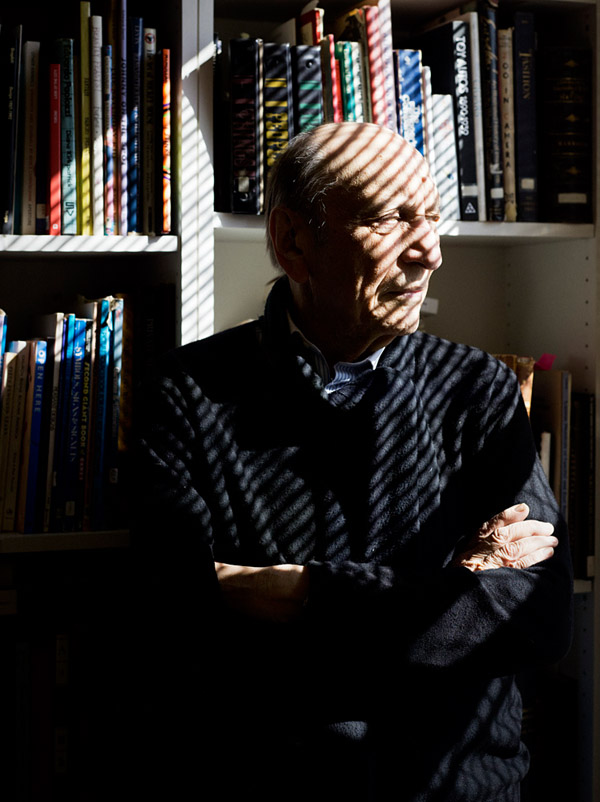

Design icon Milton Glaser is best known for his earliest work. Co-founder of the oh-so-famous Push Pin Studios, he made his name in the 1960s as an illustrator designing psychedelic-style posters. He’s written books, created magazines, runs a business, and has been teaching for 50 years. He’s the creator of the ultimate city mark—the “I Love New York” logo. But trying to pin down this design celebrity’s talents would be a major mistake. Because the 83-year-old Glaser nearly got pigeonholed once, and he’s never letting that happen again.

One of the things that has earned you accolades in your career has been your inclination to go against the grain. You launched New York Magazine in 1968, before anybody else was making city magazines. In 1987, you redesigned all the graphics for New York’s iconic Rainbow Room to make it look like the fantasy nightclubs projected in Hollywood movies. Have you always desired to be different?

I’ve always been driven by the idea that it’s possible to occasionally produce art in the realm of design. Every once in a while the utilitarian function of design can also embrace a metaphysical one. Those are the jobs that mean the most to me. But don’t blur those together into one lumpy mass that doesn’t help you understand what you’re doing. You can’t be an artist in the design field. The very nature of producing art—which is about transgression, and invention, and the new—can prevent you from communicating clearly, and that’s too much of a burden to carry when you’re designing a beer bottle. There’s only one place to begin, and that is with solving the problem. A designer’s work is bound by utility and by the needs of a client. If you can do that and at the same time introduce art, then great. But that’s few and far between.

So, you’re practical?

Oh. Well, you can’t be in the field if you’re not practical. If you think that design is about self-expression, then you’re out of it. Unfortunately, there’s so much bullshit about self-expression and artistry and the rest of it, that it confuses people. It confuses teachers, it confuses schools, and it confuses everybody in the field, because they’ve not made this distinction clear enough to themselves.

When you walked away from Push Pin Studios in 1974, it was because you felt like you were becoming “lodged in history,” and needed to do different things. You said you were becoming “imprisoned by its reputation.” Why, and how, have you been able to escape this feeling?

What happens in professional practice is like what happens in movies. People are selected to do what they have already done; it’s a typecasting that occurs. Whatever that characteristic may be, when people become good at something, they’re doomed to repeat it forever. The great thing that an artist has, is that he or she can follow their own obsession, and move toward what they do not yet know. I’ve had that experience over the last five years with rugs and textiles that I’ve been doing. These are new experiments in color and form, and are done independent from a client or audience. That’s a very different experience.

