Willie Williams, the acclaimed English stage designer, has brought his distinctive vision to “U2:UV Achtung Baby Live at the Sphere,” in Las Vegas.

Willie has been a pivotal figure in stage design since the 1980s, working with artists like David Bowie, The Rolling Stones, and George Michael, but is most widely known for the extensive work he’s done with U2. In his newest collaboration with the band Willie delved into the innovative environment of the Sphere—a Las Vegas venue that aims to redefine the live performance experience.

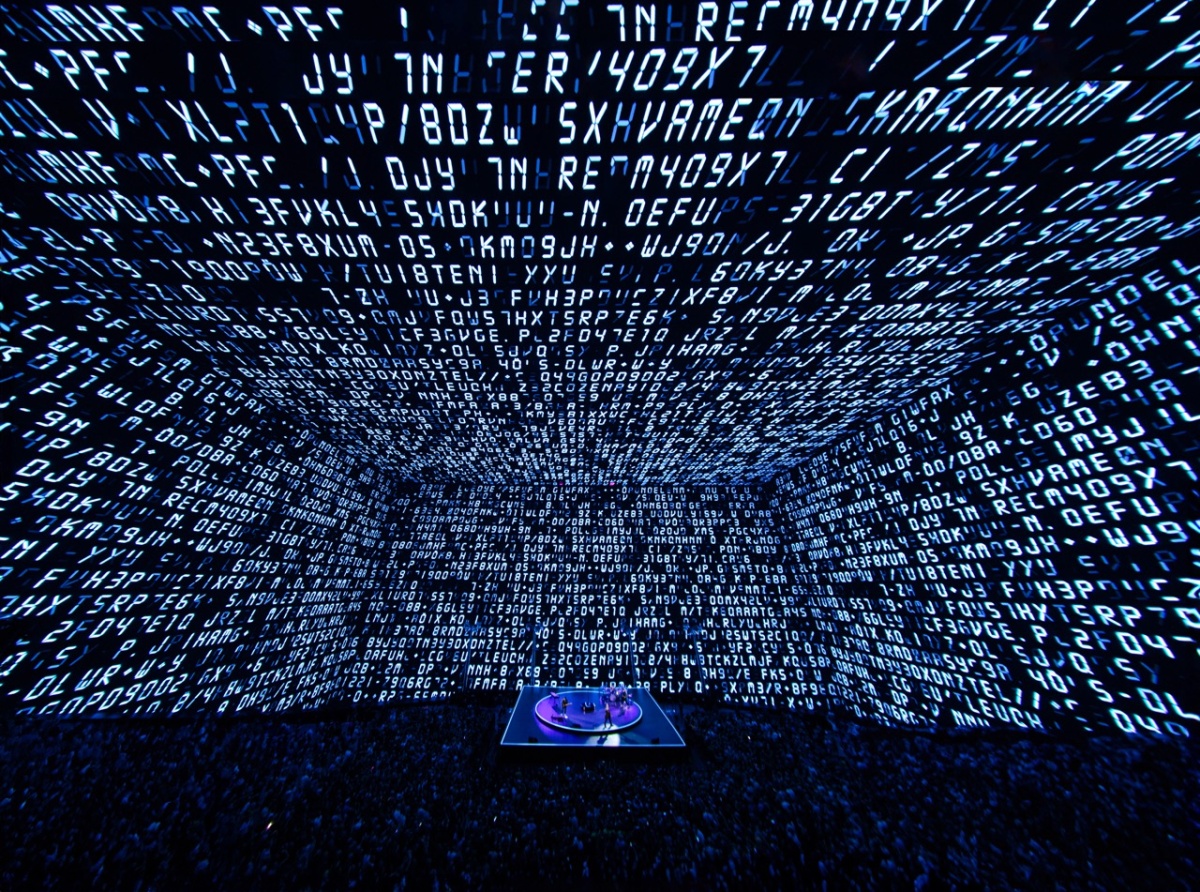

The Sphere, created through a collaboration between Madison Square Garden Entertainment Corp. and several leading technology companies, features an interior LED screen that covers more than 160,000 square feet, boasting the highest resolution of any screen in the world. Coupled with a custom-designed sound system, the Sphere offers an immersive experience that is unparalleled in the industry.

