I walked over a 4-foot snowbank and threw a leg into a 2020 Lincoln Aviator Reserve. The press wranglers had just dropped it off, and I had a week to kill and another chunk of Chicago winter to escape. I decided to head to Sarasota, Florida—one of the warmest cities in the country and home to some amazing Sarasota modern architecture.

The Lincoln Aviator Reserve came in silver radiance metallic with sandstone leather interiors. Underneath the hood was a 10-speed twin-turbocharged 3.0L V6 operated by piano key shifters. Inside was the 14-speaker Revel audio system and Lincoln’s Co-Pilot360 package. It all sat on 22” alloy wheels—but more on that later.

I popped the third row down and threw in four suitcases, my partner Laura, my dog Koda, 80 pounds of dog food, and the car still had room to spare. The roads were slick and icy, so I twisted the knob to the “rainy” drive mode and set off for the 2,500-mile trip.

The Aviator is an easy driver and handles noticeably better than its bigger sibling the Navigator, although with a quick curb-side glance they appear similar in scale. The 2020 Aviator is all-new, built off the Ford Explorer architecture and upgraded with luxury finishes like wood finishes, 4-zone climate control, and a 360-degree camera.

I got settled in for the ride, including the most boring part—the large stretch of Indiana that seems to never end. At 6’ 1” I found the driver’s chair a bit snug, which is a weird experience for such a large vehicle. Besides that, the ride was everything you would expect from a luxury SUV—well considered and easy to drive and park.

- The Lincoln Aviator Reserve. Photo by Chris Force

A Driving Tour of the Sarasota School of Architecture

The city of Sarasota is a great location for a DIY driving architecture tour (AIA has a free handy booklet and map available for download).

Sarasota Modern grew out of the post-war (1941-1966) housing boom, led by architects Ralph Twitchell and Paul Rudolph. Their buildings—with open floor plans, savvy use of daylighting, and natural ventilation—captured international attention. The time was critically considered the most interesting period of architecture happening on the globe.

When mid-century modern homes fell out of style, many of these buildings were demolished. In 2003 a restoration effort began, led by the Sarasota Architectural Foundation.

There are more than 70 architecturally significant buildings recommended on AIA’s list that are visible from the public right of way—I was able to view about a quarter of them. Here are three of my favorites.

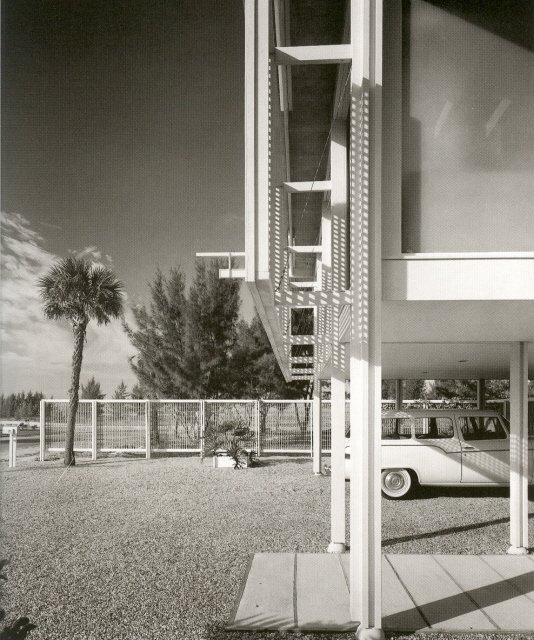

- The Martin Harkavy House designed by Paul Rudolph. Photo by Chris Force

Martin Harkavy House, Paul Rudolph

If you can only visit one neighborhood during your tour a safe bet is Lido Shores, where 11 of the buildings are located, including the Martin Harkavy House (113 Morningside Drive), designed in 1957 by Paul Rudolph with an addition in 2006 by architect John Quinn.

