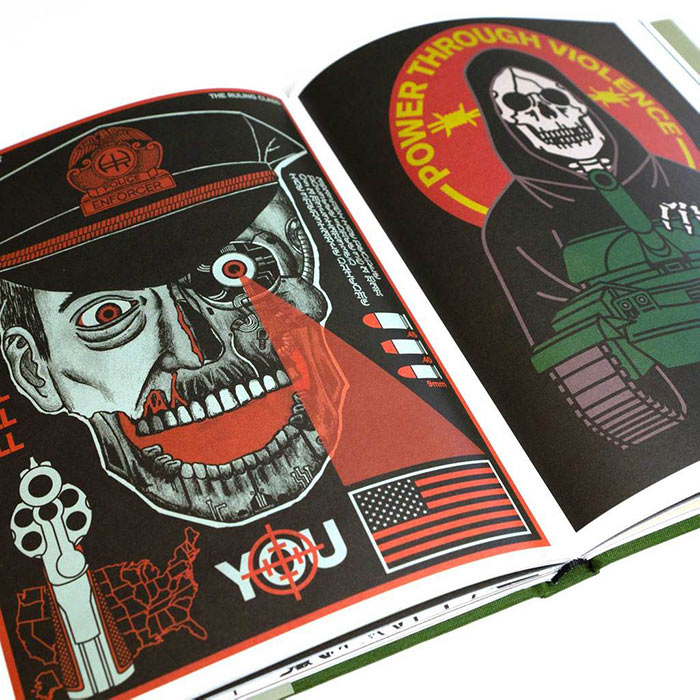

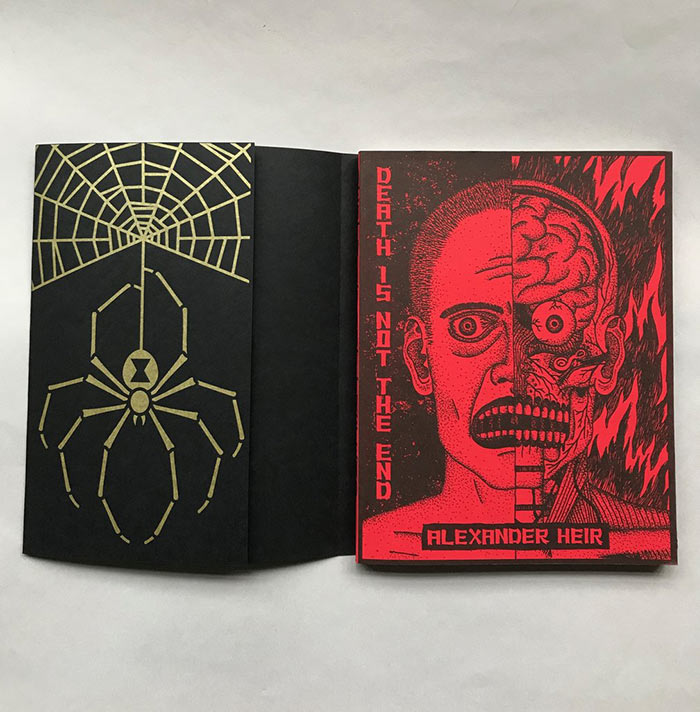

Few artists have shaped the visual language of contemporary underground punk and hardcore as much as Alexander Heir. His designs have featured on album covers on vanguard DIY labels like Static Shock and Toxic State Records (where he’s also released his own music, as frontman of industrial outfit L.O.T.I.O.N.), and he’s designed gig posters and flyers for underground artists from all over the globe. He’s also owner and proprietor of the much-loved Death/Traitors clothing brand, which of course sports his instantly recognizable visual style—graphic, intentionally schematic, drawing influence from classic punk illustration, Japanese ukiyo-e art, Russian tattoo culture, and more.

We recently chatted with Alexander about his latest book collection of artwork, WARRR2K∞//Work 2015-17, which was issued last year by influential independent record label Sacred Bones; his love of Ghanaian movie poster art; and being the only punk illustrator we know who’s designed kite art.

Can you describe your aesthetic a little bit and what informs it? There’s obviously the punk/DIY influence and the occult shows up, but it’s deeper than that.