In U2:UV Achtung Baby Live at the Sphere, Willie leverages the Sphere’s cutting-edge technology to craft a show that goes beyond traditional concert norms. His work, renowned for its ability to blend artistic creativity with technological innovation, finds a new canvas in the Sphere’s advanced capabilities. I spoke with Willie about the new show and his extensive career that has lead him up to this moment.

Chris Force: Have you been spending a lot of time in Las Vegas with U2?

Willie Williams: I have I have been here off and on since July 31, which is more than any human being deserves.

Before we talk about U2 I want to talk about one specific point in your career, purely for selfish reasons. I believe you got your start in the industry with one of my favorites, another Irish band, Stiff Little Fingers? I imagine that would have been a formative time for you.

Indeed, and for live music really. Just as I was leaving high school punk rock was happening in the UK and that really changed everything for the nation.

I was bright, I did well at school, was all set to go to university but really didn’t have any direction. I was going to go into the sciences because that seemed more practical than wasting time in the arts. Also, I grew up in the north of England in the 1970s where there weren’t exactly lot of people whispering into your ear, “Have you considered the creative arts as a potential career?” So I pretty much ran away and joined the circus.

I had friends who were in bands, and I would go and hang out and help out. At the time during punk visual presentation was frowned upon really, at least appearing to care too much about it was frowned upon. There were a couple of art school bands I really loved who I spent some time with. Neither of them really got anywhere, but I mainly started working with lighting and started to get quite good at it.

