The terror of the blank page. If you’re a writer, designer, illustrator, or pretty much any kind of creative person, chances are you’ve felt the sting of creative block. Maybe a deadline is looming and you need to get the creative engine revving, but all you get are sputters and wheezes—and perhaps an ever-creeping sense of panic. “I suffer as always from the fear of putting down the first line,” John Steinbeck once wrote. “It is amazing the terrors, the magics, the prayers, the straightening shyness that assails one.”

But it doesn’t have to be such a terror. Creative minds have developed an endless list of rituals, routines, tips, and tricks to spur inspiration—or simply help you get over yourself and start the work. Here are a few creative ideas—co-signed by creatives—to attack the block, assuming of course that such a thing actually exists.

Writer’s block is a fiction as far as George Saunders (“Lincoln in the Bardo,” “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline”) is concerned. PHOTOGRAPHY BY ALENA SAUNDERS.

Are creative blocks bullshit?

Before we prescribe remedies, it’s useful to ask whether the condition should even be recognized. For psychologist Susan Reynolds, the answer is “no.” She locates the origin of writer’s block with 19th century poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the “indefinite indescribable terror” he felt at producing work he deemed unworthy. “French writers soon latched onto the idea of a suffering connected to writing and expanded it to create the myth that all writers possessed a tortured soul, and were unable to write without anguish,” Susan wrote.

George Saunders would likely agree; he told us last year that writer’s block is “not a real thing.” He invoked the late David Foster Wallace in his explanation, calling such blocks “just a form of incorrectly heightened expectations of yourself. So you write something and you say, ‘Oh my god. This doesn’t meet my standards.’ And you delete it.”

The best defense is a good revision process, and don’t be afraid to embrace the junk, he told us. “Because even then if you write a page of garbage, that’s not a problem,” he says. “You can revise it until it’s good. If I felt like I had writer’s block I’d just write a page of nonsense and then start tweaking it and saying, ‘Is there anything in here that has any energy? Oh, there is. OK, there’s four lines. OK, cut the rest of it and start over with those four lines.’”

Author Anne Lamott, of “Shitty First Drafts” fame, delivers a TED talk in 2017. PHOTO VIA FACEBOOK.

Fight writer’s block with “shitty first drafts”

George’s advice echoes a famous—and famously helpful—bit of guidance: novelist Anne Lamott’s embrace of “shitty first drafts.” In Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, Anne ruminates on the workaday anti-glamour of the creative process, with a particular focus on accepting one’s early-stages dreck. It’s worth quoting at length:

“For me and most of the other writers I know, writing is not rapturous. In fact, the only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really shitty first drafts. The whole thing would be so long and incoherent and hideous that for the rest of the day I’d obsess about getting creamed by a car before I could write a decent second draft. I’d worry that people would read what I’d written and believe that the accident had really been a suicide, that I had panicked because my talent was waning and my mind was shot.

The next day, I’d sit down, go through it all with a colored pen, take out everything I possibly could, find a new lead somewhere on the second page, figure out a kicky place to end it, and then write a second draft. It always turned out fine, sometimes even funny and weird and helpful. I’d go over it one more time and mail it in.

Then, a month later, when it was time for another review, the whole process would start again, complete with the fears that people would find my first draft before I could rewrite it.”

Anders Brasch-Willumsen’s “A Lucid Dream in Pink Sleep Cycle No 5.” COURTESY OF STUDIO BRASCH.

Don’t wait for inspiration; make it

Famed painter Chuck Close once notably derided the very notion of inspiration, dismissing it as the stuff of amateurs. “The rest of us just show up and get to work,” he said of his grindstone approach. “I never had painter’s block in my whole life,” he added.

Indeed, as the Center for Writing Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign makes clear in their tips for conquering block, what some mistake as inspiration is often really “the result of internalized hard work.”

When we spoke with Anders Brasch-Willumsen, art director and founder of Stockholm-based creative studio, he evangelized doing the unglamorous work and techniques of the ideation stage—mind maps, sketches, mood boards—but similarly threw cold water on the idea of inspiration, and employing tricks to locate it. “I don’t believe in hacks in order to get motivated,” he said. “I love what I do, so motivation is always present.”

“I think that we must know how to take breaks to be more productive in front of the blank sheet.”

– Alexandre Touguet

And even if a creative routine doesn’t always immediately yield excellent results, chances are it will offer fresh perspective. “People tend to lean on process as if going through the motions will somehow magically kick out an amazing product,” said Peter Bristol, head of industrial design at Oculus. “I guess I feel like you design by whatever means necessary until you have ‘the idea.’ The process really just provides you with different ways of looking at the problem.”

