Luca Nichetto founded his multidisciplinary design practice, Nichetto Studio, in Venice, Italy, in 2006, specializing in industrial product design and consulting. Throughout his career Luca has worked with Cassina, Foscarini, Hermès, and many more. Today his studio serves global clients across all design disciplines, renowned for its expertise in industrial and craft manufacturing, cultural references, and attention to detail.

Theresa Marx is a photographer and cofounder of the European design studio Project 213A. Her photography, characterized by its intimate and expressive style, complements her role at Project 213A, where she collaborates on creating furniture and home accessories with a focus on sustainability and traditional craftsmanship.

Here the two designers meet for the first time to discuss their work, as Luca begins their conversation sharing the path that led to his career. —Gianna Annunzio

- Luca Nichetto’s Afloat chandelier for Lladró. “For me, seeing a drawing become an object was like going to buy a piece of bread—there wasn’t a big difference.” Courtesy of Nichetto Studio

- Luca’s Airbloom table lamp for Lladró. Courtesy of Nichetto Studio

Luca Nichetto: I think back to when I started. I was quite lucky; I didn’t decide to become a designer. It was something natural because I was quite good at drawing when I was a child. My parents allowed me to study at the Art Institute of Venice. During the summer my classmates and I would knock on the doors of different factories in Murano to sell our drawings.

Theresa Marx: Was that your idea, or was the school pushing you?

Luca: It was our idea. We had a folder full of drawings. Drawing and being able to make some money to have fun during the summertime with my friends was a necessity. They were easy things to do.

As I was deciding what to study at university, I discovered there was a new industrial design facility in Venice. I decided to give it a shot, and I maintained the ritual of knocking on the door of the factories during that time.

I’m from Murano, a little island with 4,000 people living there, and 99% of the people are involved with the glass industry.

For me, seeing a drawing become an object was like going to buy a piece of bread—there wasn’t a big difference. My grandfather was a glassblower, and my other grandfather made chandeliers. My mom decorated glass.

- The Mirror lounge chair from Project 213A has a brutal and minimal shape. “We started Project 213A in lockdown on Zoom,” Theresa says. Courtesy of Project 213A

- “Social media culture is so instant,” Theresa says. “You can keep scrolling and scrolling. If I plan a photo shoot or our next Instagram post, we always need to be aware of this. We’re terrified of being lost in the algorithm.” Above, the Porto Sofa courtesy of Project 213A

What I can see now after 20 years of doing this job, what the Murano glass industry taught me from day one—even when I was knocking on doors—is the importance of building a relationship. You need to be able to build relationships with people who are there to make your idea become a real thing, especially if you are in front of a 1,000-degree oven to create the object.

You need to find a way for a master glassblower to interpret your ideas. You need to build a team in that moment, and your decision-making process needs to be quick.

The shape of glass can change in a second. You need to understand when the right moment is to tell them to stop or try a little more—to respect the people who are doing the best they can to interpret your idea, plus respect the nature of the material.

Being fast in making decisions and accepting compromise is something I still use every day, even when I’m designing with other materials and product typologies.

And for you?

- In April, Kerakoll unveiled Huetopia – Scenarios in Colour, an installation by Nichetto Studio that uses colors and surfaces to portray an imaginary place. Photo by Salva Lopez

- Inside the Huetopia exhibit. Photo by Salva Lopez

Theresa: I have two other business partners in Project 213A; Jurgita Dileviciute is based in Portugal, she’s a footwear designer, and the other, Clement Deboeuf, is based in Paris. He has a background in cinema. We started all of this in lockdown on Zoom.

There was a moment I thought was really sweet when we started. Our idea was to focus on smaller items like vases so we could create a stock and then get into shops to get our name out there. When we showed up at the ceramic factory for the first time, we realized it was huge. They had all these people and massive kilns—sometimes even bigger than a London bedroom. We felt like we were on the best playground the world had to offer. The owner of the factory took a liking to us. I think he was like, “Those crazy girls, what are they thinking? They’re coming here with their weird designs.”

We created the shapes with him. We were really hands-on, and then we made molds from that. When we gave him the first drawing it came back perfect, but it wasn’t what we wanted. There needed to be character. I think on the fifth design he did for us he said, “Look, I’ve made it a bit irregular!” It was nice to see that he understood what we were after, and that we wanted to look different than products he does for other clients.