Paul went to school at Harvard, where he studied with Walter Gropius. Walter, who was born in 1883, was a founder of the Bauhaus school along with a few names you’ve probably heard of, like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

In 1941 Paul moved to Sarasota where, while not attending Harvard, he worked until 1958. He then moved to Connecticut to chair the Yale Department of Architecture, where he trained many notable architects, including Norman Foster. He also designed the building he would end up working in.

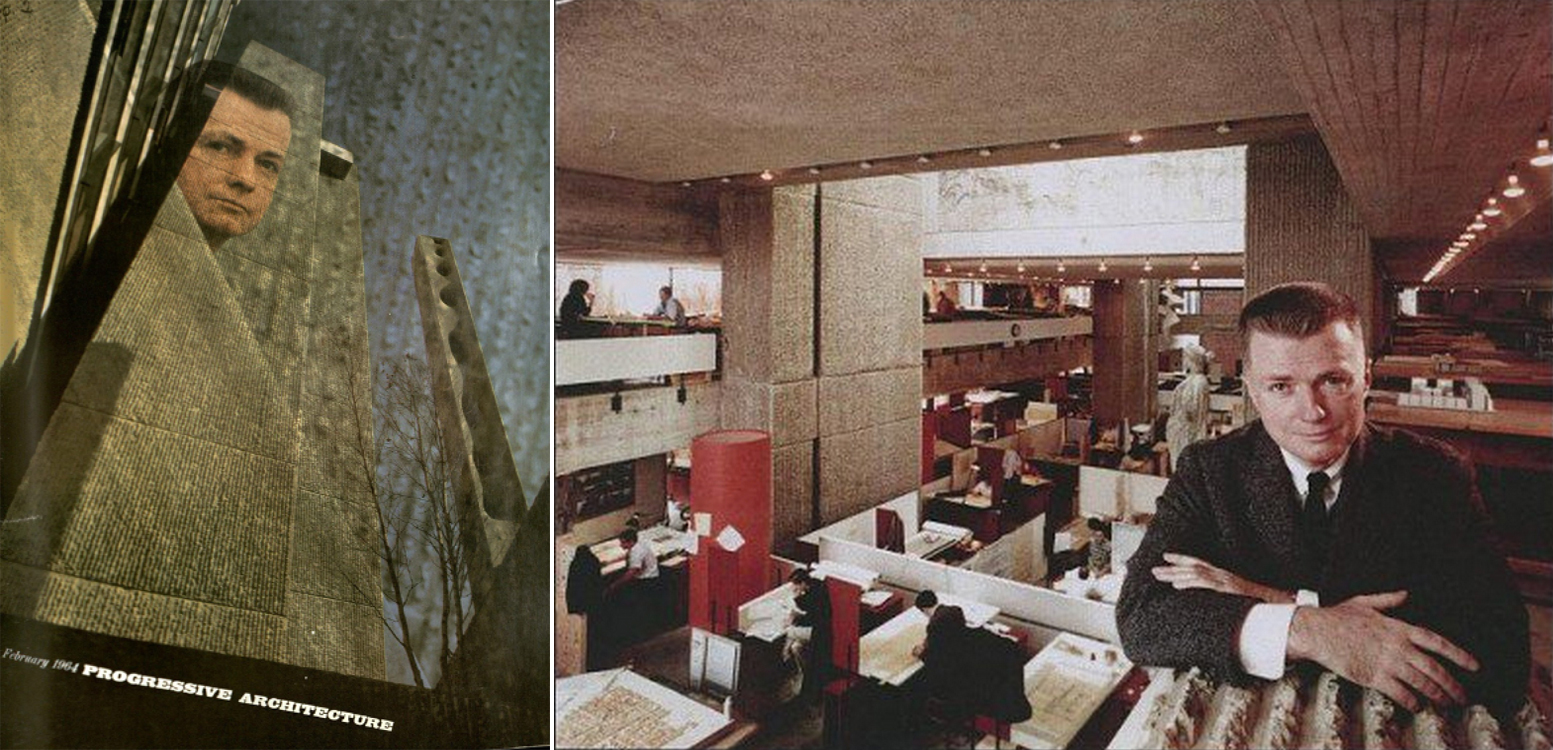

Paul was considered by many as withdrawn and unapproachable with a matching hyper-masculine aesthetic in both his buildings and his haircut. To illustrate his look, 1964 Progressive Architecture magazine blended a photo of Paul, with his tight military haircut, on top of the building he designed for Yale. (I think this was the last documented time anything American architecture–related showed any sort of humor.)

