“It’s complicated,” says Paul Wraith, the chief designer behind Ford Bronco.

This is not the answer I was looking for.

I had asked, in a long, meandering, chat-cast kind of way, essentially this: “So, how did you create the all new Ford Bronco?” Dumb, I know.

“It’s so complicated,” repeats Paul, his steely British tone slicing right through my nonsense. Suffering through my question, using not the entire vehicle, but just the door to illustrate his point, he hurls this at me.

“The door needs to start at a point on the vehicle that is comfortable to get your feet in and out but also has a relationship to the crash behavior of the vehicle because it’s attached to the A post, which is attached to the A pillar. The back of the door is driven by your relationship to side impact, ingress, and egress. So there’s a lot of things going on in the door. It’s got its own points of view about life and how it wants to be. And then you take it off, away from its home, and you put it into the rear of the vehicle where it, up until now, it hadn’t a good place to go to be, you know? What was it doing there?

“So, yeah, it’s complicated.”

I consider changing topics. I wonder what Paul had for lunch today. Does he ever miss the pubs in England? Does he call cookies biscuits?

We press on. I set the footing for my next question.

- Paul Wraith may run a 15-person design team, but he also dedicates time to honing his own skills—from sketching to work in CAD. Photo courtesy of Ford

Complicated Electric Shavers

When Mickey Rourke’s character Marv in Sin City said “modern cars, they all look like electric shavers,” he wasn’t wrong. Customer demand, economics, and advanced engineering have made the modern car, especially the SUV, fiercely homogenous. (The new Chevy Blazer comes to mind.)

How, then, 25 years after shelving the Bronco, was Ford able to produce such a gloriously designed vehicle that managed to both draw on its 55-year-old history yet arrive with its own modern identity?

It turns out design, culture, and a lot of luck were responsible.

The modern Bronco’s story could start in 2004 when a concept version (that Paul was not involved with) was debuted at the North American International Auto Show. The concept drew heavily from the original Bronco designs of the late ’60s. It would go on to be driven by The Rock in the film Rampage but otherwise had little mass-market impact.

I realize while speaking to Paul that his 20 years of working within Ford has made him powerfully aware of just how intricate his industry is. “It’s so complicated,” he repeats. (There we go again.) “I couldn’t attempt to articulate some of the potential complexities.”

- “We’ve been very clear as a brand that we put the human in the middle with everything,” Paul Wraith says. Photo courtesy of Ford

“There were passionate advocates trying to get Bronco off the ground,” Paul says. “The 2004 concept was part of that. I wasn’t there then, but I would hazard a guess that the stars just didn’t align correctly enough, and the focus should have been somewhere else, and that was the end.” The project went to sleep.

Then, 13 years later in 2017, it was decided the Ford Bronco was going to make a comeback. I’m not sure exactly how that decision was made. I asked Paul, but I’m not sure he knows either. But I can make a guess that it was complicated.

“This is a passion business. Not everybody can agree all the time and the system does want to pull in different directions, but you will have to come together.”

Shortly after the announcement, Jim Hackett, previously the CEO at Steelcase and a passionate believer in human-centered design, took over as CEO at Ford. Jim, who had turned to IDEO founder David Kelley for his guidance on “design thinking,” began to shift the way Ford thought about developing new product. Instead of beginning with drawings, Paul’s team began with human-centered research.

“We did a lot of research with real people, getting to know real customers,” Paul explains. “From someone who lives in the city to someone who is driving a heavily converted vehicle and is never happy unless they are hanging off the side of a mountain.

We asked, ‘What are we trying to solve with this vehicle? Why bring it back? What’s the problem?’ We started looking very, very deeply at our customers and really working out what was going on in their lives. How could we make their lives a little bit better, easier, more fulfilling? This approach was quite different than the sort of classic car design school of sit down at a drawing board and knock out an amazing rendering.”

“Think of the customer first” led the entire project.

- Paul Wraith’s team used “non-precious” foam models whenever possible to find the right solution to complicated problems. Photo courtesy of Ford

Can You Fit That in the Scanner?

Moray Callum is a Scottish automobile designer who owns a beautiful black 1976 Bronco with a white top and white grill. Even if you’re not the car type it’s the kind of car you point out. Moray is also the vice president of design at Ford. Naturally, when the new Bronco was greenlit, he was excited.

“Moray is very attached to the Bronco program. He owns two, and he worked on one of the previous Bronco projects that hadn’t made it to market. He had a lot of emotional investment and actual practical investment in the vehicle as well. He had a very clear point of view and he’s a terrific leader. He guides the team very well, but he also lets the team get on with it. It’s our job to do the right thing and we took advantage of that,” says Paul.

What that meant was moving quickly. Paul’s team decided to skip additional drawings and models and instead drove Moray’s ’76 Bronco straight into their studio and figured out how to capture a hyper-detailed 3D scan of the entire vehicle.