Some creatives swear by the “morning pages” routine. But it has to be longhand, and it has to be first thing in the morning. PHOTO VIA PIXABAY.

Get around the block with “morning pages”

A common chorus among creatives is that getting something on the page—even sometimes before the shitty-first-drafts stage—is paramount. That might help explain the popularity of the “morning pages” phenomenon.

Outlined in her 1992 bestselling book, The Artist’s Way, a collection of techniques to access and sharpen one’s creative potential, Julia Cameron suggests that, first thing in the morning, artists write three longhand pages of whatever happens to be on their mind. Simple enough, but the restrictions are what deliver results, urge morning paper advocates. It must be longhand, and it must be in the morning. It’s a way of turning off one’s self-censor and circumnavigating neuroses.

“We learn to hear our censor’s comments and say, simply, ‘Thank you for sharing,’ while we go right on writing,” Julia writes of the method. “We are training our censor to stand aside and let us create. The pages may seem dull to you, even pointless, but they are not. Remember that they are not intended to be ‘art.’ They pave the way for art. Each page you write is a small manifesto. You are declaring your freedom—freedom from your Censor, freedom from negativity in any quarter.”

As you may have gathered, there’s a new age-y quality to Julia’s writing that may pose a hurdle for some. (The Artist’s Way was originally titled Healing the Artist Within after all.) But some of the most vocal boosters of morning pages are former skeptics, including Guardian psychology columnist Oliver Burkeman and comedian Patton Oswalt, who likened it to meditation, yoga, and (nice gag) bathing—things that seemed “ludicrous” at first blush but proved profoundly helpful.

Be they morning pages or some other form of positive restriction, self-imposed constraints have proven useful for countless artists and creatives. As multimedia artist Trey Speegle once said, “You have to set up the narrow parameters that you work in, and then within those, give yourself just enough room to be free and play.”

Know your weaknesses, but then push through them with practice, says Stephen Silver. COURTESY OF STEPHEN SILVER.

Practice makes the perfect antidote to writer’s block

From Anne’s just-get-something-on-paper approach to Anders’ rigorous sketch work, one sees a consistent theme in terms of pulling oneself out of a slump, or avoiding them in the fist place: Successful creatives put a major onus on (surprise!) practice. Artist and cartoonist Stephen Silver (Kim Possible, Danny Phantom) specifically highlighted the importance of continued creative exercise when he shared his wide-ranging professional advice.

He recalled a stretch of heavy turnaround work—where an illustrator has to draw a character from every possible angle. “I was told that I needed to improve my construction,” Stephen said. “That’s why I studied the technique and practiced. When I have to focus on anatomy or draw an animal I’ve never drawn before, I know I’m not going to be good at it. I just keep practicing.”

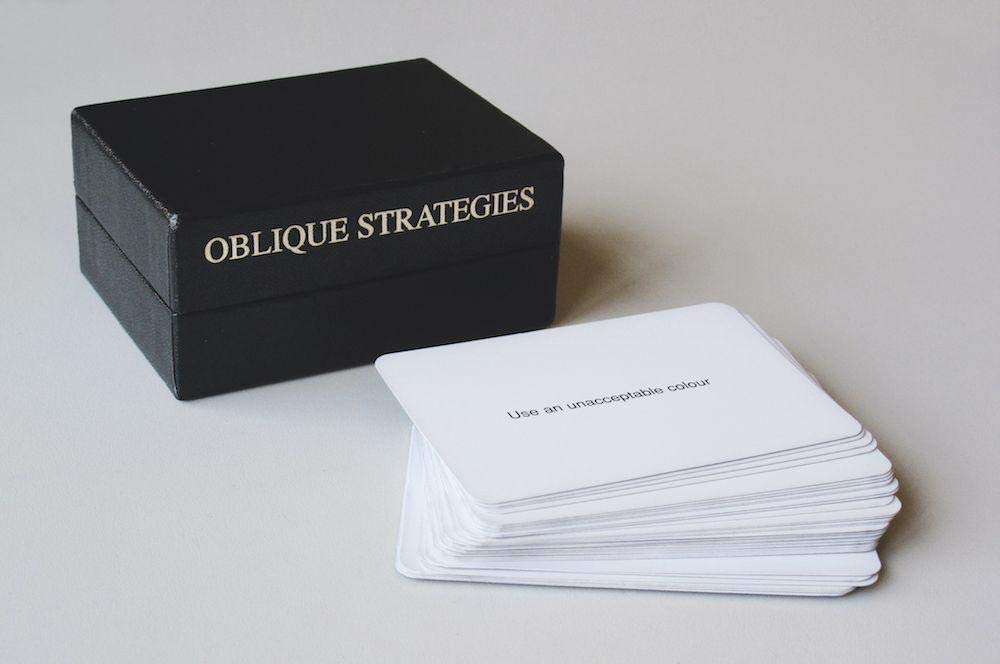

Brian Eno created Oblique Strategies with friend, collaborator, and fellow artist Peter Schmidt in 1974. Prompts include “Try faking it!” and “Only one element of each kind.” PHOTO VIA WIKIPEDIA.