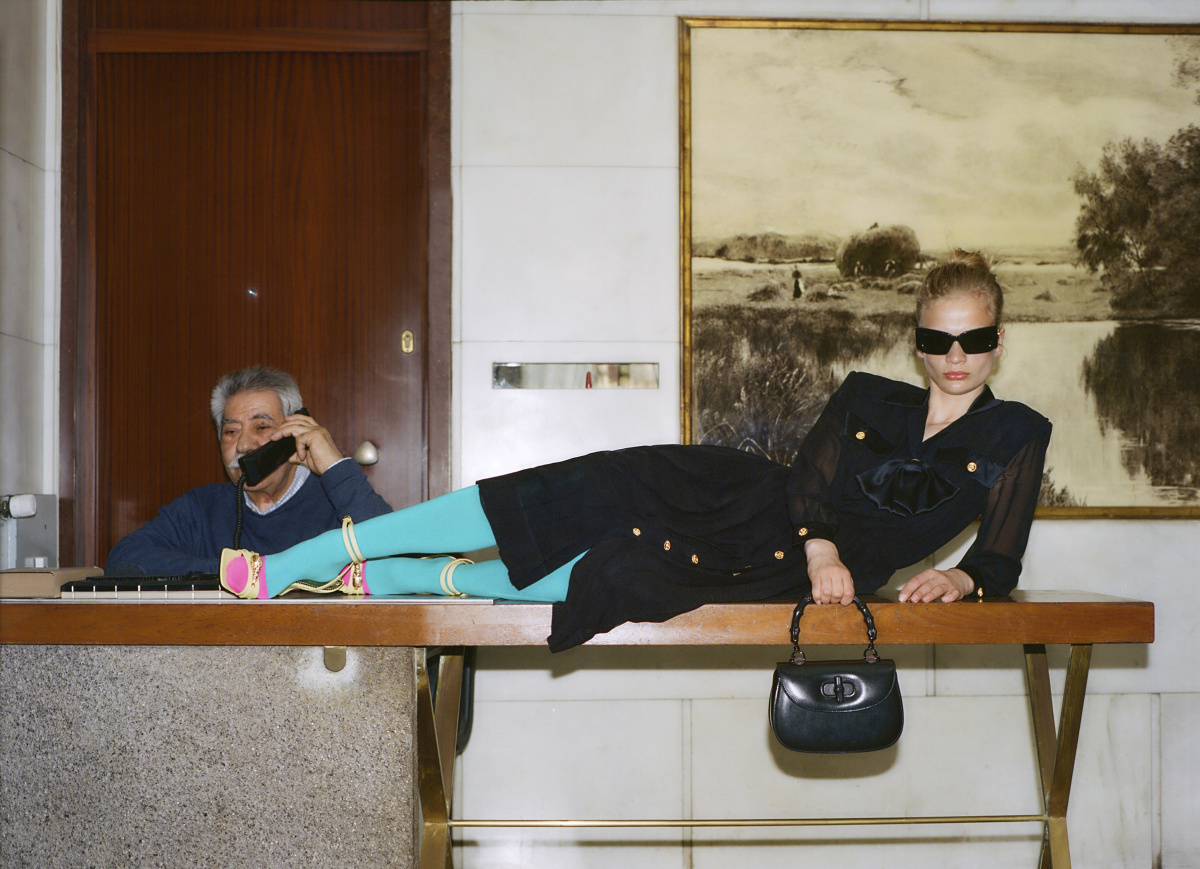

- Theresa’s photography, characterized by its intimate and expressive style, complements her role at Project 213A. Above, Theresa Marx for CR Fashion Book

- Theresa Marx for CAP 74024 magazine

Luca: When I was younger I had the chance to spend a couple of days with artist Enzo Mari. He came to Venice to visit the Biennale. I was just starting out; I think I opened my studio two years prior.

There was a curator from Milan, a good friend Beppe Finessi, who loved to introduce the old masters to the younger generation. We had the chance to spend time together. I remember one thing Enzo told me. He said, “You need to think that every time you’re designing something, you’re building community. You might not meet everybody in this community, but thanks to your idea, people will have a job and invest their time to support your creativity in many ways.”

Now there is this weird idea where everybody wants to have everything quick. They’re about not investing time. Even with online shopping—you see something, you buy it, and you have it at home.

