The Rolling Stones continue to defy the passage of time. Their latest tour, Hackney Diamonds, proves yet again why they’re considered rock ‘n’ roll legends. For this tour, the band’s larger-than-life stage presence is matched by equally stunning set designs led by masterminds Ray Winkler and Patrick Woodroffe. With decades of experience in their respective fields, Ray and Patrick have become synonymous with the visual spectacle that defines a Rolling Stones concert. Their collaborative work has transformed stadiums into dynamic, immersive experiences that are as much a part of The Stones’ allure as Mick Jagger’s swaggering moves or Keith Richards’ legendary riffs.

Ray Winkler, the CEO and design director of Stufish Entertainment Architects, has created groundbreaking stage designs for some of the biggest names in music. Ray’s architectural background and his innovative approach to entertainment design have made him a sought-after figure in the world of live entertainment. Stufish, known for crafting the stages for artists like U2, Beyoncé, and Madonna, has been a frequent collaborator with the Rolling Stones since the early 2000s.

Patrick Woodroffe, the founder of Woodroffe Bassett Design, is a lighting designer whose work has illuminated some of the most iconic concerts of the past decades. Patrick’s career spans over 40 years, during which he has worked with artists ranging from Michael Jackson to Adele. His knack for transforming lighting into an art form has made him an indispensable part of the Rolling Stones’ touring machine.

The Hackney Diamonds tour is a carefully choreographed fusion of sound, light, and architecture. After seeing the show in Chicago I spoke with Ray and Patrick separately to share insights into their creative process, the challenges of designing for a band as iconic as the Rolling Stones, and the unique synergy that has made their collaboration a success.

The Rolling Stones Hackney Diamonds tour is a carefully choreographed fusion of sound, light, and architecture.

Chris Force: Your professional experience in architecture is vast and impressive, how did you get your start?

Ray Winkler: I was pretty useless at everything else, so I decided that architecture was really what I wanted to do. I started my education in design as a furniture maker. For three years, I made furniture, everything from felling a tree to cleaning a piece of wood to building a chair.

This gave me a very good practical understanding of design and the correlation between materials and the process. Once I did that, I decided I’d like to study architecture. I enrolled, and to my great delight, I got an offer from one of the schools in London called The Bartlett School of Architecture, which is part of University College London. Then I got a scholarship to go to SCI-Arc in Los Angeles for my postgraduate studies, which I did.

In Los Angeles, I got a flavor for ephemeral architecture, meaning architecture that is very light in its touch and doesn’t require the permanence that many buildings have. I was influenced by the architectural movement in the 1960s, Archigram.

A professor at the school at the time, Peter Cook, and Mark Fisher, who was the founder of Mark Fisher Studio and later co-founded Stufish with me, were proponents of this type of architecture. They saw it as a blend of pop culture and architecture, thinking about things very differently. Touring architecture fits nicely into that hybrid of being very architectural in its intent but very fleeting in its presence. Our sets sit on a site for about a month and then disappear, never to be seen again.

When you started university, you’d been working in furniture design, building functional objects. Did that impact your formative years in architecture in any way?

Ray Winkler: Yes, very much so. Architecture can veer into the hypothetical, but when you design and build furniture, you must ensure its fit for purpose. I learned everything from felling a tree to cutting it up, to designing the furniture, and selling it. This gave me a different perspective on the requirements and obligations of a designer. It’s about creating something that’s pleasing to the eye, touch, and comfort of the user.

This practical understanding translates into architecture, where the technology is secondary to the purpose of the design. Whether it’s a piece of furniture or a set, it needs to work, be built, performed on, and taken down while maintaining its design integrity and meeting budgetary and emotive ambitions.

When was the first time you met Mark Fisher?

Ray Winkler: I first met Mark Fisher in 1992 or 1993. Throughout my college years I worked with a company called Atelier One, which specialized in lightweight engineering. They were Mark’s chosen engineering company because they understood the requirements of ephemeral architecture, where weight, speed of assembly, and efficiency in packing were crucial. I was very involved in that thinking from an engineering perspective early in my career. I started architecture school in 1990 and began working for Atelier One almost immediately after. I met Mark casually through interactions and never thought I’d work with him until he became my external assessor at The Bartlett. He was tough and didn’t like my work initially, but later offered me a job.

Thirty years later, I’m still here, so I must have done something right—or terribly wrong, to still be here.

“All the shows we do work within the same economic, structural, and logistical constraints,” says Ray Winkler. “But we’ve always been of the mindset that you rephrase a problem as an opportunity to think about it differently.”

Was he always tough?

Ray Winkler: He was a great guy with an incredible intellect and a broad understanding of the subject matter beyond just architecture. He was very private, but once you got to know him, he was incredibly generous with his time and effort. I owe a lot to him. We were a small team at the time, just three people. I learned a lot from sitting in the same room, overhearing every conversation, and participating in every discussion. It was tough but he was fair in his approach.

Was there anything that distills down simply that you could share as a key takeaway from your collaboration with him over the years?