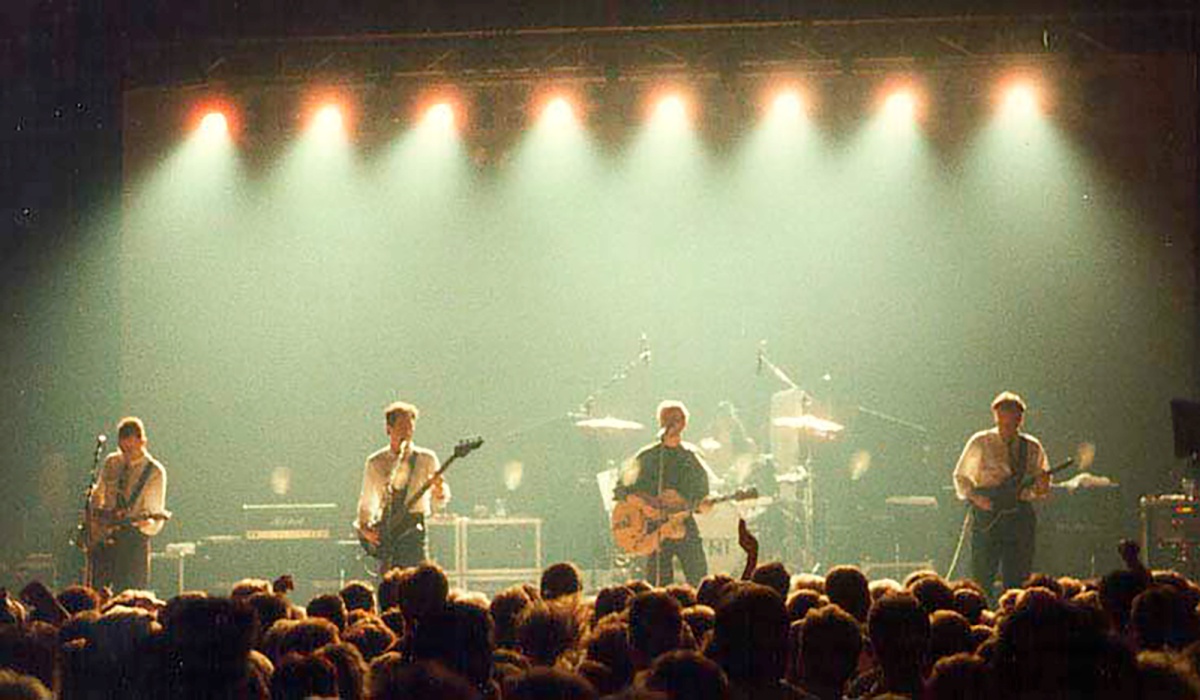

Stiff Little Fingers stage, France, 1981. Courtesy of Willie Williams

Stiff Little Fingers was the first band I worked with who anyone had heard of. The first thing I did with them was a month in France doing all these punk clubs. They hated to have time off; they got so bored they were just doing as many shows as possible. I remember we did 32 shows in 33 days in all these tiny little punk clubs in France. Can you think of that many towns in France that would have little basement clubs? But it was exhilarating, a very small crew, and the energy of that period of time was quite wonderful.

Stiff Little Fingers perform in France in 1981. Courtesy of Willie Williams

I did some larger things with them, a couple of headline UK tours, which was really going well until they decided to call it a day, at least for their first incarnation. By then I had come across this other Irish four piece called U2. I loved their first record, it just resonated with me so much. I thought, ‘Well, I probably got enough know-how now to just go and find out where they are and approach them.” Oh, and of course, U2 were fans of Stiff Little Fingers. So in a way Stiff Little Fingers were a good calling card when I was first trying to ingratiate myself with the then fledgling U2. So I do owe them a little something, I think.

I want to go back to where you said the visual presentation in punk was frowned upon. I’m imagining, being in some of these little clubs, the idea that you might have some light show or effects would feel like blasphemy. What was your strategy to not lose the audience, to not turn everyone off with your design but find a way to add something to an audience not expecting visuals?

Well, it’s ironic, because obviously in the larger sense the visual presence of punk was incredibly strong and is still completely iconic. I mean, anything from that period is immediately recognizable. I think it was finding a way to work within those parameters in a way that brought some mood to the performance, a bit of energy, but you know my options were incredibly limited. I was often going into a place and using whatever was available there; you go in and try to make a show.

U2 perform at Red Rocks, June 5, 1983. Courtesy of Willie Williams

Certain principles—the way you can light people, the way you can create mood, the way you can bring energy and variety to performance to take an audience on some emotional journey—those kinds of things can be done very simply and in a way that wasn’t considered too vulgar during those times. That’s really where I cut my teeth, trying to make something out of next to nothing.

Even now it’s ironic given that I’ve done some of the biggest shows that have ever existed, but in my mind I still take a very minimal approach to design. I try and pare it down to one thing if possible. It’s one idea, you know, the stage is this one thing, or the stance is this one particular stance. All that comes from having started having to make something out of nothing every day. Even here at the Sphere, it’s in one sense a very simple idea, the stage is a very simple idea, just on a slightly larger scale, than what I was doing with Stiff Little Fingers.

So the real lesson from those early times in your career was being able to make something from nothing. Were there other parts of your creative process that formed during that era?

I think understanding color. It’s funny, I was looking at a London band called Writz who I worked with for a couple of years, and we were very close. They had a little light rig; we had about 10 lights we would carry around, which was luxury beyond words. I was looking at some color slides taken from that period, and I was kind of fascinated with them because I know I had 10 lights; that’s what I had. And these pictures just looked amazing. I have been trying to recreate some of it. A lot of it I think has to do with they were color slides; it was like Kodachrome so the colors are absolutely beautiful. Also they would have been tungsten lights, so the quality of the light is different from what you get with LED. But certainly color was an element to work with in very small spaces.

Even simple things like how often you change the environment, how often you change the mood—do you flash the lights the whole time? Or do you trust that the audience can be engaged by a strong look that just sits there? All of these things were really, really good lessons that I just had to figure out for myself, but seeing the way it worked day to day and being in a different space every day was really good training.

David Bowie & Willie Williams, 1989. Courtesy of Willie Williams

What did you learn from working with David Bowie?

Well, funnily enough the first thing I did was Tin Machine. In a way that show epitomized everything I’ve just been talking about because he had just done The Glass Spider, which had been generally ridiculed. Even though now it’s ironic, if you can find the concert video of Glass Spider, it is absolutely the template for all the diva shows—all your Taylor Swift and Beyonce shows now where you have a setup, you have a big scene, and it stays there for a while, and then there’s a big change of scene and a costume change. That’s what it was. It’s just unfortunate. It was about 20 years ahead of its time.

