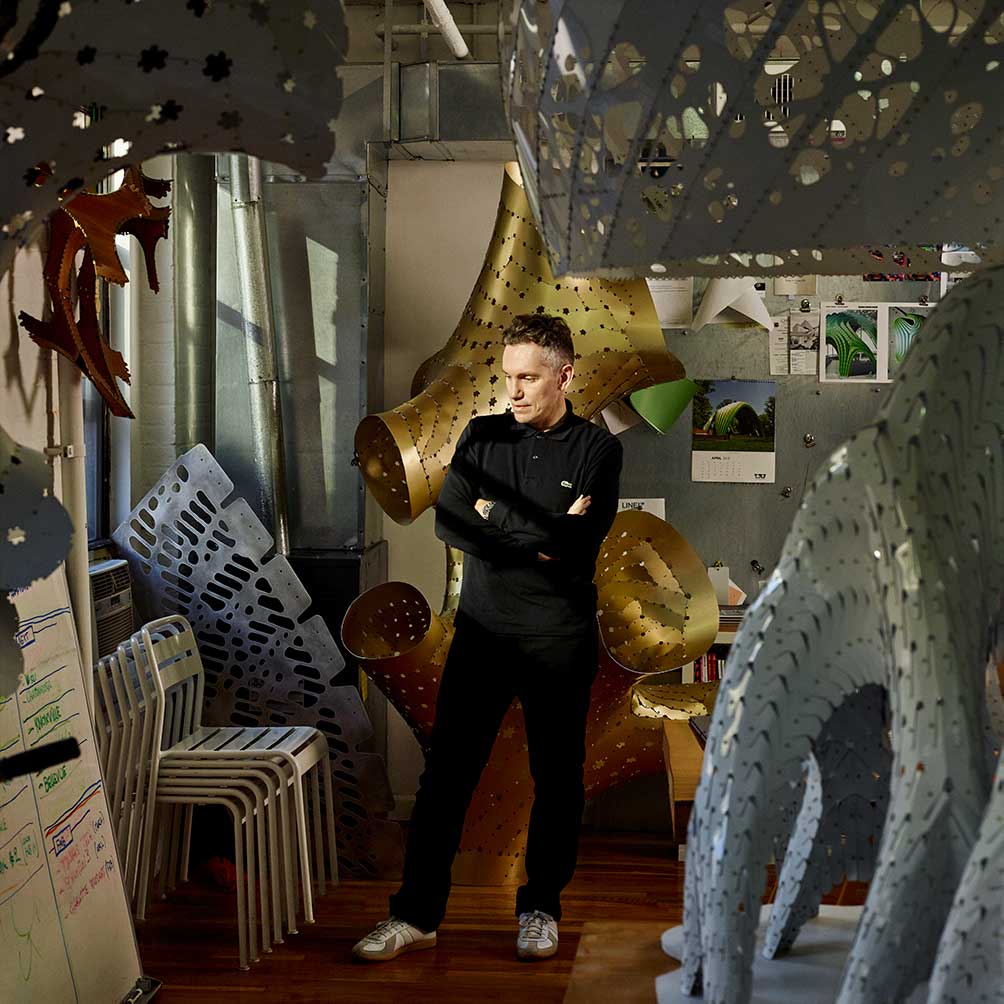

In the back corner of a large building in Dumbo, bars and shops at the base and a maze of offices and studios throughout, I find my way to an assembly of colorful, thin, planar elements: creatures, structures, surfaces. This is the space of Marc Fornes, architect and leader of THEVERYMANY, a New York-based studio specializing in large-scale, site-specific structures that unify skin, support, form, and experience into a single system. His otherworldly pavilions and public art installations transform spaces all over the world. Marc arrives a few minutes late, but it’s understandable. It snowed the night before—one of the few times this year—so much of the city is at a standstill. He didn’t anticipate not being able to zip over on his new scooter. We take off our dripping coats and Marc turns on all the lights, the heater, and offers water or tea.

The bright structures all over the studio, from tiny models (his “little monsters”) to hulking human-shaped forms, come alive. Everything in the space calls to be engaged with; you want to touch the scaly patterns and try to lift up spare parts. We settle into wide, angular pink chairs with a variety of green square pillows. It’s clear color is an important part of the team’s work as I scan the wall of projects in hot pink, chartreuse, and cool blue. I compliment the chairs, but Marc says there’s a flaw in the design. “No one who is visiting wants to fully sit back in the depth of the chair. They all sit at of the edge of the chair and probably feel a little precarious.” I notice I’m sitting at the end of the chair. Marc, in his black Doc Martens, black Levis, and turmeric yellow sweater, is both polished and casual. It’s clear from the accent that he’s French, but it could be the effortless chicness, too. We dive right into the life and work of Marc and his team, who were up very late last night getting a deadline finished.