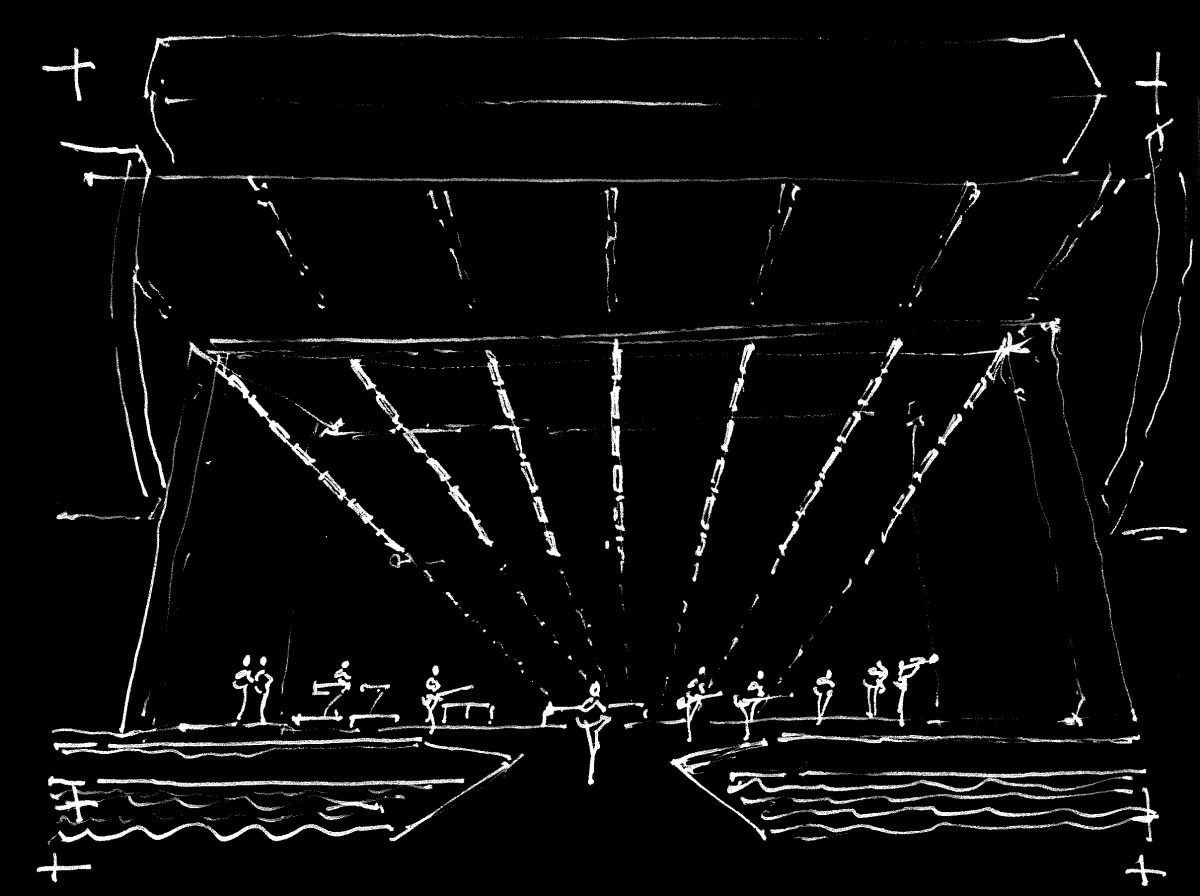

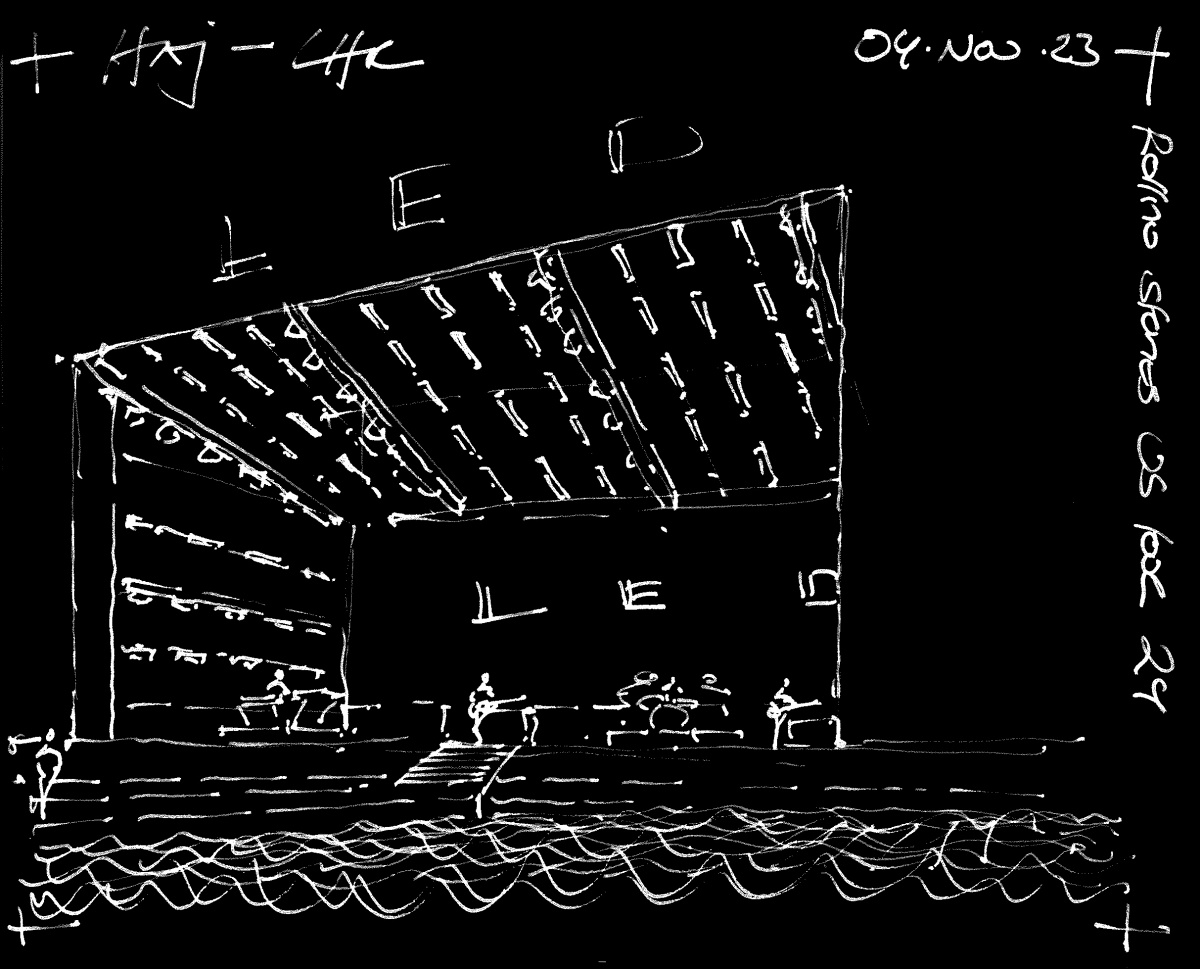

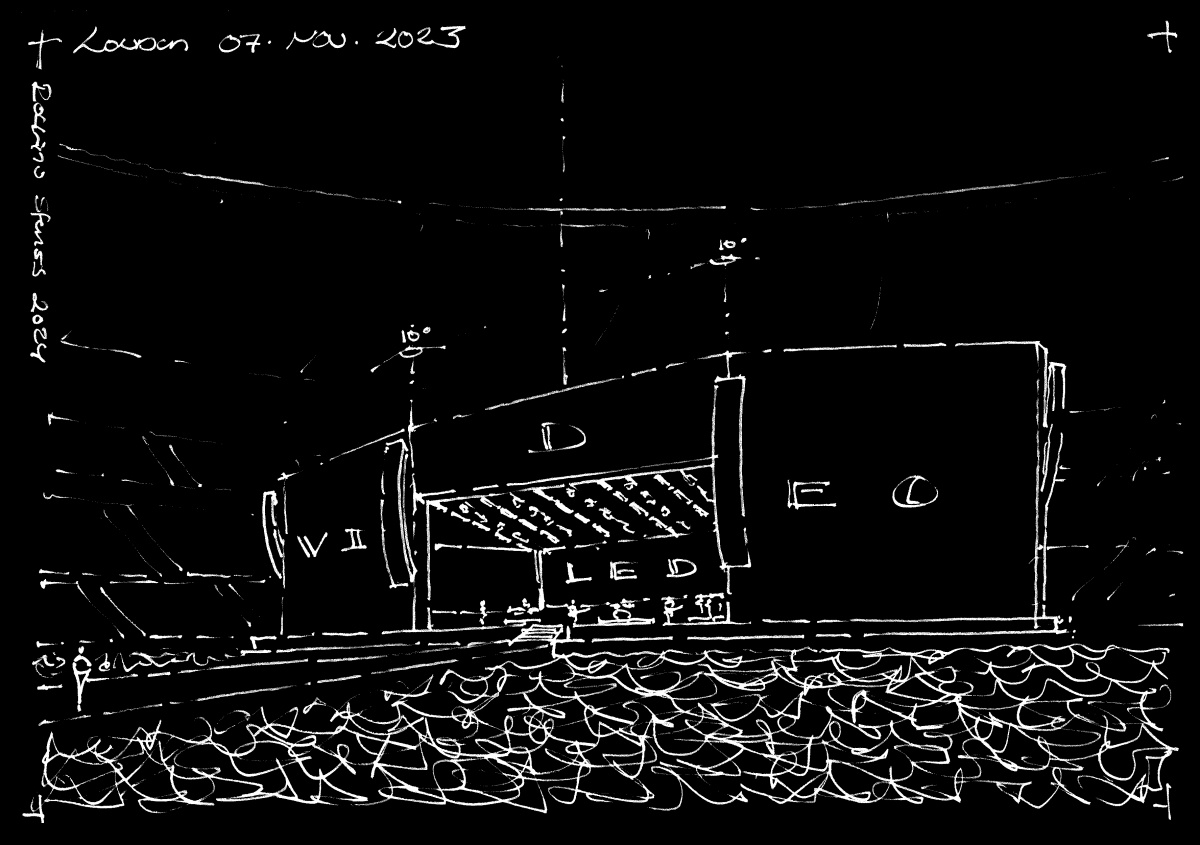

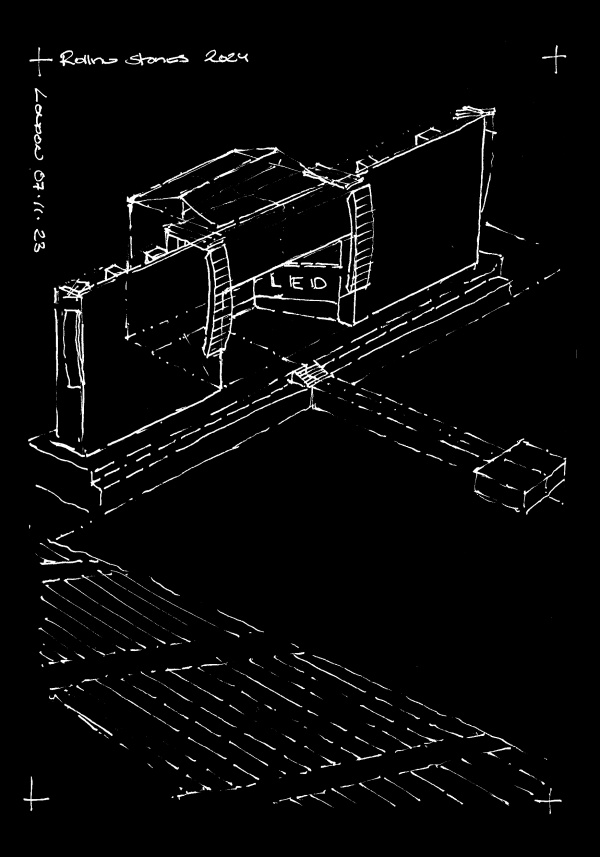

Ray Winkler: I learned that the art of drawing is essential. I don’t know what I’m thinking until I’ve drawn it. Mark emphasized putting ideas on paper quickly to ensure everyone is on the same page. It allows you to verify that what you think the client wants is actually what they want.