Take an oblique attack against creative block

Art-glam and ambient pioneer Brian Eno is most famous as a musician, of course, but he’s also an accomplished painter, sound artist, and visual artist. So it shouldn’t surprise that the famous workaround device he helped develop, the creativity-sparking Oblique Strategies card set, similarly cuts across pretty much any discipline in terms of effectiveness.

Taking influence from the I Ching, John Cage’s penchant for gnomic aphorisms, and George Brecht’s own card set of commands, Water Yam Box, the Oblique Strategies deck features a creative instruction—sometimes direct (“Look at the order in which you do things”), sometimes, well, oblique (“Ask your body”)—on each card, ready to access whenever you stumble into an artistic roadblock.

Those who’ve worked directly with Brian have championed the cards’ efficacy—and how they sometimes challenge artists to rethink the concept of success and breakthrough. “Working with Brian and [former Roxy Music guitarist] Phil [Manazanera] was always exciting,” recalled Bill MacCormick, bassist for Eno/Manzanera side project 801, in Dave Sheppard’s biography of Eno, On Some Faraway Beach. “You never knew what would happen next and, of course, if all else failed we knew what to do — consult the Oblique Strategies. We might not agree on how to interpret the message chosen but it was always fascinating and usually threw up something that would spark a good creative thought. My favorite card, though, was ‘Honor thine error as a hidden intention.’ It was a great cover-all for any bum notes I played!”

Writer’s block gets seriously bad in Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 horror masterpiece. COURTESY OF WARNER BROS.

Create something out of your creative block

There’s actually quite a bit of art out there that takes creative block as its subject matter, which is surprising on one hand, given the subject’s nature, but wholly unsurprising given the fact that so many have grappled with it. So if nothing else seems to click, why not explore the block itself?

It’s a tricky move since, well, art has subtext. While movies like Barton Fink, Adaptation, and The Shining are all nominally about the torture of creative roadblock, they’re also about the rise of fascism, art versus commerce, and colonial genocide, respectively. So you’ll eventually have to dig deeper. But if you’re willing to explore the parallels between your own artistic struggle and others, you may stumble onto fertile ground just yet. Maybe cue up Eminiem’s “Talkin’ 2 Myself” or Jets to Brazil’s “I Typed for Miles,” both of which dramatize the struggle against creative barriers, for some inspiration—assuming you believe in such a thing.

Award-winning author Lorrie Moore has some deliciously tart advice for block sufferers. PHOTOGRAPHY BY ZANE WILLIAMS.

Give up! Or at least take a break

And if all else fails, there’s always forfeit. Acclaimed author Lorrie Moore pulls no punches with her suggestion. “I’m a little harsh,” she told the Telegraph in 2009. When people say, ‘I have writer’s block. What do you suggest?’ I say, ‘If you can’t write, don’t write. No one needs your writing. Don’t torture yourself.’” This is, after all, the same author who began her “How to Become a Writer story” with: “First, try to be something, anything, else.”

As much as that tickles us, it’s probably worth dialing back the extremity. The Harvard University Extension School, for example notes the importance of breaks. Think of it as mini-surrenders, but useful. Recent studies have shown that breaks foster productivity, motivation, and reduce “decision fatigue.”

Movement breaks can be particularly fruitful, according to James A. Levine, a professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic whose studies have shown the detriment of sedentary days. “The design of the human being is to be a mobile entity,” Levine told the New York Times in 2012.

Industrial designer and former Philippe Starck mentee Alexandre Touguet spoke about balancing creative fire with the need to decompress. When he started his practice, he’d constantly think about certain projects, sometimes interfering with the work-life balance. “To be a designer is to be passionate, and it is true that it can be difficult to differentiate professional and personal life.” Alexandre told us. “Nevertheless, I think that we must know how to take breaks to be more productive in front of the blank sheet …”

And remember, as one of Brian’s Oblique Strategies puts it, “Withdrawing in disgust is not the same thing as apathy.”

Additional research by Ella Lee.