Tin Machine, Town & Country Club, London, June 27, 1989. Courtesy of Willie Williams

So he was done with that; he just wanted to be in a grunge band. He found Reeves Gabrels, who’s an extraordinary guitarist, and off we went. He was playing, in (David Bowie’s) words, “absolute shitholes.” The goal was to find these absolutely terrible clubs to go and play in. We took a little light rig with us. But what was really delightful was the lighting stance was incredibly minimal. It was a real performance art.

He had seen a production of Metamorphosis. Baryshnikov did a production of Metamorphosis on Broadway, and he loved the lighting. It was these very simple four or five elements, there was a very strong backlight, and there was a sidelight and then pools of light. That’s what he wanted to do, so that’s what we did.

What I really learned from David Bowie was that you can push that idea much further than I would have dared. If you can trust that the performance and the sound is compelling enough, you can sit in one state for a long time. Sometimes there’d be two or three songs, and there’d be like a 10-minute period where nothing would change visually. Then, when something does change, it has a huge impact. It was such a challenge I had to write a little note I put on the lighting console that just said, “Leave it alone.” Just trust that this is going to sustain. It doesn’t hurt when you’ve got David Bowie onstage.

I did both Tin Machine tours, but I also did Sound and Vision, which was the big retrospective he made with Édouard Lock from La La La Human Steps in Montreal. That combined film projection on an invisible front gauze with live action. I got both extremes with him, which was a real treat. That really was the beginning of my being able to engage with very large images in a performance. It was definitely one of the building blocks that went into Zoo TV, which was a couple of years later.

U2, Zoo TV Tour 1993. Courtesy of Willie Williams

What does the quote, “When there’s nothing you can do, do nothing,” mean to you? How has that impacted your career?

People ask me for the best piece of advice I got in my early years. It was from a guy called Andi Banks, who was the tour manager for Stiff Little Fingers. So much is out of your control when you’re touring. You’re in a small venue, or it’s not your gear, or any million other things that happen on a day to day basis. Another way of phrasing that is, “Prioritize and work on the things that you can affect.” But when there’s absolutely nothing you can do, don’t run around like a headless chicken. Preserve your energy and think and make a plan. That piece of advice never grows old.

Are you still writing a lot? Does that impact your creative life at all?

Well, yes, it’s all part of the same output, I suppose. In thinking about a new project it’s very helpful to write down a description of what it is I’m trying to do because I can write in much more detail than I can draw. There are all the things that can’t be drawn—what you hope the audience feels, and what you hoped. Also, I think it helps give me a sense of a body of work that’s genuinely my own. I’m no longer afraid to draw from that.

“Prioritize and work on the things that you can affect.”

I’ve always hated to repeat myself and often envied some of the fine artists who, in the best possible way, had one idea and went with it for 50 years. Sometimes when I’ve looked at my back catalogue, it’s a bit all over the place. But now I’m not afraid to draw from that. I’m just trying to make sense of what I’ve been doing for the last 40 years really. I’ve kept journals since I was 15 years old. The great thing about keeping a journal for long enough is it becomes therapy.

I write far more when things are not great versus when things are great. I like to say I’ve got about 30 years of complaining. But it’s an amazing thing to do. They’re mostly handwritten in small books—absolutely illegible to anybody other than me. During the pandemic, when we were looking at things to do, I started to delve in a bit because I never had revisited them. It’s been quite interesting. I’m not sure what they are. It’s certainly not a kiss and tell, and it’s not a textbook. But it’s interesting to look at the patterns that emerge. There was quite a lot of self-knowledge that came from seeing things I was doing 30 years ago that relate to what I’m doing now, without any real conscious connection.

R.E.M., Up Tour, 1999. Courtesy of Willie Williams.

Is there any of that self-awareness you can share? Is there something in your journals that has helped bring clarity to why you do what you do?

