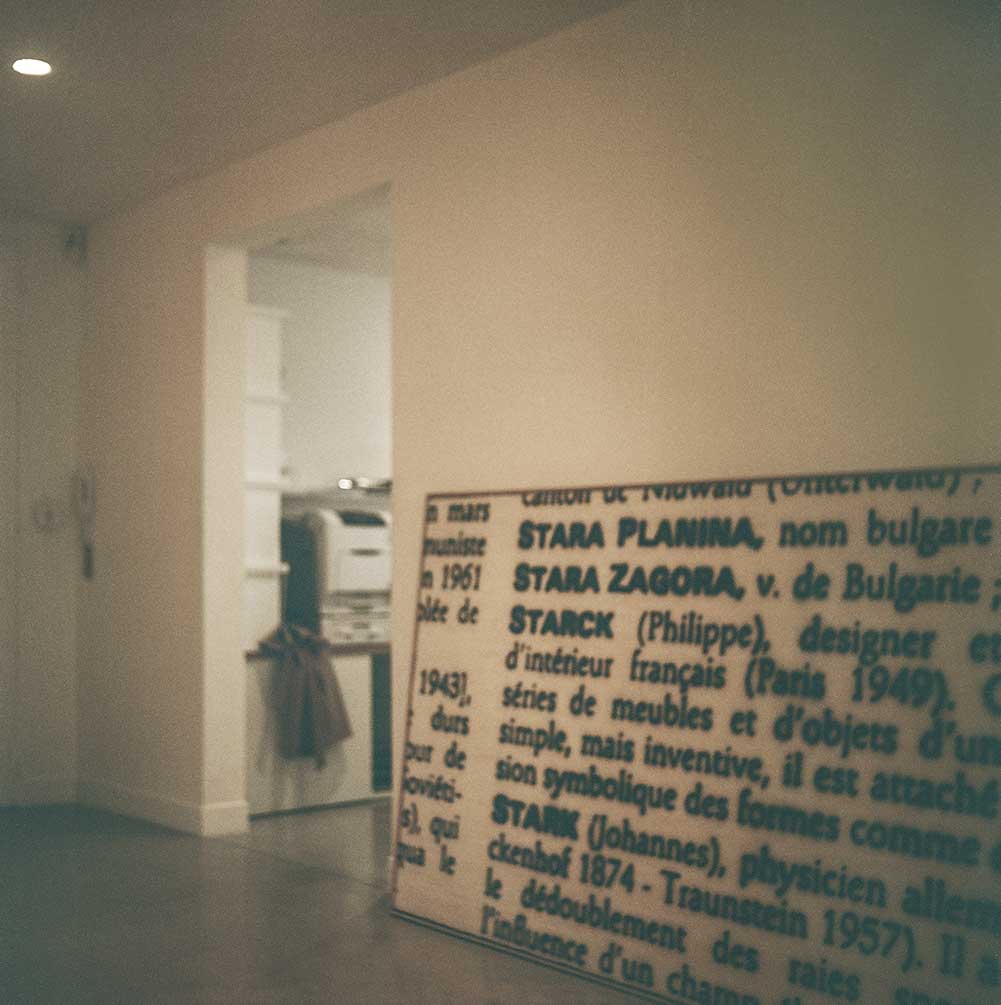

If you went to high school in France in the early 2000s, you had to take a course called Technologie, our version of Home Ec where we learned to use a soldering iron, make a bike light, or—and I’m quoting the curriculum—appreciate “the evolution of objects through time.” I remember one sheet the teacher projected on the wall that was meant to explain the concept of design. I can still see one image clearly—Philippe Starck’s wine bottle opener. I think we also studied his orange juicer that day. French students truly study Philippe in school—he’s in our encyclopedia. “French designer and interior architect. Creator of furniture and objects of simple yet inventive structure, he is sensible to the symbolic expression of both shapes and space.” The definition hangs in the entrance of his Paris offices. As I read the words and prepare to meet the man who’s lent his genius to countless projects—from iconic chairs to Tokyo architecture to a yacht for Steve Jobs—I hear a cheerful voice; he’s here for the interview. We sit with his wife, Jasmine, around a large table. The couple is just passing through Paris, and the team is trying to get as much time as possible with the boss. Everyone is busy in the office overlooking the Place du Trocadéro, but it won’t be long before the Starcks head back to Portugal. There, Philippe lives in a large house with his office on one side and his wife’s on the other. When he’s home, he says Jasmine is his only connection to the outside world. We talked to Philippe about what it means to him to create.

