“What if we could enable others to see bacteria as a carrier of meaning, rather than a carrier of disease?” asks Stockholm-based designer Jan Klingler. For this year’s Stockholm Furniture and Light Fair, Jan exhibited a collection of Bacteria Lamps in the Greenhouse section, the Young Swedish Design exhibition hall dedicated to independent designers and design schools.

Devised from bacteria cultures grown on resin plates, Jan decorates each uniquely formed dish with an LED lamp that can either hang on a wall or rest on a table. Reminiscent of a laboratory experiment, the result is a cross between art, science, and industrial design—where a bacterial swab taken from a loved one, pet, place, or building becomes the seed for a custom light. In speaking with Jan, we learned more about his process and whether he thinks his designs can shift the negative connotations around bacteria and bring the concept into mainstream design.

Jan exhibited his Bacteria Lamps at this year’s Stockholm Furniture and Light Fair. COURTESY OF TRENDNOMAD.

What drew you toward working in design?

I think that many of us experienced a very stressful time after graduating from high school. Feeling the pressure of making one’s first decision that’s not a given but actively made by oneself can be very paralyzing. At that point, I was very torn between studying medicine, biology, or something in the creative field. With my mum being a graphic designer, I knew there were many different possibilities in design, and I decided to give myself the opportunity to explore them during a year of general design at the University of Strasbourg in France. It was then that I fell in love with industrial design and decided to pursue and concentrate on this path when I went back to Germany.

Where do you find inspiration?

I enjoy finding design inspiration in the most unexpected of places. I would describe myself as a rather extroverted person who loves to learn about many things outside of my personal comfort zone as a designer—such as microbiology. I think these interdisciplinary conversations and constant new experiences are vast sources of inspiration for my creations.

Jan’s Bacteria Lamps wed industrial design and microbiology. PHOTOGRAPHY BY SANDY HAGGART.

Run us through the inspiration for the Bacteria Lamp project and how you first conceived the idea.

The design process of my work exhibited at the Greenhouse this year is the result of a search for purpose and meaning in my creative work. During my master’s study at Konstfack, I investigated how to create strong and long-lasting relationships between my creations and their new owners. My starting point was to look at my own personal belongings first. Having moved across borders five times during my studies, they had been reduced to an all-time minimum. Next to the core necessities of things like clothing, there were also quite a few oddities. For example, a wooden chess set that had no apparent purpose, as I did not play chess and did not have a strong urge to learn it, or an aftershave that I was not able to use as it made my skin itch in an allergic reaction.

Yet I chose to take these things with me wherever I went. But why? It’s the story behind these objects that made them so important to me. Both of these objects were inherited and carried memories of very special people who are no longer with us. When I looked at the chess set, I thought of my great-grandmother—a strong, opinionated woman with a big heart. When I smelled the aftershave, I immediately had flashbacks to happy moments with my grandfather during my childhood.

“The possibilities are as individual as each one of us.”

The work presented at the Greenhouse is the result of my research on how to give new objects the opportunity to be vessels of past memories and give them a deeper relationship with their owner. We all consist of 10 times more bacteria than human cells. Every living being and place has its own unique and personal microbiological fingerprint. So with the Bacteria Lamp, samples are taken from people, places, or things that hold a position of importance, and are grown into a unique piece in the form of commissioned work. Whether it’s the location of a first date, a personal souvenir from a memorable journey, or the reminder of a loved one far away, the possibilities are as individual as each one of us.

