Marcel Wanders is often surrounded by incredible work. His own iconic product designs, his colleagues’ projects, new designers’ work, it never ends. He opened his studio in 1996 and completed his now famous Knotted Chair before moving to Amsterdam in 2001—the same year he founded Moooi with Casper Vissers. And yet he rarely comes across anything that makes him stop and think, “Wow.” The work of artist and designer Audrey Large did just that. “She has found a way to use her new design tools in a very different way than we all use our old design tools and in doing so she has developed a style and visual language that is innovative and different.”

Marcel himself has a long history of innovation. He won the Wired technology award in 2002 with the first 3D-printed product—the incredible and lighthearted Airborne Snotty Vase, which he built after scanning a sneeze in mid-air. He’s designed wireless energy-making lamps for Moooi using his patented sandwich technology, and he created a microwave with a TV in the door for Holland Electro. “I created a ceramic pencil sharpener, a chair out of rope, the lightest and most stackable plastic cup in bio-based materials, and so many other things,” he says. “I am magician and secretly an engineer.”

We recently joined a conversation with Marcel from his home in Mallorca alongside contemporary designer Audrey from her home just outside of Rotterdam to talk about the evolving intersection of art, design, and technology. Audrey is quickly becoming known for her work creating enormous otherworldly 3D-printed objects that test the limits of digital fabrication. —Laura Rote

- “I work more on challenging the perception of what’s real. I do this through objects,” Audrey says.

- “For me it’s more about perception and materiality and how we perceive what is real. I contradict the sense of knowing what you’re looking at.”

Marcel Wanders: It’s hardly ever that I’m really impressed. And if I’m impressed and surprised at the same time, that never happens. So when I first saw your work, Audrey, in Milan, I was really shocked. It was such a different type of design, with so many questions as to how to interpret this. I thought, “I have so much respect for the person who was able to make this. I would love to speak to her one day.” So thank you for being here.

Audrey Large: Thank you for your words. That is very nice to hear. I’m happy you saw the work in real life because it’s different than in pictures.

Marcel: For me, if you’re a designer you look around the world and you’re re-engineering everything you see. It’s like the whole day you’re examining the world by how things are made, why they are the way they are, and so I was really shocked to see something I didn’t know how to deal with. It’s really special. In art that happens more often, but in design it hardly ever happens. It’s something I would love to know from you: If we talk about your work, would you like it to be discussed in the context of art or in the context of design or in the context of technology? How do you want us and the world to look at it?

Audrey: I studied design, and I am mostly in the design field, but I don’t have a problem-solving approach. I don’t try to bring function.

Marcel: One of the things designers do and I think artists also do is they question themselves and the relevance of the work. In design one of the answers could be that it’s relevant because it’s useful; it’s helping people live their lives. In art it can be that your message is relevant for culture; it’s relevant for getting a message out because it’s political or it’s social or it’s ecological or whatever. What is the relevance of your work?

Audrey: I work more on challenging the perception of what’s real. I do this through objects. For me it’s more about perception and materiality and how we perceive what is real. I contradict the sense of knowing what you’re looking at.

Marcel: The work you do I think is very connected to the digital world, to the metaverse. Your aesthetic I would say is fit for the metaverse, and it’s probably also drawn from the metaverse. What is surprising is that you are putting the reality of the metaverse into the reality we live in. It’s not like I’m putting a Porsche in the metaverse; you’re putting crazy art that is made for the metaverse into reality.

“In the digital space there’s no constraint. It’s tempting for me to go as far as I can with the shape. Even the material I work with is this malleable skin that is forever changing, so it’s hard for me to stop. The further I go the more impossible the object.”

Audrey: I think because I have this object design background I’ve always been pushed to think about materialities. The thing is, I don’t know if I believe in the metaverse. I mean, it’s happening, but I feel we are trying to design in two separate realities. Maybe in the metaverse we present some escape from our ecological disaster—a shinier reality. When I use digital it’s more as a tool to help me embrace the material one. There’s a lot to learn philosophically from the digital realm—the way we look at things and envision material.

Marcel: So you’re not interested in the metaverse so much?

Audrey: I’m interested in building a metaverse that is not simulating the real—not to be lived in instead of the reality, something that will be more blended into the material world. I feel like we are designing the digital to replace the real by always going into simulations that are even more materialistic.

