On a Tuesday morning, the top floor of Pentagram’s Manhattan studio is reasonably quiet with a few staff milling about, yet the loft-like space radiates an undeniable energy. At this address, brilliant ideas are born, be it a brand’s logo, a corporate identity, or a well-curated exhibition.

Dramatic from the soaring ceilings to the low-slung leather sofas, the second level of the two-story design office—which occupies the 11th and 12th floors of a Neo-Gothic building on Park Avenue South—has not a hair out of place. I’m here to interview Natasha, who’s worked on projects for big players like the Guggenheim Museum, Kate Spade, Chanel, and Nike, among many others.

As a child, the walls of her family’s Taipei home acted as her canvas, and colored pencils, crayons, and watercolors her media. That childhood imagination inspired her to study graphic design at New York’s School of Visual Arts, eventually working for the likes of Base Design and Stone Yamashita Partners, followed by a stint running her own firm, Njenworks. In 2012 she became the youngest partner at Pentagram—the largest independent design studio in the world and a place she defines as “her frontier.”

- Photo by Josh Andrus

- Photo by Josh Andrus

Even with years of success in graphic design, Natasha still finds the field enormously interesting. And after living in New York for two decades, she hasn’t lost sight of her Taiwanese heritage, continuing to think of herself as “a kid who grew up in Asia”—a part of her she says will never go away. She believes in working hard, especially in the early stages of a career, and says that’s the greatest lesson she’s learned.

After a short wait, I slip into a sleek modern side chair pulled up to a round table in a modest conference room overlooking the Flatiron District’s motley rooftops and surrounding skyline. Ten minutes later, Natasha glides in gracefully, donning skinny black pants, a crisp white chiffon blouse, and white chunky-heeled pumps with pointed toe boxes. She expresses an intensity, yet she’s approachable. Clutching a Starbucks Venti iced coffee before sitting two seats away from me and smiling, Natasha is eager to chat, and we dig in.

What’s your earliest memory of art?

As early as 2 or 3 years old. I always liked to draw as a kid. I was naughty at that time and wanted to get the biggest canvas. I used to draw on the walls so my mom would give me a bigger sheet of paper. I’d get behind furniture and find a little corner and draw something there and then hide it. It was impulsive.

Photo courtesy of Pentagram

Pentagram created a new brand identity for Van Leeuwen. They removed the visual noise typically seen in ice cream branding, using minimal graphic elements and a decisive color palette to reflect the purity of the ingredients and colorful pints that stand out in stores and look great on social media. Photo courtesy of Pentagram

You’ve spoken about American culture in design and how so many people are driven to be individualistic, and how that clashes with your own ideals. Can you explain how collectivism has impacted you?

There’s a profound difference in Eastern culture, I mean Far East or East Asia, where we value other people’s happiness perhaps more than our own. We’re always thinking about how other people feel. For example, politeness comes through in this society. Whereas here (in the US), the idea of happiness is individualistic in pursuit that you are the hero along this journey. You are going to build your own happiness.

When I first came here (to America), I struggled with it a little bit. I felt as a kid coming from Asia to New York, all of a sudden I felt invisible because I didn’t have the “me” in me—always thinking how I could please other people. That’s how we were brought up. I didn’t have enough “me” to stand on my feet. I couldn’t change it overnight. Going to school, learning, making friends, and after many years of immersing myself with the people here, I started to discover me. Creating this “me” I didn’t know existed.

“It’s really critique that makes design meaningful to any given context. Anything needs critique, not just design. Policy needs critique. Our government needs critique. Anything. Everything.”

What’s your day-to-day like at Pentagram?

I like to get here earlier than anybody else. I typically arrive at about 8:30 or 9am, so I have a half-hour or hour to myself. I go through emails and check today’s news. The day is packed with different types of meetings and engagements with people. It can be something as nerve-racking as a design presentation—the first time to unveil the work and you don’t know how the client is going to perceive the work. I do a lot of preparation for those types of meetings. Sometimes it’s a new business engagement. I have meetings with my team here, review designs in different stages. Internal meetings are a lot less formal; we gather around my team’s computer.

