I spent a day with Yinka Ilori in our Chicago studio. He was on a brief visit from his home in London to oversee a collaboration with Momentum Textiles & Wallcoverings and do a technical run-through of a prominent public art piece.

To be transparent, I was skeptical of his work. Maybe it’s my East Coast upbringing, the countless hours I spent in grimy punk clubs, or the formal walls of art academia I later fumbled through, but one thing I’ve come to think of as truth is that a black wardrobe is serious, but color is frivolous; it’s the choice of children and clowns or, in the worst case use, hippies (the cultural enemy of my youth).

So when the idea was presented that I spend the day writing about Yinka, the designer known for explicitly using bold colors and patterns—the designer with a new pattern titled “Shower Me With Flowers,” I was reluctant.

I was, of course, very familiar with his work which includes a successful mix of products, public installations, museum exhibitions, and artwork. I figured I should do it; I should learn a little something. When he arrived at the studio we took some photos, we ate some sandwiches. I drank an Arnold Palmer. (Do they have those in London? I forgot to ask.) I asked him about his work, his life, about the North London neighborhood he grew up in, about his Nigerian family, his studio, his young family—and I listened. Slowly, his optimism and sincerity broke me. I began to see the work through his eyes, and I liked what I saw. Here’s some of what he told me.

—Chris Force

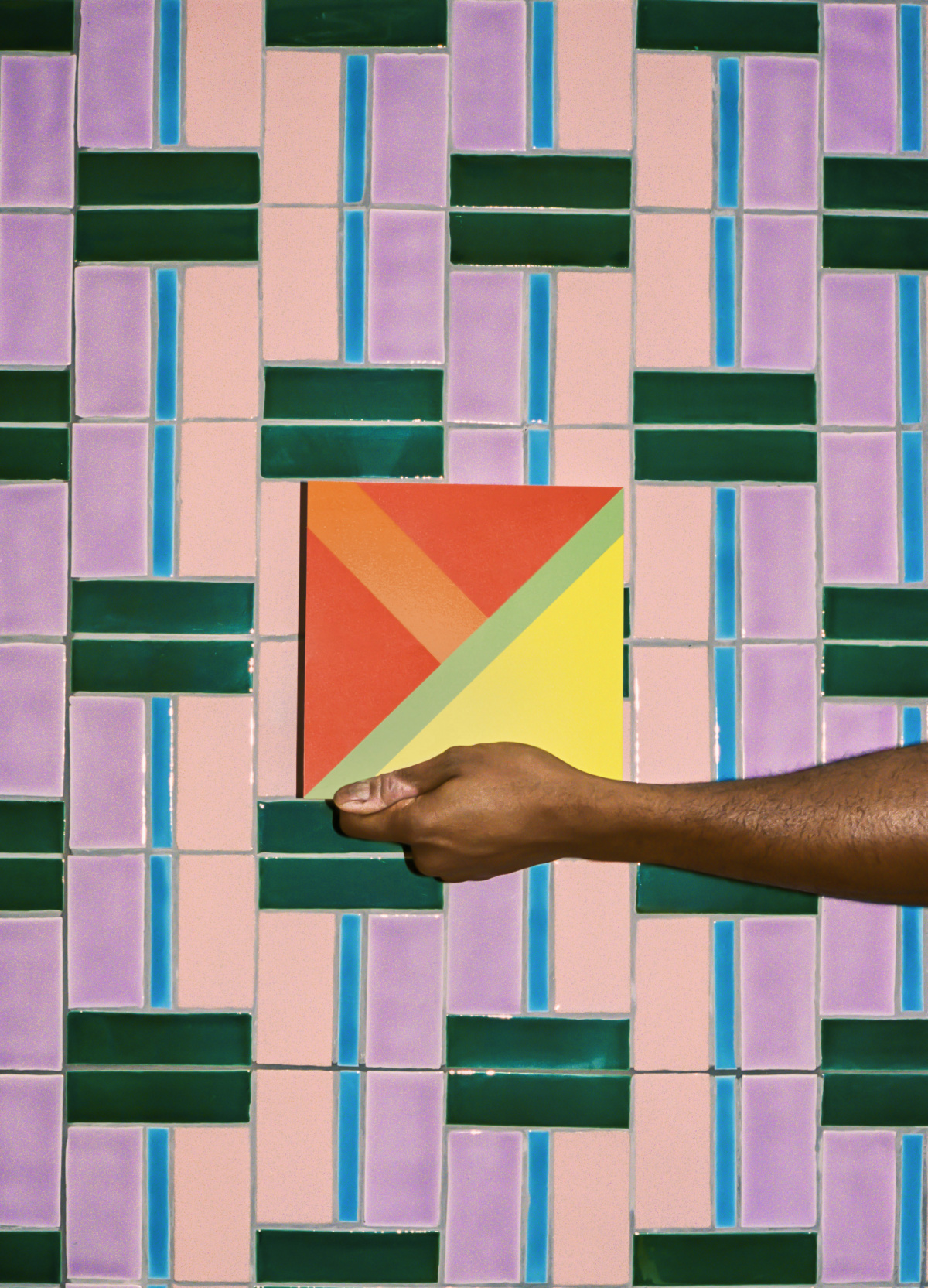

Yinka Ilori surrounded by his collection for Momentum Textiles & Wallcoverings. “This collection for Momentum was all about affirmation and was inspired by dream catchers. In my culture dream catchers might seem a bit strange, even demonic. But for me they symbolize catching dreams and positive affirmations,” he says. Photo by Chris Force

North Londoners often have a cockney accent. A bunch of creatives blossomed from that area as well, from musicians to actors to artists to football players.

