Chad Stone has always been a tinkerer. “I was born with a propensity to craft something,” he says. He loved building blocks as a kid; his first invention was an air-powered car, mapped out in detail on paper.

“Around the age of 8, I started drawing things to see if there was a better way. I’m impatient. If something seems like it is taking longer than it should, I try to find some way to improve it,” he says.

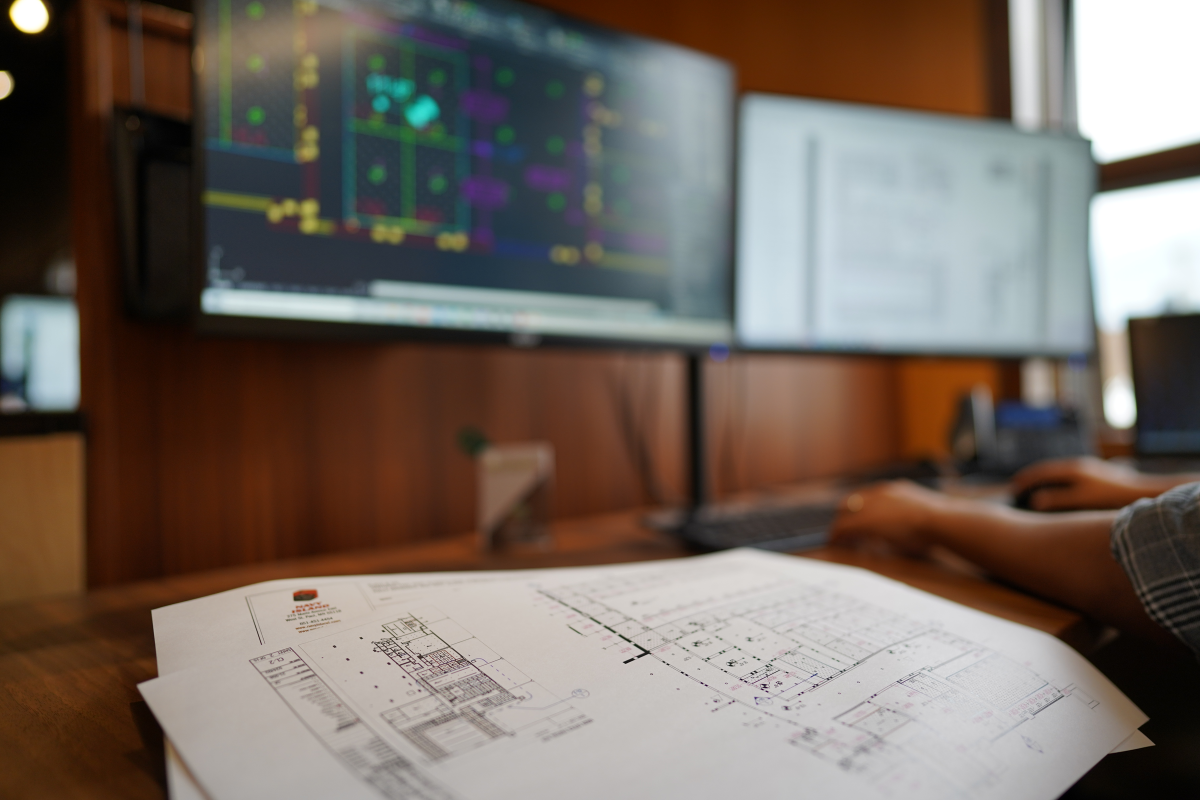

Chad likes to ask: “How hard could it be?” “It often gets me into trouble because I’ll end up working 24 or 36 hours straight on a problem I’ve started because I’ve got to finish it.” Photo by Fritz Kinney

Chad is the master inventor behind Navy Island, a Minnesota-based acoustic and architectural wood manufacturing company that holds multiple patents. It’s a family operation, one that started in a garage.