“The shape of glass can change in a second. You need to to respect the people who are doing the best they can to interpret your idea.”

We’re losing that precious feeling of when there’s something done a certain way you need to wait. Not losing time by waiting but waiting because people care, and it’s well made. I’m living in the country of IKEA and H&M, so they teach the opposite. From my perspective that’s completely against the idea of educating people to understand the value of craft.

There is a market, of course, for custom product, but that is almost a target demographic that rejects being part of a mass production system. They have enough money that they can customize their own things.

I just came back from ICFF, and I love what Claire and Odile, the two French women who are running the show, are trying to do. But for me it was not a design fair. It was a craft fair. There was craft everywhere. We need to understand the difference between design and craft, and if they can go together or not.

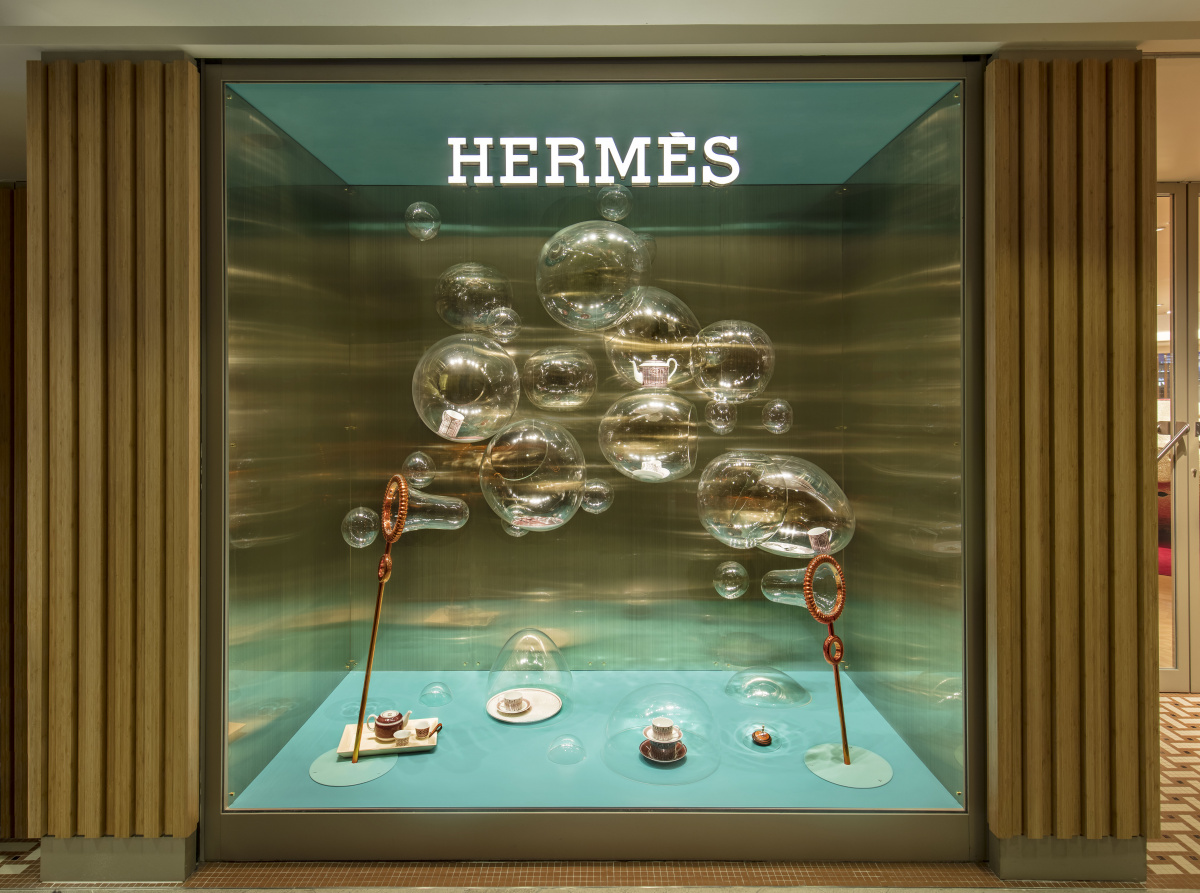

Elongated bubble sticks give shape to a flock of glass water bubbles, featured in the Hermès boutique in Hong Kong. Courtesy of Nichetto Studio

Theresa: When it comes to the smaller companies who start something like this I see that very often, and I think it’s also something I see in fashion. They influence the bigger ones.