Another important lesson is not to draw things that you can’t be built. The stuff we do needs to be delivered on the promises we make. This is why we’ve had long-term clients like the Rolling Stones since 1989, U2 since 1992. It’s about balancing creativity with practicality and ensuring ideas are realized, not just hypothetical. Ideas should be measured by their realization, not just their proposition.

If we as architects can’t deliver a design we won’t be hired the next time because failure is measured in very clear financial terms. It might be critically acclaimed, but if they’re not selling tickets, if it’s too cumbersome to travel from A to B, it’s meaningless. It sort of is stuck in the realm of ideas that never really made it because they have no chance of surviving in the real world.

“Mark Fisher emphasized putting ideas on paper quickly to ensure everyone is on the same page,” Ray says. “It allows you to verify that what you think the client wants is actually what they want.”

It’s got to work. It’s a chair you have to be able to sit on.

I’ve heard you say, “Just because you have a bowl of sugar doesn’t mean you should put all of it into the coffee.” I think you were referencing technology and how to balance want to throw at a performance when you have someone as epic as the Stones taking the stage. I’m wondering how you consider restraint in the design phase?

Ray Winkler: Show business is our business. We approach pretty much every project with the same sort of professional attitude. As architects, we’re first and foremost trained to solve problems in the 3D spatial world, and very specific problems that are to do with the entertainment world or creating a “wow” factor—the spectacle that differentiates this show from another show and makes it quintessentially Rolling Stones rather than a Beyoncé or a Queen show.

All the shows we do work within the same economic, structural, and logistical constraints. It doesn’t matter who goes out at what time; they pretty much will go into the same arenas. But we’ve always been of the mindset that you rephrase a problem as an opportunity to think about it differently.

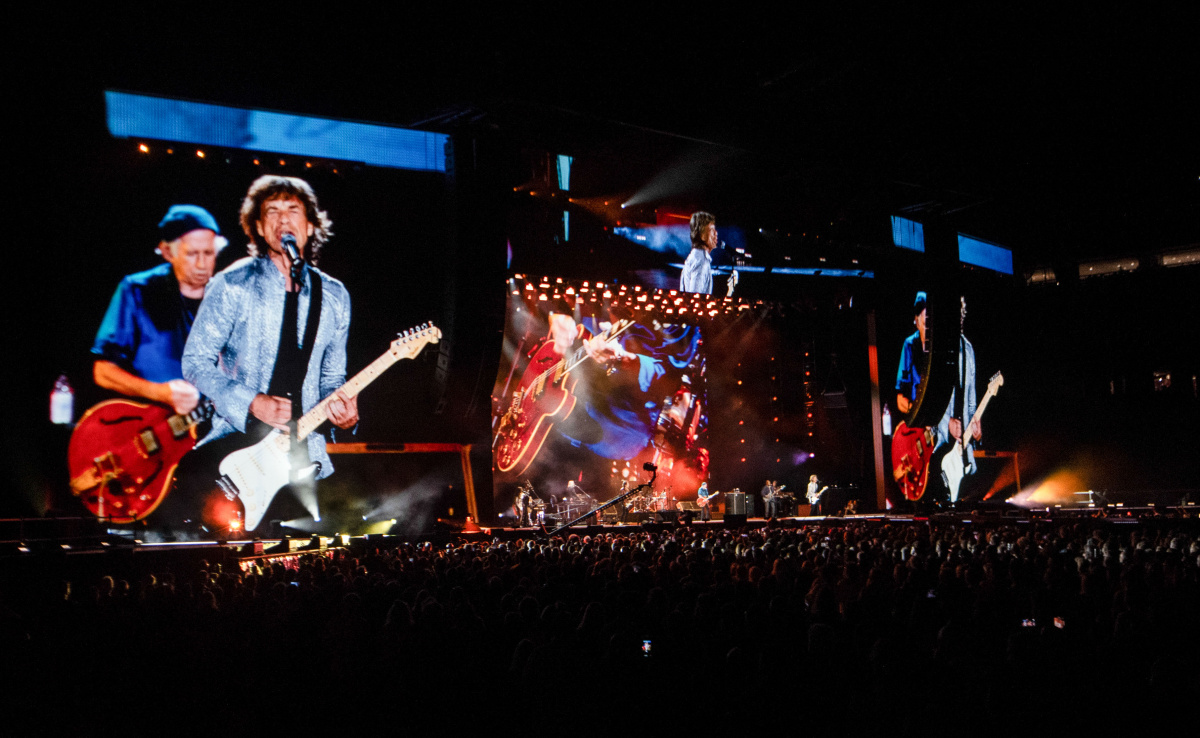

The problem we had was that shows were getting bigger and audiences were getting further removed from the very reason why they’ve come to the show—to see their artists. We had to create technology that would allow us not only to see the artist on the big screen image magnification, but also weave a digital narrative around the performance that was tailor-made to the performance.

- “The problem we had was that shows were getting bigger and audiences were getting further removed from the very reason why they’ve come to the show—to see their artists,” Ray says. “We had to create technology that would allow us to see the artist on the big screen.”