Marcel: I think we are waiting for the quality augmentation of the metaverse. That’s where the metaverse will blend with the real world. The moment Google Glass finally works after 10 years of having the first ones, then I think we will have the two worlds intertwine, which I think is interesting.

Audrey: The material world should also follow.

Marcel: Absolutely. For a few years and especially last year we really started to put the two worlds together. We’re like, “Let’s build a digital world that’s fucking amazing, but let’s not forget for the next few years we still have a body,” right? We still have to deal with our six senses and the real world so let’s get the tactile qualities and acoustic qualities and everything to a new level, which I think with digital we can do. The material world can be more interesting; your work is proof of that.

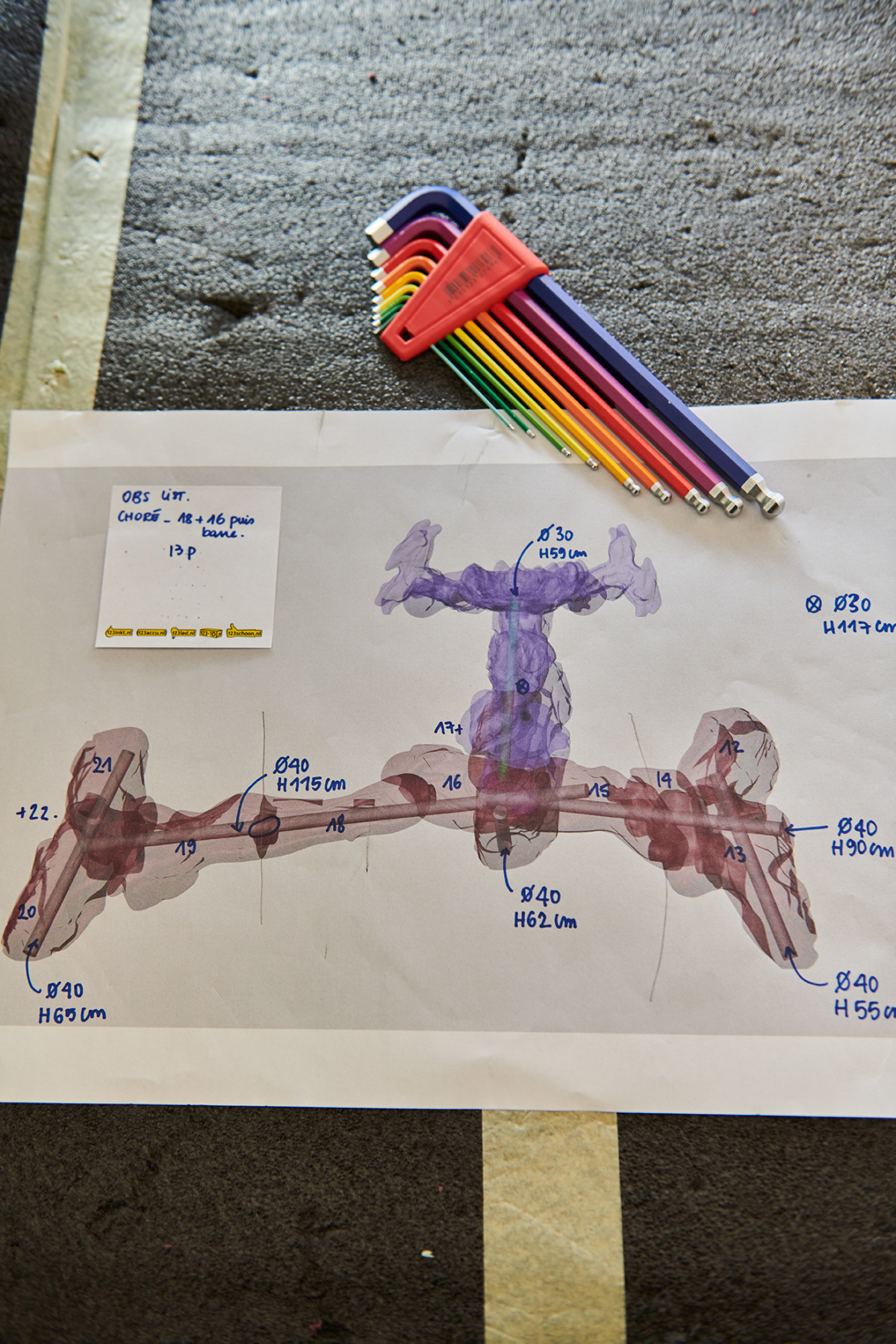

- Part of Audrey’s workspace

- Work in progress

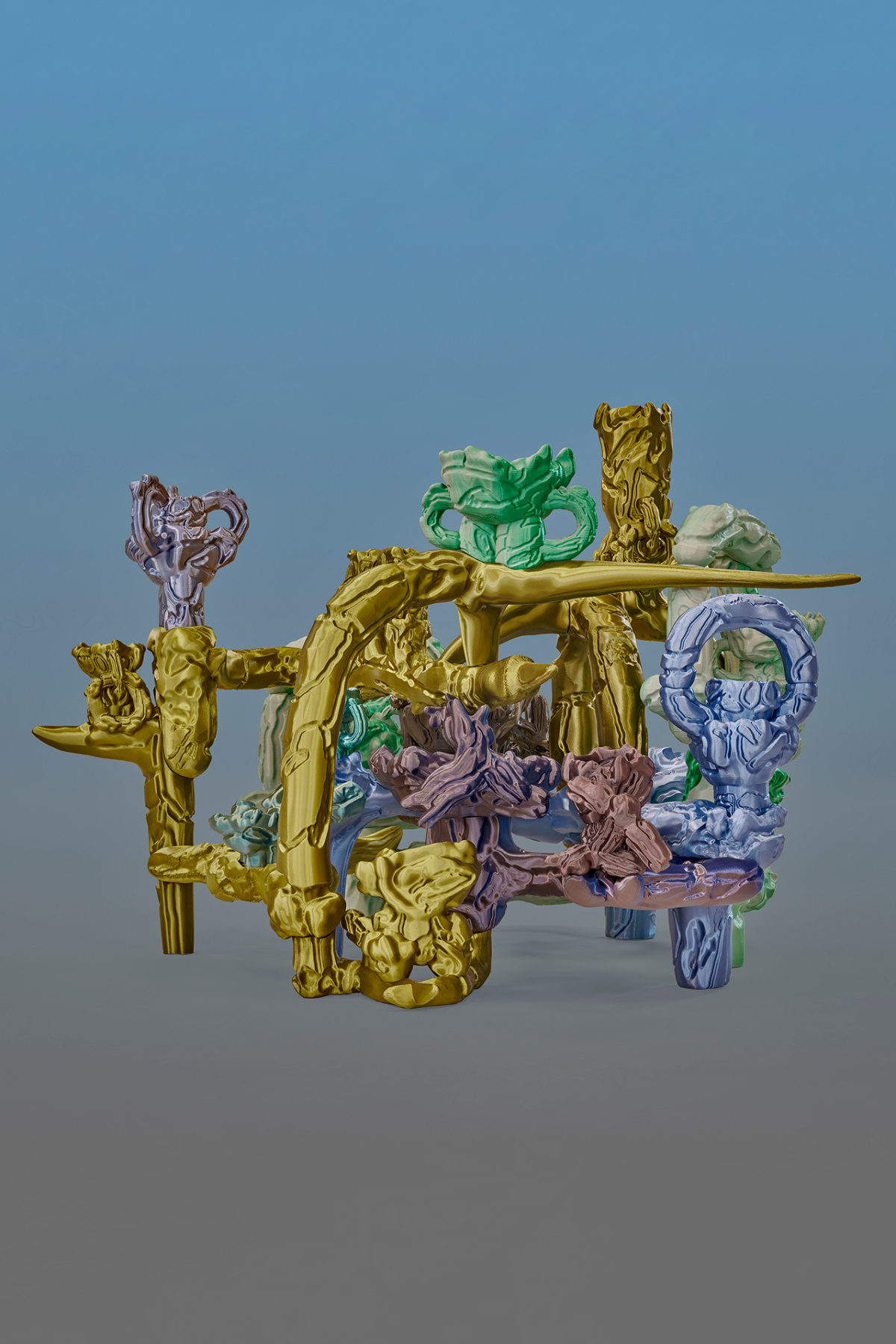

- “Scale to Infinity” 2021

Audrey: It should be one world. It shouldn’t be two. For me it will be all about being in the middle. This kind of online anxiety, this feeling of being stuck, being everywhere at once. There’s a spiritual gap.