With your IKEA example, I understand its mass produced. Do you know the classic shelf they have? It has a lot of squares inside and some people use it as a room divider. I had one I bought secondhand for my studio a few years ago, and then I wanted to get another one. When I received it, it was slightly different dimensions.

I didn’t understand why, because it’s a classic; it’s always been around. Then I found this article that said IKEA decided to make that specific product reduced by around 5 millimeters, and it saved a crazy amount of wood and CO2 emissions. I was really proud of IKEA. They got my thumbs up on that.

Luca: If they want to be sustainable they need to shut down their business. That is the reality. If they’re talking so much about sustainability, they need to reinvent their business model. I think there is a layer of hypocrisy. Without being so mean to IKEA, or other bigger companies like that, they are providing what people desire, so the problem is not only on them. The problem is on us.

I remember when I was a child speaking with people around 50 years old. Their curiosity to learn and their know-how was much higher than it is today. They were respected for their knowledge. Right now there is no form of that respect because, in the end, older people like me don’t have that knowledge.

Theresa hopes to eventually reach a point where she is paid for her editorial work. “They’ll give me a budget because they believe in what I’ve done.” Photo by Theresa Marx

We can find any information we want in a much shorter time. We’ve become so spoiled and arrogant that we seek and receive without really learning. I’m generalizing now, but in the end there’s a reflection of that in what the customer is buying from us. We need to find a way to trigger their curiosity.

We are in this interesting situation where design reflects society. Sometimes design can be pioneering and show where society should go—at least when design was political in the ’60s and the ’70s. But it’s not anymore. There is no more artist utopia to idealize so strongly you can move in that direction. Everything has become a little bit cosmetic.

Theresa: Social media culture is so instant. You can keep scrolling and scrolling. If I plan a photo shoot or our next Instagram post, we always need to be aware of this. We’re terrified of being lost in the algorithm. We’ll work so hard on a product and put money and effort into photographing it. You put a little bit of yourself into it, you’re proud of your work.

Then you get 10 likes and you automatically think it’s not good. But then I also think, “Let’s be stubborn. Keep on posting it.’ In the end someone will like it—if they see it. I speak with a lot of people about this, and everybody seems to have the same opinion.

Luca: It makes sense. You’re scared of the algorithm, but at the same time talking about educating customers. At this point we shouldn’t even use the word “customer.” It would be better to use the word “users.”

The Troag LED suspension lamp by Luca Nichetto for Foscarini displays linear, suspended lines that emanate a sense of natural familiarity. Courtesy of Nichetto Studio

Theresa: That’s the other thing. The moment you have a customer, they already like your product. It’s more about making people aware of the fact that you even exist.

Luca: Exactly. I think you also need to be good at receiving a “no” from the other side. Even something like Tinder is totally a window on our society. That app is taking out all the insecurity you need to have when you are approaching something unknown, finding your creativity to approach that unknown, and being ready to receive a “no.”

Now you’re just swiping back and forth—you like or you don’t like, in three seconds. Those things make everybody untrained to build relationships of any kind. The perception of what we’re doing as designers has completely changed along with it.

Theresa: It’s a new time. In the photography world there’s this huge fear AI is going to take over. I personally don’t have this fear because I feel people need to start seeing it for what it is. It’s a tool, and it can only be as good as the person using it. The only way it could replace me is because I haven’t used it right. I might not necessarily be the person physically doing it, but it was my idea.

When I went to university I needed to save money to photocopy books in the library. These days there are photos available of everything online. A friend of mine who is a tutor recently showed me one of his student’s sketchbooks. It was a completely different thing than when I went to university. I cut out everything and drew over my photocopies, which is cool and good, but it was very of “that time.”

“Putting a little bit of extra effort into something always works.”

I also know certain values don’t necessarily disappear. At my university there were categories like secondary and first research. First research would be seeing someone on a cool bike, and you get inspired to do a bike. Maybe you start drawing it and taking pictures of it. The secondary research would be thinking, “What’s the concept behind it? How can I push this? Can I draw the bike with three wheels?”

If that’s good, and if you’ve done your proper homework, it will be a new and interesting product. If you manage to find a tool to communicate what you want to do, be it AI, be it old-school fashion drawing, it’s just a part of progress.

