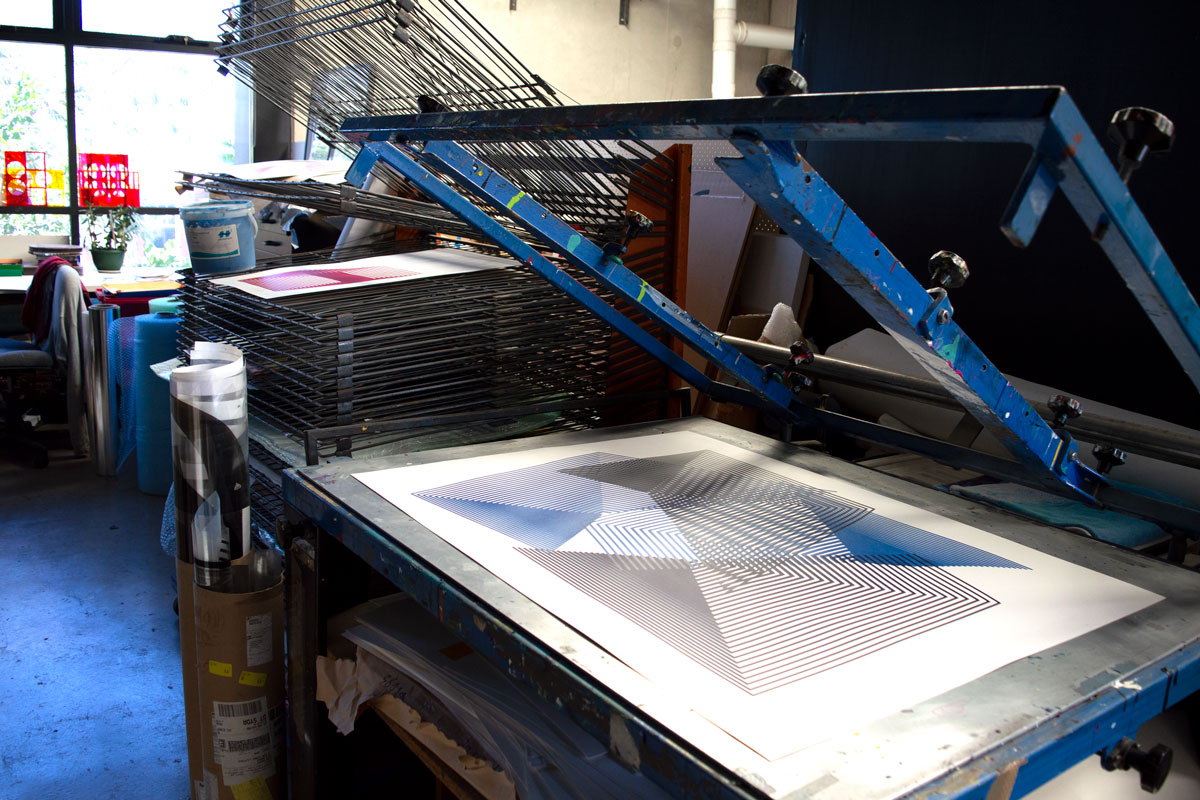

“So, what you’re telling me is you don’t know what you like, or why you like it, you just know what you like when you see it?” This, hurled at me by an overeducated, under-successful graduate school art professor, hit me dead between my eyes. “Um, yeah,” I replied. My theory improved, my tongue sharpened, my skin thickened, but grad school was not for me. To this day I frequently like—love even—the works of artists and designers without always understanding why I’m attracted to them. Sometimes you just get a feeling about someone’s work, or process, and you give it a little more patience than you normally would—and your admiration develops. It’s difficult to ignore work that is the product of brutal, intensive labor, crafted by hand during hours of introspective and isolated studio time. Without knowing Kate Banazi, but just by looking at her work, I knew she’d check these boxes. You know it when you see it. Despite maintaining a meticulous and demanding studio practice, Kate believes in embracing the accidents that come from screen printing. Rather than touch up minor imperfections in her prints, the London-born, Sydney-based illustrator and printmaker prefers to let the flaws be. The process, patiently layering screen after screen to create an image, reveals her intent, a harmonious kind of beauty, where geometry, color, light, and layers complement each other.