- A wooden work from the early Aperiodic Tiling projects serves as a departure point that informs current work, which is more about achieving structural performance through a minimum of material. ‘Below that is perhaps our most important object in the studio—the foosball table! The first year we had a bit of extra money, we were choosing between buying that and a desktop 3D printer. The foosball table was clearly the better decision.’ Photo by Noah Kalina.

- This part cabinet of curiosities, part trophy case (right) showcases prototypes dating back to early 2000 as well as representations of large-scale projects and, to the right, early prototypes based on the Modoids project series (2009-2010). Photo by Noah Kalina.

So yesterday everybody was here; usually there is a lot more activity. Today everybody is dead.

Did you finish it?

Yes, we finished it yesterday. Fingers crossed it works. It’s for a large facade. It was an intense moment.

Do you start each day the same way when you come in?

There are two days, in a way, that are radically different. There’s the one I prefer and the one, well, you know when you do too much of one and you miss the other one? There’s the flying away [literally leaving the studio to travel for work] and the staying in the studio. There’s a lot of travel because we have projects all over.

My favorite is the day I am here in the studio, when I am getting stuff done. But flying is also so interesting because you arrive very early to the airport—too early—and suddenly you have the time of the flight to prepare a presentation for something you might’ve been working on for weeks and it might be for someone who has a very different interest from you. So you have to transform a body of work, which is very technical, what we do, very research-based, to something that might have a narrative. And you only have the length of the flight.

Most of your projects are all over the world?

Mostly everywhere in the U.S. and Canada. And now we’ve started to make work in Taipei, Shanghai, around Asia. We have some in Europe, because you know, I’m French. We would love to have some permanent work here, in New York, though we have done some temporary installations.

How long have you been in New York?

Based on the accent, what would you think?

Hard to say. Not too long?

Twelve years. It was around 2006. I guess that’s 13 years now.

How big is the team, and what are their roles like? Are they all building things in different capacities?

We are 10 people. We are all architects by training, in one way or another. The person who does the communication is an architect and even the person on the coding side, because we do a lot of coding, is an architect. We are all architects by training, but we practice on a very fine line between art and architecture. It’s a strange existence, in a way, because for the architect, they see us as the artist, and for the artist, they see us as the architect.

- ‘Form of Wander’ on the Hillsborough River in Tampa has 3,123 parts that make up its double-layer structure. The green-hued aluminum canopy even withstood Hurricane Michael in 2018. Photo courtesy of Theverymany.

- The centerpiece of this corner of the studio is a prototype for Vaulted Willow (2014, Edmonton), the studio’s first commissioned outdoor permanent pavilion, which proved to be consequential to the direction the studio took from then on. Photo by Noah Kalina.

How did you get into this?

It started in early 2000. Suddenly, at the end of the ’90s, the architect became passionate about the potential of the digital. I started to write code because the tools were not available. Discovering those forms and fabricating them architecturally raised a lot of interesting experimentation and research about how can we actually produce what you call complex forms.

At first I just wrote code, then we started making small proofs of concept, which were a little bit bigger than a model. Little by little, the art world picked up on that. They were more interested in the final products as large models in small installations. Then they became large installations. Then suddenly people were asking us, “Hey, can you do a pop-up store? Can you actually do a permanent one outdoors as a sculpture?” And we grew both the scale and the permanency. So we went from the computations, the nerdy things, to suddenly producing space, and that’s where I think the art and architecture combination came from.

Do you think your pieces reflect the place they are commissioned for?

They are always site-specific. You always serve a different agenda. You need to intrigue and to get attention. You have to find that balance of signaling to the piece, but you need to go to the site and figure out how not to shock people in a negative way. You need to get people to collectively appropriate the piece because if it doesn’t make any sense in the site people will just reject it.

A big part of our process about the site is the research. We think, “How can we do it more efficiently?” so the next time we can be faster and cheaper and bigger.

How can we generate public engagement, but not just have people like it and say it’s nice, it’s beautiful, but how can it be a magnet for children? We want children to run to it and interact with it and have the parents follow them and then talk about it to their friends. In order to do this, the piece needs to have that signal aspect. It needs to be a little different.

The introverted part, that’s my day at the office, that’s the research. That’s where I play with scale and shape. That’s where I try to figure out how to make these organic pieces that are structurally sufficient. How can I achieve that cheap, fast, et cetera?

In our Dumbo studio we live among prototypes. The traces of past work and research take up more space than we do. It’s both a necessity of storage, to have this kind of grotto of full-scale models, but it’s also important for us to operate within our accumulated knowledge base. When making decisions about current projects, we constantly refer to techniques, strategies, and the lessons of the work around us.’ Photo by Noah Kalina.

Nine spherical forms come together in a continuous surface in Marc’s ‘Double Agent White.’ Photo courtesy of Theverymany.