I leave sometimes at 7pm and sometimes at 8pm, but there isn’t a clear cut-off time for me. I continue working at home, researching on the internet, surfing, looking at new things, reviewing designers’ work. It’s around the clock. I don’t draw a clear distinction between work and life.

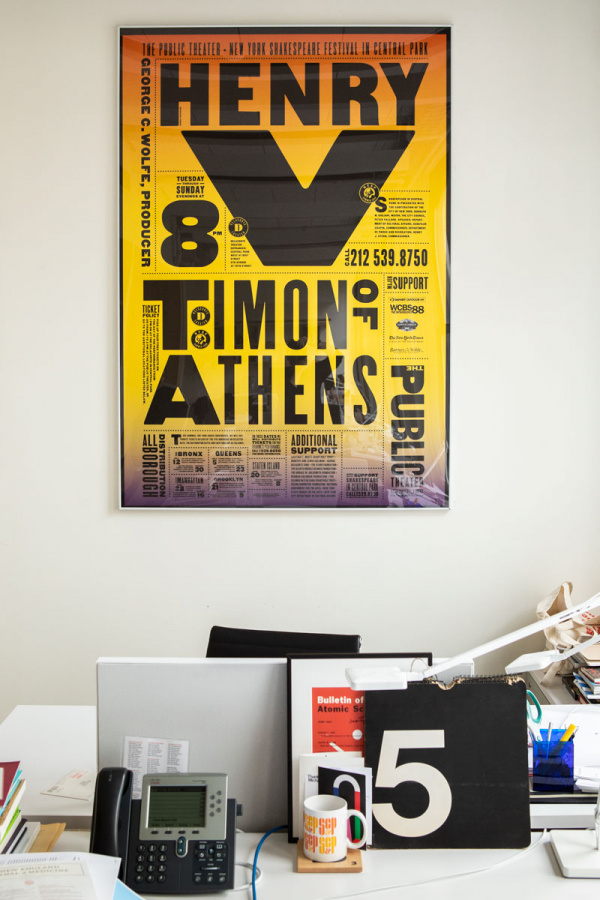

Natasha’s work covers everything from brand identities and environmental design to multi-scale exhibitions and interactive graphics. Nike, Harvard Art Museums, the Guggenheim Museum/Foundation, Target, Puma, and many more have turned to her for her sharp eye and creativity. Photo by Josh Andrus

In the last year, how many days off did you take?

I travel a lot to give lectures at conferences. Each time I travel to a new place I haven’t been before I see it as a mini-vacation because there’s all that newness to explore even though my stay is usually very short. Sometimes it’s three or four days. I don’t keep a record. I can actually work on vacation. I have Slack on my phone, and I’m on Slack with my team. And I’m not bothered by that.

What’s the best part about your job?

It’s the ability to be able to be creative yet be analytical at the same time. There are different creative fields. Some fields require total creativity. It’s a kind of freedom. Certain creative fields require total discipline, such as user-experience design, which is about functionality, understanding cognitive systems (how people think and behave). But graphic design lands right in the middle. It’s a field that requires total creativity, meaning you have to really think about something that can be new, exciting, meaningful, and inspiring, yet you have to be analytical of the given context. These two ends are polar opposites, but graphic design is really interesting because it sits in the middle, similar to architecture.

Pentagram designed a brand identity for the LOROD fashion brand that captures its unique mix of high and low, refined craftsmanship, and utilitarian functionality. The project encompassed the brand’s messaging and art direction of its fashion photography as well as website design. Photo courtesy of Pentagram

What part could you do without?