Kate, who comes from design stock, has designed prints for the likes of fashion designer Dion Lee, Australian bra brand Berlei, and—for a circular jigsaw puzzle—artist agency The Jacky Winter Group while exhibiting her work around the world. I recently chatted with Kate, who also creates paintings and textile art in addition to prints, from her studio in Australia. We spoke about refining your creative voice halfway around the world from home, the increasingly porous line between fine and commercial art, and the infinite well of inspiration that is Serena Williams, who sported one of her prints on a sports bra in the Berlei campaign.

I’m in Chicago. For some reason I thought I was going to find you while you were in London. I didn’t know I’d be catching you in Australia so early in the morning. Are you always up this early?

I’m quite regimented actually. But it’s good as well, isn’t it? To have these kind of regimented basics in your artwork. It helps you learn a different process. It’s like doing accounting sometimes.

Is your background more in the arts or more on the design side?

A bit of both, really. It’s really more design. I started in design, in fashion. My parents are in graphics and typography.

Was your first real job in the fashion world?

Oh, no. I guess my first real job was cleaning bathrooms. But in the design world, yes, retail and fashion. My family always loved fashion as well. I’ve got an older half-sister who’s in the fashion industry, so that was a big influence. I love fashion. When I came out of college, it was definitely more about fashion. We were taught to research. It’s a much slower pace so, in that respect, art came into the fashion more, rather than the other way around. The practice was, well, creative is not the right word, but fashion was slower. You can bring all those different elements together and consider them; it wasn’t 20 collections a year, but more about taking time. Sketchbooks and all of the visual diaries were very important to me.

At what point did you leave fashion and transition to your own studio practice full-time?

It was when I moved to Australia and I had nothing here. That would have been the first time I had my own kind of practice where there was no fashion, there was no other thing. Things were going on in the background for work, but it was primarily a lot of, “Well, OK, what am I going to do?”

What brought you to Australia?

I fell in love.

That’s a great reason.

Country and man. He was based here. We spent time in London together and then we thought we’d try here. The sunshine helps. Beautiful country here as well. Incredible people.

I’ve never been to Australia. I feel kind of ashamed that I’ve never been. I feel like it’s a place I should have visited at this point in my life.

Really? I didn’t know. It’s one of those places that’s so vast and huge, but people don’t think about it. It’s really strange. I never felt the urge to go; and then, suddenly, I did.

- The Topographic Bloom jumpsuit, featuring Kate’s signature artwork for The Social Outfit; $369

- “Cryptic Colouration 1,” hand-printed silkscreen print on 360gsm Italian-made, forestry-certified, acid-free paper with hand-trimmed edges, 2018

When you first arrived in Australia were you concerned about starting an economically viable career, or were you moving under the comforts of knowing you’d have a runway to figure things out?

Oh, no. I definitely had the comforts. I had my practice, and it was quiet, and it was my own. The groundwork was all there. It was just a matter of finding my feet and my headspace. My partner was just like, “Take your time.” He really understood. You know, I was isolated, so he was very supportive of me finding time and space to locate my voice here.

That was very interesting, being away from the place where you grew up. You find yourself. There are no other people’s influences of, “Oh, you’re not like that. That’s not what you do.” Suddenly you go, “Actually, I really love this.” That’s a benefit to moving so far away from somewhere familiar; you’re allowed to blossom if you allow it.

Kate was invited by Australian lingerie company Berlei to create a special artist edition of their classic bra to celebrate their centenary. She created four prints, one of which was modeled by Serena Williams.

Were you doing some commercial work at this point?

Always. Still do. I have to. I love it as well. There’s no denying that because I think it feeds both things. I think the crossover of what I learn in both sides feeds both sides.