- Philippe Starck is literally in French dictionaries. Photo by Élodie Daguin.

- Whatever medium he’s working in, he approaches it from the same perspective. Photo by Élodie Daguin.

Do you remember the first time you realized an object was designed?

I’ve never asked myself that, since I have never seen the difference between an object designed by mankind, nature, function, material, age, or any of the parameters in which one shape differs from the next. For me, a shape is a shape. Therefore I don’t recall the first time I realized an object was designed. I remember seeing beautiful pieces of wood that had been polished by the river. If we think about it, what’s the difference? By definition, an object designed by mankind would have to be imperfect since again, by definition, that object would be forced into a function, a price, which can only corrupt it.

- Philippe’s Paris office looks out over the Place du Trocadéro. Photo by Élodie Daguin.

- Packaging designs from the Peau de Lumière Magique fragrance campaign, on which Philippe collaborated with perfumer Daphné Bugey. Photo by Élodie Daguin.

How did you realize the importance of an object’s use as opposed to its aspect?

Despite appearances, I am a functionalist. I suspect the word functionalist may have been first pronounced in the 1920s. Then, a certain number of functions were mainly utilitarian. We talk of functionalism when industrialization was underway, when the multiplication of objects was underway. I don’t believe functionalism as a concept existed before then. Since the 1920s, a lot of people changed the way we might see the world. Freud gave a sense to objects, a gender to objects. [French psychoanalyst] Lacan as well. As a result, the parameters have widened considerably.

I have no desire to create an object just to create an object. I see no poetry in the act of creating an object. I am not an artist. Even a great artist can be considered functional since he is bringing something to the people appreciating his art. I am not an artist. I am strictly within the immediate utility. And one of the functions is undeniably the meaning, the influence of the object, which comes from the political, the sexual, the economical, or the sentimental.

- Philippe is a prolific designer of furniture and lighting. This lamp is from a collection for Flos. Photo Courtesy of Starck Network.

- Philippe collaborated with Kartell and Autodesk to design what’s been called the first design object conceived by A.I. Software generated the chair design based on input put forth by Philippe and Kartell. Photo Courtesy of Starck Network.

The function of your objects defines their design. Is there a decision that isn’t dictated by function? Like color?

I see your point, but that never happens to me. I have a logic I apply to every single subject I work on. I have a process, an ethic. I follow a set of unsaid rules. And I don’t depend on a culture. To be more precise, I am not interested in what is cultural. Aesthetics are part of culture. I fear what is cultural because it creates aesthetics that are volatile. And what is volatile is the opposite of the definite. And today, the emergency of longevity is an absolute emergency since it’s one of the true solutions of all environmental issues. I don’t have taste. If I’m asked if pink and green go well together, I simply cannot answer in terms of taste. However, I can answer in terms of meaning. I can tell you that this pink means something and that green means something else and that putting them together would mean yet something else. I express myself through materiality, through shapes and colors. I write novels, stories, articles, simply through materiality. I try to be precise in my language, and succeed in doing so. Even if I lost some words in French by speaking foreign languages poorly, I am still someone who has a rather large vocabulary and who uses it. It’s exactly the same when it comes to my work. I have a good vocabulary, and I know how to use it. I don’t know if the melody is pretty, but I’m certain there are no false notes. The result is I make no aesthetically oriented choices. I say this all the time; it will have only the elegance of the intelligence behind it. For habitat for instance, I say the house will be what it is. It will only be as beautiful as the happiness of the people living in it. I have no judgment, to the point that I don’t even look at the exterior aspect of something I build. I utterly don’t care.