New business pitches. I think I am a pretty good salesperson when I am promoting our work, but new business pitches are different in that you are in a position to try and get something and that is an inferior position. There is still the service provider relationship in that, and when you start working, these two parties become more equal, but when you’re trying to get the job, you’re in a more powerless position. You don’t understand everything that’s happening on the client side. You don’t know how they are going to make decisions. You don’t know who you are competing with or their criteria. All of that unknown—you have to put it aside.

Tell me about your team and the way you work within Pentagram.

I have 12 people on my team. Pentagram New York has about 125 to 135 people in the New York office, and we have eight partners. Each partner runs a team. We’re known for being small. Pentagram is a really interesting business structure, sort of like the US. Each state has its own state and law, and each state is quite different, but when the states come together, you have the federal level, and that’s Pentagram. Each partner governs a state. Each state produces very different work. It’s a true celebration of design democracy and a place that celebrates creativity.

Designers know which team they want to work with because each team’s work is so different. As a whole, our portfolio is so diverse it’s confusing to people. People think, “What do they do? They do a little bit of everything.” The total portfolio is a collection of different partners and teams.

You’ve worked with huge brands, from Nike to the Guggenheim to Chanel. What is the biggest challenge when it comes to working with well-known brands?

The scale of the business is not the determining factor of the relationship. Every organization is organized differently. It’s really how the client group works. We could be working with a large global brand. If we are working with the C-level decision-makers, the process can be really smooth and good. But it could be a startup, and a lot of cooks in the kitchen can complicate the process. It all depends on the decision-making process on the client side. I try to understand that clearly before I commit to the project. Half of the success of the project is how we can manage their decision-making process.

