The award-winning architect is known for projects like his stacked rock house in Chile, a music hall that opens into a Hungarian forest, and minimalist homes all over Japan. He has a global following, with one fan describing the effort to find one of his Tokyo structures as a “wild Sou Fujimoto chase.” We meet at Sou’s office—a spacious, waterfront warehouse overlooking Tokyo Bay—to chat about the question that has driven his career: how to balance nature and culture. The question first came to him while at the University of Tokyo, when he thought about how the metropolis was similar to his hometown in rural Hokkaido. “Here in Tokyo nothing is natural, but I still somehow feel like I’m in the middle of the forest.”

Sou initially planned to study physics after a book on Einstein intrigued him with its possibilities for new understandings of space, time, and light. “It was my dream to come up with a new theory,” he says. Admitting he “understood almost nothing” in his coursework, however, he switched to architecture after recalling another book—this one by Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí. That blend of physics and creativity spoke to Sou deeply.

- A love of art and science is clear in Sou’s office, where his unconventional structures come to life via project models on foam boards covered in carpet samples, dried flowers that represent trees, and, on one model, a theater audience invoked by rows of plastic chairs the size of thumbnails. Photo by Irwin Wong

- Photo by Irwin Wong

Have you always been interested in creating things?

Yes. I loved to build cars and other objects using clay or materials like timber and trash, beginning when I was around 3 or 4 years old. My father was a doctor, but he was also interested in art and had many books and paintings. I think this artistic environment also encouraged me to start making things early on.

Is it fair to say you’re someone who likes to go against the grain and do things differently?

I guess so. After university, I chose to step back from the mainstream architectural world and stay alone quietly to think about how to create architecture. I was shy; I wasn’t brave enough to bring my portfolio to big-name architects, even though I loved their work. I got my big break after I took second place in a competition where Toyo Ito was a jury member, and he mentioned my work in a magazine. From that point onward, I was invited to join the existing architectural scene.

- A scale model of Benton Hala Waterfront Center in Belgrade, Serbia, by Sou Fujimoto Architects. Photo by Irwin Wong

Your use of everyday objects (Post-it notes, staples, bath sponges) with vastly scaled-down human figures next to them in models is so simple, yet so imaginative. How did this first occur to you?

Using models to play with objects and scaling is common, but doing it with daily items was a small invention on my part to represent how architects see space in an easy way. I really love using scaled models in exhibitions because they show the fundamental relationships between space, scale, humans, and functions. I did this at the Chicago Architecture Biennial in 2015, where I made 70 models of everyday objects and laid them out as an installation in a huge exhibition space where visitors moved around. The works are now exhibited at MOMA, who later bought them.

What is your process for creating a new work? Do you know where a particular piece will live before you start, or do you first “feel” a space and let that inspiration help you conceptualize the structure?

I sometimes get an idea for a structure and then try to imagine what kind of spatial experience is possible. Other times I try to imagine the type of structure or form that’s suitable for a specific space. In a sense, the process is always quite chaotic. There is no clear or simple way of thinking, just a lot of trial and error.

- Final Wooden House in Kumamoto, Japan, designed by Sou Fujimoto Architects. Photo by Iwan Baan

Your Final Wooden House is stunning. It reminds me of a relaxing sauna. Being in Kumamoto, I imagine it must be somewhat at the mercy of the elements, due to all of the natural disasters there. Is this something you need to consider?

It is indeed an interesting structure … That area is suffering a lot from climate change. The climate issue is something we need to consider more and more. Even within Japan, there are totally different climates. In Hokkaido it’s very snowy and cold, for example, while in Kyushu it’s really hot and rainy. Climate is a priority consideration for every project, but in a sense, everything is a priority: lifestyle, site conditions, cost, budget, regulations. In the end, you have to integrate all of these elements into one form and space without sacrificing anything.

L’Arbre Blanc in Montpellier is breathtaking. I want to live there! How was the experience?