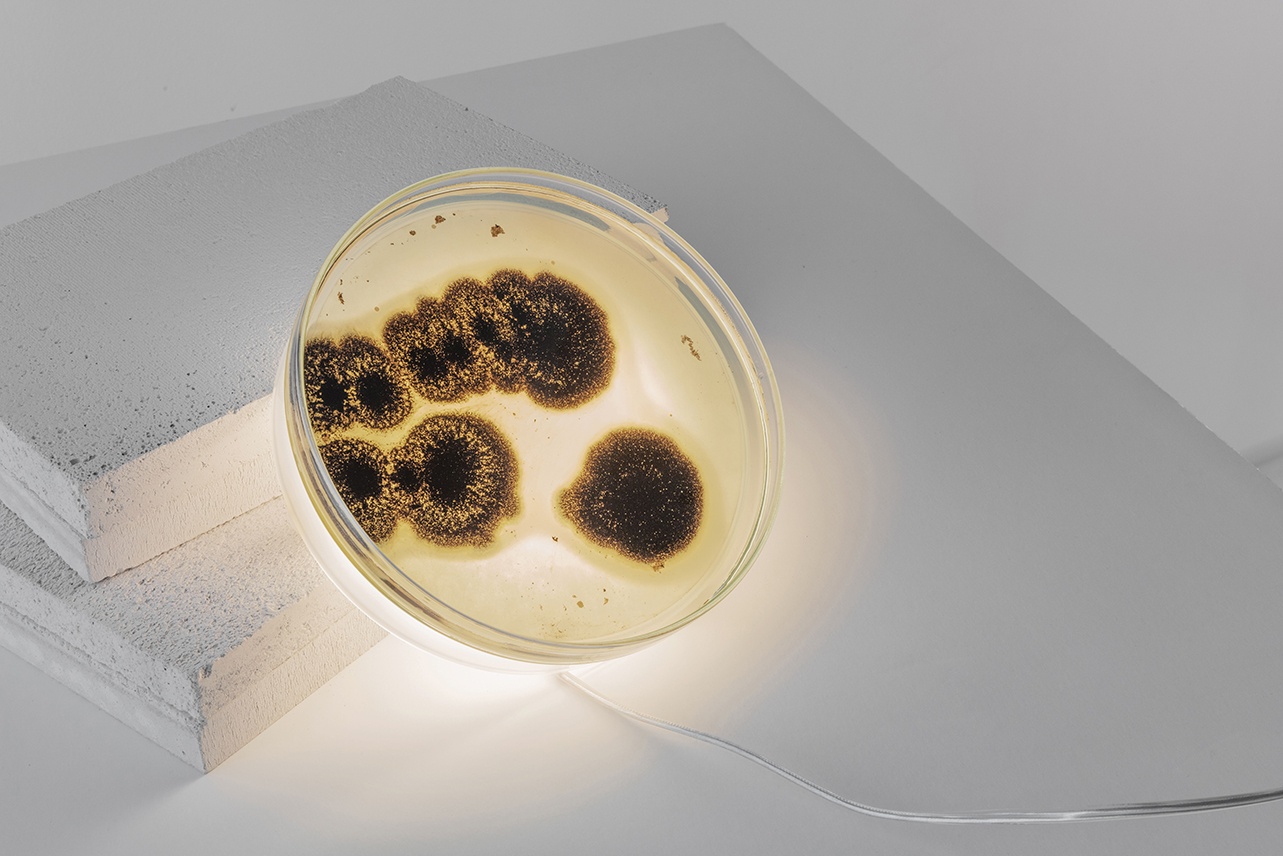

The Candida Krusei + Candida Glabrata Bacteria Lamp by Jan Klingler. PHOTOGRAPHY BY SANDY HAGGART.

How do you create these beautiful patterns? Are they each unique and random, or is there some kind of controlled method?

As an industrial designer, I am used to planning and defining my designs very carefully and precisely. It’s for this reason that I love to work with these microorganisms so much. In this successful marriage between art, design, and science, they definitely take the role of the artist, surprising me every time with their growth patterns, which turn out very differently from what I imagine when planting them. The colors are dependent on the species of the microorganism, as well as their nourishment ground. Most often I have grown probes from places and people in smaller Petri dishes first and selected one or two colors that are then multiplied in the final vessels. When producing a piece for commissioned work, the customer is very much involved in this process, getting to choose between the colors that grow or having a pure mix of all of them.

Read more industrial design stories at SixtySix.

After a growth period of 24 to 48 hours, the microorganisms are fully sealed within resin to stop the growth and to preserve them for eternity. An LED light source incorporated into a custom silicone plug highlights the visual quality of the growth pattern and colors from above or below.

The Aspergillus Niger Bacteria Lamp by Jan Klingler. PHOTOGRAPHY BY SANDY HAGGART.

Can you run us through some of the lamps you’ve designed so far? Are there any stories you can share?

The one with the strongest personal emotional value is taken from a column in Östermalmstorg, the place where I first met my boyfriend. As an abstract reminder of the start of our relationship, it was fascinating to see how my partner bonded strongly with this lamp like I envisioned happening. Other pieces were grown out of samples from friends and landmarks of the city. I think that everyone leaving their home for a specific reason—whether it be studying, a new job, or love—feels the need to bring a piece of the old home with them. This is why I am planning to take probes of mine and my partner’s families as soon as we see them next time.

Jan’s stand at this year’s Stockholm Furniture and Light Fair. PHOTOGRAPHY BY PIOTR SKRZYCKI FOR MINISTRYOFIMAGES.

The general perception of bacteria is quite a negative one, linked heavily with disease and ill hygiene. How do you plan to shift these connotations with the Bacteria Lamps?

I would like to change the perception of bacteria being a carrier of disease to being a carrier of meaning. We live in a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. In recent years the public is becoming more and more aware of it, even though the popular focus is currently on the bacteria of the gut. But we have bacteria everywhere, and for each and every one of us, it is unique and personal—like a microbiological fingerprint. But of course, the fear of the invisible still persists in many of us. I hope visualizing bacteria in the way my lamps do will take a lot of the fear of the invisible away and let people see the beauty and importance of our microorganisms.