“If you think that design is about self-expression, then you’re out of it. Unfortunately, there’s so much bullshit about self-expression and artistry and the rest of it, that it confuses people.”

—Milton Glaser

You’ve benefitted from the relationships you’ve had with so many talented designers throughout your career. How do your peers inspire you?

Well, I can’t say that I can answer that, in terms of pushing. I don’t need to be inspired.

But now you’re working with designers who are much younger, who were brought up using the computer, which is so different from the way you were trained. What happens here? Is there a push-pull?

Well, I’ll tell you how it works. I now say that I know how to use the computer, and that I’m not intimidated by it. That’s because I never touch it. I work with somebody else here who is proficient. I say, ‘Okay, let’s start. Just give me a red square. And take this thing and move it over here. What do you think of that? Too big. Okay.’ It’s like dancing—you have to have a good partner, and you have to know how to lead. And since I have ten times the experience of the person who is working with me, there’s no question about who’s leading the dance. But if the person that you’re leading isn’t a suitable partner, then it’s unpleasant for us both, and not fun to watch.

You pull up a chair and direct them?

When you run an office, you have to assume the responsibility that everything that goes out of the office is something that you’ve had something to do with. The core of the office is my vision, my history, my ideas. It can’t be any other way. You know, I don’t have any hang-ups about the computer. The only problem I have is that it’s badly used. The computer is the most powerful tool that a designer has ever had. It likes to do certain things, and it doesn’t like to do other things. It dominates the designer. That’s why when you go to a school, you see that young designers’ books are all coming out alike—because they’re all coming out of the same instrument. Young students don’t have enough training before they get to the computer and they use it to compensate for lack of knowledge and authority and judgment, and then it’s tragic. It’s had a bad effect on the profession, because it allows poorly trained people to get into the field and produce ordinary work. It’s like trying to produce music without having mastered the piano. And incidentally, this is a dead argument—people have talked about this endlessly, but we don’t really have a way of dealing with it.

Do new clients ever come to you not knowing who you are?

What people do now—which is pathetic—is that they will look up 20 designers and call them all and find out what they would be charged for a logo, and then pick the cheapest one. Frequently, I suspect, when we get such inquiries, they have no idea who we are.

How do you respond?

Well, it depends on the request! One of my rules of the universe is never work with someone that you don’t like. I’ve violated that principal, and every time I’ve done it, I’ve been sorry.

So you’ve learned your lesson?

Up to a point.

Will you ever retire?

I don’t understand what people mean when they talk about retirement. Retirement from what?

To golf ?

Golf? Oh, what a nightmare! No. That’s not my intention. Life has its own way of telling you its intention. I don’t plan to retire, but I recognize that there’s a certain point. You could lose energy, or you could run out of ideas. But that hasn’t happened. Actually, I’m doing the best work I’ve ever done in my life over the past four years.

Have you ever wished for a less recognizable name?

Well, if my name were linked with one specific thing, then I would worry. But I’ve managed to be obscure and peculiar in my production, so that people don’t even know anymore exactly what it is that I do. I’ve always followed my own interests, and I’ve always been very conscious of not getting pigeonholed, ever since I was a young practitioner. I saw what happened when you became specialized, and I didn’t like that. It’s partially philosophical. I don’t believe in too many things. I’m not an ideologue. I don’t believe in the truth of any singular pursuit. My favorite quotation is ‘Belief is the closing of the mind.’ And that pertains to my work, very much.

—

The Nine-to-Five Skinny at Milton Glaser, Inc.

Just because he’s 83, don’t think Glaser has lost any speed. in March, he announced the launch of a new line of hand-woven rugs designed exclusively for carpet manufacturer Lapchi. Textiles are a new field for him, but in the spirit of staying fresh, this venture is no surprise. Of course, Milton still churns out regular graphic design work, too. “On Mondays, we do a cover for The Nation,” he says, referring to the country’s oldest political weekly magazine. “We get a brief in the morning, and we finish by 5:00 pm.” With all that Glaser has going on, no wonder he’s not too interested in golf.

(Originally published in Design Bureau in 2012)