Sigurd Bank is not sure if he’s actually interested in fashion, a surprising answer given his company, Mfpen (a Danish term for signing on someone else’s behalf), is quickly becoming one of the most sought-after menswear brands in the world. The company began as a project in Copenhagen, squeezed in between Sigurd’s other two jobs—one as a trained production manager and designer, the other pouring beers at a local pub at night. Like many success stories, he had good timing, starting the label just before COVID-19. He was able to ride the e-commerce boom and hire his first employee. He now runs a team of 13, including production, development, and store staff.

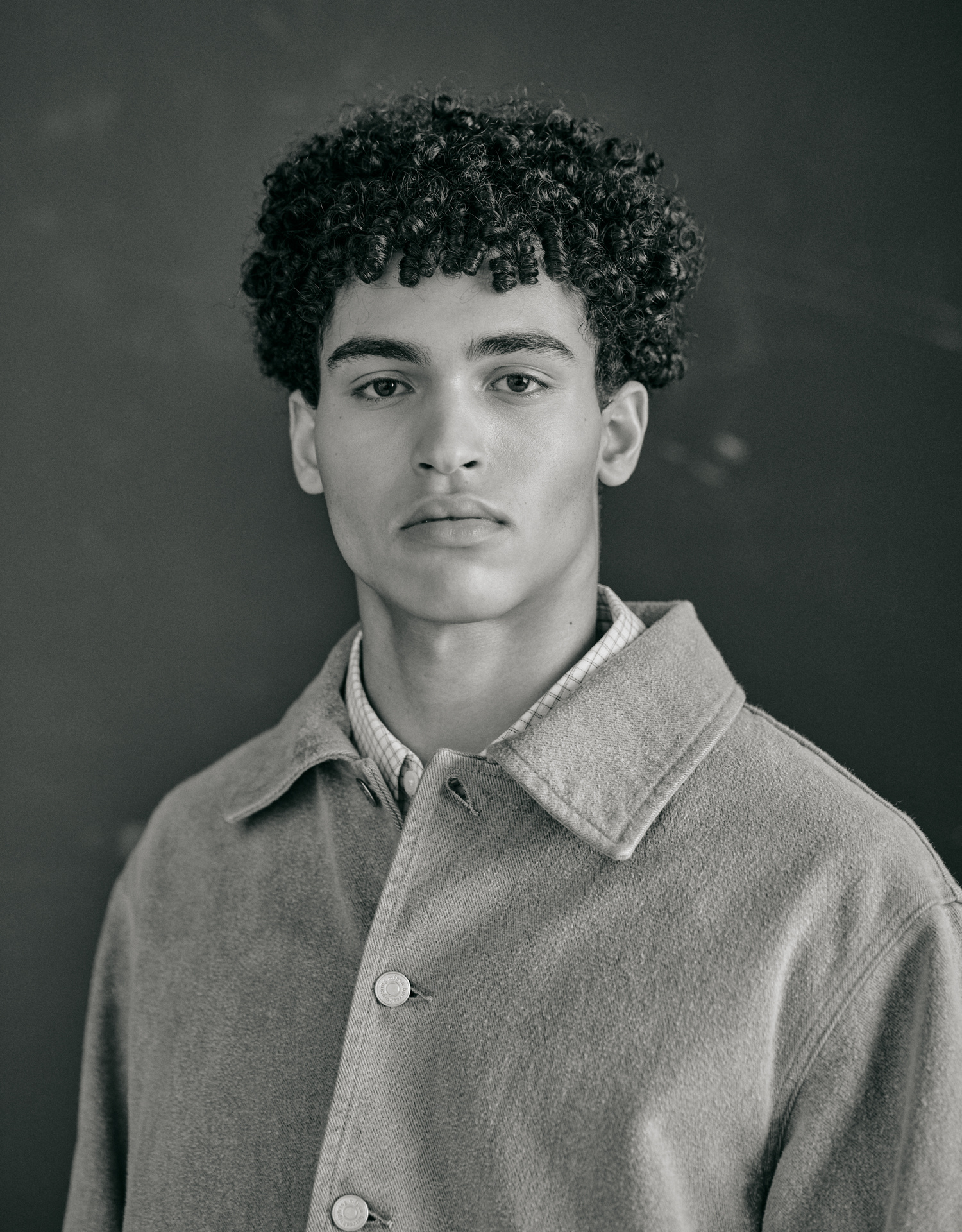

“This shirt is something your dad would wear,” Sigurd says. “We take these classic shirting materials and cut them in an oversized fit, which gives them a more countercultural edge. The fabric itself is very traditional, but we subvert it by changing the shape. The scarf is made from recycled wool.” Shirt, trousers, and scarf from MFPEN F/W ‘25

Chris Force: Tell me how things started. Did you have big plans for Mfpen? Did you imagine running a team?

