“A woman who doesn’t wear high heels is not a woman.”

A customer’s words cut through the smoky jazz bar where art student Mari Katayama performed as a singer to make ends meet. Most people might have dismissed the comment, but the future artist saw it as a creative challenge. Born with a rare congenital disorder and having chosen amputation at age nine, she knew conventional high heels weren’t made for her prosthetic legs.

So she made her own.

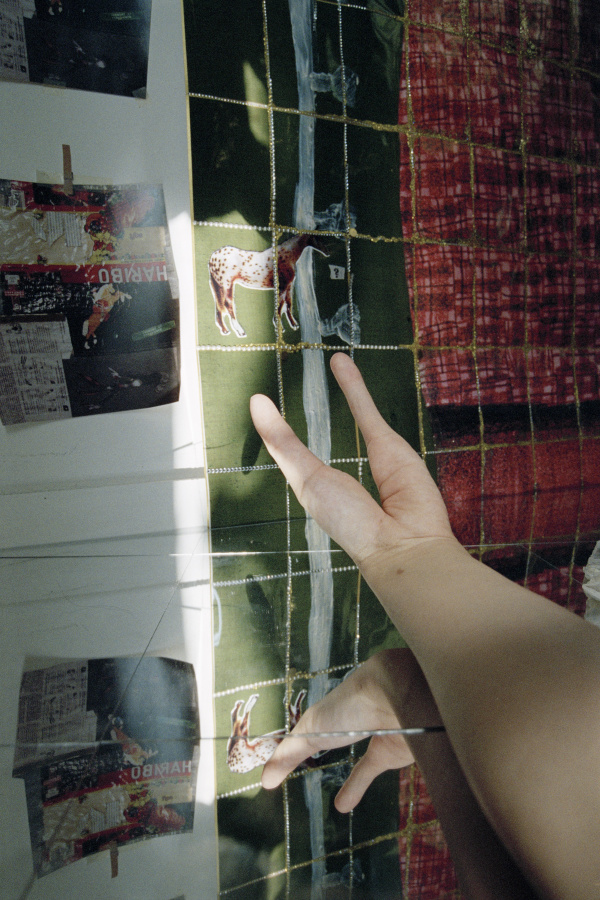

From her home studio in Japan’s Gunma Prefecture, artist Mari Katayama constructs entire worlds by hand. Each self-portrait begins with months of sewing, beading, and embroidering life-size dolls and elaborate textile pieces. Photo by Jorgen Axelvall

“I bought standard high heels, adapted them for my prosthetics, and performed while wearing them on stage,” Mari says. “It was a small personal project but also quite challenging.” That moment of defiance would eventually become her High Heel project, a series of self-portraits that transformed a practical solution into art. Each image asked the same question: “Why do we let others dictate what femininity looks like?”

This kind of creative problem-solving wasn’t new to Mari. Growing up in Japan’s industrial Gunma Prefecture, the constant clatter of sewing machines provided the soundtrack to her youth. Her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother worked as seamstresses in her home while her grandfather sketched and wrote poetry. Though money was scarce, Mari’s mother instilled the belief that anything could be “made.”

- Mari’s home in Gunma is itself a kind of artwork. Her husband’s DJ records shares space with Mari’s desk and art ma- terials, a domestic landscape that feels both lived-in and deliberately composed.

- Photos by Jorgan Axelvall

“‘If it doesn’t exist, create it.’ That was my mother’s mantra,” Mari says. Outside their window smokestacks and factory lines stretched across the landscape. They were proof to young Mari that people could build anything they set their minds to.

Growing up in Gunma also gave Mari what she calls an “ambivalent perspective.” She could appreciate things as they were, but often felt an urge to tear them apart and rebuild them. “That tension between acceptance and transformation became a source of inspiration in my artistic life,” she says.

Mari’s “garden,” the grounds surrounding her home and studio in Gunma Prefecture. Raised

in Gunma since childhood, the constant clatter of sewing machines provided the soundtrack to her youth. Her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother worked as seamstresses in her home while her grandfather sketched and wrote poetry. Photo by Jorgen Axelvall

For Mari, creation has always been a part of daily life. Teaching herself to sew as a child, she began by creating small textile objects decorated with beads. “Much of my early work didn’t match what I had envisioned,” she says. “Sometimes I wasn’t even sure what I had created. They were pieces without clear function or identity which initially frustrated me. In Japanese culture things need to serve a purpose.”