Progressive Architecture, 1964. Right: Paul Rudolph in the Art and Architecture Building, 1964. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Carl Abbott, one of Paul’s students, had this to say about him as a teacher:

“He was very violent to some students and amazingly generous to others. If you were in a group he really cared about, he would push you harder than you could ever stand, and he would make you see things in your own work that you could never have possibly seen.”

Paul, who was gay, lived with his partner Ernst Wagner in New York City until he passed in 1997 from cancer.

- Photos by Ezra Stoller, 1957

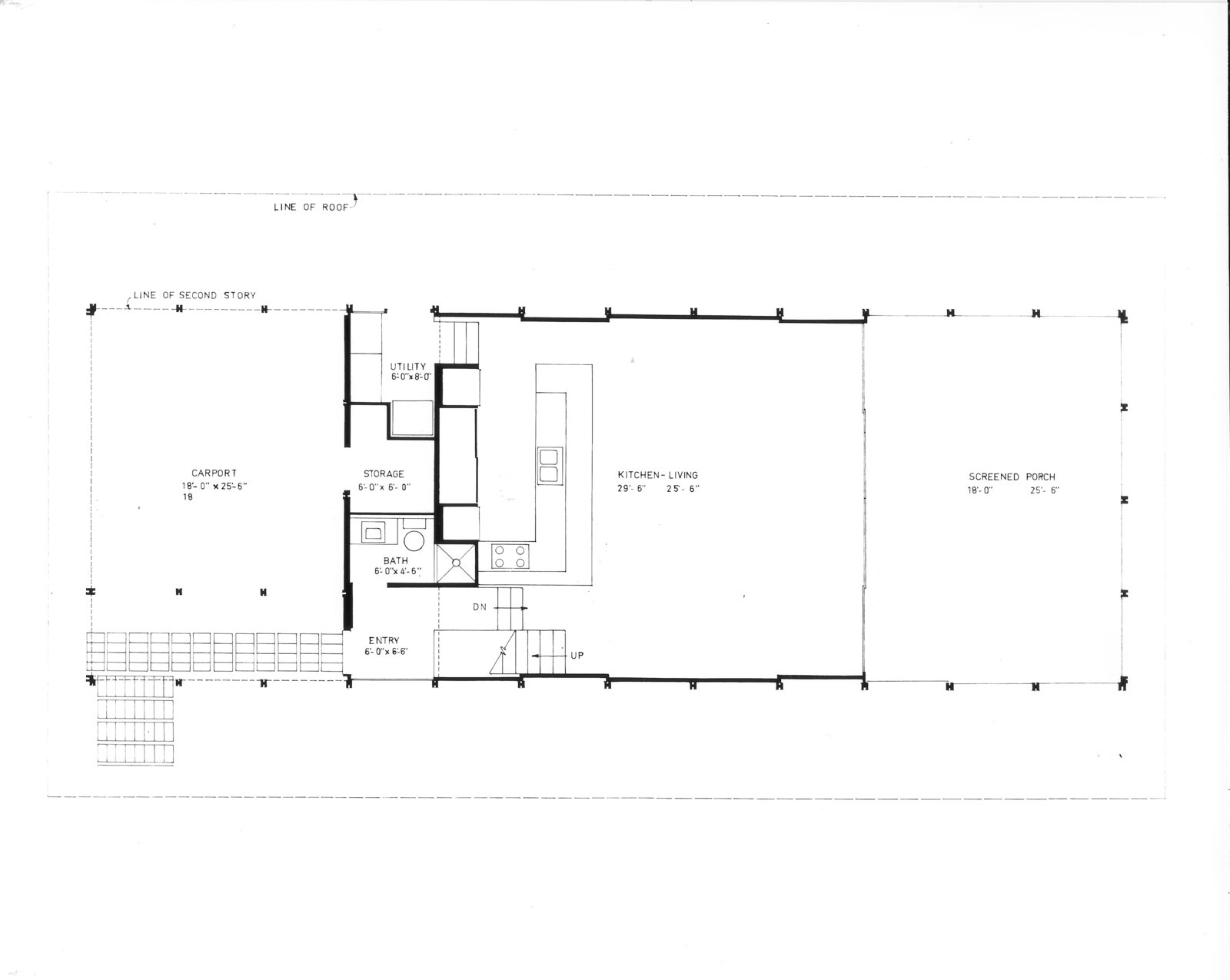

The Harkavy House was built on a three-part grid—the bedrooms, the living room, and the outdoor space—all separated by sliding floor-to-ceiling doors and designed to maximize natural light. The layout is considered an “inversion of traditional Southern porch culture” that emphasized a more private life in the back of the house.

Drawing courtesy of the Library of Congress

Susan Harkavy grew up in the house. She told architect Joe King this about living in it:

“We moved there when I was 1 year old, and I lived there until I was 18, so I never knew anything different until I went to New England for college. It was only after I moved that I had the perspective to understand how unique the house was.

The first thing I understood about the house was the light. The white terrazzo floors, white ceiling, white dining table, the sliding glass doors to the porch, the sliding glass windows upstairs, the ability to laterally slide open the east and west two-story walls, all helped to create extraordinary light.

Paul Rudolph’s rigorous design had such a profound impact on me growing up that I became a sworn modernist and focused on it in my professional PR practice.

You may not realize it, but there was a ton of storage. Rudolph thought of everything. The built-in cabinetry in the living room and kitchen, and above the kitchen (under the Shoji screens) offered clever and efficient storage.

I’d also like to mention the tie-in with nature. The driveway was covered in small stones, and had beautiful trees in square planters. There was a Japanese garden under the stairs with a fountain. There was a beautiful rectangle of green grass where the pool is now. And you could open up the walls to the gardens on both sides. Even if the walls were closed, you could see the back garden past the porch. This was all a very carefully planned way to soften the rigidity of the geometry.”

Hiss Residence (Umbrella House), Paul Rudolph

- Architect Paul Rudolph, cofounder of the Sarasota Modern movement, with a rendering of his Umbrella House. Photo courtesy of Sarasota Architectural Foundation