Bentley collaborated with Philippe to create a smart recharging unit concept for Bentayga Hybrid customers—the Bentley x Starck Power Dock. Photo Courtesy of Starck Network.

Philippe is no stranger to designing yachts, but his most famous was easily Steve Jobs’ mega yacht—a project he says even the late tech genius may have gotten carried away with. Photo Courtesy of Starck Network.

In terms of architecture then, what level of detail are you trying to reach?

It is said that God is in the details. I don’t believe in God, but the idea is still true. I could answer differently. Everything is proportions. There is no right or wrong, there are only bad proportions, bad measuring, bad distances. Take a house, for instance. There is a 100-meter scale of judgment, there is a 20- meter scale of judgment, there is a five-meter scale of judgment, and so forth … Therefore God is in the details at every scale. One can appreciate a building by Carlo Scarpa, and the closer you get, you can appreciate a five-meter detail, a two-meter detail, one-meter detail, a five-centimeter detail.

RELATED | Designer Marcel Wanders is the Busiest Man Who Never Works

What is a project where you feel details were explored to the fullest?

It depends. For instance, the Mama Shelter hotel, where some rooms are 90€ per night, it means we have to spend absolutely nothing. It means the most beautiful detail we can offer is to paint the walls with blackboard paint and leave chalks around. The other beautiful detail is to buy [inflatable pool rings] at the hardware store and make a chandelier with that and a neon light. It is both a non-detail and a detail. For this project, it was the best detail we could have.

The Mama Shelter hotel in Bordeaux has a surprising overhead detail at the bar. Photo Courtesy of Starck Network.

Another example we could take is Steve Jobs’ mega yacht. The boat was entirely designed in two-and-a-half hours in my bed in Los Angeles. Yet we developed the details for six years with Steve. It was insane. Hysterical even. Even I, the emperor of details, I remember having to tell him, “Steve, this is starting to be a bit ridiculous.” We spent seven months discussing if an angle should have a 0.3-millimeter or a 0.7-millimeter ray. Philosophically I would get it. But it was flirting with the obscene. The boat will be the last one in history built that way, alongside others I’ve done. The craziest in the details was Steve’s—technological details too I mean. We had to file about 20 patents. When you enter Steve’s boat, you can feel the energy coming from the idea behind it. We were looking for absolute perfection, like monks in a way.

Philippe is designing habitation spaces, crew quarters, and more for the world’s first commercial space station, to be built by Axiom Space. Photo Courtesy of Starck Network.