I think coming to understand that the things you think are obvious may not be obvious to everybody. That kind of defines your talent, what it is that you might be good at. Very early on there were so many things I would see, or I’d go to other shows and think, “Why on earth wouldn’t they do that?” And the simple answer was because no one thought of it. So that’s the sort of self-knowledge I’ve found useful—really understanding what it is that’s yours and trusting that, or having the confidence to go with it.

Omnia night club, Las Vegas, 2015. Courtesy of Willie Williams

You’ve said one of your favorite venues is The Fox Theatre in Detroit, which I found surprising.

It was just beautiful. I went through a period with early U2 and with other people, playing in these incredible theaters in the USA. When you come from an island as small as Great Britain, just the scale of the US is absolutely extraordinary. Every town you go into has half a dozen of these magnificent theaters.

There was something about The Fox I really loved. I used to love getting up into the roof spaces of these places because some of the older theaters have these massively complex, curved, domed or multiple domed spaces all made of wood, which was obviously hand-carved. It was before computer routing, and the craftsmanship was awe-inspiring. They were relics.

George Michael, 25 Live Tour, 2006. Courtesy of Willie Williams

Do you have favorite audiences? Not the venue itself, but the people who fill them?

It seems the further south you go the more an audience views a show as something to come and participate in rather than something to watch. Italy and Spain have always been pretty nuts. And then South America, just forget it. I mean, once you get down into South America, it’s just the religious experience of some of these things. The U2 360º Tour, we did three nights in Mexico City in a stadium. And because the show was playing in the round we could get more people in. There were 108,000 people in this building, and we did three nights. Because there are more people the audience is louder, and the venue was kind of bowl-shaped so everything gets amplified. I remember coming away from the second one in particular and Bono just saying, “Well, that was Everest.” It’s an audience who is not trying to be cool, who just wants to be part of this thing—they’re my favorites.