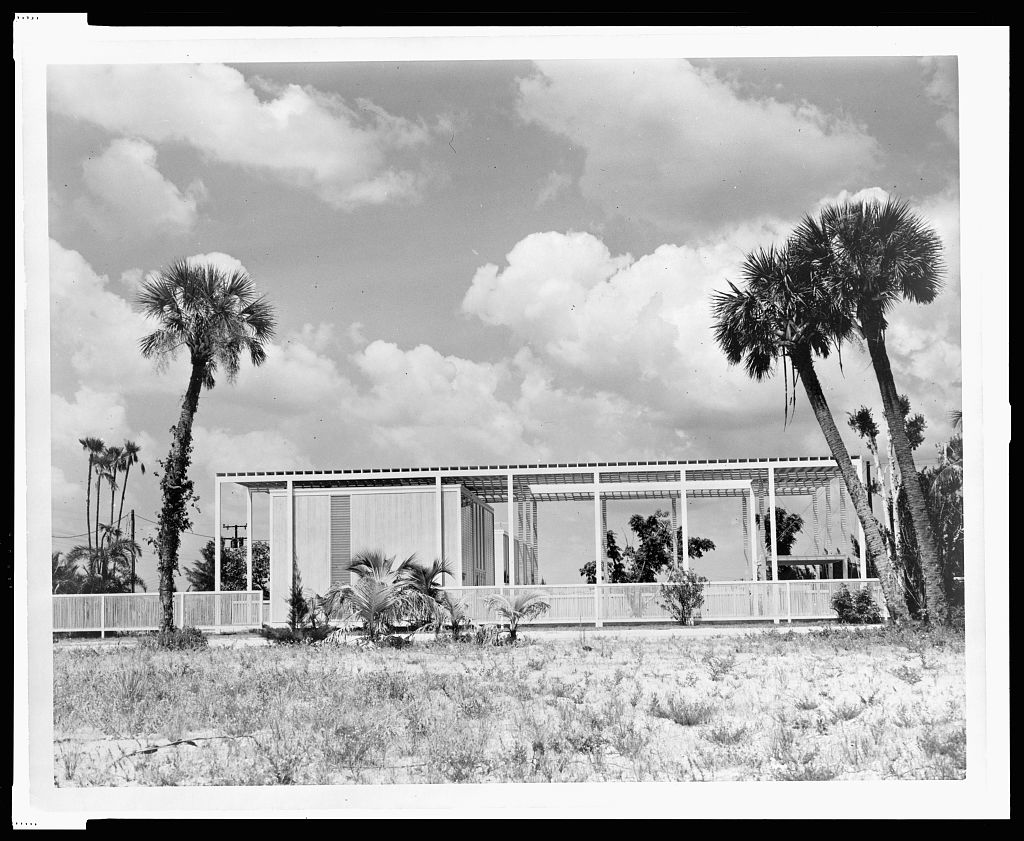

- Umbrella House (Library of Congress). The concrete balls at the base of the columns were made by pouring concrete into beach balls.

“The Umbrella House was built in 1953. Air conditioning existed, yet Rudolph shaded the house with an umbrella canopy, buying tomato sticks from local farmers to construct the slats. It is so ahead of its time—not just in its beauty, but in the way it coexists with nature,” says Lawrence Scarpa, principal at Brooks + Scarpa.

The Umbrella House (1300 Westway Drive) was commissioned as a show home by Philip Hiss, who developed Lido Shores. (Completely unrelated, but Philip also toured South America solo in the 1930s on a Harley-Davidson and sailed around the globe. He was the cousin of Alger Hiss, who worked for the US State Department, helped created the United Nations, but was also a Soviet spy!)

Umbrella House by Paul Rudolph. Photo by Chris Force

The house was intentionally built on a curve to be easily seen by pedestrians and press driving by and was widely recognized as a ground-breaking work of residential architecture with huge advancements in passive solar design.

Over the years the house was not well maintained. In 2005 it was put up for sale at auction with no takers but was later purchased and renovated. In 2019 the house was listed on the US National Register of Historic Places.

- Bee Ridge Presbyterian Church designed by Victor A. Lundy. Photo by Chris Force

Bee Ridge Presbyterian Church, Victor A. Lundy

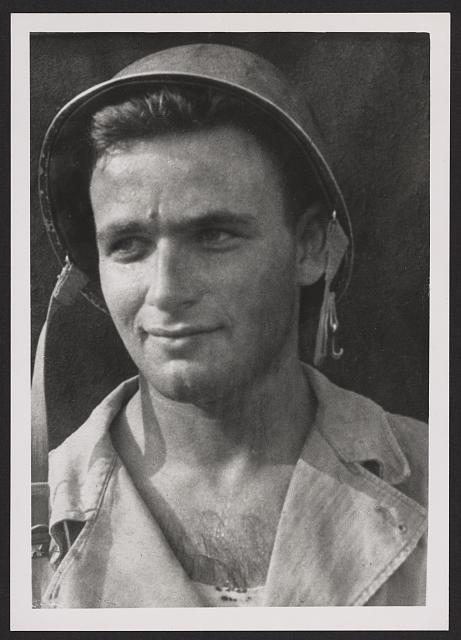

Victor Lundy was a key architect of the Sarasota Modern movement. Victor, who is currently 98 years old, drew and painted as part of his practice. He served in the US 26th Infantry Division in WWII and celebrated the end of the war in Times Square. “I carried a bottle of Listerine and kissed every female I could find,” he says.