Marcel: The metaverse is that, and the metaverse is also setting up a call through WhatsApp with friends in China. It’s all metaverse. It’s not only like put your goggles on and you’re in the metaverse. The metaverse is a bigger concept. We’re waiting for augmented reality to kick in because then it’s going to be really funny. Until then it’s not so great.

But I think it’s interesting that your work is influenced by the tools you have. The tools designers have—whether it’s a pencil or the first 2D technical drawings—they’ve always given real direction, and you’ve really found a new level to what computing power can do for designers. It’s really cool.

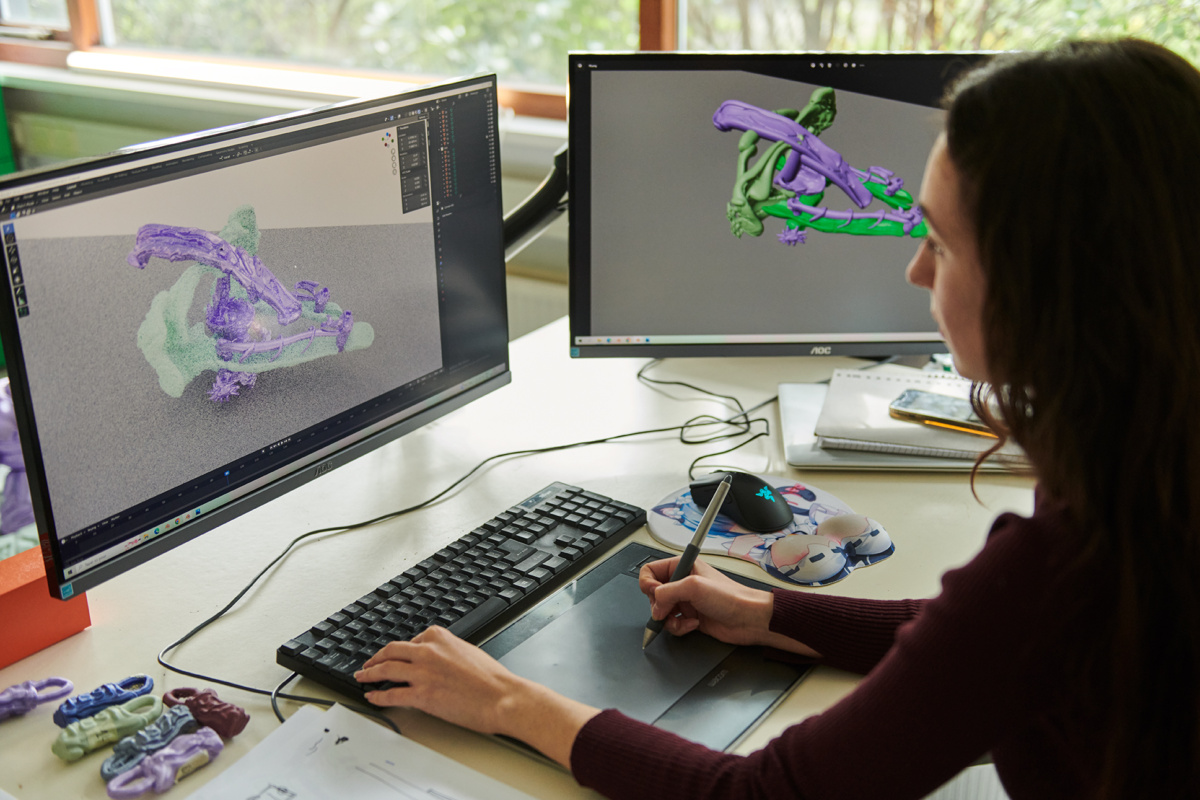

Audrey: I think there are two steps. The tools exist, and they are not new. If you look at what they are doing in cinema or CGI or game development, it’s very advanced. I’m not doing any crazy 3D modeling, you know? I learned everything on YouTube. It’s knowledge that is accessible, that is online, and there is a big community.