In the late 1970s Chad’s dad wanted to redo the family’s kitchen and bought woodworking equipment to carry out the renovation. He encouraged Chad and his brothers, Jeff and Ben, to explore woodworking in the garage. They started experimenting with building benches, a passion that grew long after their dad finished renovating the kitchen.

In 1983 Chad’s older brother, Jeff, started what became Navy Island while they were in high school; he was just 16. Chad, two years younger, joined his brother in the business, which at that time was focused on restoring furniture locally. Over time their furniture refinishing business morphed into cabinet and millwork finishing, which eventually morphed into other new products. “We had a constant awareness that doing one thing is OK, but let’s keep trying other things. We moved through finishing into contract finishing for other cabinet shops. At that point I was getting really good at finishing technology, so we developed a line of manufactured kitchen cabinet doors. That went poorly, so we transitioned into architectural wood plywood and acoustic products.”

- Photo by Fritz Kinney

- Photo by Fritz Kinney

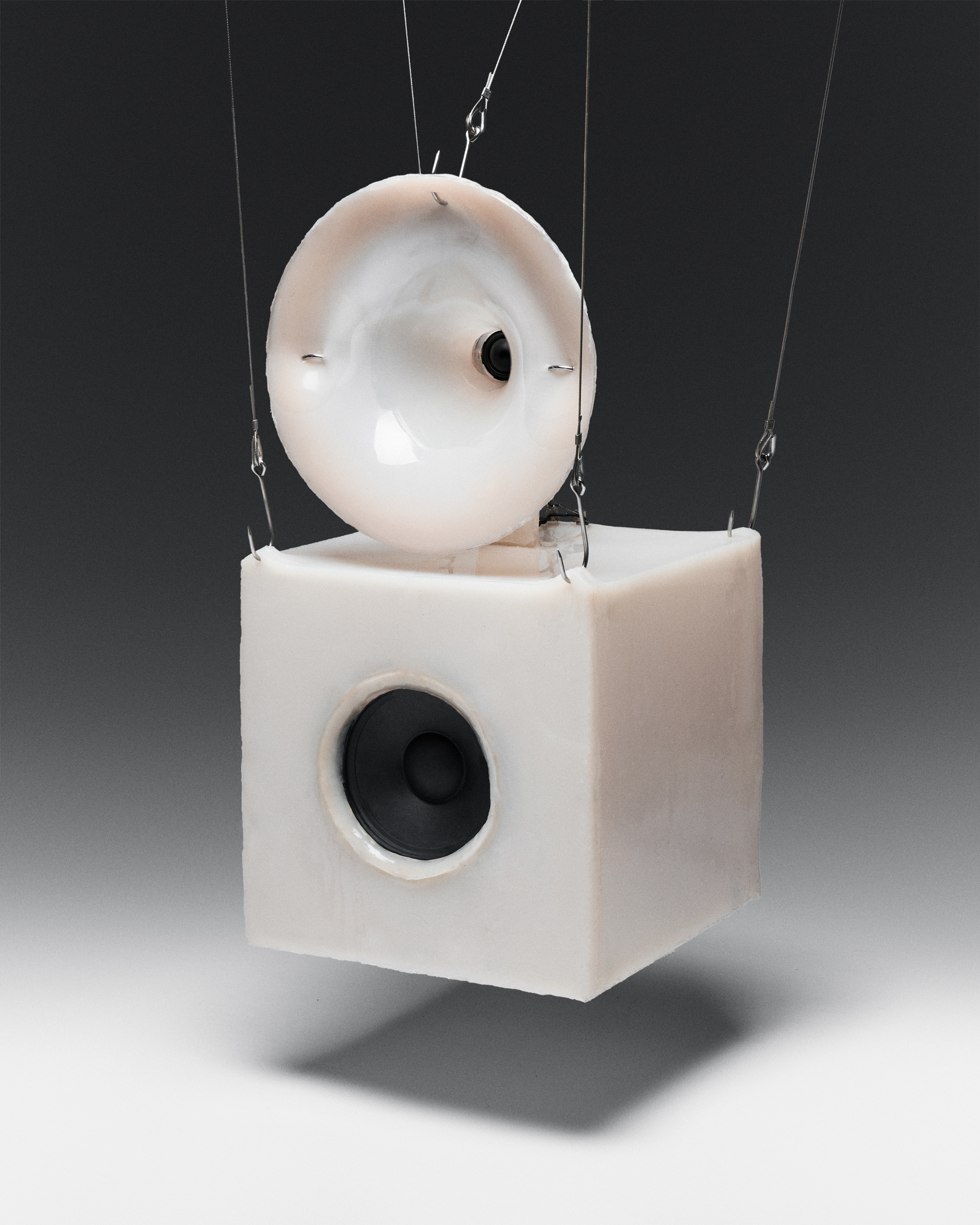

SoundPly was an innovation Chad says the team stumbled into on accident. In 2012 a client asked if they could develop micro-perforated acoustic panels, a type of sound-absorbing panel with thousands of tiny holes—up to 30,000 per square foot—across its surface that help minimize noise. They went for it. Little did Chad know how hard designing an acoustic panel process would be. “It was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do. If we had known how tough it was, we may not have done it.”

Micro-perforation acoustic technology was developed in the 1970s, when scientists modeled, tested, and verified the best configuration for these tiny holes to absorb sound. Because the sound-absorbing pattern had already been established, Chad’s work focused on the design of the panel itself—namely that he wanted the effects of the panel to be heard and not seen—and how to manufacture it successfully. He was aiming for an acoustic panel that not only absorbed sound efficiently but also one that could hide perforations in plain sight, where people could look at a wall or ceiling and not even recognize that acoustic panels were there. Chad also had the added challenge of developing a manufacturing process that could produce more than 100 panels a day.