Photo courtesy of Pentagram

Photo courtesy of Pentagram

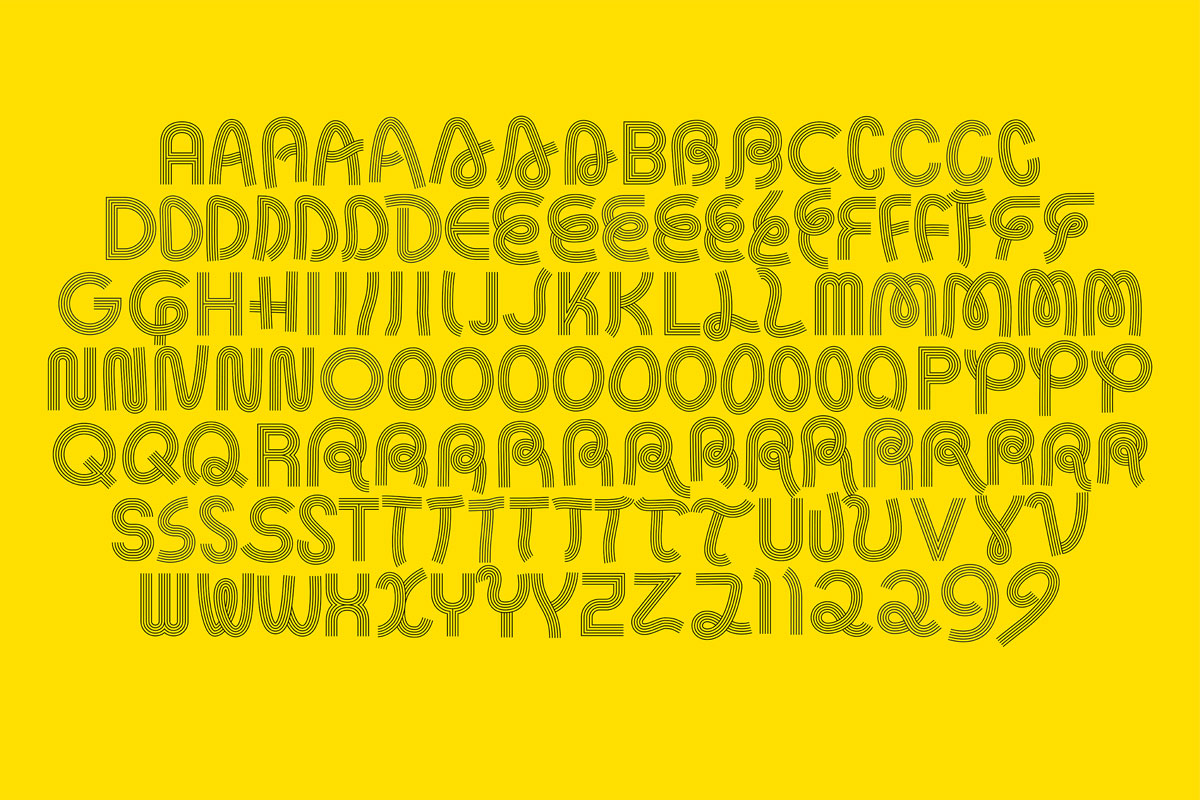

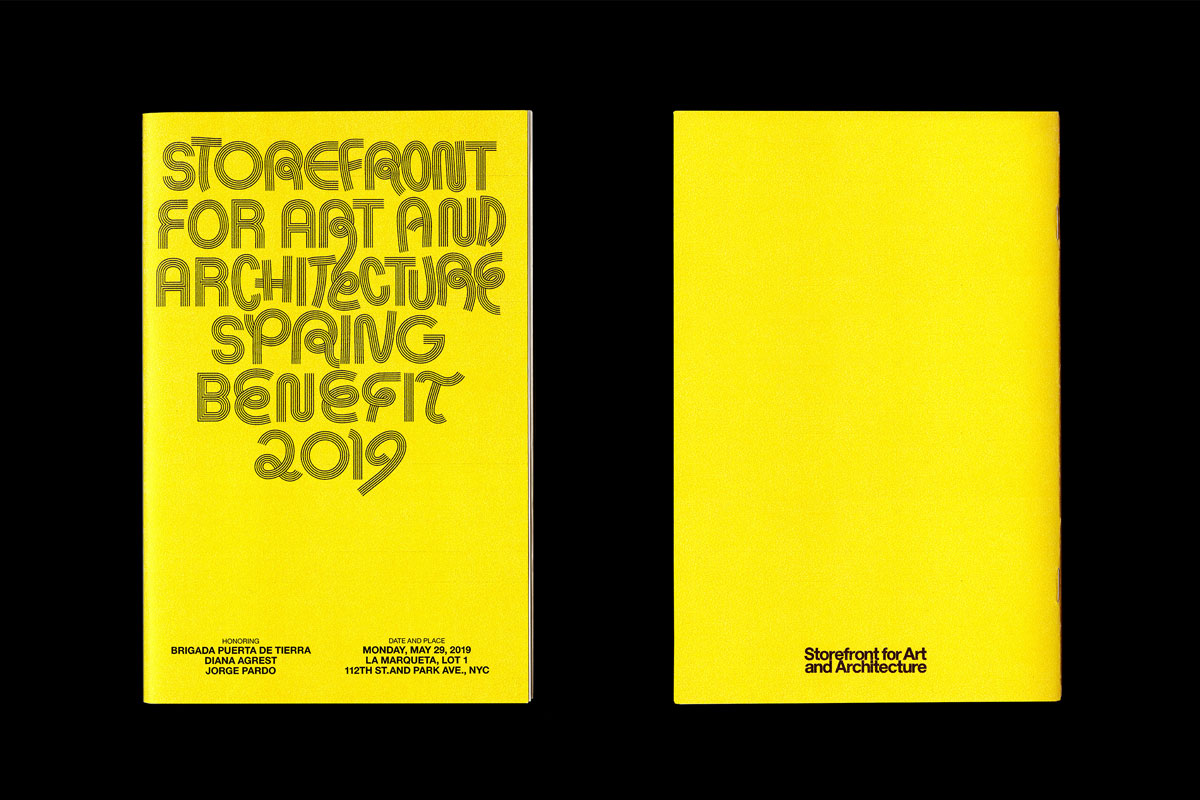

Pentagram designed the branding for the Storefront for Art and Architecture’s 2019 spring benefit with a custom typeface and vibrant yellow. Photo courtesy of Pentagram

Do you have one rebranding success story that stands out?