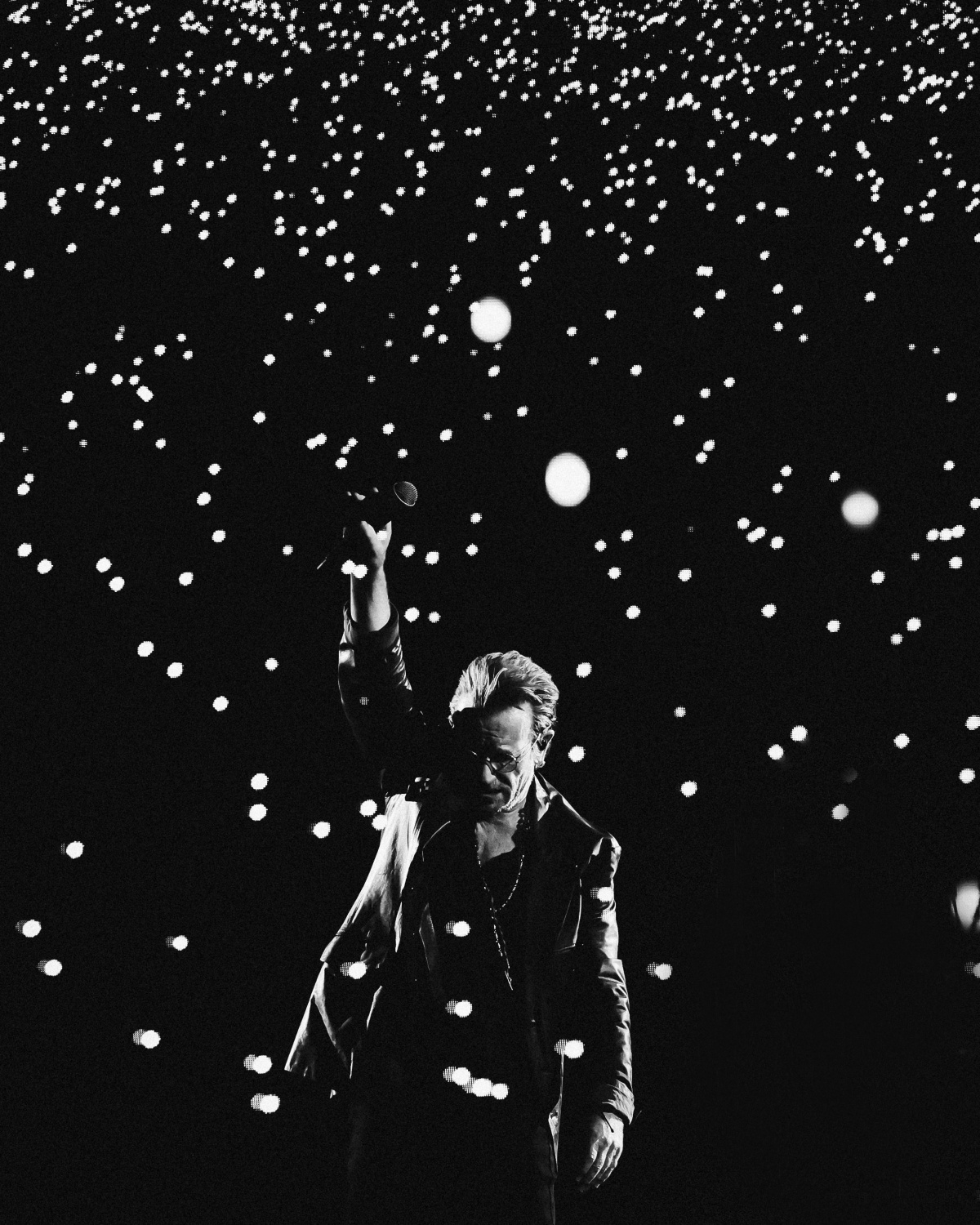

Bono, The Edge, Adam Clayton and Bram van den Berg of U2 perform during U2:UV Achtung Baby Live at Sphere on September 30, 2023 in Las Vegas, Nevada. Photo by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for Live Nation

Where does the Vegas audience fit into the “cool” versus “we came to participate” scale?

It’s a curious one. We’re still finding out really, but nobody is from here. When you’re touring there’s an energy that comes simply from traveling. There’s also an energy that comes from: next up is New York or next up is London or Berlin. You can tailor a show a little bit; you get an audience with a different character. Here in Vegas we have people from literally from all over the world every night.

In some ways I’m finding the character of the audience a little more uniform because probably the breakdown of the audience is fairly consistent in terms of the number of tourists who are coming to see it because they’ve heard it’s a good thing to do.

One of the funny things about (the Sphere) is because it’s so dead acoustically, the shape of it, and everyone’s facing in the same direction, when you’re in the certain parts of the building it’s hard to hear the audience. I will wander right into the audience so I can really hear what’s going on. And yeah, they’re loud, and they’re doing what they’re supposed to do. The best place to be to hear the audience is standing on the stage because everyone’s facing them, so I think the band is having a great time.

For years and years we’ve designed U2 shows to accommodate a really wide demographic. There are youngsters who still want to be at the barricade on the floor, standing tickets really close to the stage. So the standing room, closest to the stage, that’s the cheapest ticket in the building. And then for the grownups who want to see a program, we can accommodate them, too. But what’s lovely is that the audience on the floor will become part of the show for the people who are up in the seats. Their energy really carries.

King Size by Marco Brambilla. Photo by Rich Fury

Can we go back to about a year, a year-and-a-half ago when you were introduced to this project? Could you talk me through how the project was initially explained to you and what instincts might have kicked in?

Well, even before U2 was approached everybody in the industry knew about this building because most people had been consulted. Treatment Studio, which is my design studio, made a kind of brochure of what the building was and how it would work for concerts for them.

I’m on record as saying I wasn’t very keen. Largely because pragmatically, for me, the show produces the video screen rather than the video screen producing the show, so that felt the wrong way around. Also I’m really not a fan of this town. I think nine shows in a row in one city is the most U2 has ever done. Now they’re up to 36.

Of course Bono has great instincts for what they should be doing. And really the most compelling argument was, “What else are we going to do?” We can go and play in a known format, or we can take a punt on this building and see what happens. None of us really expected it to have this level of high profile, and certainly we’ve been absolutely blindsided by just how globally the show has been received. I mean, it’s breathtaking.