Because Chad and Navy Island had never developed an acoustic product before, the design and manufacturing process made for lots of trial and error as they tested various designs and manufacturing methods. Early versions of this new acoustic product were crude, but Chad kept tinkering. They worked with a manufacturer in town to create prototypes, tested them, and when they didn’t work, went back and started the design process all over again.

It took six months, but Navy Island finally had production-ready panels. The result was SoundPly, a wood veneer acoustic panel that even with thousands of tiny perforations looks like solid wood. Aesthetics aside, deeper into the panel there is a patented arrangement of fibers that leads to exemplary acoustic performance. SoundPly acoustic panels combine two types of sound absorption—porous and resonant—which Navy Island says make them the world’s quietest acoustic panels.

The Rensa Lit Baffle—a versatile, modern lighting and acoustic solution—was designed to complement SoundPly acoustic baffles, planks, and panels for a total room solution with matching real wood finishes. Photo by Fritz Kinney

After all the time spent developing SoundPly, when the process was over, the whole team was left with a feeling of, “Now what?” “My brother said, ‘I think there’s a much bigger market if we could make the panel into features for walls, ceilings, doors, and luminaires,’ so then we launched into the full package with a variety of backloadings, acoustical cores, wood veneer finishing services, and more recently Rensa Acoustic Lighting. That’s where we are today.”

SoundPly in Action

Take a walk on the Yale University campus, and you’ll stumble upon the new Yale Schwarzman Center, where you can see 15,000 square feet of Chad’s hard work on SoundPly on the ceiling of the Commons.

Built in 1901, the building commemorates Yale’s 200th anniversary and is a cluster of Beaux-Arts style buildings designed by Carrѐre and Hastings—the same architects behind the New York Public Library and many iconic early 20th century buildings. Despite its architectural significance—high vaulted ceilings, large polychrome and decoratively painted heavy trusses, molded brick, and heavy wood paneling—and ample space to sit, eat, and decompress, the Commons has been used mostly as a dining hall. At times it’s held formal dinners, concerts, and other special events, but these were always hampered by poor acoustics.