Obviously my work is very rooted in the underground DIY punk world; that’s where I first started making work. But one of my major influences is Japanese woodblock prints, which has also influenced a lot of tattoo culture. Like you said, the occult and the esoteric—the underground from multiple places and eras throughout history. As you grow as an artist and try new things, little things you discover spark your interest, like Japanese woodblocks, and I’m very much into Ghanaian movie poster paintings right now, as well as more sci-fi, cyberpunk, futuristic stuff—weird ’70s and ’80s sci-fi stuff, too. I think it’s important that as you grow your style, you also expand your influences. The more breadth of knowledge you have about art history, the more you can incorporate it into [your work]. I think that’s what having a quote-unquote unique style really is: instead of aping one person’s hand, you take what you like but also draw from elsewhere, and mix it up. Then all the sudden you’ve got a new thing happening.

That’s funny you mention Ghanaian movie posters. I never made that connection before, but now that you mention it, it makes total sense.

That was a funny thing because I had started to paint in a similar style then discovered the posters after a couple of years. I was like, “Whoa, this is amazing,” but it kind of looked like what I was doing anyway—I don’t want to say crude, but graphic and simple paintings. So I was really attracted to that.

There’s a great gallery here in Chicago called Deadly Prey that’s devoted to Ghanaian movie poster art. Definitely check it out if you ever find yourself in Chicago.

They actually had a show out here [in New York] I went to that was great!

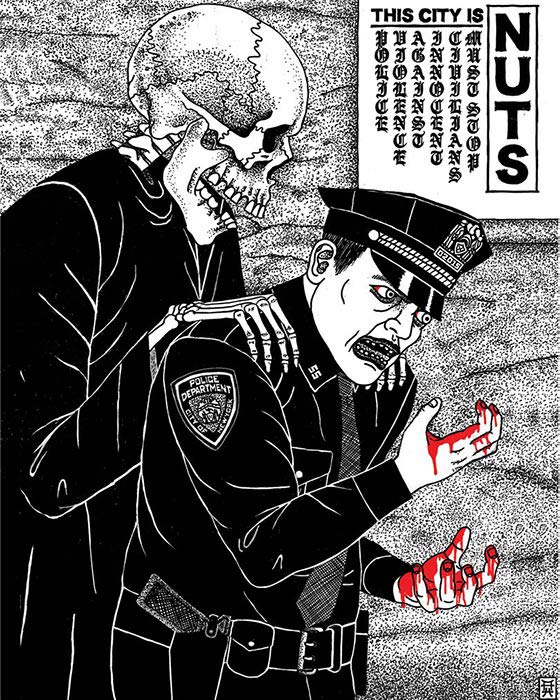

- Alexander’s cover for the ‘Nuts’ fanzine, included in the ‘WARRR2K∞//Work 2015-17’ collection. COURTESY OF SACRED BONES.

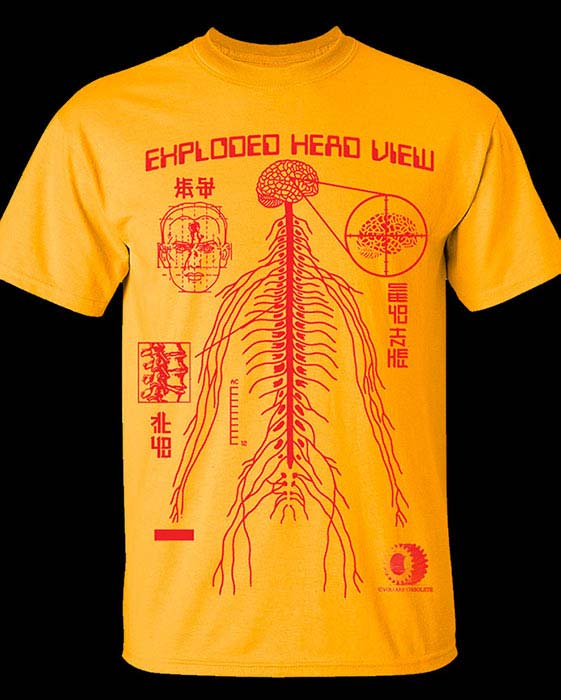

- Alexander’s Exploded Head View shirt design, from his Death/Traitors clothing line. COURTESY OF ALEXANDER HEIR.

Violence—or the threat of violence—looms in a lot of your illustrations. But there’s clearly a social conscience, too, whether it’s anti-police misconduct or anti-war or some other concept.