Sigurd Bank: For the first five years it was just me. There was no plan back then, but at some point it started escalating. There were many moments where I’d sit down and think, “OK, now we have the perfect size. We’re not missing anyone.” It felt really good at those points, and I’ve had that feeling multiple times throughout our growth. I have it again now because the team feels perfect at this size.

But sometimes growth is just inevitable. Then I made this dumb decision to do womenswear two years ago. I don’t regret it, but I was thinking, “Why did I do that?” I think that’s what happens when everything feels a little bit—I wouldn’t say safe—but when you reach a point where everything is comfortable, then you do something disruptive. Same with footwear. We started making our first real footwear collection for this upcoming season. You can’t help it. I think that’s the issue: every time you add new products to your lineup, you need more people to handle the workload.

Especially when everyone’s so interested in what you’re doing. I’m sure it would be different if no one was paying attention. But when people are curious about your work, it’s a motivator to see what else you could present.

We want to push what we do and always get better. But we don’t have this urge of growing and being bigger. We always hear about these brands saying, “We want to be the next Ralph Lauren.” That’s not for me. The goal is not getting bigger. I think the reason we got to our current size is because we do some good stuff that people enjoy. It’s hard to put a brake on it.

You said for five years you worked by yourself. You’re an independent shop. Tell me about that era. What were things looking like?

I know the year I got my first real salary it was 2019, and I know that because that’s also when my daughter was born. A lot of things happened at once. Before that I also worked with consultants. Four months later COVID hit at the beginning of 2020, and that’s where the brand started to evolve in terms of growth. It had a lot to do with the e-commerce sales during COVID. But it also gave me more breathing room because I didn’t have to go to trade shows or showrooms in Paris. I could focus more on development.

During COVID I had one employee. When we came out the other side of COVID, suddenly we had four people on the team. That little COVID financial push we got made us grow. When you’re four people on the team, you easily become five. Everything had been very organic growth. I owned the company myself 100%.

“I don’t know if there are cool fashion scenes anymore. After the internet, especially social media, there’s no room to grow in the same way.” -Siguard Bank

Were you always interested in fashion?

My granddad was a tailor, but I would say I was actually interested in fashion. I don’t know if I really am now. Maybe to some extent, but “fashion” isn’t necessarily the best word. I’m more interested in product and craftsmanship. Of course Mfpen is a lot more than just product and craftsmanship—there’s also the photography and all these things that excite me. Making collections, getting it together, making the campaigns, and building the universe.

I don’t want to sound pretentious saying I’m not into fashion, because of course to some extent I am, but I don’t care much for what Demna does now for example. It’s not an interest of mine.

If I see a runway show, I’m often more interested in the music or other elements. I don’t care much about trends and fashion. It’s never been my thing. I think when clothing or style came to my attention it was when I was a teenager. I was into skateboarding, and that’s when you think about how you dress and how the world perceives you and how you want to be perceived. Subculture and all these things. That’s my earliest memory of fashion, but it has nothing to do with fashion.

I grew up on the East Coast hardcore and punk scenes, and it was very anti-fashion. Anything to do with big brands or big capitalism was implicitly not considered punk rock or underground. But, when I look back at it, it’s clear that world was so formative for fashion today.

I’m a hardcore kid too. I got to know my commercial manager for Mfpen, Hugo, because of post-hardcore. We were at the same showroom one day and someone was playing Glassjaw. We both recognized it and it evolved from there. Someone once asked me, “Why are there so many hardcore heads in fashion now?” I think it’s more about actual style. It’s not about fashion, it’s about caring about product to some extent.