The second step was to bridge it with digital manufacturing. When I started 3D printing, which is also not a new technique, but let’s say we’re using the computer not as a space for simulation but more as a space for new representational freedom. I could go very far with the shape and use the full potential of it. 3D printing enabled me to bring this size and shape from the computer into the material world. It’s true that the shapes are very complex; it’s like a meeting point between what digital worlds allow me to do and finding the right way of translating this size into the material world.

Marcel: Do you expect your work will be more liked by designers who are more minimalist or designers who really create shapes and use culture and decoration?

Audrey: I never think about that.

Marcel: I understand, and you don’t have to, but it’s interesting.

Audrey: For me it’s more like, in the digital space there’s no constraint. It’s tempting for me to go as far as I can with the shape. Even the material I work with is this malleable skin that is forever changing, so it’s hard for me to stop. The further I go the more impossible the object.

What I make, sometimes children like it, or people interested in semiology like it. The works are very Baroque, but they are also futuristic, so they really stand in the middle, and I think that’s their strengths.

Marcel: I think that’s why they’re interesting; they’re Baroque, but they’re also minimalistic in a way.

Laura Rote: Marcel, speaking of thinking about how work is perceived, I know you’ve said if you’re not making mistakes, you’re not trying hard enough. What are some mistakes you’ve made?

Marcel: I’ve made mistakes so many times. Sometimes you can realize you made mistakes, but you don’t have to follow up on them. I mean, every drawing is a mistake until I finally do a good one, right? A saying like this is interesting because it gives you freedom to take risks, to say, “Fuck it. I’m going to do it anyhow.” You have to do the work you want to do. Being safe is risky.

There are so many things I could have done better. It doesn’t mean they’re failed projects; there are very few projects I think I shouldn’t have done, maybe five or so. For the rest you think in hindsight, “Oh my God, why did I do it this way?” But it’s not that it’s wrong. It’s like, “I’m going to do this thing even if it’s wrong.” It’s to give yourself the energy to come up with things you know you’re scared of. If you’re not scared of it, maybe it’s not even worth it.

Audrey: When I graduated I worked with 3D printing, but not with a company because it was too expensive. I used this online platform—working with people who had their own machines and offered the service. Then I bought my first machine and started to experiment with it or use it wrong. It’s how I had to start, I think, to do wrong sizes that no company would want to print because it was too risky or take too long. Now I have like 24 machines. It’s a lot. But again, it’s a DIY community. It’s knowledge that is online. I don’t have industrial machines or anything crazy. In that way it’s close to a sculptural approach.

I graduated from the Design Academy in the Netherlands in 2017, and I felt like I could just kind of exist—like this practice would be well received in between art and design—while I felt that if I went back to France, I didn’t have very much of a network.