I’ve just done a brief for a food company and some proposals for an internet company. When you work for someone like Berlei, who makes bras, or Nike, you’re basically coloring in. You get these really hard and fast briefs and timelines; it makes you a bit more agile, doesn’t it? It makes you think on the fly and think differently. So when I take that into my studio, I can work faster.

By contrast my studio practice becomes quite indulgent. But you have to be pragmatic about paying the bills. Plus, I like working with people. If I’m sucked away in a studio, I don’t get to meet anybody. I just end up dribbling, kind of just losing all social skills. It gets embarrassing, to be honest.

Is it fair to say clients who come to you think of you largely as an illustrator and ask you to spec ideas for projects?

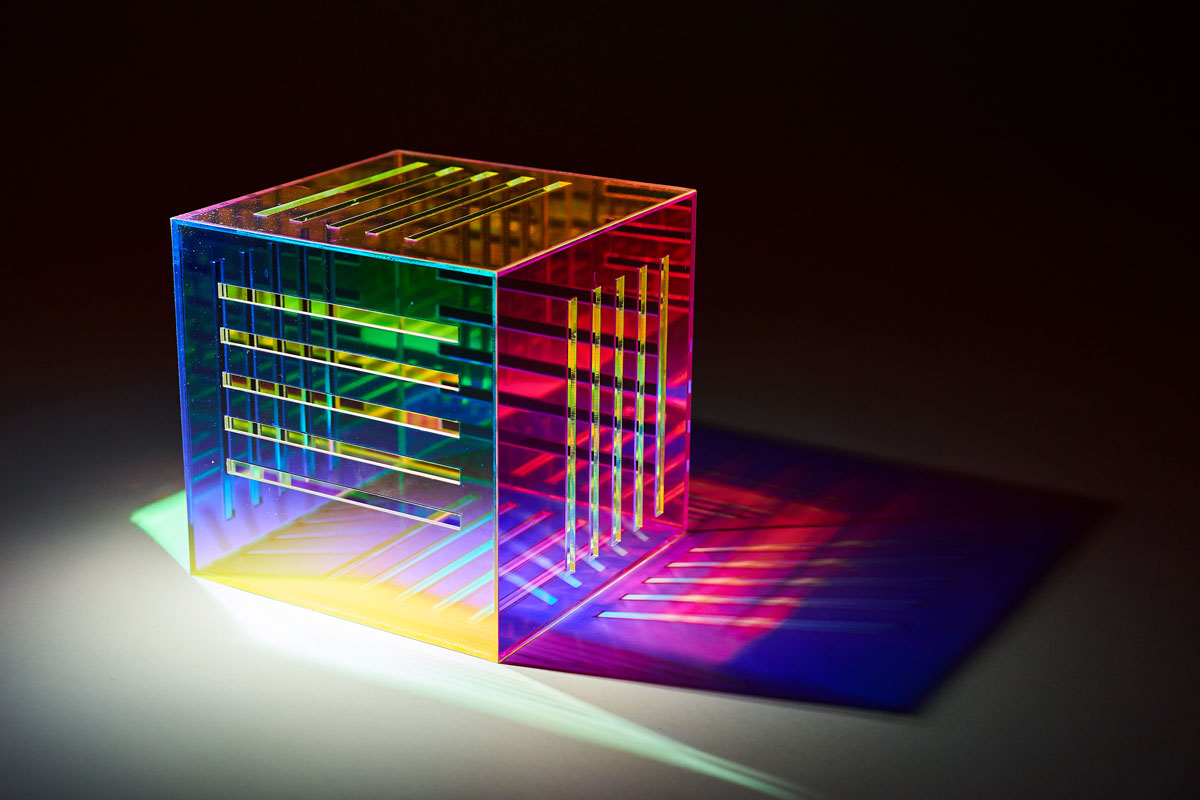

It’s becoming closer and closer between pattern-making and decorative work, work that’s less illustrative with a narrative, and more work that packs a punch with a pattern that has an idea or research behind it.