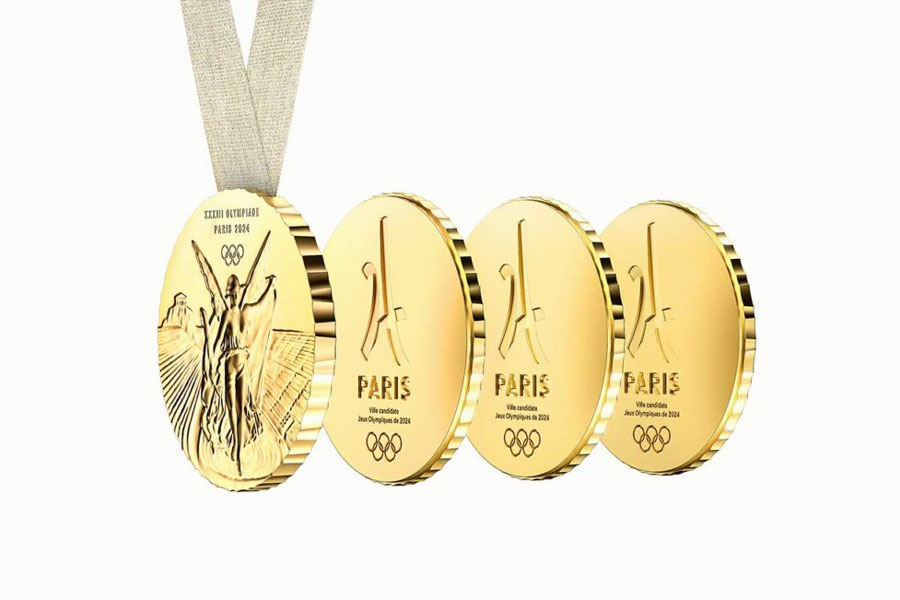

The 2024 Olympic medal designed by Philippe is meant to be shared, as it splits into separate medals. Photo Courtesy of Starck Network.

Do you think about the international space station, a perfume, or the 2024 Olympic medal in the same way? How does the object define how you approach its creation?

There is only one system. The work is always unconscious. The main thing is to find the legitimacy to exist. Why are we going to do this or that project? What will it bring to mankind? What will be its profit? Can it bring back the balance between male chauvinism and what is feminine within design? In the end it comes down to: How can I procure pleasure? How can I procure pleasure to the people who will use the object or inhabit the space? From there, you can know if you have to do the project or not. Sometimes you can still have a weakness for an object you know is not needed. From there, I don’t need to think about it, if I find a reason to do it, everything unfolds. I look for the heart of the project, its soul, and once I’ve found it, I unfold everything. But I don’t even think about it. Not for a second. It hasn’t gone through my head. I only print out what my unconscious has been working on. I do really good drawings, a lot better than computer drawings. Sometimes I even question it myself. I wonder how it’s possible that I work so quickly. And the first solution is always the best.

DIAL is an Individual Alert and Localization Device with a waterproof GPS tag in a comfortable and highly resistant silicone strap. The visible, flexible bracelet connects you immediately with help. Photo Courtesy of Starck Network.

You have often defined your profession as making life better, but you stress that the priority is saving lives. How do you help save lives?

That is the core subject. When I say I am not happy with what I do, it simply is because we have been living for 20 years now in a time of vital emergency. What we try to do is help the best we can with projects like DIAL (a life-saving waterproof wristband that includes a GPS tag within its highly resistant silicone strap) or the Ideas Box for Libraries Without Borders (a mobile multimedia center with educational and cultural resources for people in need, including refugees and underserved communities in developed countries). On those types of projects I don’t charge anything. For DIAL, we didn’t charge [volunteer organization] Les Sauveteurs en Mer, of course. It’s true I’ve been conscious about environmental issues since I was 17 years old. Completely by chance, I met an ecologist from California who taught me everything. I have always done what I could.

- Philippe designed the lavish L’Avenue restaurant, at Saks, in New York. Photo Courtesy Of Starck Network.

- Philippe at work in his Paris office. Photo by Élodie Daguin.

What is your vision for the future? Is there an object you look forward to designing?

Everything around us will disappear. Design was only a cosmetic device meant to make obligations bearable. Yet these obligations are changing, disappearing. There is no longer the need to make them desirable. If a new object were to come into our lives, it would only be temporary. A lot of objects we believe to be eternal will disappear as well because we will discover they weren’t necessarily good for us. Take the chair, for instance. The chair offers only a very bad position for the back. The chair has a very low life expectancy. Reading glasses, too. I wear glasses, yet they won’t be there anymore in maybe five years, as everyone will be operated on in a less and less intrusive way. The list goes on. There is no desirable object in the future; we can only desire that dematerialization will keep on going the way it’s going. Most of all, we can only desire that what I call bionisme [or the concept that human beings will incorporate technology within themselves in the near future] will be finally affordable, controlled, and accepted. The only solution for humankind to keep on evolving is bionisme. For the past 100 years or so, scientists have been calculating the evolution of human intelligence. We haven’t made any progress in the last two years. It’s the first time in history we’re not making progress anymore, which is an absolute catastrophe. If humans are not capable of intelligence, they don’t exist anymore.

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of Sixtysix with the headline “Philippe Starck on Evolving Design.” Subscribe today.