I studied design for three years, and before then I studied fine art. Eventually I went on to intern for designer Lee Broom for five months. He was the only one crossing between art, sculpture, and design at the time. He did this curve-shaped table, and underneath it was a Persian rug. It was beautiful.

Initially I couldn’t see myself anywhere within the design industry. Once you go to art or design school you’re introduced to the Francis Bacons—who were great, incredible artists, but I couldn’t connect to the themes within their work. I couldn’t see me.

We were learning about old masters who didn’t grow up in London or between two cultures with immigrant parents like I did. With design I want to connect with the story. I want to find myself expressed within those things and ideas. That’s the reason I decided to go to Nigeria.

I had only been to Nigeria for two weeks when I was 11 and again with my family after university. My parents were always strict about reminding me I was Black and British—that although I lived in the UK, I was still Nigerian. They wanted me to maintain those traditional values and not dilute them because we lived in Western society.

Commissioned by the LEGO Group, the “Launderette of Dreams” is an interactive art installation and play space inspired by the creative optimism and resilience of children. Photo by Mark Cocksedge

My parents left Nigeria hoping it would give them satisfaction and a better life for their kids. What else can you lose when you’ve given up everything? They put their own dreams on hold to rebuild somewhere else. My parents have been in London for over 40 years, and they’ve never forgotten their roots.

We would watch Nigerian movies as a family, wear Nigerian clothes, go to Nigerian church service. I think that’s probably why I’m here today. I feel it’s given me my voice within this world I’m cultivating. I’m trying to push finding joy within design or art without seeking permission.

In Nigerian culture you often have to be a doctor, engineer, or scientist—something academic. Luckily my parents were very accepting of me wanting to be a designer. They came to my first graduate show where I designed a table for the French company Ligne Roset.

Even today they still come to all my shows and are proud of my collaborations and projects.

I was always obsessed with giving back to Nigeria because everything I’ve created—the colors, motifs—all come from there. In a way I felt I was stealing or borrowing without having lived there. I came upon some money from the British Council and had my first solo exhibition in Nigeria titled “This is Where it Started” in collaboration with Whitespace Gallery.

Nowadays it’s amazing to see the cultural exchange happening over there. There are musicians signing with big labels in Nigeria, and they host the Lagos Biennial. But back then I was one of the first people to do an exhibition in Nigeria with the British Council.

- Yinka’s collaboration with Momentum Textiles and Wallcoverings includes five distinct textile patterns and three playful wallcoverings. Courtesy of Momentum

- A chair from “Iya Ni Wura,” a bespoke collection created for the nonprofit Mothers2Mothers. Photo by Samuel Adjaye

I spent two weeks there diving into the culture with my family. I went to a few artistic studios, spoke to Nigerian artists, and met Nifemi Marcus-Bello. He was just beginning his career at the time. I feel there are a lot of eyes on Nigeria now—especially the music, architecture, fashion, and design. Now I go back and forth between London and Nigeria and I don’t feel like an imposter.

I love both of my cultures, and I want to celebrate both of those identities. There are so many things I’ve learned from being British and being Nigerian. My experiences are so different and personal. There’s resilience, hardship, and emotion within the work I create.

That’s why I always find myself in between art, design, and architecture. First and foremost I’m a storyteller—forget about art or design. That story might come in the form of a film or a chair or a tea towel or a mural.

The art world can often feel very closed off. I can’t stand gatekeepers—those people who set the rules and tell you what’s cool or what’s considered art. I found myself listening to those critics saying, “Is he an artist? Is he a designer? Is it a chair or a sculpture?”

I spent two or three years creating a body of work that wasn’t resonating with anyone. All the writers were asking, “What’s he doing?”

Around 2015 I decided I was either going to quit creating work or try one last time. It was make or break for me because I wasn’t making any money despite producing so much work and investing a lot. I created the project titled “If Chairs Could Talk,” where each chair was based on a person I went to school with.

“Filtered Rays” is Yinka’s first permanent installation in Berlin, Germany on the banks of the Spree in front of the Estrel Berlin Hotel in Neukölln. Photo by Linus Muellerschoen

That project changed my life. I wrote my own press release and spent weeks trying to find the right press contacts for editors.

Design Milk eventually featured the project on their Instagram page, and it went mad from there. That’s when I started getting knocks at the door from museums and galleries. Then Brighton Museum acquired a chair from that collection, which was crazy. Things just got better and better after taking control of my own narrative and destiny.