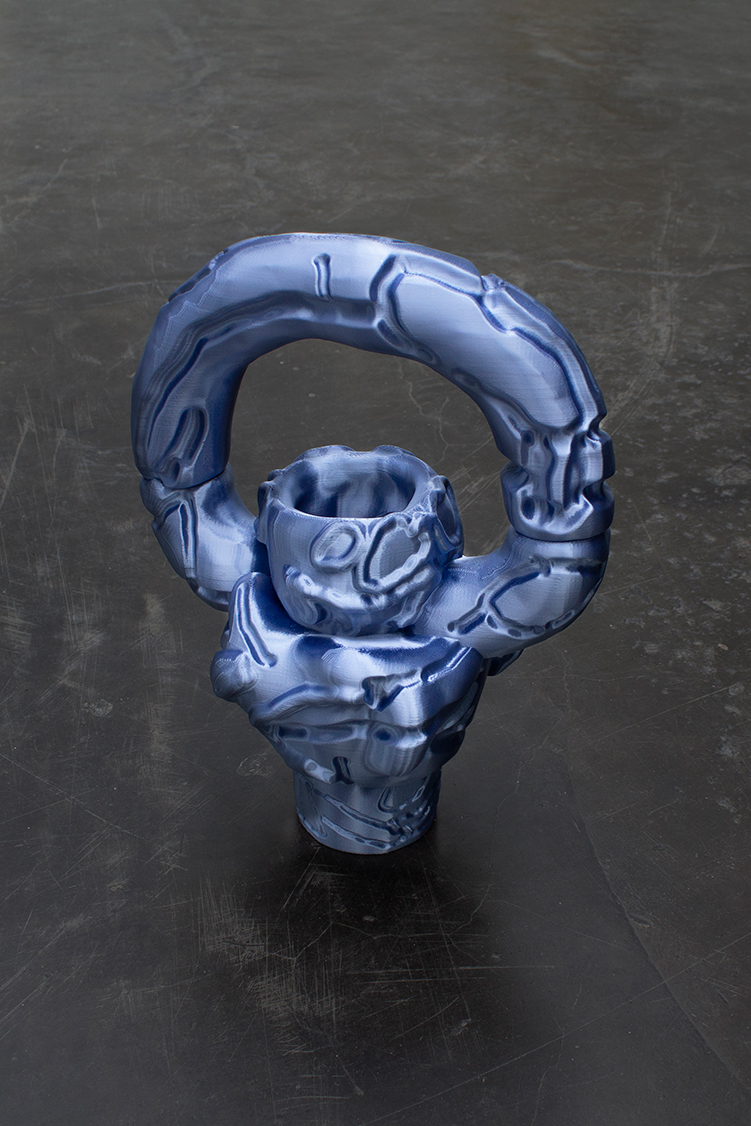

- “Meta Bowl” 2021

- Work in progress

- “Some Vibrant Things” 2020

Marcel: The good thing about the Netherlands is there is a good ecosystem for creativity. Life is a bit simple in the Netherlands. You can also survive with a bike and a little crappy house and that’s it. In a lot of cultures that’s not so easy. It’s a nice country to work in. It’s very well organized, and the services you need are there.

Audrey: After school I took a studio with my friends who graduated at the same time, and we started to make exhibitions and there’s a whole grant support structure. Then I entered this artist’s residency, again in between design and art. There were many moments that pushed me and gave me an opportunity to go further and work independently.

Marcel: It’s surprising how much has changed. That’s also because I’m very old (laughs). Look at old magazines, right? It’s unbelievable. When I started working, let’s say 1988, I finished school. Magazines were so boring. They were very local, and there were no real international magazines. That only started in the ’90s. And then design itself was very objective. There is no personal story; everybody had the same philosophy, except for a few crazy people from Italy and they were frowned upon by the whole design community. It was a barren place. Very little interesting happened. Magazines were the big thing in the ’90s so communication started to be different and therefore the stories of design could be communicated, and largely things became more personal and subjective.

Then there was the internet, and the whole thing started to become really international. Suddenly it made sense to go back to the old idea of having a workshop to make a cabinet and try to sell it to neighbors, but now your neighbors could be in Taipei. Behind that was a very new world of design responsibilities. I think now the two biggest influences are the growing of technology in different ways and the need for an ecological conversation. But visually it’s a different world out there. That’s good. It’d be awful and boring if it wasn’t that way.

As for what design looks like in the future, Audrey? You’re young.

“This kind of online anxiety, this feeling of being stuck, being everywhere at once. There’s a spiritual gap,” Audrey says.

Audrey: It’s a complicated question. Sometimes people ask me this because my work looks futuristic, but as I said before I’m using technologies that exist already. I’m really thinking about the now. I don’t mean that there are no consequences for the future, but I cannot make predictions. The future is made by the people.

Marcel: But there are things that are needed because design, maybe more than art, has a clear function and has to make our lives meaningful and also durable in a way. There is a responsibility in design that we have to address more seriously than we have done in the past.

Audrey: Definitely, especially in terms of sustainability and ecology. In terms of function, I mean, we know how to sit, right? The very fact of creating new things is problematic because we don’t need another chair. At the same time, creating for me is very fulfilling on a personal level. There will always be creation, but the thing is, when you asked me about how my work can be relevant, I cannot be relevant if I propose function just by itself because I feel like we don’t need more function; we have solved the problem of function, but maybe we need to displace our way of looking at how we are material.

Marcel: Function is organized, and to create a chair and say it’s amazing because you can sit on it, yes, that’s ridiculous. There are reasons why tomorrow a chair has to be different. It could be in how it is realized. Like the last vase I made was for an exhibition to make vases, and so I just made an artificial flower. I think about things like flowers in vases—they’re over. We should stop with that. These are stupid things we’ve done for years. The new vase has a very new functionality. That’s our work also. If you make a vase, punch a few holes in it, please (laughs).