When MySpace and the Japanese social media site Mixi started to gain popularity, a teenage Mari began posting her poems, photos, and drawings online as a hobby. Her posts caught the attention of photographers who soon started hiring her as a model, often wanting to photograph her alongside the objects she created.

In the studio where she works today, tucked into her home in Gunma, hand-sewn body doubles are adorned with Swarovski crystals. Newspaper clippings, shells, and pearls line the walls and shelves. Fabric scraps, lace, and beads, are part of her domestic landscape. Photo by Jorgen Axelvall

“Even though I made the objects, the photos eventually became the photographer’s possessions,” she says. “That felt strange to me, so I began taking photographs myself. I would decorate my room with hand-sewn objects, paintings, collaged boxes, and look into the viewfinder many times to frame a picture.”

Mari eventually enrolled in the Department of Intermedia Art at Tokyo University of the Arts, singing at a jazz bar to help with tuition. There she met Hiroaki Watanabe, a Japanese DJ also known as PSYCHOGEM. “I had a crush on him for about ten years, and then we got married,” she says. “I originally organized techno parties and invited him to DJ. That’s how it started.”

This fall marked a major milestone for Mari with the release of Synthesis, her first artist book. Above: “Tree of Life #009,” 2025. Photo by Mari Katayama

After graduating with a master’s degree in 2012, Mari had no intention of pursuing art professionally. Yet as she searched for better-paying work, exhibition invitations began coming in, leading her to create several photo series and eventually present her first solo exhibition abroad in London.

“This was a turning point that launched my international career in 2019,” Mari says. “I presented a wide range of my work and Ralph Rugoff, who was the artistic director of the 58th Venice Biennale, came to the opening.” After seeing her newest pieces, he added them to the Venice lineup. “Thanks to that, I was able to show a comprehensive selection at Venice as well.”

“Tree of Life #011” commissioned by the V&A Parasol Foundation Women in Photography

project with support from the Parasol Foundation Trust. Photo by Mari Katayama, courtesy

of Mari Katayama Studio and Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve, Paris

The studio where she works today, tucked into her home in Gunma, is itself a kind of artwork: hand-sewn body doubles adorned with Swarovski crystals, newspaper clippings, shells, and pearls line the walls and shelves. Her husband’s DJ gear shares space with Mari’s fabric scraps, lace, and beads, a domestic landscape that feels both lived-in and deliberately composed.

“I still buy materials at DIY stores, supermarkets, discount shops, or reuse scraps from daily life,” she says. “The materials I use are very accessible. When I create my sewn objects, I print on transfer sheets for fabric using a regular home printer and sew everything together by hand, stitch by stitch.

“Bystander #014,” 2016 from Mari’s “On The Way Home” series. Photo by Mari Katayama

“After my photos began to circulate as ‘artwork,’ I became even more intentional about the materials I used. When you try to step from the reach of your own hands into the wider world, it’s easy to lose sight of what you can protect, and what truly matters.”

Mari’s current practice has evolved into a multifaceted approach. Sculpture, sewing, photography, and performance work in concert, with each discipline folding into the other. She builds elaborate sets around herself, constructing entire worlds filled with life-size dolls and objects she’s spent hours embroidering by hand.

“Tree of Life #026,” 2025. Photo by Mari Katayama, courtesy of Mari Katayama Studio and Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve, Paris

Once these ethereal objects are made, she installs them and places herself into the frame, using her own body as a mannequin to best convey the mood of her work. In her “Bystander” series, for example, she appears on a beach wearing tentacled prostheses. Her body and the sewn figure blend together visually, making it hard to tell where Mari ends and the textile object begins.

For Mari, the camera becomes a kind of equalizer. It blurs the lines others have drawn around her. Through the lens her body isn’t a subject of pity or curiosity; it’s simply present, integrated into the composition, and essential to the artwork’s meaning.

- When she settled into her new atelier, Mari visited the nearest Shinto shrine, a nod to the Japanese custom of greeting the local spiritual site at the start of something new.