There’s ever so much about this building that’s completely contrary to what you would want for putting on a show. There’s nowhere to put anything, there’s no underworld, there are no lifts, there’s no space underneath the stage, it’s a concrete floor. There’s nowhere to put any lighting because you’re surrounded by the screen. It’s very difficult to load in, there’s nothing about it really that’s ideal for performance. But we’ve managed to make it all work. I’ve come to embrace it.

- Photo by Rich Fury

Once you decided to commit to the show was there an overall theme or vision you used to kick off this process? How do you start thinking about making something like this that hasn’t been done before?

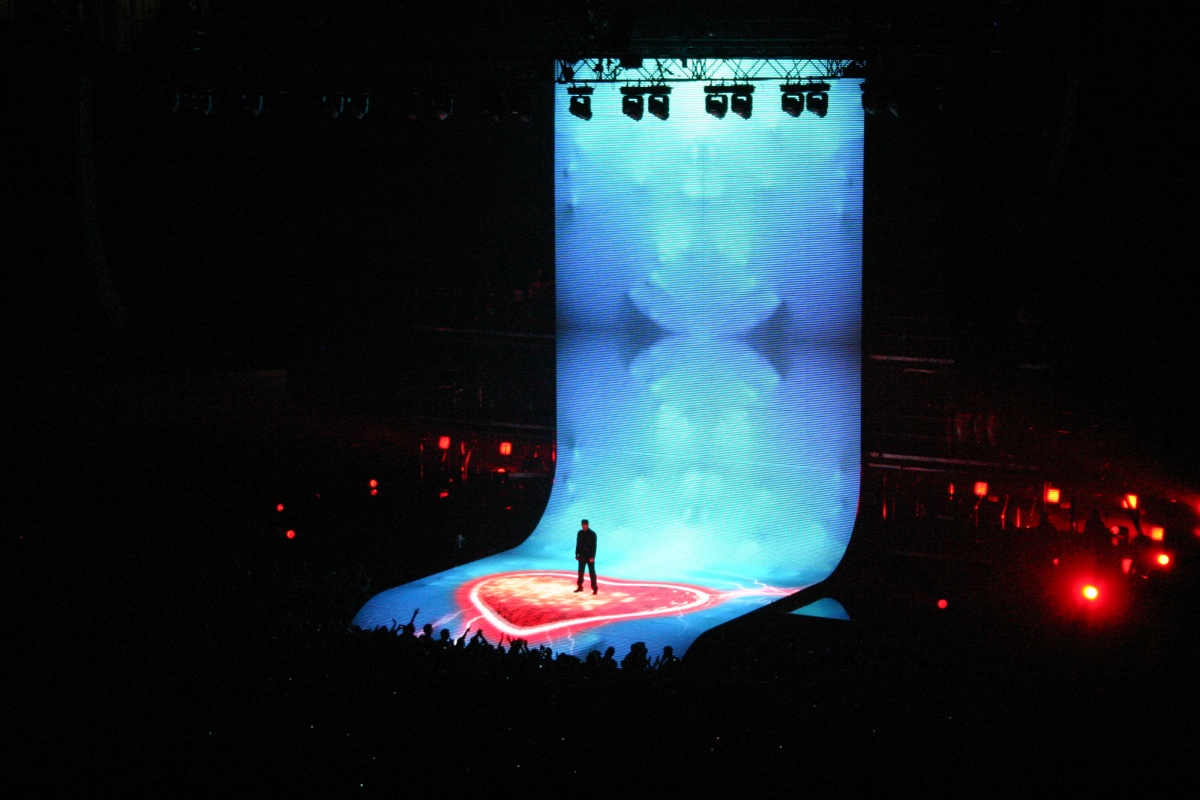

We had to imagine the building as well as imagine the show. The seed we had was “Hey were going to perform Achtung Baby!”

I also had a huge breakthrough in about February of this year, realizing that very simple graphic material could work incredibly well in this space. It’s made for these immersive movies and really full environments, but actually very simple stuff worked very well, particularly because there are no corners so you’ve got no points of reference at all.