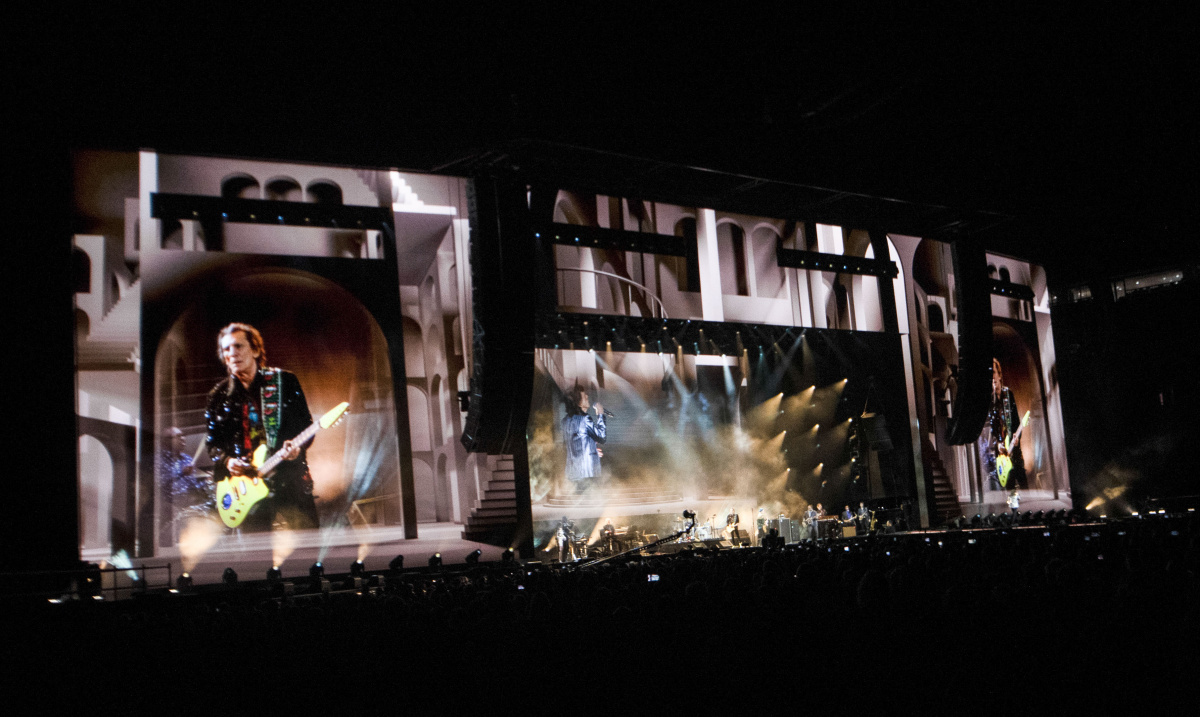

When it came to designing [The Hackney Diamonds tour] for the Stones, we had the great privilege of saying, okay, the technology is very well established. It now tours incredibly efficiently. We have a band that is incredibly progressive, that after 66 years of being a band, still managed to create an incredible album and hit the charts, right? You’ve got the ingredients of a perfect storm.

What was clear to us is that the Stones had never gone entirely digital before. They still are, at least musically, very much rooted in the analog world. They were willing to take that break and say, “Okay, what haven’t we done before?” They’ve worked with Andy Warhol. They had Jeff Koons on the Licks tour. We’ve worked with so many great visual artists, but we’ve never really worked entirely digitally within the framework of a big video screen.

“The art of drawing is essential. I don’t know what I’m thinking until I’ve drawn it.”

—Ray Winkler

The architectural conceit was actually a very simple one: Find a language and a building block that allows itself to take control over the meta-architecture that is the construction of a very box-like structure, which is very boring. Treat it in a way that once you switch the lights off and the video fires up, you can transport the band and the audience into so many different directions.

The thing to avoid here is that one can become lazy very quickly and say, “Well, don’t worry about the construction of the house. We’ll wallpaper across all of the gaps, and the wallpaper will be so fabulously bright and beautiful that nobody will notice.” You have to have a good reason to employ the technology in the first place so you don’t run the risk of becoming subservient to it. My analogy with the cup of coffee essentially asks: why add another spoonful of sugar, when all you end up with is something that does not taste anything like what you set out to do in the first place?

- The set turns black and white and “punky” during “Sympathy for the Devil” in Chicago. Photo by Chris Force

- The iconic Rolling Stones logo received a diamond-theme refresh. Photo by Chris Force

You must also be thinking about how the performance is going to read from portrait mode on a phone. Is that a composition that you have to consider?

Ray Winkler: Absolutely. I mean, I’m certainly not the TikTok generation, and I find Instagram a bit laborious and tedious, but I do understand the power it has over our modes of communication. Look at any one of these shots and you’ll see how many people are holding up mobile phones. We no longer live in the moment. We live to show people that we’ve been there, but we don’t really live that moment.

When I started my career, the pictures of the first show of a tour were heavily guarded and heavily curated. There was usually only one, maybe two, official photographers. There were certainly no mobile phones that could go in and just take pictures. That’s changed.

The very first person that comes in, takes a picture, and uploads it, and that picture goes viral, actually sets the tone for how subsequent photos will be perceived. You have to make something very photogenic, and as a result of that, often tone down some of the intellectual ambitions or some of the deeper thought processes.

What’s an example of that?

Ray Winkler: Well, you can reverse engineer a narrative. You can say that what we created here is a digital envelope for the Rolling Stones to exist 66 years into their career, within the absolute contemporary moment of today, with lots of digital surfaces. This does not dictate the geometry, though—that’s an architectural conceit. There’s an intellectual thought process that meshes technology with the cultural context of its time.

- For these shows, Ray says there’s an intellectual thought process that meshes technology with the cultural context of its time.

- As an entertainment designer, Ray is versed in the craft of turning an architectural idea into something that will look good on camera.

All of those things do not necessarily translate themselves into something that looks good and is Instagram-friendly. That’s where the architect in us comes in. As entertainment designers, we know how to take that architectural idea and turn it into something that will look good on camera.

I’m also curious about your process and where your energy comes from to still dive into this with so much curiosity and interest.

Ray Winkler: It’s true that you’re only as good as the team around you. At Stufish, we have a great team, and we work with some of the greatest people in the industry. They bring their expertise, energy, enthusiasm, and the ability to think out of the box, making the job interesting and varied.

