Nifemi Marcus-Bello is a Nigerian designer known for his context-driven approach to industrial design, often blending traditional African aesthetics with contemporary functionality. His work explores the intersection of culture, technology, and design. Anna Carnick is an

American-born, Berlin-based independent writer, editor, and curator.

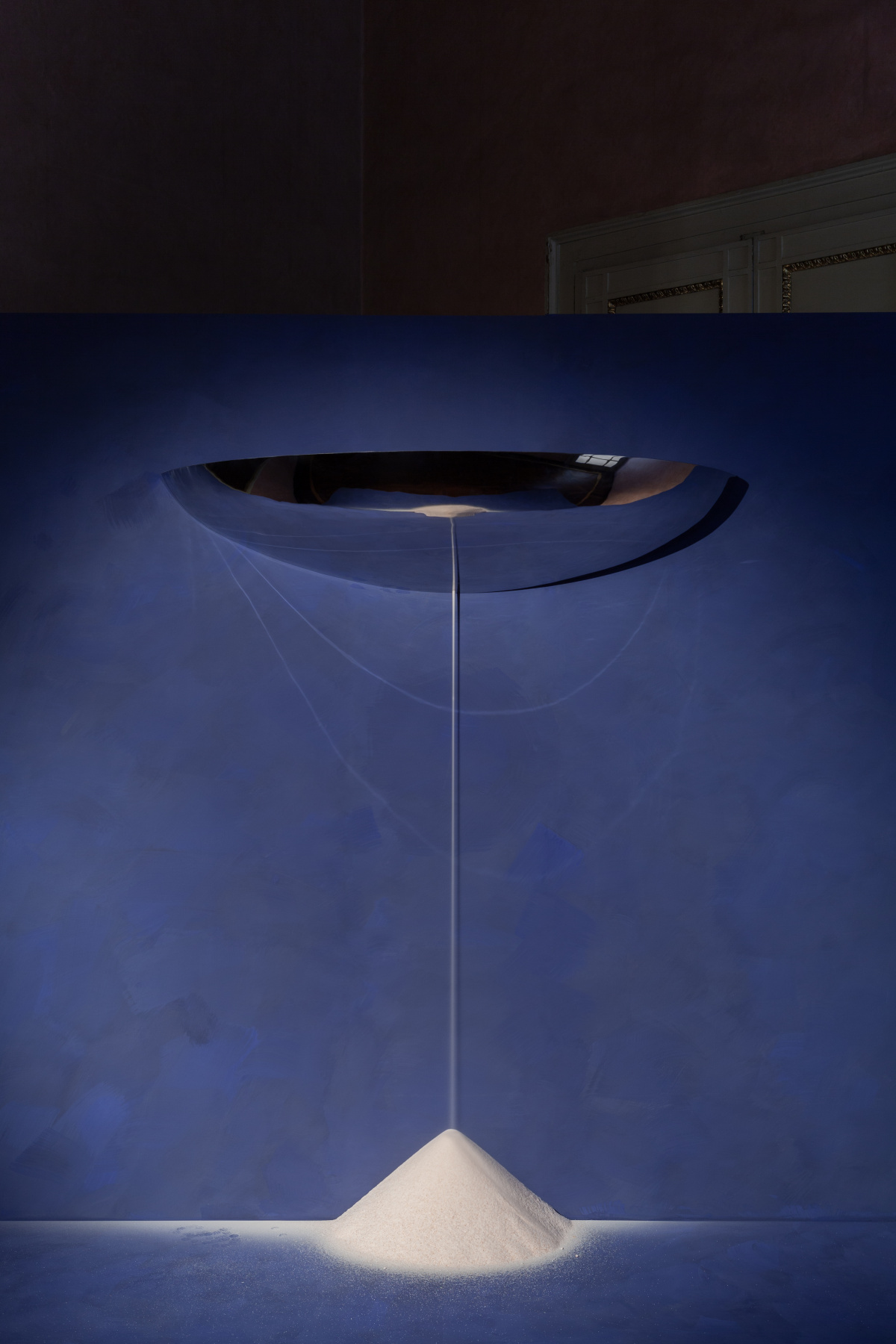

- Omi Iyọ by Nifemi Marcus-Bello exhibited at 5VIE at Palazzo Litta, Milan. The polished stainless steel references the bottom of a boat and acts as a mirror for reflection. Photo by Amir Farzad

- “The work is filled with salt,” says Anna. “Nifemi wanted to incorporate salt as an element because of the conversation he had with the Senegalese gentleman. He mentioned he couldn’t get the taste of salt out of his mouth for weeks after the journey.” Photo by Amir Farzad

Chris Force: Your focus is on collectible design and not as much the fine art world?

Anna Carnick: Definitely. The projects I’m drawn to always center around projects that have a social or environmental justice focus. That’s very important to me.

Given the contrast between the accessibility and career opportunities in the fine art world versus the design world, particularly for emerging artists, how do you perceive the evolving landscape for young artists today?