We did a brand refresh of Esprit. It‘s a brand that resonates. People say, “That’s my favorite brand!” Expressive, and all those cool colors, patterns, Memphis style. It really resonates with anyone before the millennial generation. In the last 10 years, there’s a lot that happened to the brand. They moved out of the US market and concentrated in Europe and Asia. The brand evolved from the early days of Esprit (when the brand was exuberant) to something a lot more casual. Last year, new CEO Anders Kristiansen joined, and he is in charge of renewing the Esprit brand, but thinking how to make this renewal contemporary. So it’s not a straight-up revival project. If it would’ve been a clear revival project, it would have been a lot easier. We understand their design language, but how do you recognize the heritage and design attributes from the 1980s and ’90s and make the brand feel contemporary today? The design elements are still there in the archives. They got rid of old logotypes and replaced them with clean, san serif fonts in logos.

There’s a trend in reduction. Esprit was more is more, and today it is less is more. We needed to recognize the elements that are essentially Esprit. We reworked the stencil typeface. That began the core of the brand tool kit. There are elements and applications that need to stay simple, and other touchpoints that need to be a lot more expressive. For example, posters, campaigns, e-newsletters, so we created a scale from very simple, very minimal to very expressive, so the brand can choose the right situation to use the right language.

- Photo by Josh Andrus

- Photo by Josh Andrus

What else are you working on right now?

We are working with a startup bank. We are creating the identity as well as the messaging and copywriting. When you think about the category of financial services, you think about the old-school banks, legacy banks. And then there is a whole group of startup financial services, be it banks, apps, etc. And they all have a tendency when it comes to their branding. It’s more about the product experience and less about the identity. We are saying, “You are building a bank for the next 100 years, so we need to transcend both categories.” Our client is collaborative and open-minded and curious about design. We can have fruitful and interesting conversations with them. Typically financial institutions are not necessarily the most fun to work with. Constraints become a lot greater, but in this case they don’t want to be dry or boring or the typical startup. They don’t want to be perceived that way. We have a clean, blank canvas that’s really exciting.

Photo courtesy of Pentagram

Pentagram collaborated with FR-EE / Fernando Romero Enterprise, BuroHappold, and SuperUber on the design of “Border City,” the Mexico installation at the inaugural edition of the London Design Biennale, presented at Somerset House. Instead of a wall, the exhibition proposes a concept for a truly binational city that offers a new model for a rapidly developing world as populations grow, migration increases, and economies continue to globalize. Photo courtesy of Pentagram

Have you ever turned down a project?

We got an inquiry from a startup that utilizes factories in China who make premium products for premium brands like Prada and Louis Vuitton. The startup would work with these factories to create the same products without the logos of these brands and sell the products on their platform for a fraction of the price. To me, that is plagiarism. That is absolutely immoral. I have a very strong stance about intellectual property. I declined that project, and I didn’t even speak with the founder. I question the ethics.

You’ve said design thinking is “bullshit.” What does that mean?

“Design thinking” is a five-step process—empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test—and claims to guarantee that you can create satisfying solutions. I am against it. I think it’s idiotic. It’s not how people’s brains work. Design is very complex. The process should be defined by a given situation. There’s no magic potion that will solve every problem equally well. Design thinking fails at addressing design problems. The formula itself is the answer. A lot of big companies sell design thinking as an educational package, but I stand behind my belief.