How did having a daughter change your life and change your work?

It changed my life the way it does for everyone who has kids. But in terms of fashion, it didn’t change much. She did a print for the F/W ‘26 collection we’re working on now. She’s almost six, and her handwriting is insane. I ask her to write stuff and it doesn’t look like typical kid writing.

Are there other brands that you look at right now that you kind of think of as colleagues or peers?

Copenhagen has quite a lot of menswear brands. I wouldn’t say we help each other, but we have a community. We meet each other for a beer or we go to the fabric fairs together. I meet up with the Our Legacy guys every time I’m in Milan, and this Dutch brand called Camiel Fortgens. It’s nice that we’re not competing but trying to push each other forward instead.

This trench coat is made from 100% post-consumer recycled wool. “There’s this mill that

collects end-of-life wool garments and breaks them down into new fibers,” Sigurd says. “When they make the fabric, no additional dyeing is needed because they sort all the incoming wool sweaters by color before processing.” Shirt, coat, and trousers from MFPEN F/W ‘25

Outside of Copenhagen and Milan, are there other fashion scenes you think are doing interesting things right now?

I don’t know if there are cool fashion scenes anymore. After the internet, especially social media, there’s no room to grow in the same way. People dress the same way in Tokyo as in Copenhagen and New York, more or less. Everything feels very homogeneous. If someone’s wearing something and looks cool, the next day people have seen it on TikTok and they start dressing the same way.

You somewhat famously don’t do a ton of marketing, which is unique for how popular the brand has become. What do you attribute that to?

I’m kind of anti-commercial. I don’t mind people doing ads, but it’s not my thing. It gets a bit too capitalistic in a way, and I don’t want to force my brand into someone’s feed on their phone. I don’t think that anyone notices we don’t do it, but I think some people would notice if we started doing it.

The brand is going really well without it, so why should we start? My accountant said one day, “It’s amazing you can do this without a marketing budget. Imagine what you could do if you started.” But we don’t need to sell more and we don’t need to be bigger. I’m content with slow growth.

You’re making your designs largely from deadstock fabrics, trying to use up what’s not being used by the industry. But then when that’s gone, is that piece completely done? Or do you have pieces that you continue to make, but then you’ll resource them from new materials?

The company was founded on deadstock. I would work for companies, go to factory visits, and see all these fabric rolls. I’d ask, “What are you going to do with them?” and they’d say, “You can have them.” But now we’ve grown beyond that approach. We still buy deadstock—more than ever, actually—but our collection is so vast now that we need other fabrics alongside deadstock. We use a lot of recycled wool and linen, always trying to choose low-impact materials. We rarely use polyester, and when we do, it’s always recycled polyester—though I’m not even sure that’s great for the environment. We try to source the best possible fabrics within our reach and knowledge.

When we do use deadstock, if you look at our website, garments often sell out really fast. Sometimes we can only make 50 pieces, sometimes just 12, depending on how much fabric is available. We get a lot of complaints from people asking, “Why does everything always sell out?” but that’s just the fabric that was available to us. It’s actually kind of fun in a way.

Products used to last longer on the site, but since we sell more now, things move quickly. We show our main collection in Paris to all the buyers. Then when we put production orders in, we often add 10 or 12 more styles to the collection. Sometimes we can only make a couple hundred of a shirt that becomes popular, and we sell way more than that. Then we find alternative deadstock fabrics and go back to stores asking, “Hey do you want this alternative version instead?” So the collection keeps growing throughout the season.

If demand is high, most businesses would raise their prices. But it seems like you haven’t done that.

The prices have gone up the last couple of years with inflation. Factory prices go up and everything goes up. But I’ve always thought—maybe it’s because I’m not a fashion head—why would I make a product that my friends couldn’t afford? I don’t care if brands charge €800 for a T-shirt, but to me that’s a bit bullshit. I enjoy the fact that it’s not only rich people who can afford the clothing I make.

What’s the most expensive thing that you’ve bought in your closet?

I have an Mfpen coat that’s €900 or €1,000. But I didn’t pay that for it. I think that’s the most expensive item. I don’t buy expensive clothing.

Do you have any favorite band T-shirts or old vintage hardcore shirts?