At Stufish, we don’t have a house style. We build things from the bottom up. We’re fortunate when a band like the Stones is keen and engaged in developing ideas to maintain their relevance. Their presence is based on their incredible creativity and music. The Stones have been icons for over 60 years, and they always want to reinvent themselves. They look to us and other collaborators to pull something out of the hat each time.

There’s nothing worse than rehashing old ideas. We have a lot of hard work but the joy of being part of this process is immense. The audience votes with their pockets, and the tour is doing well, which is gratifying.

- “Mick came out and saw the design in Houston,” Ray says. “He’s always very generous and knows what he wants. If he doesn’t like something, he’ll let you know.”

- At the end of the day, the real client is the audience. “They are the ones we have to convince that it’s worth coming out, spending three hours, commuting, and spending money,” Ray says.

Has the band given you any feedback on the design, either before or after the design?

Ray Winkler: Mick came out and saw the design in Houston. He’s always very generous and knows what he wants. If he doesn’t like something, he’ll let you know, but he’s also very engaging in communicating his thoughts. At the end of the day, the real client is the audience. They are the ones we have to convince that it’s worth coming out, spending three hours, commuting, and spending money. Their continued attendance is a vote of confidence in the show.

What kind of feedback do you typically get from artists?

Ray Winkler: Every artist is different, with different setups. Some have direct communication, while others are indirect. In the Stones’ case, it’s more indirect, with Patrick Woodroffe as the creative director having his finger on their pulse. Some artists, like Lenny Kravitz, are very engaged and want to know everything. Our role is to make sure that when the artist turns up, there are no big surprises.

Okay, that turns us to Patrick Woodroffe. Patrick, you’re fresh off seeing the Rolling Stone perform in Silicon Valley. How was it?

Patrick Woodroffe: It was amazing—so exciting. You know, at the age of 81, Mick is still at the top of his game in front of 60,000 to 70,000 people. It was thrilling, and I’ve seen hundreds of their shows, but this one was special.

I saw the show in Chicago and also thought it was amazing. I had a great time.

Patrick Woodroffe: Let me tell you a nice story about Chicago. When I used to tour with the band, I would travel to all the dates. Quite often on American shows, I would go out into the parking lot to watch people tailgating. I often walked around and enjoyed the vibe. Some people recognized me if I had my pass on, and I would tell them about my work.

- The Stufish team doesn’t have a house style. They build things from the bottom up. “We’re fortunate when a band like the Stones is keen and engaged in developing ideas to maintain their relevance,” Ray says.

I remember one night telling Mick how fascinating it was, and I suggested he should check it out. In Chicago, I went out in the afternoon with our security guy and found a big RV at the end of the parking lot. There were about ten or twelve fans there, all of a certain age, who had gone to high school together and were celebrating the Stones. I didn’t say anything at first, but I went back to get Mick. We got into an ordinary runner’s van—just me, him, and Big Jim, our security guy. Mick had a cap on, and we drove up next to the RV. They were all inside playing guitars and songs.

You could imagine their disbelief when we walked in. I told them to keep playing, they were performing “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” Mick asked the guy where they were in the song, and the guy said, “Chelsea drugstore.” Mick started singing along, and it was amazing. He sang with them for a bit, didn’t hang around too long, but chatted with them. They all shook his hand. It was beautiful—a fantastic moment for me and for them. And this was back in the days before mobile phones, so there’s no record of it, which is a shame because it would have been a great piece of history.

The band mentioned in the Chicago performance that this was their 40th time playing here, and that they had first come to the city was nearly 60 years ago, a time when there would have still been rotary phones on the wall and cars without seat belts.

Now the show is happening with technology that is obviously laser-sharp and modern, with everything as current as possible, yet, they don’t seem out of place at all. How does that work?

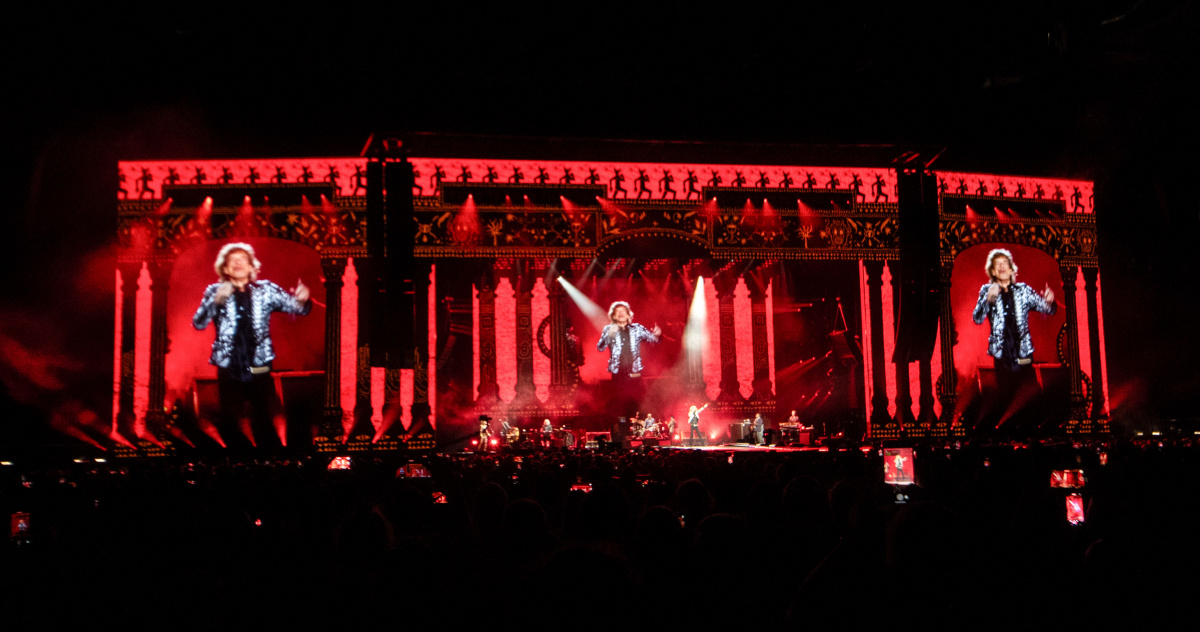

Patrick Woodroffe: You have it in a nutshell. For me, it’s manna from heaven to hear someone like you—a design guru—understand that this is a contemporary band. The fact that they’ve been going for 60 years is something almost academic. They have always been of the moment. They were the first band to start playing and touring in stadiums. No one had done that before, moving from arenas to stadiums. They haven’t been technical for the sake of it; they’ve been groundbreaking.