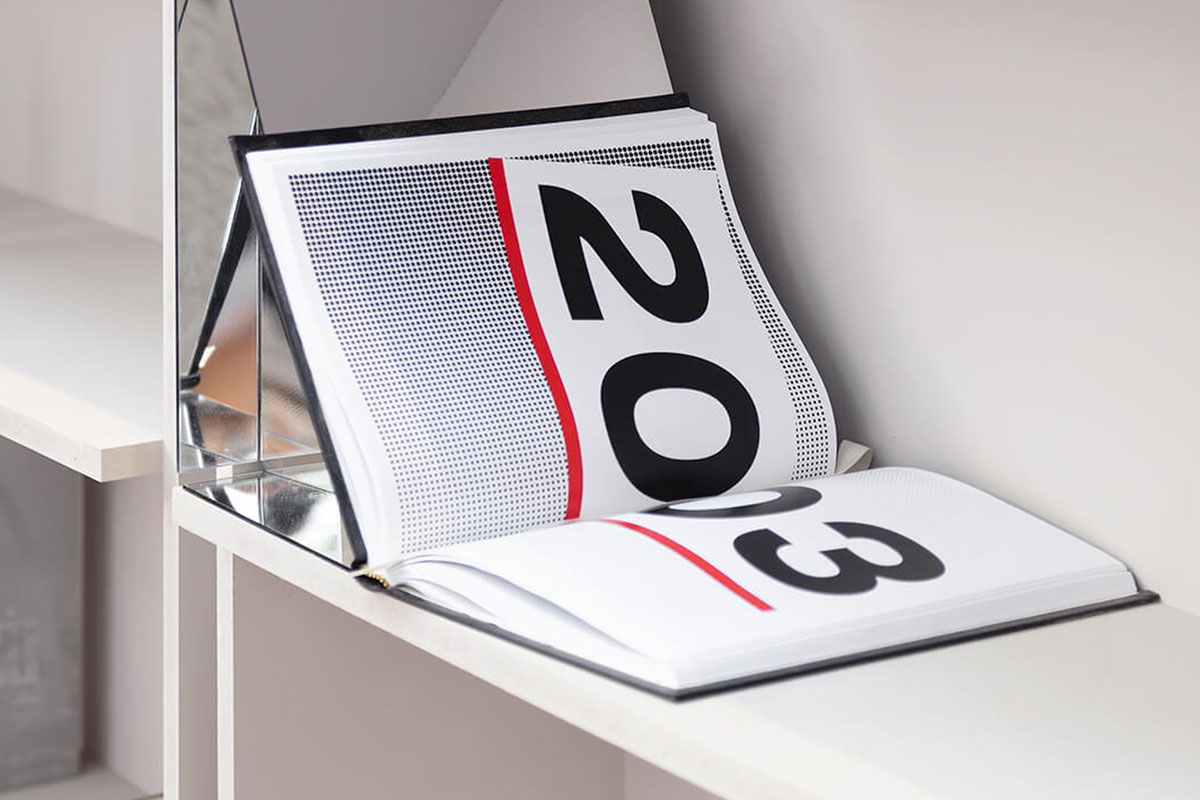

Natasha and her team designed the brand identity for the first New York Architecture Book Fair, held in 2018. The branding centers on typography and rectangles that suggest the spines of books. Photo courtesy of Pentagram

Why is critique so important during the design process?

If there’s no critique, then it’s a free-for-all. Anyone can do anything. It’s really critique that makes design meaningful to any given context. Anything needs critique, not just design. Policy needs critique. Our government needs critique. Anything. Everything.

Do other designers inspire you?

A lot actually. There’s an architecture firm I really admire—MVRDV. They are based in Amsterdam. It’s a Dutch design firm. Their work represents this idea of being incredibly free and expressive yet incredibly disciplined and critical. They are the perfect representation and it’s a mystery to me how they are able to do that. It’s a joy to look at their work.

I hire designers who are really excellent designers. They all inspire me in different ways. Each of them has something special about them, be it a certain skillset that other designers don’t have or sensibility that’s distinctive from others, be it a knowledge base about the world that other people don’t have.