- Victor A. Lundy wearing military helmet in 1944. Photo courtesy of Victor A. Lundy Archive, Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

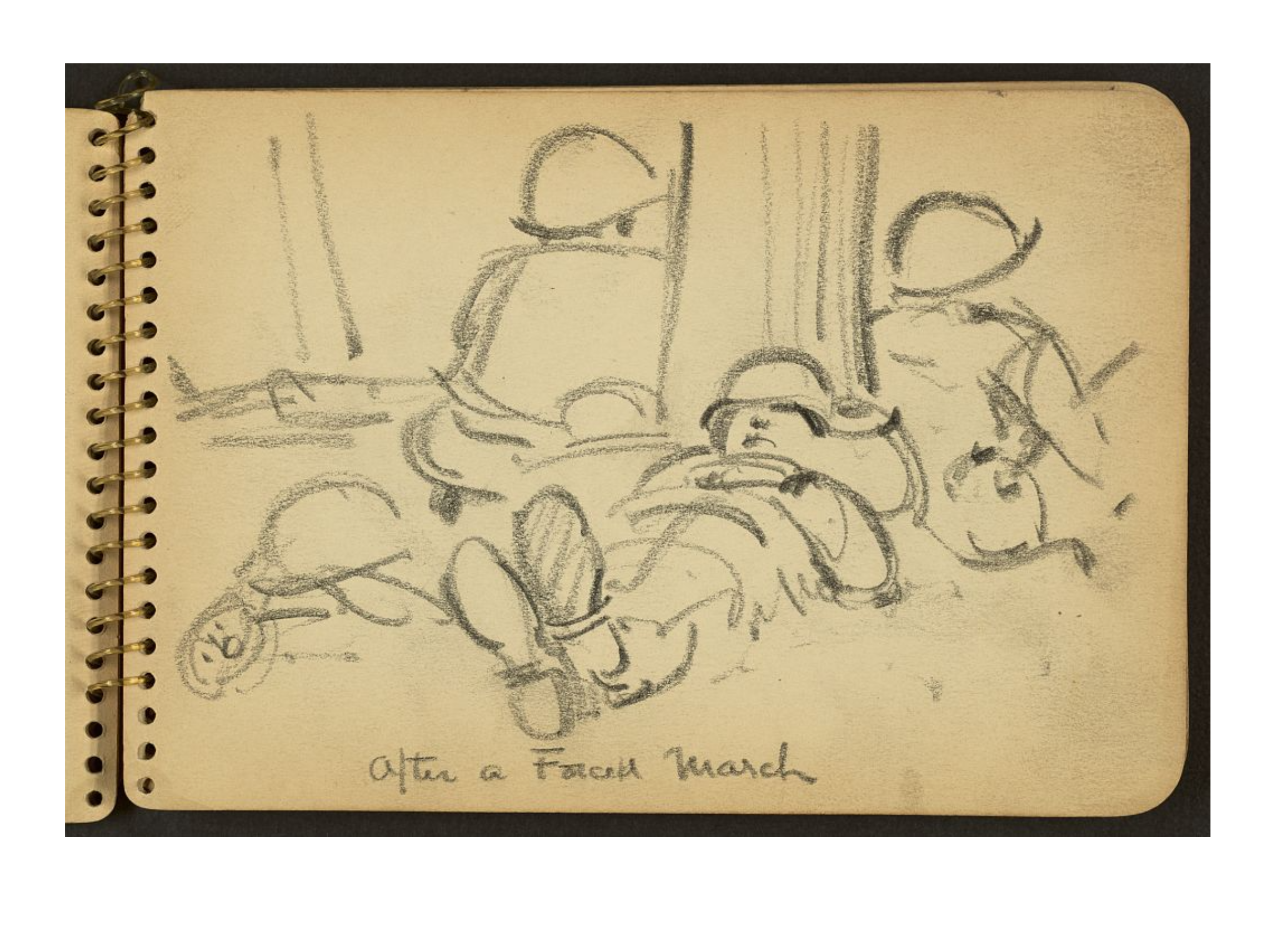

- Sketch by Victor A. Lundy

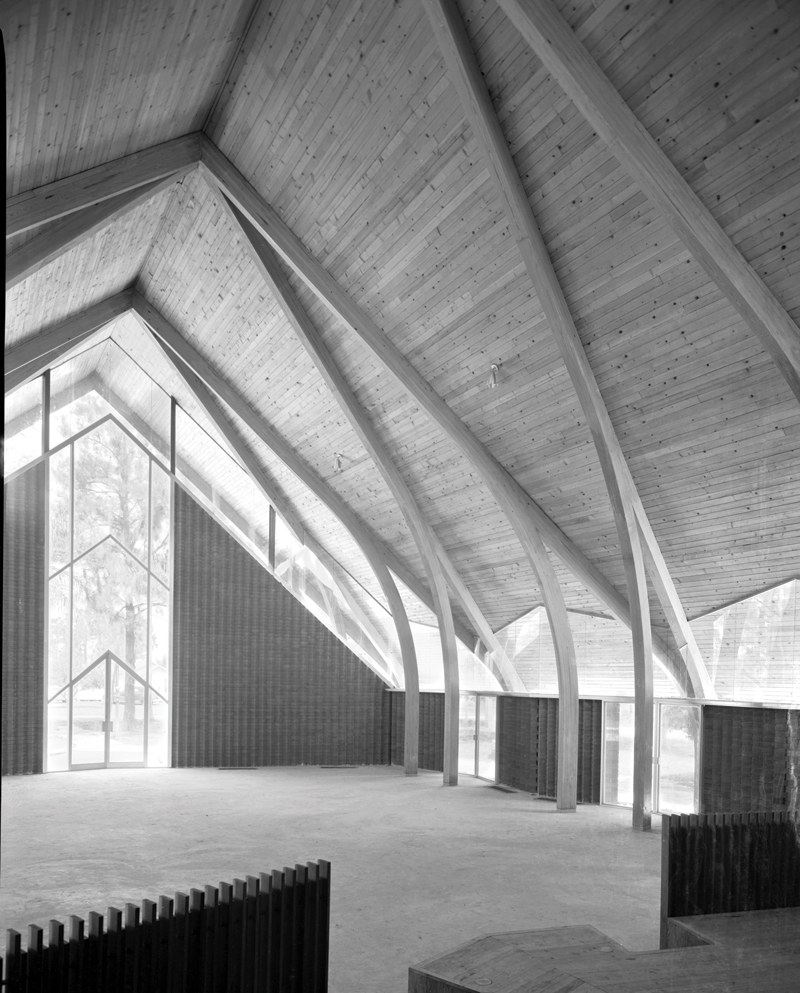

Lundy is a lesser-known architect, possibly due to the fact that his styles were so varied. His beautiful drawings brought a sculptural effect to his buildings, especially to the dramatic rooflines of the churches he created like this one for the Bee Ridge Presbyterian Church (4826 McIntosh Rd).

Bee Ridge Presbyterian Church, 1956. Photo by Alexandre Georges courtesy Princeton Architectural Press

Lincoln Aviator Reserve

With my eye for design details tuned up, I headed to the beach for a final photo opp with the Lincoln Aviator Reserve. The fit and finish of the Aviator is well done, the silver radiance paint job shines, and the four sweeping lines of the hood add the “aviation” vibe to its design language.

- Photos by Chris Force

Touch-sensitive LED interior lights, light-touch door handles, and soft close doors add a luxury feeling. When entering and exiting the suspension also lowers and raises itself. I found the power fold rear seats handy but lacking on the middle seats.

While driving, the buttons on the steering wheel map themselves to whatever function you’re using—it actually makes a lot of sense and is intuitive while using them. I find heads up displays annoying, so I turned it off. The 110 outlet turned out to be really handy to charge up laptops while on the road.

Overall the Aviator offers every bit the lavishness you would expect from Lincoln and is a perfect companion for any pandemic-related driving-only architecture tour you’re considering.