I agree; it’s a really fantastic space, and the client loved it. The project was quite challenging, though, since it represented a totally new concept of living in the sky. The basic inspiration came from the local Mediterranean climate, where people spend most of their time on outdoor terraces. It’s a multiple-level structure with 17 floors and a rooftop bar overlooking the city, which is a great place to watch the sunset. Instead of putting something like a luxury penthouse on top, we proposed a bar that’s open to the public. This initially posed a challenge for the developers, but they ended up agreeing, and now it’s a really popular place among local residents.

The other design team members were all young French architects who are very open-minded, and they too viewed this as a great opportunity to open an exclusive spot to the public. We opened an office in Paris after winning the competition, and we’re now working together for competitions and projects, both in Paris and beyond. Sometimes collaborations can be terrible, but that has not been the case with this team. I also realized from this experience that the younger generation is quite open. We have tough discussions but always with respect.

- L’arbre Blanc in Montpellier, France, designed by Sou Fujimoto Architects. Photo by Iwan Baan

I love your concept of the “formless form” rather than typically defined structures and spaces. The “bookchair” concept for Alias blew my mind. Where do you get your inspiration?

When I create something I tend to use four different methods. The first is my sketchbook, where I do physical sketches in the form of shapes. Next are sketch models, where I use easy materials to make something in a roughly improvisational way. Third is my laptop, where I start with a few connecting keywords or sentences as a hypothesis. This can be effective for pushing an idea forward, since it does not a have a shape or form. And finally, I engage in conversation with my team members and clients. Each of these four methods uses a different way of thinking, so if I get stuck on one of them, I can just move on to another to get inspiration.

Can you describe your daily routine, if you have one?

I go to Paris once or twice a month to work in my office there and stay for a week or so. I also go to China once a month to work on projects. So traveling is definitely the norm for me. No matter where I am, I check emails from my team members every day so I can give them feedback using my iPad. This is a great tool for hand sketches, which are quite important for my work.

And since I now have a small son, I try to spend more time now with my family. I love to play with my son using Legos or building mazes. I used to come back to the office after dinner and work until midnight, but now I leave around 6pm and stay at home, checking emails if I need to. This is not so common in Japanese architectural offices (compared to the more common notion of staying late). I am thinking about the quality of my projects and also of my family life.

- Musashino Art University Museum & Library, designed by Sou Fujimoto Architects. Photo by Daici Ano

Would you say you’re something of a digital nomad?

Yes, somewhat. Even when I’m in Tokyo, I often go to the Starbucks near my home and communicate from there with my teams in both offices. I’m able to do this because I have really good project managers, and my teams always stay connected. I prefer emailing with them instead of Skyping, since I find writing to be so much more clear, obvious, and quick.

What is your decision-making style?

My staff members make preparations for projects, but I sign off on all of the final decisions. This is basically a matter of ensuring consistency, as one wrong choice can destroy the harmony of a structure.