“We were trying to find the right tool for the problem. If we felt that that scale clay model wasn’t going to deliver us the right answer, that it wouldn’t be the right medium to explore whatever those problems might be, we didn’t do them. However, the entire Ford system has a natural cadence,” Paul says. “It wants to help. If scale models turned up we just didn’t use them. In the process of doing this we did make ourselves a sort of slightly odd-shaped animal that didn’t quite fit the normal sort of sequence of events that were expected. And that’s good. Being naughty is a good thing. The more naughty we can be the better.”

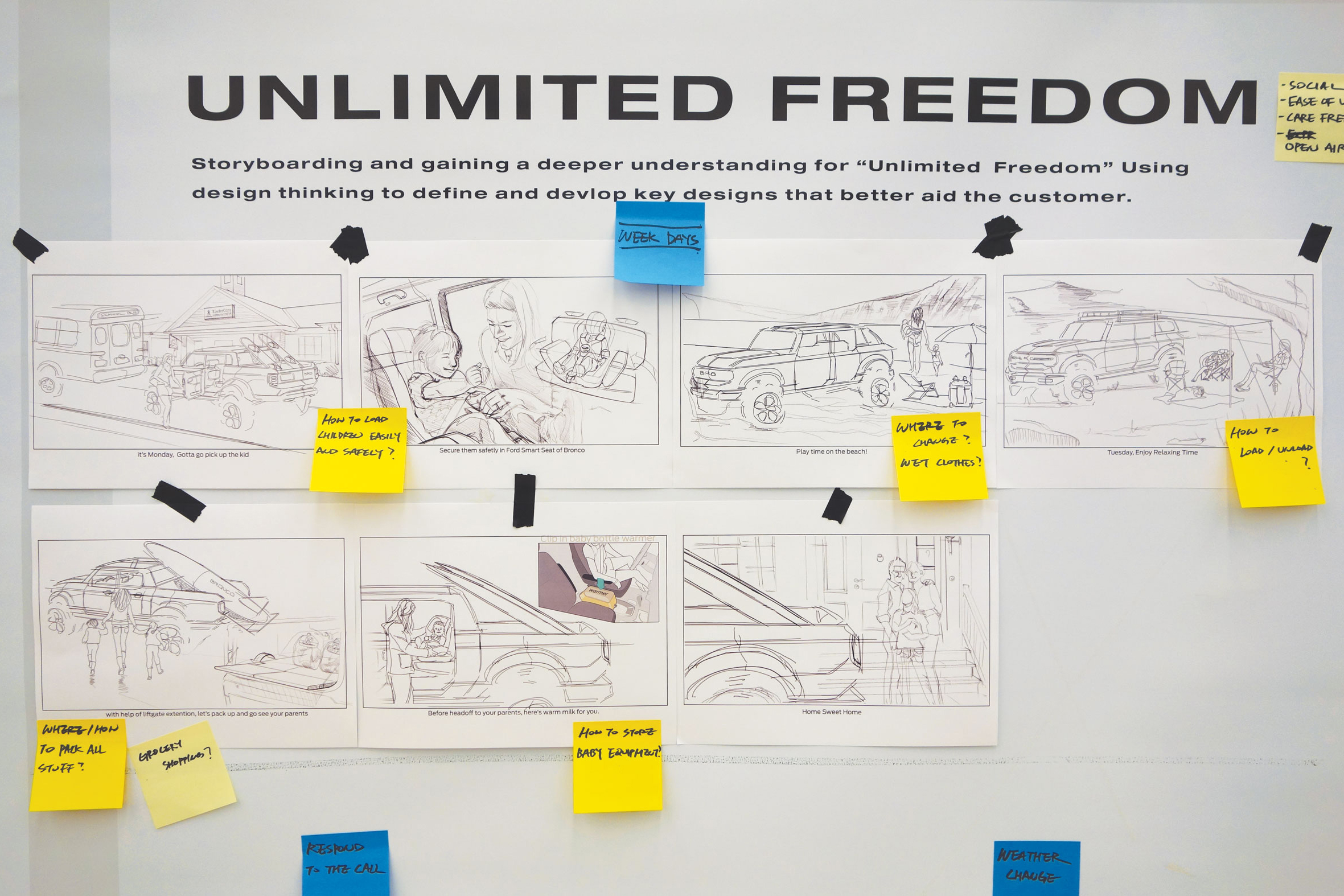

- “We’ve been very clear as a brand that we put the human in the middle with everything,” Paul Wraith says about his human-first storyboarding process. Photo courtesy of Ford

Paul’s immediate team, about 15 designers, works out of the Ford Product Development Center in Dearborn, Michigan, where practically every Ford model since 1955 has been designed. Part of their design process included a weekly customer-focused storytelling exercise. Using not much more than a basic black pen each week the team sketched a specific user scenario.