I studied product, so I had ideas for working within architecture and spatial design, but I couldn’t execute them. I couldn’t use CAD and only knew SketchUp to a basic level. I knew to grow and take on bigger commissions, I had to hire someone.

I ended up hiring a student architect from Lithuania who was with me for two years. We pitched for a project in 2021 to design an underpass in Battersea called “Happy Street.” That same year we won a competition to design “The Colour Palace,” a pavilion inspired by a Lagos market in Nigeria.

We beat architectural practices and big firms. Some architects can’t tell stories—that’s the last thing they think about.

Everything grew from there. I’ve been creating work for nearly 15 years, but the last 10 have just been pure hustle. I was super dedicated. I remember working 9-to-5 at Marks & Spencer, a food and clothing store in London, just to fund my studio.

All the money I made went into making chairs or tables, and then I’d try to sell them. During that time my friends were buying cars and traveling. I wanted to do that, too, but I always believed there was something greater out there for me. I didn’t know when, but I kept affirming I would have my own studio one day.

- In celebration of Frieze London and Black History Month, Yinka takes over George, a private members’ club, in London’s art gallery district. Photo by Kane Hulse

- The Yinka Ilori x Domus tile collection. Photo by Kane Hulse

You have to believe that small projects will open doors for bigger projects. That was my mentality at the time. I couldn’t travel much or live a luxurious life. There was always the risk of wondering if would ever happen, but I’ve always been strong-headed. I believed if you could dedicate your life to something, it should eventually pay off.

The last five years, I can say with my chest, I’m a fully functioning artist who pays people’s salaries. I can confidently say I’m the best at what I do. I’m a perfectionist when it comes to my work. If you put me in a room for 100 days I would produce millions of sketches and ideas.

It comes natural for me. If you give me a commission I’m going to give you the best—not a rush project. It’s coming from a place of love.

Growing up in London we had a playground in our estate that was terrible, but I loved the memories it gave me and the joy it brought. That playground taught me how to find joy, build a community, and respect one’s cultures. That’s why I relish designing for people in communities.

My work resonates with the West African community, especially the Nigerian community, because of the use of patterns like Ankara, which is a Dutch wax print made in Indonesia but worn by Nigerians. Growing up around these fabrics, using color and storytelling came natural to me.

Many artists and designers struggle with using color in their work—they don’t know how to use it. They put so much pressure into applying green and blue or pink and yellow.

“A Magical World” is an immersive forest showcasing the versatility of Yinka’s tile collection with Domus. Photo by Robin Gautier

My parents were rule-breakers. If they felt good in it, they were going to go to a party wearing pink and yellow. Maybe it looked mad, but they were going to own it. It gave them a sense of confidence and armor in a country where they experienced racism. I have a lot of respect for that fabric.

Textiles do that—people want to connect and talk to you about what you’re wearing. I became obsessed with that language, and it ran through into my work.

This collection for Momentum was all about affirmation and was inspired by dream catchers. In my culture dream catchers might seem a bit strange, even demonic. But for me they symbolize catching dreams and positive affirmations.

They inspired me to create art that opens space for affirmation. Colors aren’t just aesthetic; they can affect our mood and mindset. Green in a park, blue of the sea—these colors evoke feelings of peace and calm. Even a rose, with its pink or red, symbolizes love. Momentum was great to work with.

We initially had six or seven colorways, and then expanded into off-white. The different color variations allow people to choose the tones, or the softness of the colors, or the hues of orange and pink. I think there’s something in there for everyone.

Everyone we’ve worked with comes to me because they want joy. They want artwork that’s going to tell a story and take you on a journey. Now people recognize my style when they see my work. It took years to find my visual language, but over time it became a consistent theme. Having a style has also given me the opportunity to move into different spaces.

- “Beacon of Dreams” is an installation embedded in the natural landscape of England’s Soho Farmhouse. Photo by Gina Soden

- The piece offers visitors a moment of pause and reflection. Photo by Gina Soden

In my Nigerian culture, joy is love. Even if you have a penny to your name you’ll find a pocket of joy.

We’re programmed to stop being joyful when we get to a certain age, and you forget about those values. We’re told that as adults we can’t do those things anymore.

With anything you do there always will be critics. People often question why we should enjoy fashion or why design should be fun and playful. They argue that design should be serious.

However, as creatives, we should consider how objects can create moments of joy. That idea should run through fashion, architecture, and even film. I think initially people think they don’t need joy. It’s only after they engage with it that they feel the effects and rethink it.

Dreams are how I built my studio. My world is driven by a desire to keep dreaming and questioning things. It’s about pushing the space and asking: Who owns space? How do we own space? How do we share space?

The Nigerian parable that says “No matter how long the neck of the giraffe is, it still can’t see the future” is about not judging someone by appearances—it’s about equality and respect.

Having the longest neck doesn’t mean you’re better than me. There’s a level of humor in my work achieved using parables. I want to make you feel comfortable but also uncomfortable. I want to ease you into my world. I want to tell you things you might not be aware of.

My parents used parables to teach us life lessons. Instead of getting a smack we would get a parable. I would be in tears because a parable cut so deep.

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 12. Subscribe today