through to a larger readership with last year’s graphic memoir, All the Answers. The emotionally walloping black-and-white masterwork finds the author working through the lingering trauma that followed his father’s long streak of appearances as a child prodigy on a 1940s radio and TV trivia show—plus the anti-Semitism, detached parenting, and tolls of dementia that shade the tale. We recently talked with Michael about the dramatic tonal shift All the Answers represents, his creative process, his relationship to social media (he loves Twitter; Facebook, not so much), and more.

How did you first get into comics? Did you always want to draw professionally?

I first drifted into comics through zines. Some other artists in Williamsburg started a comic zine and asked everybody they knew to contribute. It was called Hodags and Hodaddies and it looked like something lunatics had put together, a packet of folded xeroxes in a laminated cover. One of the editors worked at Time magazine and surreptitiously put it together there at night. This was in 1989. I gradually drifted toward making comics that were a little more polished, but my first comics were improvised on the page. They were completely surreal and bizarre.

I hadn’t really wanted to draw professionally when I was younger; I’m afraid it may have been something I went into partly out of shyness.

- A panel from Michael’s acclaimed ‘All the Answers’ graphic memoir. COURTESY OF MICHAEL KUPPERMAN.

- The tone is a major departure from the absurdist, surreal mood of his previous work. COURTESY OF MICHAEL KUPPERMAN.

At what point were you able to work full-time as an illustrator/humor writer?

I decided to go for it in the early ’90s. Back then there were a lot more publications and the cost of living and doing business wasn’t so high. There were a lot of weekly papers, and I was doing about 200 illustrations a year all through the ’90s. I was doing pretty well by 2000, when the Internet bubble burst and the publishing world suffered a crash. From then on, I was working more and more and making less money. Things kept getting worse until 2008, when there was another crash—and by then the end was visible. I kept going until 2011, and since then I’ve done very few illustrations. I’d put in 19 years of work in the New Yorker and nearly that much at the Times, and then it was just over. Since then most of my income has come from comics or writing.

I know All the Answers took years to put together, and it clearly must have been a highly emotional process. What was the biggest challenge in putting it together? And was it difficult to write so nakedly about your own personal experiences?

The research was the easiest part. Then came putting it all together, and that probably was the hardest—to take my life and my father’s life and first understand them, then render them as narrative. There was the dual challenge of being truthful but also making it into a story. And I’ve read too many dishonest or partially honest books to make me want to do one myself. But, yes, as an experience it was insanely painful. Suddenly I was confronted with the invisible limitations that had governed me all my life, resulting from my upbringing.

Read more illustration and graphic novel stories at Sixtysix.

What does your drawing and writing process look like? Is there any stage you prefer over another? Do you have a set routine?

The writing comes first, certainly for the comics. It can take a long time, too. For All the Answers, I wrote it out by hand over and over. Writing by hand makes you call every word into question. As for having a set routine, I have a family so it’s really out of my power to arrange. I tend to work late at night, though, for the uninterrupted quiet.

COURTESY OF MICHAEL KUPPERMAN

Do you think readers and critics actually draw a qualitative distinction between graphic novels and comics? Has your audience changed at all since All the Answers?

I’ve been getting a variety of very interesting responses from readers about All the Answers, some of them from people who’ve never read a sequential narrative before. This is really what I hoped for. As for critics, I don’t pay too much attention to what they say.

“The future is a terrifying blur. But life is not boring.”

You’re very active—and very funny—on Twitter. What’s your relationship with social media like? Vital promotional tool? Comedy outlet? Necessary burden? All or none of the above?

I genuinely love Twitter, because it gives me an outlet for my humor and I’ve met so many interesting people because of it—sometimes even in real life. I wouldn’t say it’s done nothing for me as a promotional tool, but it’s not that great either. Facebook I find unbearable. It’s like entering a sealed room full of poison gas. I haven’t tried Instagram yet.

How important is Patreon for you?

I’ve just started with Patreon; I’m using it to try to fund my experiments in comics. So far so good.

Any comic artists or illustrators you’re particularly fond of these days? And what does the rest of 2019 have in store for you?

There are too many great artists these days to list them all, but I’ve been reading books by Gina Wynbrandt, Eleanor Davis, Julia Gfrörer, Gabrielle Bell, and Alexander Degen.

As for the future, I have no idea. The future is a terrifying blur. But life is not boring.

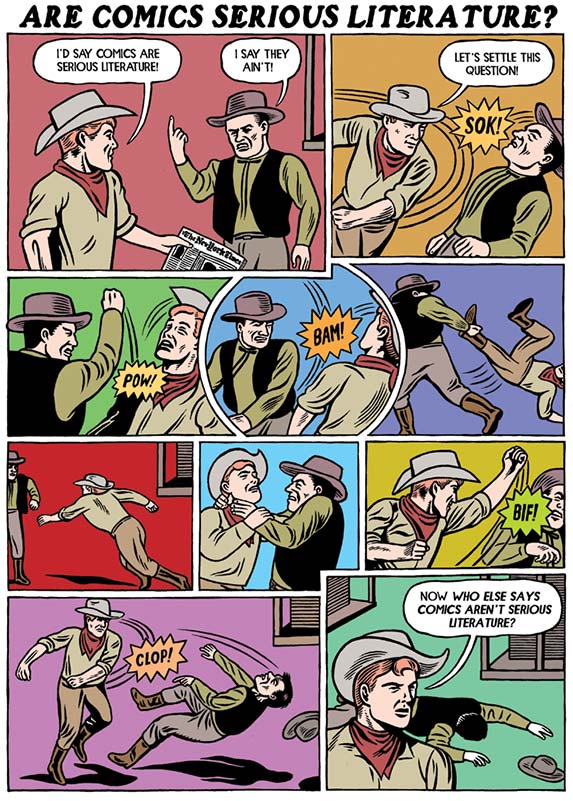

An earlier Kupperman comic with some clear perspective on the perceived graphic novels vs. comics hierarchy. COURTESY OF MICHAEL KUPPERMAN.