“We’d challenge ourselves and say, ‘OK, so this week you’re designing for James. Where is he at? Where on Earth is James in this moment? What time of day is it? Is it hot or is it cold? How far has he come? And what’s the ground doing? Is the ground level, or is it an angle? Is it wet and muddy? Dry and dusty?’ That gave us an understanding of what we’re designing for,” Paul says.

Every designer has to balance breaking the rules with breaking their trust with the boss. Typically when car designs are presented for review it’s a massive Hollywood-like experience. Instead Paul was showing Post-it Notes and line drawings. The early review stages were happening, but then it came time to present to the CEO.

“I distinctly recall being told we needed to do it the normal way,” Paul remembers. “I said, ‘This is the new narrative. This is the way we will work for the problems we’re presented with.’ And it turns out leadership was delighted by the methodology we were using and our outcomes. We weren’t constrained and held back. Yeah, we raised a few eyebrows here and there, and that’s all good. If we hadn’t it wouldn’t have been as much fun.”

- “Being naughty is a good thing,” Paul Wraith says of the untraditional design process his team undertook for the Ford Bronco. “The more naughty we can be the better.” Photo courtesy of Ford

Putting People First

“We’ve been very clear as a brand that we put the human in the middle with everything,” says Paul when discussing his design philosophy. But it also carries over to his philosophy as a leader. Paul likes to look after his team and keep an eye on how many hours everyone is working. “There’s enough science out there to demonstrate that if you do 50 hours, 60 hours, you’re wasting your time. You’re wasting everyone else’s time. And in fact, you’re wasting the power bill.”

Instead he likes to focus on setting everyone up to succeed. “You’ve got to give people space to be brilliant. There’s no hard and fast rule about how you manage creative people. We’re all very different characters, but the team is a unit. I’m thankful I know that when they sit down, when they identify a problem and they get that pen out, good things are going to happen.”

- “How could we make [customers’] lives a little bit better, easier, more fulfilling?” Paul Wraith says. “This approach was quite different than the sort of classic car design school of sit down at a drawing board and knock out an amazing rendering.” Photo courtesy of Ford

Every morning Paul is up at 5:50am, though today he might be scrambling to unpack a few more boxes since, perhaps out of pure madness, he decided to move his house the same week he launched Bronco. “Everything either side of me right now is just chaos.”

Despite the towers of cardboard boxes he makes sure to carve out time to draw as often as he can. “I do a little bit less creative work than I used to, but I’m drawing all the time. I keep my skills sharp, so if I need to do a downtown rendering I will do a downtown rendering. I can make stuff in CAD. I still do it. You need to keep your skills sharp. It’s no good trying to ask someone to do something if you don’t know how to do yourself. That’s no good at all.”

As we finalize our discussion of Bronco his thoughts flip from corporate insight to designer renderings to Post-it Notes and safety regulations. They’re all perfectly logical connections to him, the way I imagine a surgeon sees a lump of guts once they’ve cracked open a belly. To me? I see a bloody mess. It’s overwhelming to consider how many parts a car has. How do you not only get it all done, but get everyone to agree on it?

“This is a passion business. Not everybody can agree all the time and the system does want to pull in different directions, but you will have to come together. Some of that creative tension can be really healthy. But nobody was knocked unconscious in a meeting. It was all positive stuff.” But there must have been at least one big argument, right? I push him for a detail.

“It was the horse,” Paul admits.

You mean, the logo? The biggest fight was over the logo?

- The most tense part of designing the Ford Bronco: the horse, says Paul Wraith. Photo courtesy of Ford

“The horse was pretty wild. It was probably the most red-faced, critical, passionate ‘I really am going to stamp my foot if I don’t get my way,’ type of meeting. It was actually about the position of the horse’s front hooves. One of my designers Antony did a beautiful sculpture of the horse, really brought it up to date, and we really liked it. We got very excited with it. So we made one, it was about the size of an actual horse, and it’s attached to the wall in the studio directly opposite from the other end of the studio where there’s a Mustang attached to the wall. Only we made ours about 20% bigger, just because,” Paul smirks.

“But at the point the hoof was quite tipped, like it was balancing on the leading edge of its hoof like a ballet dancer. That was an error, and it made people quite hot under the collar. Like ‘That’s wrong! It’s got to be in the earth, not balancing on a point! This is ridiculous!’ It sounds silly, but actually maybe you need something like that that has a bit of a valve to exercise a bit of steam and energy.”

Paul can’t discuss future projects, but he does say he’s busy on future iterations of Bronco. “I’m scribbling. I’m back to being the naughty boy in the classroom who sat at the back scribbling things.” While Paul gets back to drawing, the rest of the country has lined up to buy his creation: The Ford Bronco already has more than 150,000 pre-orders.

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 05 with the headline “A Complicated Unbroken American Horse Story.” Subscribe today.

Interested in going behind the design of other vehicles? We speak with the designers behind the Toyota Supra, Lotus Eletre, a custom Rolls-Royce Wraith and Livewire.