Absolutely. The work can be purposefully over the top and in your face, but it does have at least some sort of message to it. I kind of look at the shirt design almost as propaganda—someone’s wearing an image on a shirt; you’ve only got a couple seconds for someone to notice and understand it. So sometimes the bolder the better. You can have a crazy-violent, over-the-top image, but it’s actually referring to anti-war or something like that. And, yeah, as an artist and as a punk, especially, it was important to make work about the times we’re living in. You put a vibe into the world particularly with fashion. When someone’s going out into the world, hundreds of people are going to see that shirt. So what is that thing you actually want to make people feel?

Is it challenging to ethically source the clothing you need to run your fashion line?

Everything that’s screen-printed I do myself. I try to get shirts as much as I can that are made in the U.S. Even still, maybe the shirts are being produced in the U.S. with fair labor laws, but where does that cotton come from? Where is it being dyed? The supply chain makes it almost impossible to be perfect. Or the companies that do have to charge 40 dollars for a shirt because that’s just how much it costs. That being said, I try to be aware of everything. I’m in touch with the manufacturers, and what I do is small scale. The way the global industry’s set up, it’s almost impossible to have something totally ethically done.

The power of the dollar is strong, so I don’t think you should totally shy away from consumer activism. But also, the idea that, as they say, there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism—even if you’re going to the most DIY indie coffee shop, at some point someone’s getting fucked over. But that can be defeatist. You can live somewhere in the middle, where you minimize harm while accepting that no one, including yourself, is perfect.

“There’s this idea that being creative is something you either have or you don’t, which is not true at all. So much of it is about practice and sitting down and doing your homework.”

Do you approach things differently when you’re working on show flyers and album art versus your own paintings and illustrations?

For sure. Obviously when you’re working with someone else you have to consider their vision—that’s the primary thing. I think designers are problem solvers, so before I’m putting my pencil down, I’m thinking about the band, what does the album title mean, can I encapsulate that? So there’s always a musical component or band informing that. Whereas if I’m making my own art, there’s no limits. Sometimes that’s cool because it’s all up to you, but oftentimes it’s actually useful to have someone who’s already started a little spark you can build off. If someone hires me to do an illustration, it’s based on work they’ve seen, so they obviously want something that looks similar to what I’ve done before. But if it’s for myself I can push new things, experiment, fail, and try new things.

When I first saw the Warthog cover art, I thought it looked like your aesthetic, but a little different at the same time.

That was great. Those guys are friends of mine and we wanted to work together to push something new. I had been working in color more but hadn’t done an album in that style, so that was a good challenge for me. Every new project you level up and learn something new. You force yourself to be on your toes. “I gotta do another album cover; I can’t just do another skull.” Or if I’m gonna do a skull, how am I gonna make it stand out from the last dozen?

Alexander designed the cover art for Warthog’s self-titled 2018 EP. COURTESY OF STATIC SHOCK RECORDS.

Are you able to make a living solely on illustration and clothing?

I live off the clothing brand. The day-to-day is spent, depending on deadlines, filling orders. Or if I have an art deadline, I’ll spend the week focusing on that. But for the most part, I live off fashion. I’m lucky enough to want to make shirts in the first place, and that happened to be something that was actually feasible.

I graduated from Pratt in 2006. Then I started doing printing for hire, printing shirts for other people while doing my brand on the side. Slowly, as Death/Traitors kicked up, I was able to focus on myself. It took about five to seven years.

Was that nerve-wracking or liberating, making the jump to solely working for yourself?

It was more nerve-racking when I first started out. Those were the lean times, when rent was late, and I was figuring out how to live and juggle a business. That was definitely pretty stressful and difficult. By the time I went to just Death/Traitors, I had everything set up. I probably could have even stopped printing the year before that, but I wanted to make sure I was totally good. Now, thankfully, it’s a pretty self-operating machine. I can just post things on my web store, take care of printing and shipping once or twice a week, then spend the rest of my time making new designs or doing whatever else needs to get done.

Read more illustration, fashion design, and book coverage at Sixtysix.

Your second compilation of illustrated work came out in 2018. There’s a reference to Raymond Pettibon on the jacket sticker, in terms of how your aesthetic stretches from that continuum. Have you had any conversations with any of the old punk-illustration legends?