The Rolling Stones’ Steel Wheel tour, 1989. Photo courtesy Patrick Woodroffe

In 1989, they were the first people to create a stage set that wasn’t just a classic kind of box with some lights and maybe a banner on each side with the Rolling Stones tongue. They created the Steel Wheels and Voodoo Lounge tours, which were designed as dystopian cities by Mark Fisher, a designer I collaborated with over the years. They’ve always been at the cutting edge of doing new and exciting things, not tech for the sake of tech. That’s why they’re so comfortable in their skin. It’s not unusual for them to be playing on a modern, contemporary stage set.

It’s great that you’ve understood that they felt very comfortable in that setting, and that’s as it should be. I think we’ve succeeded if you have that response.

Ray referenced you essentially speak for the Stones when it comes to organizing the creative feedback from the band, managing the push and pull with the other teams. How does that work?

Patrick Woodroffe: I have much more to do with that because I’ve been directly involved for so many years, and these are friends of mine. I’ve worked with them, along with Chuck Leavell, the keyboard player. He and I are the longest-serving employees of the Rolling Stones, having done our first show in May of 1982. That’s a long time—over 40 years. I’ve really grown up with them and understand who they are.

- “In 1989, they were the first people to create a stage set that wasn’t just a box with some lights and a banner on each side with the Rolling Stones tongue,” says Patrick Woodroofe.

- “I’ve spent a long time with the band—over 40 years,” he says. “I’ve really grown up with them and understand who they are.”

Mick and Charlie Watts, when he was alive, led that side of how the band is put together. Things like album cover artwork were always Mick and Charlie’s domain, particularly Charlie, who was a graphic designer and an artist in his own right. The others are involved too, and I run everything by them. The actual conceiving and putting together is done by a very small team, really. It’s pretty much Mick and myself when it comes to conceiving what the show should be.

The tours are shorter and shorter now. We used to do 120 dates, which allowed us to amortize the stage set and design over that many shows. Now they only really commit to a dozen or, in this leg, 19 shows. We talk about what it’s about, Hackney Diamonds is the name of the album, and we wanted to tie that in somehow. It’s the first time they’ve toured with an album for many years.

You saw the graphic of the diamonds to start with. We like the idea of having a virtual stage set. We’re not committing to something like with Steel Wheels, where we committed to a dystopian city falling to pieces, Voodoo Lounge was about the internet revolution; it was modern, shiny, and silver. This tour is about presenting the band in a cool, modern way, with a wonderful sense of history behind them. That’s the setting we chose, allowing us to create a completely different feel for each song. All those songs, although they’re generally rock, are different. Each has its own lyric, tempo, and feel.

The Rolling Stones perform “Sympathy for the Devil.”

Some of the punkier, newer songs have a strong and tough feel, while “Sympathy for the Devil” is a huge art piece that deserves a completely different look. This gives us the freedom to create unique identities for each song while ensuring the whole production links together cohesively.

That’s why I like working with the same video company, Treatment Studio. Even though we bring in different filmmakers for different parts, the whole piece has to hang together. It’s not just visually with the lighting and video; it’s about the music, the choice of songs, and the order in which they’re played.

The band rehearses in Los Angeles for six weeks while we work on the stage, lighting, and video content design. Then we start in Chicago with a team to put together what each of the songs might look like, building the lighting cues and seeing how the video fits in. In their last week of rehearsals in Los Angeles, I spend time with the band listening to their songs and discussing the choice and order of the songs—what song we should start and end with, and how different acts within the show work.

“Until you’re there and see the scale, you can’t fully appreciate it. That’s when the real magic happens.”

—Patrick Woodroffe

This process is crucial; it’s not just a matter of picking hits and arranging them randomly. It’s a very conceived process, and we’re always considering how the visuals fit into the songs.

Then we have production rehearsals, where the lighting, video, and band come together. That was a week in Houston at the first venue where we opened the show. That’s when you really see it. All the work you’ve done over the last six months comes together, and you see how the band’s performance fits with the visuals on that scale.

It’s one thing to look at something on a video screen and have a sense of what it will feel like, but until you’re there and see the scale of something that’s 200 or 300 feet wide and 60 feet high, you can’t fully appreciate it. That’s when the real magic happens. You hope that you’ve got the bare bones and foundation right, because if you do, you’re really painting in the final details. That’s a fulfilling moment.

- “We’re always making notes on the lighting, saying, ‘Let’s come in a little earlier with that,’ or ‘Let’s put a little more focus over there.'” Patrick says. “I work a lot with the video director.”

Then, of course, there’s the moment when the show opens: “Ladies and gentlemen, the Rolling Stones!” You see your work come together, with no stopping and starting. That’s two hours of your work played out in front of you. Afterward, there’s a debriefing. We discuss what worked, what didn’t, and any changes that need to be made.

We might find that a certain song didn’t work as well as expected or that a video piece would be stronger if placed three numbers later. You’re constantly honing the piece, and then it settles down to become the show you have for the next couple of months. I came back to see the last show in LA at Sofi Stadium, which is extraordinary. We did some filming last night for future projects, and now we’re preparing for our last show tomorrow.