We navigate the spaces we’re in by corners, and when those are removed it’s really easy to create wonderful illusions. The shape-shifting possibilities of the space are quite wonderful, and what’s lovely is the band has enough confidence to let the audience go for a moment. “Let’s all do this amazing thing and then we’ll come back together again.” That was a real turning point for me.

Then quite quickly it became there are sort of three phases to the show where we start with this 21st century take on where Zoo TV left off. Then we end the show with much more cinematic stuff, the kind of thing the building was designed for. In the middle we kind of take a break; we have Brian Eno’s record player stage, and turn the screen off and let U2 do that thing that they do, where they can play with absolutely nothing and still be the most compelling live band you’ve ever seen.

Flag by artist John Gerrard. Photo by Rich Fury

It doesn’t seem like every artist would be successful in this kind of format.

A question that comes up a lot is who is going to follow U2 in here now. I have no idea. U2 has made it look so easy, but there’s a massive learning curve for anybody coming in. Bruce Springsteen obviously is equally compelling and can perform in nothing, but he’s just not very interested in doing giant presentations.

When the building was first announced, there were these references that it could use vibration or pipe in certain smells and that the audio could be so specific that one guest could hear one thing and another could hear something totally else. Were any of these tools were at your disposal?

We wondered about the haptics, but the thing is, so few people are sitting down, it’s a bit pointless, really. And frankly we ran out of time and energy so we picked our battles. Everything else, all of this stuff like the smells, are deployed on the floor for the movies; none of that is there for the concerts. I think we would have ended up in a blind alley if we’d gone too far down that line. We didn’t really know how any of this was going to play. Until opening night there had never been an audience in there before.

Artwork by Es Devlin. Photo by Rich Fury

What were your takeaways the first time you actually saw the show?

I knew this was going to be an extraordinary show. Six months ago I really started to get on top of it. I had a storyboard from about March; we had to make decisions way earlier than they would normally. Once the show was locking in I knew this was going to be remarkable, so I wasn’t worried at all. The technology, obviously, could fail, but there’s absolutely nothing I can do about that. And when there’s nothing you can do, do nothing. I was just excited to be honest. The thing is with U2, every time they go out, they put their whole lives into it.

Photo by Ross Andrew Stewart

How did you go about choosing some of the other artists and designers you worked with?

Es Devlin has always been a great collaborator. She directed the two pieces to close the show. She also serves as a creative consultant on the whole project. She’s great.

John Gerrard is an Irish artist, and Bono had seen his work and it really resonated with him. His flags kind of bookend different sections. And then some were just lucky. Marco Brambilla, who makes these absolutely, overwhelmingly dense collages of characters rotoscope from movies. I happened to see some of his work and thought he was right. I got in touch and he had the right kind of attitude; there has to be a lot of give and take.

There’s a lot of diplomacy when working with the fine art world. These people all need to be able to see the bigger goal, which is the show. It’s trying to get the best out of people and helping people relax into making it a generous collaboration. The boundaries get very blurred, and there’s a certain preciousness of the art world that just doesn’t work here.

How did you get these high-profile artists to relax and trust you?

Well, hanging out with a bunch of rock stars doesn’t hurt. I always quote Julian Opie. He said, “Nobody applauds in an art gallery.” None of these people work in an environment where you’d get thousands of people losing their shit. But the U2 guys are all art collectors anyway, and they really understand that world. When those people meet there’s generally a meeting of the minds. There’s an understanding that we’re not here to exploit; we’re here to make something great together that neither of us could make by ourselves.

Did you get any feedback from the band that surprised you?

I was surprised by how easily they embraced the whole thing. I think it’s partly because they understood this is not an environment in which you can make quick changes. I always put a section of the show where they can kind of do what they want, and that was enormously helpful.

What are you working on now?

I’m doing a small play at the Trafalgar Theatre in London about a female drone pilot. I love to work on such extreme scales. The creative connection is incredibly rich, and that’s really the only thing I care about. It is nice to work on a small scale where very small gestures can have a big impact.