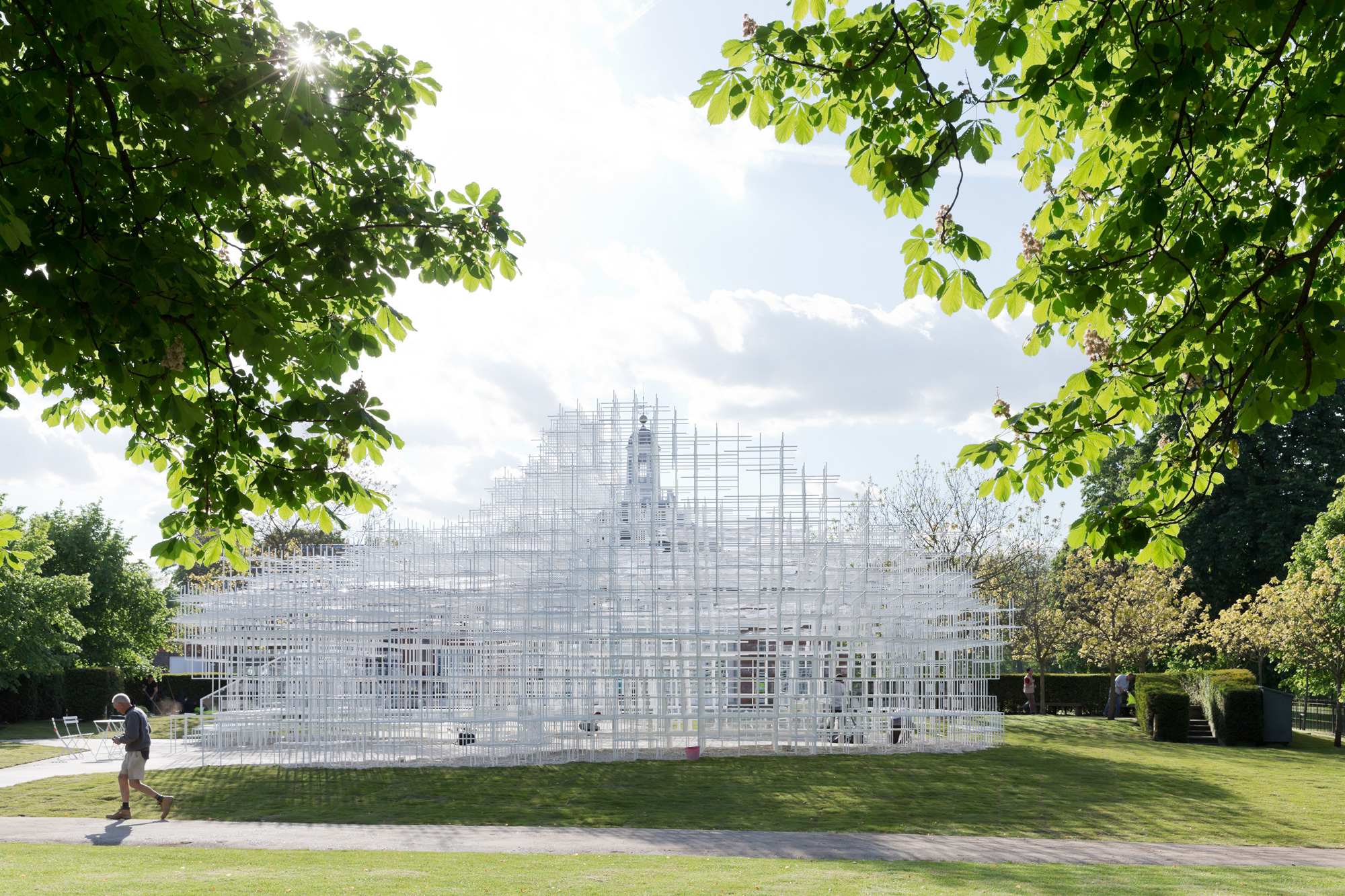

- Sou Fujimoto’s Serpentine Gallery Pavilion in London in 2013. Photo by Iwan Baan

You’ve said the grid shape of the cloud-like structure for the Serpentine Gallery pavilion represents the architectural order, but that this transforms into something organic when many grids are placed together. Could you explain?

The topic of order and disorder is an exciting and very important one in architecture. Architectural design is always thinking about how to make order out of chaos, and at the same time, our behaviors are always organic and unpredictable. I love to find a balance between order and what lies beyond it. The natural order is really complex, but it does have an order. Grids represent a strong sense of order in this pavilion, but placing many of these organic shapes together makes it seem more understandable.

Are you particularly interested in ideas like these because of your background in physics?

Yes—how to create order, harmony, and balance is a fundamental question arising from physics. Our lives should not be limited by order; we need it, but we also need to be free from it. This type of balance or coexistence can be realized if a structure is designed properly.

I first learned that nature has its own order while playing outside in the forests of my hometown as a child. This order is not so obvious to humans, but it can inspire us to behave in ways that go beyond ourselves. Both the natural and the human-made order always inspire me, and I love to find new ways to integrate both of them into my work.