I don’t think hardcore bands make the greatest T-shirts. I think metal T-shirts are better. One of my favorites is a Rival Schools T-shirt that’s quite cool. I also have a shirt from the band Sunn O))) that is very cool too. There’s a guy on it praying next to a skeleton. I try to buy as many as I can at concerts of course, but sometimes you have to find them vintage.

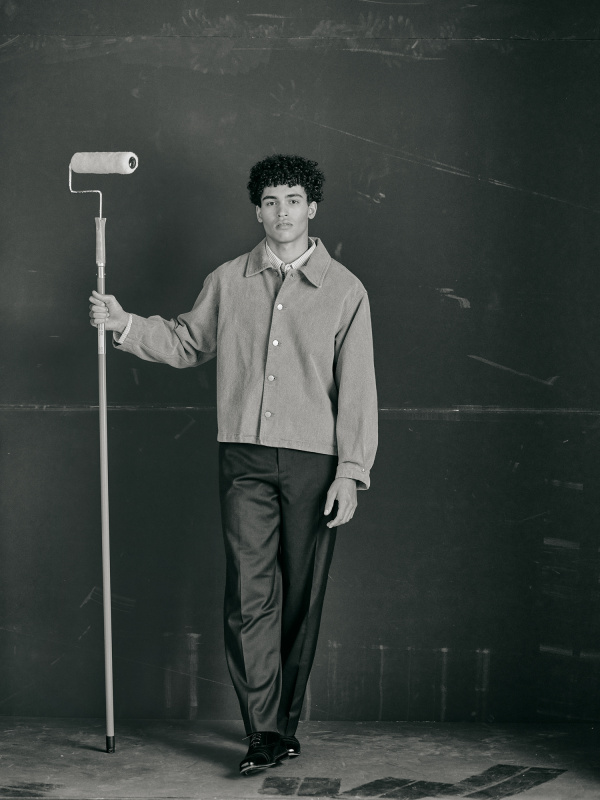

“I try to always maintain this countercultural aesthetic in our lookbooks and campaigns—I wouldn’t call it hardcore, but definitely countercultural.” Shirt and trousers from MFPEN F/W ‘25

What was the last show you went to?

This summer I saw Deftones. I especially love early Deftones. I was all the way up in the front, and that was fun—lots of moshing. There’s also a Danish band called EYES, which you should check out. There’s a lot of Danish hardcore out there at the moment.

There’s also a New York band called CANDY. It’s quite underground, but they’re very cool. I went to see them once and found out they love Mfpen. We’re trying to make an event happen in New York the next time they play.

Did you learn any tailoring from your grandfather?

I’m educated in production and sourcing, and we work closely with some very good factories. There’s always someone who’s smarter than you within development. We also work with a very good pattern maker. We have a factory that’s very skilled and they have all the pressing machines. When you do tailored pieces, you want to work with a factory that has the tools to make all the pressing on the shoulders, chest, and lapel. What I’m saying is it’s all about relationships with other people and skill set.

When you start your F/W collection for next year, are you building off of last year’s, or do you start from the beginning and come up with everything from scratch?

For us everything is a constant process. We have kickoff meetings of course, but we never sit down and say, “OK today we’re going to start thinking about this collection.” Sometimes we work on ideas for one collection but decide to hold them for the next one. It’s always this ongoing creative flow.

We always build on earlier collections because it would be too much work to create a completely new collection from scratch every season. The more you build on previous collections, the more you can focus your limited time and resources on developing truly new elements. For example our shirting often uses the same basic cut—we have different cuts, but then we choose new fabrics, new washes, new details. We build on the same foundational shirt pattern, and the same approach applies to our denim fits.

Where did you start with making this women’s collection, since you weren’t necessarily building off of anything previously?

The reason we started womenswear was because we had a lot of deadstock fabrics with quantities too small for men’s production. Sometimes we could only make 30 pairs of trousers from a fabric, which would sell out immediately. Our menswear now requires larger quantities to make economic sense. I thought, “This fabric would work well for women’s trousers.” We started using these smaller deadstock lots for women’s pieces, but that only lasted about a season before the women’s line outgrew that too.

Now we’re committed to womenswear, though we’ve always included women in our men’s lookbooks. I think it creates a good aesthetic to have women styled in the lookbooks.