Because of the building’s grandeur, Yale wanted the Commons to play host to many more events, from concerts to dinners to lectures, so the university set out to transform the Commons into a flexible performance space. The only problem: due to the size, height, and openness of the room, the acoustics were all wrong. You couldn’t host a concert or lecture or allow for any amplified noise beyond student chatter.

“There was lots of reverberation in the room because the Commons is very tall with brick finishes, terrazzo floor, and lots of wood,” says Russ Cooper, principal consultant at Jaffe Holden Acoustics, who consulted on the project. In other words, these are hard materials that reflect sound and increase noise. Carpet wasn’t an option—though it can dampen sound in a room, the space is still used as a dining hall during the day, where the opportunity for messes and stains are abundant. The walls, too, were an issue. Fabric curtains that could lower noise levels would also cover the ornate architecture the team was trying to preserve. In the end, “the ceiling was the only way to improve the acoustics,” Russ says.

So Russ and his team researched the best acoustic panels available that could not only lower the reverberation but also blend in with the turn-of-the-century ceiling.

After rounds of testing, including holding a mock concert to compare products and noise levels, they landed on SoundPly. Russ brought their findings to the team at Robert A. M. Stern Architects (RAMSA), the architecture firm behind the project. “Navy Island jumped out in the beginning because they had this micro-perforation technology that made the perforations invisible to the naked eye within 3 feet and blend into the original ceiling, and they met the criteria we needed to meet acoustically,” says Kurt Glauber, associate partner at RAMSA.

Look up at the ceiling in the Commons, which reopened in the fall of 2021, and you are looking directly at custom-stained Southern Yellow Pine SoundPly planks that match the original wood plank deck. From the floor, the micro-perforations, which provide the acoustic performance, are not even visible. “I’ve gotten up on the catwalk and still can’t tell the micro-perforations are there,” Russ says. The original solid wood plank ceiling lasted for more than 100 years. The SoundPly planks are designed to last another 100, preserving the historic legacy of the Commons.

Chad is the master inventor behind Navy Island, a Minnesota-based acoustic and architectural wood manufacturing company that holds multiple patents. Photo by Fritz Kinney

Looking back on the SoundPly design process—something Chad does “not so fondly” because of its complexity—he acknowledges that the difficulty he went through in its development was just part of the process. As with any design, when you see the final result, it’s shiny and new, but the “the truth is that it’s much dirtier than that,” he says. “When you try to build something using wood and metal, there is debris, sparks—I look like a nutty professor covered in chemicals. The inventing process is more about accepting failures than being successful. The faster you can fail at something, the closer you can get to being successful.”

Likewise for the Commons, it took multiple failures testing other acoustic products before the team found success with SoundPly. “Everyone realized from an early stage how important the project was to Yale and the building’s integrity, and no one lamented the details. We all worked hard to maintain the historic character of the building,” Kurt says. “SoundPly was just one piece of that puzzle but a big one. And though students and visitors might not be able to see the acoustic transformation, they will be able to hear it in the quiet—and that’s exactly the point.

Photo by Francis Dzikowski/OTTO

Prior to SoundPly’s installation, the reverberation time, or how long it takes sound to decay in a closed space, in the Commons was measured at 3.2 seconds between 500 and 2000 Hz. After SoundPly, that reverberation time reduced to 2.3, 2.1, and 1.7 seconds at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz, respectively. “That may not seem like a lot, but cutting reverberation time by a third is significant for such a large space,” says Russ Cooper, principal consultant at Jaffe Holden Acoustics. In fact, the reverberation time dropped even further than the project required at 2.3 seconds, perfectly falling within the 1.8 to 2.2 second standard for concert and performance spaces. “Now they’ll be able to have jazz bands, rock bands, show movies, dances, lectures, and so on all in that room.”

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 07 with the headline “The Sounds of Silence.” Subscribe today.