People understand my work more and more, or see different things in it, which is always interesting as well. So it’s becoming less about a straightforward illustration job. I get to work with people because they see the merit and the visual. That’s all I can really say, rather than having to say, “OK, well, we want you to illustrate this story,” which I still do every now and then as well to keep my brain ticking, but I’ve got to say that is really not my forte. When I see my friends who are professional illustrators able to be clever and quick on the narrative and make it visual, I can’t do that.

Related | Death Spray Custom is Making Racing Fun Again

For the art-based practice, I have my set prices; it’s done and that’s it, so I know that. But in the commercial world things are becoming more expansive. I did this amazing light show where I got to work with a guy who programs lights on a massive scale for shopping centers and things like that. There are those sorts of things that are happening now and I have an illustration agent who manages all that. He’s the one who’s able to say, “They came with this budget. I think it’s worth this. Are you happy with that?” So, cost-wise, I don’t really deal with any of that, he does.

Now, more and more projects are these amazing things where you get to play with other people’s toys, and I have to say I’m greedy for those experiences. To be able to watch someone who’s really good at what they do is really inspiring; it really gives you something to take to your own practice. And although it’s a completely different field, you can see how you can apply it to learning more on your own, or being brave, or trying something without worrying about failure. I think that’s a nice thing about trying different stuff, especially if you’re playing with someone who is guiding you and you have no experience in that. There’s no going wrong, is there?

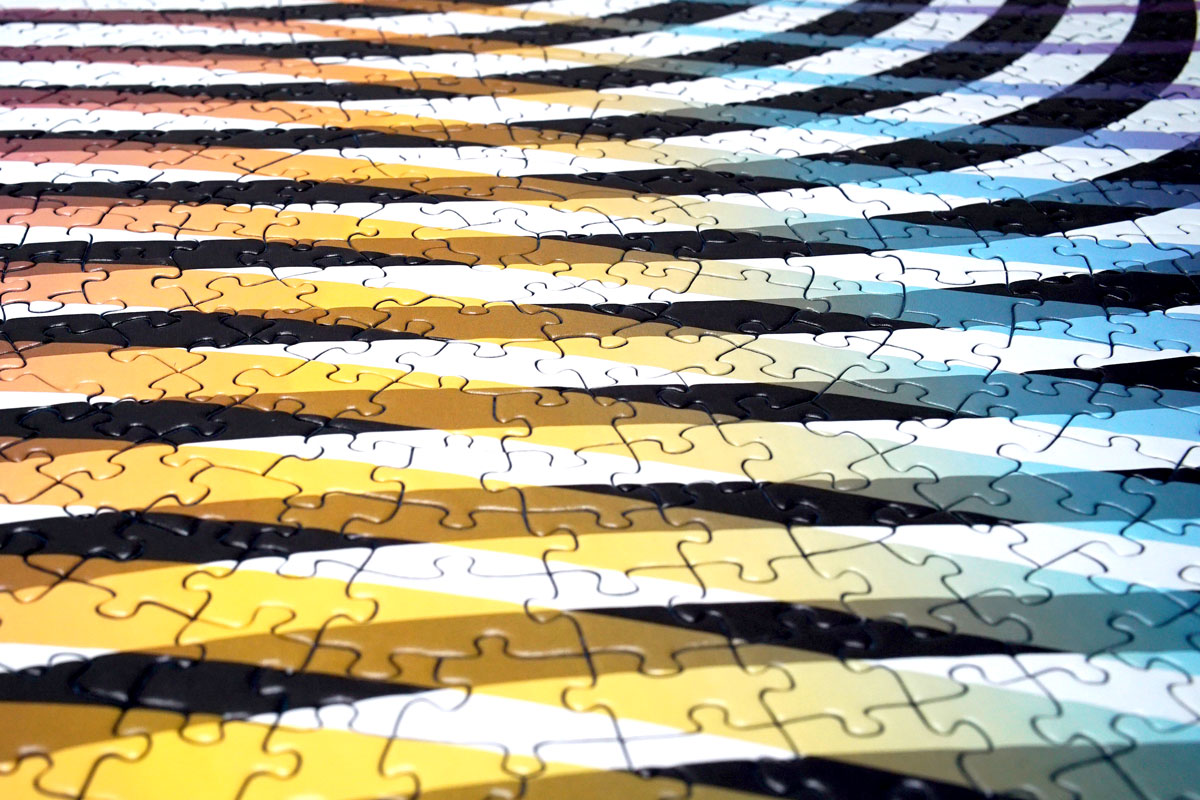

Kate designed a 1,000-piece puzzle with Karen Singh and Marc Martin. The puzzle comes in an octagonal box as part of a series of circular puzzles created by The Jacky Winter Group.