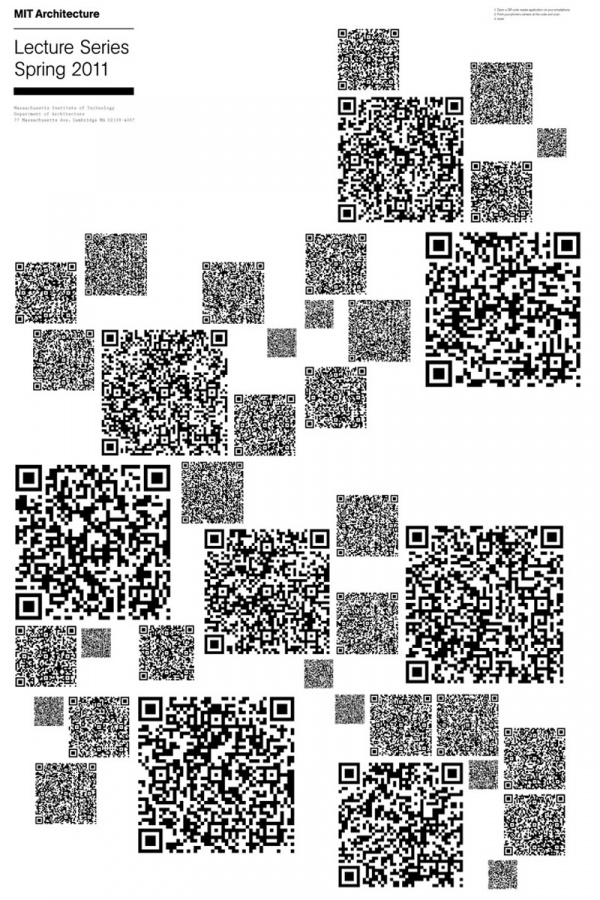

- Natasha designed this poster for the MIT Architecture Lecture Series in spring 2011. Photo courtesy of Pentagram

- Natasha Jen and her team designed TransFoner, an interface for Android phones that re-imagines apps as a kit of parts in constant transformation. Photo courtesy of Pentagram

You’ve said you still have doubts about your career at times. Is that something everyone deals with?

Having uncertainty about your trajectory is necessary because it forces you to think about what is your own frontier. Most people look at careers as a ladder-climbing process, meaning how do we climb up economically? Or how do we climb up in terms of job titles?

It’s not that I am not sure about being a designer. It’s not that I want to become an accountant. But I am still looking for my frontier, and that changes as you get older and that is the only way to produce interesting work. What is the next frontier? It can be graphic design. It can be architecture combined with graphic design. As a designer, you need to define your frontier.

[rp4wp]

Have you seen the role of women in design change?

I think women face the same age-old challenges—how to balance the advancement of your career with your family, that is childbearing, raising children, being a mother. Women sometimes have to make really hard decisions choosing one over the other. And many decide to choose their family, so their work stops at a certain point. That’s why you see fewer women in design leadership or leadership in any field. I don’t have a solution for it; it’s such a complex challenge. We need to prepare, as a society, better mechanisms so families and children are taken care of in some way. As a society, we don’t have that. Can we imagine a place where women can bring their kids to the worksite? I am talking about a utopia. If we build a society with these mechanisms, then we don’t have to make these impossibly hard decisions. I have this fantasy that when I have a baby, I will bring my baby to work every day until that baby goes to school. The baby will sleep right here with me. That’s a great design project. From policies to space to labor to training people to run these centers.

How would you define “success” as a designer?

To be able to identify what you’re really good at. Either find a job that allows you to do that or build your own version, build a practice out of that.

Is there life after Pentagram?

That’s too far ahead. Pentagram is still my home. Pentagram is still the place where I think the frontier is and the frontier can still be defined here. The cool thing about Pentagram, philosophically and operationally, is that it has stayed the same for almost 50 years. It’s that philosophy and the economic business model driven by the philosophy that makes it a place to change and evolve and be exciting. It’s very unique.

This article originally appeared in the Fall/Winter 2019 issue of Sixtysix with the headline “Natasha Jen.” Subscribe today.