For the women’s line we started by building from the men’s foundation, but we didn’t want it to just be a sized-down version of the men’s pieces. It needed to be its own thing while still being an extension of the men’s line, since menswear defines Mfpen’s core aesthetic. The challenge was translating that DNA into women’s garments that feel authentic to both the brand and to womenswear.

Very cool. How have you thought about doing that? Can you see doing more runway or working more shows, or is this almost launching a whole new line of the business?

Women’s feels like starting another company. For the buyers, we decided to take our own approach—fuck their traditional schedule. We run on our own calendar, and if they want to follow it, fine. Most women’s buyers attend both men’s and women’s shows anyway. But we also needed to maintain our factory infrastructure. When we buy a fabric and use it for both men’s and women’s pieces, everything has to be produced simultaneously since we share a lot of fabrics across both lines. So women’s just follows the men’s calendar, which works for now.

But there are all these other complications we didn’t anticipate. We need a bigger showroom in Paris now because the women’s collection takes up space. We need a bigger office because we now have a dedicated women’s team. There are always these logistical things you don’t think about.

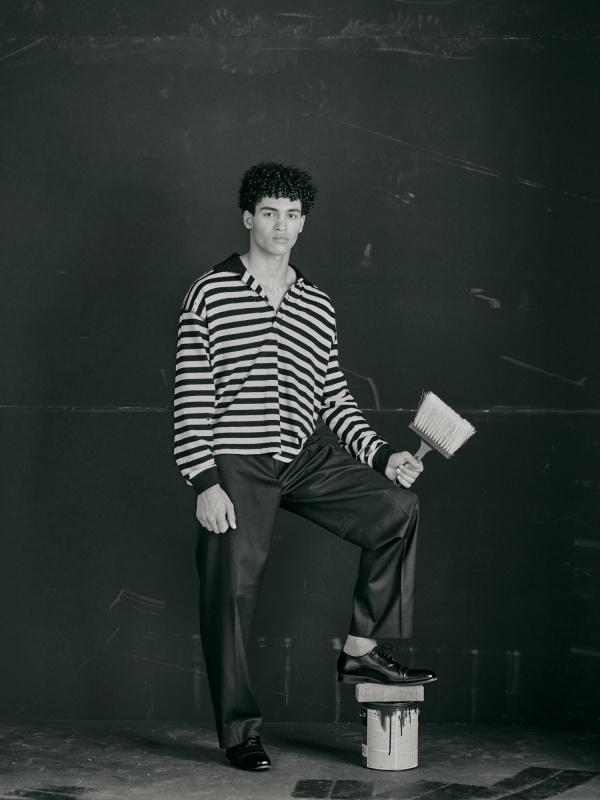

“This shirt was made from a deadstock fabric that we found,” says Sigurd. “When we developed the style, it felt a bit boring because it was just striped, so we added the holes. We thought it would be fun because a striped sweater is historically very sailor-look.” Shirt and trousers from MFPEN F/W ‘25

Are you going to have to move your Paris showroom?

We have a space in Paris in a gallery where we’ve had a great relationship with the owner for four years now every season. She’s basically a family friend. But we have to move to a new space because we’ve outgrown it.

All good problems to have. I think what you’ve done is just so incredible. I didn’t know that you were a hardcore punk rock kid too, but I think there is something kind of punk rock about your business, which is super cool.

Thank you. I try to always maintain this countercultural aesthetic in our lookbooks and campaigns—I wouldn’t call it hardcore, but definitely countercultural. Our S/S ‘26 collection, if you’ve seen those photos, was inspired by mall goth. Everyone our age went through that phase where you put black nail polish on your nails. I love that shock rock aesthetic—everyone listened to Marilyn Manson at some point. Everything was so aesthetically maximalist: black hair, chains, stockings, all these dramatic elements. I wanted to bring that energy into the collection.

I had this concept of kids who grew up but still carry that mall goth vibe into adulthood—maybe they’re at the office now, but you can still sense it. When you see our photos going forward, I want people to immediately recognize, “OK, this is them, this is their aesthetic.”

Model: Adrien Dubois, Ford Models. Grooming by Katrina Graham, The Rock Agency

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 15.