I remember the first time I worked with a great art director. He’d look at our page studies with this confidence and artistic seriousness. I’d never really witnessed someone treat design that way before. It’s not so much what I learned from working with him as far as what he put on the page, but it was the way he handled himself in thinking of the work. It changed my own practice and what I was doing, seeing how other people think of their own work.

Yeah, you’re right. And also, they can really give you a validation of your own work, can’t they? Very quietly and very carefully. I really admire that as well when you get a good art director who can very much guide you but let you do your own thing. And then, you realize what a good art director he is. They can be so inspiring. It’s such a rewarding experience to have that quiet guidance.

Could you talk about some of your most interesting experiences bringing your prints off of the printed page?

It’s usually a collaborative process and I used to do that with my textile work in London. When I got to Australia I worked with Dion Lee, the fashion designer. That was an amazing experience for me because I was doing very flat, very linear artwork at that point, and he put them onto his clothing; he embossed them, debossed them, sliced them up. And that just changed everything because I presumed it was going in another direction. He said to me, “Are you happy for me just to do my thing on it?” And I was like, “Yeah, absolutely!” It was so unexpected, and it opened my eyes up to seeing my work in a different way. Having that interpretation and that faith in someone else’s work is important to me.

- Kate describes her studio in an old factory in Sydney as “borderline feral.”

- Rather than focusing on a narrative, Kate embraces the versatile meanings of her illustrations.

What was it like seeing your work worn by Serena Williams?

I have to say I had a little cry. She’s such an icon for me. She is an inspiration and a powerhouse and an incredible woman. That’s aspirational for me to have that tenacity.

Being shy is a very difficult position to be in. There are so many people making art and doing things, you have to be quite boastful. I’m still learning to do that and I’m nearly 50. Seeing Serena Williams in my work, yeah, I feel a bit safer now, to be honest. I can have a little bit more faith in my own work. And also I can help others have a little bit more faith in their work.

There’s something very natural about your collaborations versus, say, seeing Chance the Rapper doing a Mountain Dew commercial. Your partnerships always seem to make sense.

Those are really kind words, thank you. I think maybe I don’t sit in the fine art world as well. The fine art world can cross over into the design world. It’s like there can be a collaboration and I’ll put it under the term of collaboration of a fine artist moving into a design project. So working for an athletic wear brand or Apple or whatever. That’s fine, but for a designer to cross into the fine art world—that’s still a bit of a no-no. It’s not taking it seriously. I’ve had legit conversations with people who are in the fine art world saying it’s such a shame you do commercial work because you’d be taken a lot more seriously if you were working, say, as a waitress. I don’t get that at all. I don’t understand that because why would I not be practicing my craft or my trade every day if I possibly could, rather than doing something that is not related?

I’ve watched so many of my friends struggling doing art, and purely their art. The rigor behind it is the same as we’d apply to a design process, so why should they have to struggle just because it’s deemed inappropriate from external forces?

There’s an argument though that not all fine art translates to the commercial world in a positive way.

No, true. I agree with that. But I still think the crossover is coming and it needs to happen a bit more so everybody can benefit in some ways.

I think the fine art world is bending to be a bit more like the design world, understanding that those collaborations have lots of benefits. Lowering the level of suffering is a good long-term strategy.

Good work comes out of suffering, but good work comes out of being safe as well.

Photos courtesy of Kate Banazi.

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of Sixtysix with the headline “Suffering and Screen Prints with Kate Banazi.” Subscribe today.