Luca: In the past they used to say if you are a very strong talent, you will pop up anyway. I’m not sure about that anymore. The quality of the output is so high, and the decision-makers are so low in their know-how, it’s very complicated to discover talent.

If we’re talking about the geniuses, they don’t need anything. They will pop up regardless. But if we’re talking about the good ones, the talented ones in this huge pot, I think coming up will be quite tough. You need to do very good PR for yourself. Things in the past that you didn’t need to have, you now need to have.

“You need to prove yourself nonstop,” Theresa says. “It seems like it’s on a different scale, commercial and editorial work.” Above, Theresa Marx for Blanc magazine

Theresa: I think I slightly disagree. I read something that said, “The successful artist we know is the artist that knows how to market himself.” If you look back, Picasso was amazing. But why? Because he was a flamboyant man who lived the way he did.

That was part of marketing back in the day. A lot of female designers who worked for highly celebrated designers are now starting to pop up as we look back at their talents. Nowadays the doors are more open to everyone. But still, you have to market yourself to get where you want to be.

Luca: For sure, but if Picasso was not a good painter—even if he was able to market himself—he would never succeed. While art directing at some companies I review the proposals of other colleagues who are quite well-known. Sometimes I ask myself how a person is so famous for the quality of the job they provide because I was on the other side.

The company I’m working for on that specific project says, “Yeah, but he’s famous. We need to produce it anyway.” Why do we need to produce for someone famous when there’s this young fella that is completely unknown, with a better proposal? I think there’s still a lot of confusion on how to discover the right talent.

“In the design industry they’re pushing to launch products at the same speed as fashion,” Luca says. “They don’t understand that if you’re doing that you’re killing the market.” Above, the Twenty-Five dining table by De La Espada Atelier and the Sela dining armchair by Luca Nichetto. Photo by Sanda Vuckovic

In the design industry they’re also pushing to launch products at the same speed as fashion. They don’t understand that if you’re doing that you’re killing the market. I’m not saying everything is bad. It’s also an incredible time to jump out of a crisis with brilliant ideas.

Normally when there is crisis you need to be even more creative to jump out. I hope in this moment there will be someone coming out with a cool, interesting idea that can be revolutionary in moving up.

Theresa: I could go down a rabbit hole of why certain things are becoming more and more unfair. The structure of how certain universities function feels more like a factory of trying to get people on board to get fees. It isn’t necessarily a question of how much talent is behind them, it’s just because they’re a well-paying student.

Luca: I think that’s the main problem. I’ve had that experience teaching at my former university in Italy and doing workshops in universities all around Europe and the US. It’s pretty clear that most of the students are rich in a way.

The scholarships they offer to talented students are very few compared to the ones who are paying. This creates a crazy number of people who think it’s easy to jump into the market and start running their business later on.

Theresa: There were a few people I graduated with who I felt drowned. They were mega talented but didn’t have the tools, or the right situation, or the support of someone believing in them and pulling funding together to get something beautiful going. The market is oversaturated as well. When I graduated I think there was one position for 100 students. Hence I became a photographer outside of my career.

“Our idea was to focus on smaller items so we could create a stock, and then get into shops to get our name out there,” says Theresa. Above, dining table courtesy of Project 213A

Luca: It’s like that, right? When I graduated in design, everybody in Italy would say if I wanted to be a designer I needed to move to Milan. I would say, “I don’t want to move to Milan. I don’t like it. Why do I need to go there?” I decided to open my studio in Venice instead, and I was probably the only designer there.

I became kind of exotic for the Italian design community, because 90% is based in Milan. It allowed me to be a little bit more special just because I hate Milan.

Theresa: That’s exactly what I meant when I mentioned creating your own language. Just because people tell you must go to Milan, it’s a recipe. Who says you have to follow this recipe to be successful? If an opportunity arises and it feels right, just take it. As long as it sits within your gut, and it works.

Luca: I think AI will be a tool that will clean up a lot of mediocrities. Only the followers will use that. The ones who are self-confident, as you say, who see it as a tool and are empowered by it creatively don’t need to be fearful.

Theresa: It’s about having original ideas. Someone recently asked us where we get our inspiration. It’s a weird question to answer because I’m like, “Just look around you, it’s there.” We recently did a ceramic side table based on this soap that had the most beautiful shape. The more you use it the more it takes on a different shape.