- Rice fields surrounding Mari’s village, captured from the train just before Kunisada Station in Gunma Prefecture. Photos by Jorgen Axelvall

“Every time I hold a heavy camera I become aware of my body and its limitations,” she says. “Even if I am thankful for my body, it’s impossible for me to love my whole body. But oddly, once my body is in photography, negative feelings and the hardships of shooting become a thing of the past in an instant.

“I believe that everyone has something unique about their body. A fresh vegetable is already beautiful and delicious on its own, just as nature makes it. In Japan individuality is often hidden for fear of standing out, but my role as an artist is to prepare, present, and transform to highlight qualities that might not be noticed otherwise.”

Mari’s studio. “I still buy materials at DIY stores, supermarkets, discount shops, or reuse scraps from daily life,” she says. Photo by Jorgan Axelvall

Three years ago, Mari says her creative possibilities exploded when she received her first electronic prosthetic leg, which uses sensors and microprocessors to adjust in real-time to the user’s gait and environment. Suddenly outdoor photography became possible. Projects she couldn’t even imagine previously were now within reach.

“The new leg changed my whole life,” she says. “I stopped tripping and posing during shoots became much easier. I also walk more while taking in the scenery and chatting with family and friends, which built up my stamina; now I’m even looking to try track and field.”

“Tree of Life #017,” 2025. Commissioned by the V&A Parasol Foundation Women in Photography project with support from the Parasol Foundation Trust. Photo by Mari Katayama, courtesy of Mari Katayama Studio and Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve, Paris

As we sift through photos of her in her hometown, I can’t help but comment on how chic she looks. She laughs. In one shot she’s perched on playground equipment at Kunisada Park where she often takes her eight-year-old daughter, wearing black fishnets and a graphic tee, her prosthetics decorated with self-drawn tattoos, something she’s been doing since her early years.

“I contemplate at Kunisada Park, partly because of the simple presence of greenery,” she says. “It’s not necessarily a deeply ‘inspirational’ place for my art. It’s more like an extension of my daily life, similar to how someone might view the garden in their own backyard.”

Commissioned by the V&A Parasol Foundation Women in Photography project with support from the Parasol Foundation Trust. Photo by Mari Katayama, courtesy of Mari Katayama Studio and Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve, Paris

Despite living a relatively quiet, grounded life with her family in Gunma, Mari’s work has found an extraordinary international reach. In 2021 Tate Modern acquired a wide range of her work, a validation that placed her practice alongside some of the world’s most significant contemporary artists. Her pieces have been on display there since 2022 and remain on view today. Earlier this year she unveiled a commission for the V&A’s Parasol Foundation.

Yet the reception to her work varies depending on where it’s shown. “When I present work overseas, the attention is directed primarily to the art itself,” Mari says. “I am seen and engaged with simply as an artist, and people focus on the form and meaning of my work. Back home people are more curious about me personally. In Japan there isn’t as strong a culture of discussing art in depth. The interest goes beyond the artwork into who I am privately.”

“With this new work I hope to spread art in a way that feels familiar and accessible so that everyone can feel close to it,” Mari says. “The question I’m always exploring is, ‘How do we

coexist even when our philosophies are different?’” Above: “In Her Room #001,” 2025. Photo by Mari Katayama, courtesy of Mari Katayama Studio and Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve, Paris

This fall marks another major milestone for Mari with the release of Synthesis, her first artist’s book. The 200-page volume captures six years of her life from 2019 to 2025, the period when she became a mother and moved from Tokyo back to her childhood home in Gunma. The book compiles nine of her photo collections, including her latest work titled “Tree of Life,” all produced in her home studio. In the series, dozens of sewn figures appear in different stages of being finished. Some are fully decorated, others are just starting out.

“With this new work I hope to spread art in a way that feels familiar and accessible so that everyone can feel close to it,” she says. “The question I’m always exploring is, ‘How do we coexist even when our philosophies are different?’”

“‘Tree of Life’ reflects that—it’s very much a work in progress, an expression of the fact that I haven’t found a perfect answer yet. I’m still in the middle of that search.”

Mari Katayama for Sixtysix Issue 15.

Interview translation by Manami Umeda

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 15.