After you saw that first show in Houston, what did you shuffle around? Were there any major changes to the show?

Patrick Woodroffe: We’re always making notes on the lighting, saying, “Let’s come in a little earlier with that,” or “Let’s put a little more focus over there.” I work a lot with the video director. We have someone we call a screens director—a video maker who sits in a temporary studio built under the stage. He has about 20 monitors and a switching system, and he knows the music well, working from his script.

Generally, at that point, it’s fine-tuning. You’re making detailed adjustments to ensure the entire piece fits together.

“I’m very aware of Mick as a performer,” Patrick says. “I’ve seen hundreds of performances with him. I’m quite understanding of what it takes to command a stage like that.”

You’ve had this over 40-year friendship with Mick Jagger. Was there anything that he said to you about this show that surprised you? Is there anything he says that surprises you at all at this point?

Patrick Woodroffe: No, he doesn’t really surprise me. Somebody saw the show yesterday who I’m doing some work with on the project. He and his partner spent the day with me, and he said they were amazed on two levels. One is what it takes to put on one of these shows. It’s extraordinary. It’s 230 people on the crew and 60 people in the traveling entourage with the band. Well over 300 people, all of whom have prescribed jobs. The professional standard is very high.

There’s always an understanding that this is the Rolling Stones. We’re going to do it as well as it possibly can be done. But because they have such a confidence in who they are and what they are, and because all of us around them have it, therefore have this reflected confidence in what we’re doing, it’s very laid back. It’s not overly dramatic, with bodyguards rushing around and walkie-talkies telling people what to do and prescribed things. It just seems to happen in this rather comfortable way.

Second, they were amazed at the enormity and the prestige of a show at that standard but how it seemed to be done effortlessly. I think I see very much the same thing in terms of the way that we put the show together. We may all be friends and work together a long time, but we’re serious about the work. It’s a serious thing to really get it right, and we’ll do whatever it takes to get that right and spend whatever money needs to get that right. But we don’t waste money, and we’re not profligate like that. Everything is considered and thoughtfully done.

“You have to take the audience on a journey with you,” Patrick says. “You have to see the craft of how you work the stage. On those big stages, you don’t rush around immediately.”

I’m very aware of Mick as a performer. I’ve seen hundreds of performances with him, and I have to say, I’ve worked with many, many of the great performers in the kind of rock world over the last 40 years. I’m quite understanding of what it takes to command a stage like that, having seen it secondhand and seen the craft in it. It’s not just getting out and saying, “hello Cleveland” and just rocking out for two hours. There’s real consideration for the great artists.

To be a great performer, just like to be a great actor, you have to have trod the boards for many years, and you’ve had to have worked in small theaters and done difficult shows and to really learn what the responses of audiences are. Mick is a master of that.

You have to take the audience on a journey with you. You have to see the craft of how you work the stage. On those big stages, you don’t rush around immediately. You wait, and two numbers later, for the first time, you go out on the runway, stage left; that’s a big deal for the audience on that side; suddenly you’ve come towards them.

You somewhat famously have lived on a boat in London. Do you still?

Patrick Woodroffe: I’ve had two or three boats in London. Now we live in the West of England in a house that was built when Elizabeth the First was on the throne of England, and a little remodeling since then, as you might imagine. But previously our apartment in London was always a boat on the pier in Chelsea for 20 years. We would take the boat up and down the Thames. We’re now back on dry land, and we have an apartment in London, in Battersea Power Station. You know the famous Pink Floyd album cover with the floating pig? That’s Battersea Power Station.

I’ve been very happily married for nearly 40 years, next year to the same woman. I’ve had some real stability in my life.

Wow. What is the secret to staying married for that long?

Patrick Woodroffe: It never felt that complicated to us. I suppose, if I’m honest, we’ve been apart a lot. I always travel. When I first met Lucy, 40 years ago, I was touring. I would pack my bags, and I would be away for weeks at a time, sometimes months. I’ve still traveled a lot all over the world. We’re apart, and then we’re back together again. I think that has certainly been rewarding.

“I don’t quite know how to characterize it, but Mick is an extraordinary person,” Patrick says. He’s very confident about what he thinks about something and where he sees the Stones.”

If you’ve found a good partner in your life and somebody that you want to be with and able to share both in the successes and the failures—of which one hopes is a decent balance. That’s been a very solid part of my life, and I think it has made a big difference. I’m 70 now, so I’m pleased I have a studio with my partners that will continue long after I’ve gone—not so much as a legacy. There’s just been a lot of learning in 40 or 50 years, and that’s nice to be able to pass that on.

“You have to take the audience on a journey with you. You have to see the craft of how you work the stage.”

—Patrick Woodroffe

Is there anything else specifically you would say you’ve taken away from your working relationship with Mick Jagger?

Patrick Woodroffe: I don’t quite know how to characterize it, but he’s an extraordinary person. Mick, he’s very confident about what he thinks about something and where he sees the Stones. Of course he understands the importance of them and the legacy of the band, and one of the most important groups of musicians who are performing in that genre, but it’s still an old rock band as well. It’s just still a group of people playing music.

There was this nice dichotomy, and I think that’s probably a good lesson to learn. All the stuff in the moment feels terribly important. I don’t want to denigrate the fact that it is important, but it’s still a group of people putting on a show. Some people take themselves very seriously, and a lot of these artists are extraordinary. I find that the most successful artists are the ones who don’t take themselves too seriously.

Elton John doesn’t take himself seriously. Of course, he knows he’s important. Bob Dylan is the coolest dude in the world. He just gets up and plays his music. He doesn’t really want anything to have to be explained. I think they’ve given me a certain confidence.

If you can be that big and walk out on that stage in front of that many people to do a show that’s that important, and you can still be a decent person and not take life too seriously, I think that’s probably a good life lesson to take away.