Nifemi Marcus-Bello: I think it’s the same with art and design. My practice is split into two—the commercial side and the artistic side. The commercial side exists for me to survive, where I’m speaking to and collaborating with brands to design meaningful products. On the artistic side I create art I feel I need to speak about. It should resonate with people, create dialogue, spark conversation—what good art does. I feel design should do the same as well. But if you’re monetizing design as a practice, it becomes tricky depending on the area you’re in.

In Africa being a visual artist is more lucrative than being a designer. In Europe and London my friends would say being a designer is a lot more lucrative than the art world. In America, depending on if it’s New York—art pays the bills, design doesn’t. Producing art is also cheaper. Design is heavily driven by finance and creating a prototype. Most designers would say artists are killing it. There’s no design work I know of that sells for $14 million. It’s also harder to get into design because you need funds.

Anna: The business of art and design is fascinating, and quite difficult. Most designers put a lot of puzzle pieces together to do work they want to do. There’s a bit of a balancing act.

Since the ’90s we’ve seen more narrative-driven design. Design and storytelling have become part of the zeitgeist, and more people are excited about it. The work I’m especially excited about offers personal storytelling that resonates on a broader level.

Does the creator’s intent for the work matter to you? Is the sincerity no longer there if you’re telling your narrative through something like a Nike collab versus fine art expression?

Anna: The work I focus on is collectible design, so it’s somewhere in the middle.

Nifemi: I find it funny that in the West, they emphasize not talking about money and art. They want it to feel like an afterthought. There are some things I will work on where I’m thinking of financial gain on the commercial side. If you collaborate with Nike, it’s a conglomerate that needs funds. If you’re designing for them, you have to think about it from a commercial, economically viable, product side of things.

Do you mentally draw a box around what is allowed and not allowed into your process on the fine art side of things

versus your commercial side?

Nifemi: There are conversations I want to spark through the work I’m doing. That’s the most important part for me. I want to tell the right narratives around material, production, my people, and myself. I’m happy I was able to bring this project here and not a chair, because I’m sure you’ve seen 1,000 chairs. I want people to understand there’s a social side to design as well.

Contemporary design looks like systematic thinking. If you’re designing a chair, why not discuss the system behind making it so another person doesn’t make the same mistakes? We should be sharing more information in the design world. Even when I research design across Africa, it’s something that’s inherently African. People are happy to share information on where things are made and create archives. Why would someone go to design school, research how to make the chair, and then come out doing the same thing?

I create art I feel I need to speak about. It should resonate with people, create dialogue, spark conversation—what good art does.

How did Omi Iyọ originate?

Nifemi: I had the opportunity to critique the Venice Architectural Biennale school. While touring with the students I had a conversation with a Senegalese migrant who told me a horrific story about his journey via boat from Senegal to Italy. After that conversation I realized I wanted to create something around migration to spark a dialogue.

Anna: The work is filled with salt. Nifemi wanted to incorporate salt as an element because of the conversation he had with the Senegalese gentleman. He mentioned he couldn’t get the taste of salt out of his mouth for weeks after the journey. When we showed Omi Iyọ at Design Miami, we used a white salt. Here in Milan we went with pink salt because in Senegal, there’s a beautiful pink lake where pink salt is harvested. It’s another way to honor them.

Over the course of the week the salt flows down from an aperture at the bottom creating a pattern of crystals below. It’s made from upcycled stainless steel that’s been highly polished. The idea is that we can each see ourselves and see our own reflection in the work. It makes you think about your relationship to those who make this very treacherous journey. It also makes us think about how we treat one another, and what each of our own roles is in relationship to this larger crisis. It’s really meant to spark a dialogue.

How did your conversation start with the migrant?

Nifemi: He walked up to me and was speaking the local dialect, Wolof, because he thought I was Senegalese. He was curious because he saw me walking students in and out of the Biennale. I think maybe he works there or lives there. It’s funny because he didn’t want to give me any information about himself. I don’t even know his name. I also felt I didn’t need that, so to speak. When Africans see each other, we tend to at least give ourselves a nod.

How do you view the role of beauty in making socially active work more accessible, particularly in contrast to narratives that may be considered visually challenging or “ugly?”

Anna: This is one of the things I appreciate and respect so much about Nifemi, because he creates the most beautiful pieces. His work is like an onion, you just peel back the layers. You are initially struck by the elegance of the aesthetics, the elegance of the pieces. As you go deeper the materiality tells one story, and the process tells another. He is brilliant and considers his projects from a single angle. Somebody can come in and appreciate it on a surface level, but if they are so inclined to dig in a little bit more, there’s a whole universe they can discover.

Nifemi: As a designer my job is to demonetize beauty. No matter what it is, the goal is for me to understand both the working class and high-class client. Even if you have $1 to produce an object, it has to be beautiful. And beauty is subjective.

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 12. Subscribe today