- “Scale to Infinity” 2021

- “TP‐TS‐1121” 2018, for Nilufar Gallery in Milan

Audrey: In the same way it would be stupid to have vases and flowers in the metaverse. Why is this what we are doing with the digital world? We are trying to just make this version of what we already have.

Marcel: I think we will do flowers in the metaverse, but they will be silly. If they’re not amazing they should be more amazing. I don’t think they should be like our flowers. We can move this concept of flower or any other concept. If we lose the metaphors, if we lose the archetypes, then I think we’re lost.

Audrey: I think there are also new archetypes to be found. Sometimes I feel lost in the simulation, so when I try to use the computer I don’t try to simulate; I try to design little worlds. Each object becomes a little world in itself.

Marcel: How does a new archetype come about? Let’s say the laptop is a new archetype, right? A clamshell. It’s things that function differently, and people have no idea what they are until they start to get it.

Audrey: It needs to enter common knowledge. Like something everyone can agree on at some point.

Marcel: In a way a style is an archetype, right? Let’s say your work is considered an archetype—not of shape or function but an archetype of a digital style. I could make a work that people think is your work or the other way around; it has archetypal qualities I can repeat. Your work is so strong visually itself. This is something that is a recognizable quality that you could call its own archetype that can be multiplied.

Tomorrow someone can make a really beautiful Porsche Cayenne, but the surface is different, and the colors are different, and it’s your archetype. It will not be your work, and it will also not be a copy, but there’s an archetypical quality in the work. That’s the type of archetype we may find in the metaverse.

- Part of “Some Vibrant Things,” 2020, on exhibit as part of Milan Design Week.

Audrey: Ah, yes, so it’s not my archetype. It’s more like a digital look, digital aesthetic.

Marcel: Just claim it. You could now do it. Claim it.

Audrey: You think so?

Marcel: Yes, because it’s not only this; it’s also symmetrical, and there’s a few interesting things about your work that are recognizable, I believe.

Audrey: I like when it’s symmetrical but not. There’s always structure in the mass, that’s true.

Marcel: So we were saying maybe there will be archetypes in the digital world, even without being very functional. And if there are non-functional archetypes, what are they? What is the recognizable part of it if it’s not functional? Maybe structure?

Laura: How does life inform your art, Marcel? I know you’ve had some experiences, a serious car accident in 2022, for example, that may have changed your perspective or how you want to spend your time. Can you speak about that?

Marcel: People think, “Oh, you must look very differently at life now.” Not really. I know we’re fragile beings, and we have to seize the moment. I’ve looked at death in the eyes before—multiple times—so I’m not surprised by it again. It didn’t really change me. I mean, life is of course informing our work; it’s informing who we are, but life is also so big I don’t know where to start.

I’ve had four important loves in my life. Over time, always, if I wasn’t able to impress my girlfriend or to make them proud, I was not so excited about doing it anymore. I think a big part of the moves that I did were to impress my girlfriend (laughs).

Audrey: For me it’s blended. Especially in this type of work, where I try to push my own visual language. Of course I’m influenced by a lot of things, and I guess I put them inside of the work. The way I create and my lifestyle are very much intertwined. It takes up all of my hours, at least right now. I put all of myself in my work. But I haven’t experienced any major shift or opening eye moment; for me it feels very much like a continuum.

Marcel: They are super intertwined—just like the idea that if you wouldn’t have come to the Netherlands, your work would have been different. And now when you make this work, you can’t even leave the Netherlands anymore. It’s so connected. If you’re a designer and you make your work, you live your work.

Audrey: There are practical things, moments where you can earn money and continue your own practice. This is a privilege that allows you to take one path. Or sometimes you meet someone who will give you an opportunity and then your practice goes in another direction.

Marcel: Yes, it would be hard to suggest that life has no influence on life.

It’s really nice to see that you are a genuine designer, Audrey, and you make such amazing work. I am just super happy and proud of a whole new generation of designers, but definitely I’m proud of you. I hope you do great work in the future. I hope to see more of your work in the future and to stay proud of you. Thank you for this interview.

Audrey: Thank you. Maybe we can meet each other in Amsterdam. I mean, it’s not so far.

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 10 with the headline “Marcel Wanders in Conversation with Audrey Large.” Subscribe today.