- “When they ask where inspiration comes from, even I don’t know sometimes,” Luca says. “I think we are collecting info and data as a hard disk in our brains.” Above, Jeometrica furnishing system by Luca Nichetto for Scavolini, courtesy of Nichetto Studio

- From the open-fronted base unit to the shelves, every component offers options for a beautiful, colorful, and functional kitchen. Above, Jeometrica furnishing system by Luca Nichetto for Scavolini, courtesy of Nichetto Studio

You need to dare a little bit, not just do easy research sitting on your phone. Maybe even go to the library. I like to pick out books that are not part of the subject I work in. Inspiration can be everywhere. The most beautiful thing is when you’re on holiday because your mind is in a different place.

Luca: That’s true. The problem is the holiday is not a holiday anymore because you start to work again.

Theresa: I always dream of having a long holiday, and I know for fact after day one I’ll get bored. But it’s a different way of working because you allow yourself to fall into a pattern of learning. I enjoy it.

Luca: For me, when they ask where inspiration comes from, even I don’t know sometimes. I think we are collecting info and data as a hard disk in our brains. You collect things, you watch a movie, read a book, you see a person walking on the street. Then there is a trigger in an action, or in a food or in a smell or in a book. Somehow, all the pieces of the puzzle start to come together. I start digging until I find it.

On my side, most of the time it’s client content. They’ll say they’re looking for a new sofa or something; there is a very specific brief we try to accomplish. If I did exactly what the company asked me the project would be wrong. What they asked me for doesn’t exist. The only way to do it is to take about 20% out of the brief.

- “When it comes to smaller companies, I see that very often, they influence the bigger ones,” Theresa says. “I think it’s also something I see in fashion.” Above, Theresa Marx for Vogue Hong Kong

- Theresa Marx for Vogue Hong Kong

Theresa: And giving options. I notice these days if there is something I personally believe in, I need to give an option that’s worse so they can see what I had in mind is better.

Luca: It’s a Le Corbusier strategy to do that! Did you know that?

Theresa: I thought it was a Theresa Marx original!

Luca: When he was commissioned to design something, Le Corbusier always arrived with two options. One was the one he really liked—the model was perfect. The other one, the one the client asked for, was well done but nothing special. Every time they saw the one he liked, they thought it was the best. The real brief was the other option.

Theresa: Putting a little bit of extra effort into something always works.

Luca: For sure. If you only deliver what people expect, you get bored. Sometimes what people are reading about your practice is not what you want to be anymore. I believe it’s nice to jump out of that comfort. Maybe a company will tell you “no,” but at least you’re doing something you want.

Theresa: I struggle with that, especially in photography. There’s this concept of editorial work and commercial work. Usually you get booked for commercial work because you’ve done the editorial work, but the editorial work is the one you have to put your money and time into. You have to almost force people to give you the commissioning letter for a magazine, to get your idea across, to then get the commercial work.

- “I notice these days if there is something I personally believe in, I need to give an option that’s worse so they can see what I had in mind is better,” Theresa says. Above, “A Closer Look” by Theresa Marx.

- Theresa Marx for Manifesto magazine

Luca: When I was in New York I was talking with a designer about my business model. I explained it, and they noted I was mostly doing commercial design. I thought, “What do you mean ‘commercial design?’” They said it’s when someone commissions you for a product, you design it, and they sell it for you.

I said I’m sorry, but every single form of design should be commercial—otherwise it’s not design. It was quite funny for me that they defined it that way. They were putting artistic and commercial design on two different levels.

Theresa: At the end of the day, if I do a commercial job, it’s to sell a product. There are more people involved who have an opinion—like the sales team telling me it needs to look a certain way so the customer will understand the product. My creativity is gone, but that’s fine. I can still click the button, no problem.

One day—still my big dream—I’ll have reached the point where I get paid for editorial work. They’ll give me a budget because they believe in what I’ve done. You need to prove yourself nonstop in order to get there. It just seems like it’s on a different scale, commercial and editorial.

Luca: The point is that it’s not even true. If I’m working with a glassblower in Murano, even a famous brand like Venini, how many of my vases can they do per year? 30? 40? No more than that. Is it commercial design, or editorial design? For me it’s almost editorial design. It depends on the nature of the company.

Theresa: And it’s down to the opinion of the person viewing it.

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 12.