Many of your structures invite us to contemplate other ways of living. You’ve also said architecture can help create new frameworks for our understanding of the world, which is particularly inspiring given the planetary emergency we’re now facing. Where does your inspiration come from?

For every project, I love to think about something new for the future that can bring us a better life. And at the same time, I always love to think about the fundamental aspects of the human species: our bodies, size, behaviors, limitation of movements, perception, et cetera, although, of course, this can vary by culture.

I feel that the field of architecture together with new technology can offer us a future by first returning to a starting point or something fundamental. I think a really important question is how to contrast or integrate basic, primitive elements of human life together with the future—even though we don’t yet know what that future may hold.

- Sou redefined the rental house concept for the 2016 Tokyo House Vision exhibition with Rental Space Tower. Photo by Sou Fujimoto Architects

- Another view of Rental Space Tower. Photo by Nacása & Partners Inc.

What are you working on now?

I’ve got a nice variety of projects going on. In China I’m involved with many competitions and ongoing projects, including a structure that’s a mixture of guest rooms and an event hall in a village. It’s part of a hotel, but it’s really difficult to describe. I also got a commission to design a large tower in the south of China and a small commercial building in Shenzhen.

In France I’m working on different projects, including a university building, spa, hotel, housing, and mixed-purpose structure. Most large projects in France are for competitions—they have a really good system for this purpose. You submit your CV, and then they choose three to five teams. We are also doing an urban master plan in the south of France.

Elsewhere I’ve got a project in Switzerland with a university, and another in Brooklyn, which is confidential but is part of an initiative related to co-living.

Here in Japan, I’m working on two hotels—one in Tokyo and another in Maebashi, Gunma—as well as two private homes and a university project. We are also now working on our third public toilet for a local railway company. And I won a competition for a local artistic space in Towada, Aomori prefecture, which includes a small gallery and community kitchen. These types of small, human-scaled community spaces are getting more and more popular in Japan—and the unique context in Towada is a link between contemporary art and local peoples’ lives. I am also designing a town hall with small community and event spaces in Higashikagura, Hokkaido, which is my hometown, so it feels really special.

And I’m working on a cultural complex and community space in Ishinomaki, Miyagi prefecture with a theater and museum, which were demolished in the 2011 tsunami. I’m hoping this will be completed in two years, before the next biannual festival they have organized to help rebuild their communities.

They are still having a hard time in the disaster region even more than eight years on, aren’t they?

Yes, they are. People are doing their best to stay positive, but it’s tough there. I aimed to make something with a really cozy atmosphere, including a café, library, art gallery, local culture museum, kids’ space, music center, and tatami room for the tea ceremony and other gatherings. It’s a structure that really puts the local people front and center.

You’ve definitely got a lot going on, and it all sounds exciting. What’s your team like?

I’ve got around 50 people in Tokyo and 30 in Paris. Both offices are really international: There are around 10 different nationalities in the French office and 12 or so in the Tokyo office, including many Asians.

- Sou’s Bookchair Collection for Alias draws inspiration from the relationship between architectural space and the human body. Photo by Alias

- The office of Sou Fujimoto. Photo by Irwin Wong

Who or what inspires you?

Architecture-wise, I’m a great fan of Frank Gehry and Jean Nouvel. And I love contemporary and historical art. I find history in general to be really inspirational. I also love walking through all types of cities, both old and new, to see the local structures in their urban context and to see how people live. I get really inspired by things like cathedrals.

What do you love most about Tokyo?

Tokyo was the starting point for my architectural thinking because of the contrast with my hometown. I am fascinated by the small pathways and back streets here, where everything is small and fits to a human-sized scale. It feels like everything surrounds you in a really organic way. I feel nature and artifacts in this city really show their similarities and differences and are constantly mirroring and reflecting each other.

This article originally appeared in the Fall/Winter 2019 issue of Sixtysix with the headline “Sou Fujimoto.” Subscribe today.