I haven’t. It’s flattering to me. My work is out there; it’s going to resonate hand in hand within this punk context. Hopefully I will one day, but I don’t think I have the same cultural capital across the board that those people do. They’re cemented in time, real legends, from when punk was globally and culturally a new force. We’re continuing in that tradition, and what we’re doing is important, but I don’t know that it has the same cultural impact or new energy per se. I hope to get there, but I don’t know if it’s even going to be tied to punk per se. Or maybe it is, but we can redefine that in our own terms and not be just limited to comparisons of the ’80s.

Alexander Heir. PHOTOGRAPHY BY OLIVIA MCCAUSLAND.

You’re kind of doing that now whenever you branch out beyond strictly music-related work.

Exactly. Culturally, this is such a weird time, where the underground and mainstream are kind of mish-mashed, especially with the internet, for better and worse. We’re almost at this weird cultural end zone where it’s going to be interesting to see in the next 20 or 30 years what happens. Is there going be a new anything? Art, music, whatever. Or is it all kind of rehashing or redoing stuff from the past century?

I never got a chance to talk to the older heads. If I could just sit down and watch them draw it would be pretty amazing. But also those old heads came from such a different time, I don’t know what advice they could give beyond the technical. My generation is this no man’s land trying to navigate a fucked up economy and the unaffordable New York real estate, and existing in these weird websites.

On the one hand, I can live off it. I’ve been doing this for 10 years and worked my name up to a point where it’s somewhat recognizable. But it’s still a struggle, being in this middle ground that’s hard to break free from, as a business or an artist, and not feel like your tied down to just making ends meet. Obviously there are so many people who are worse off, but the modern age is not friendly to artists. In ’80s or ’90s New York, me and my friends could’ve had big studios and our own stores selling our stuff. Now the idea of having a storefront is ridiculous. I share a screen-printing spot with four friends where every square inch is maxed out to make it work. That’s what you gotta do when you hustle, but it doesn’t need to be like that.

Alexander’s first collection of artwork, ‘Death Is Not the End: The Work of Alexander Heir, was released by Sacred Bones records. COURTESY OF SACRED BONES.

Are you feeling the squeeze at all in terms of New York City real estate prices?

My apartment is rent-stabilized. But in the bigger picture, if nothing changes, culture is going to be destroyed. No one young can afford to move here. Everyone loves to complain about how much New York has changed, but it’s still the only place I can imagine living. But it could be so much more vibrant if the city was a little less hostile to people without money. The city incentivizes landlords to charge a ton of rent that leaves storefronts open—and the Lower East Side, one of the most desirable areas in the world, ends up full of empty storefronts.

You’re probably the only punk illustrator I know who has designed artwork for a kite. What inspired that?

Since I was a kid, I always loved flying kites. I used to fly them with my dad on the Jersey Shore. And then, getting older, hanging out at roof parties. I’d grab kites at the dollar store and actually turned a few friends on to it. It’s really zen. It was something I wanted to do for so long, so when the second book came out, I was like, let’s do it. There’s also the Japanese tradition of kites as well, which are handmade and much more intense, but there’s still that tradition of art on kites, so it makes total sense.

Alexander celebrated the release of his second collection with limited edition clothing, pins, and patches—and this kite. COURTESY OF SACRED BONES.

How do you work? Do you have any consistent work habits you swear by?

In general, I like to let my brain warm up in the morning. I deal in e-commerce, so a lot of emails, then I go into more creative stuff. The most important thing I’ve learned is, sometimes I really need to draw, and it’s just not working, but other times I’m really in the zone—as an artist you need to accept both those things. Obviously a deadline is a deadline, and there’s a lot to be said for working through a slump. But if you’re just staring at a page and it’s not working, just get up and do something else. Or vice versa. If you’re in the zone and that magic is happening, just go for it and fuck everything else off. I’ve definitely cancelled going out or stayed in all weekend because I felt like really good in the studio. You have to embrace that.

There’s this idea that being creative is something you either have or you don’t, which is not true at all. So much of it is about practice and sitting down and doing your homework—but there is that little bit of spark that sometimes is just not there, and you have to coax it out somehow.

Do you have anything else coming up in 2019?

Yeah, L.O.T.I.O.N.’s second LP is coming out April 19 on Toxic State Records, and we’re having a release show at Trans-Pecos, in New York. So I’m stoked for that. And I have a whole new line of Death/Traitors stuff coming next month as well.