Is there ever an issue with the weather or environment, considering you have pieces by the sea and in parks?

We get this question all the time from clients. Is it climbable? Is it weather-resistant?

We went through the slow process of going from nerdy guys in front of computers to creating models to creating temporary to creating permanent indoors to creating permanent outdoors. Every year we pass a new test. I think five years ago we beat the first one, which was an outdoor space with a specific wind tunnel. Two years later we figured out how to create a piece that would survive a very salty environment. Last year we completed a project to withstand a Category 4 hurricane in Florida and our first very large facade—dramatic scaling.

Every year we keep meeting those little challenges, which also means we have to reinvent something. For me, not just the growth in scale is important, but also making sure the pieces aren’t just decoration. We want the art to augment the feel of the space. You can put the most beautiful piece of art in a space, but after seeing it two or three times, you stop looking at it. We really focus on the engagement aspect. Architecture is the same. Too many buildings are just, you don’t even notice them. They don’t change the way you experience space.

A perfect example: We did a piece five years ago in Canada, in Edmonton, and when we opened the gate around the piece when it was complete, we saw a group, it was maybe about 10 children, and they just ran into it. We thought that was nice, but then what happened next was the parents ran behind the kids. At first they were a little bit concerned, the piece looks extremely thin. Is it safe? And then they started to play with the kids inside. And what was really nice was it seemed like those parents must’ve told all their friends, and those friends brought their kids. That piece got so much attention, and still, today, every weekend there are people posting their pictures with it. It’s not just the typical Instagram. They’re posting with their dog, their cat, they’re posting their kids playing, their wedding. That piece has affected the city. That’s what we’re after with every piece. Whatever the program, the scale, we try to generate that kind of interaction.

It was impossible not to interact with the 2014 ‘Situation Room’ installation in NYC. The lightweight, ultra-thin self-supported shell structure was augmented by artist Jana Winderen’s engineered sounds. The structure combined 20 spheres of incremental diameters to create an envelope of experiential tension.

‘Boolean Operator,’ a large-scale outdoor pavilion (bottom), was installed at the Suzhou Center for the Jinji Lake Biennial in China. Photo courtesy of Theverymany.

Are you ever able to make something without a client?

As part of the architectural process, the client is more the decision-maker, and in the art process, the artist is the primary decision-maker. We are often much more our own client than the client themselves. Most of the time, if we are convinced about the piece, convincing the client is not that hard. We still have to convince the client in a lot of different ways from the technical side to the safety side to the colors. Are they going to go for fluorescent pink? Those aspects come from the architectural side. Still, we tend to have much more freedom. We don’t have the ménage à trois of client, architect, and contractor. We cut out the contractor part, it’s just us and the client. That simplifies the process. I think it helps that the clients often come to us because they want the element of surprise.

Have you had any bad experiences?

Every project is a series of challenges, but more so personal challenges. One that comes to mind is a piece we did in Kazakhstan. We had to build a structure for a world exhibition, yet it also had to be a permanent piece. It was an incredibly fast process, like six months in the country on the other side of the world. We arrived in February, where it was -20C. There was the different language, the different alphabet, a different political context, where at one point they wanted to take the passport of everyone. A good quality to have is coming in every day to the office and saying, “Whatever happens, it’s OK.” There’s a solution to every problem.

“It’s a strange existence, in a way, because for the architect, they see us as the artist, and for the artist, they see us as the architect.”

Do other people in the design world inspire you?

We’re very self-introverted. We learn from tests, trial and error, correcting and redoing, growing works, growing in scale tests, more trial and error, redoing, prototyping, et cetera. Because it’s research-based, we are very much centered around our problem—how can we bring finesse? How can we make it as light as possible? How can we make it as fast as possible? That drives a lot of the work we do. And that’s why across the temporary to permanent designs there’s a certain consistency. It is because it is very self-involved.

Of course you have to be aware of culture, and so yes, we’re aware of what’s happening in the art world, what’s happening in architecture. We’re not totally in a submarine. I did work quite a bit for a Zaha Hadid architect before, and I think if there would be one character who did put some ignition to that and is always very supportive of the work is the new director, and his name is Patrik Schumacher. We stayed in contact and I taught with him. He is somebody who has been supportive.

Do you ever find it challenging to be in the U.S. as a designer?

Good question. I studied quite a bit in many different places, and traveled quite a bit before I ended up in London, where I began working. At some point, I knew it wasn’t where I wanted to stay, so I a bit randomly wound up in New York. Because of my interest in those proofs of concept, which relied heavily on new technology, at the time the U.S. was the most advanced place for that, which is not the case anymore. Every school had what we needed. A way to digitally cut, a laser cutter, a 3D printer. The U.S. also allowed me access to the U.S. market. If you are not based in the U.S., it’s much harder. Plus, being European, I still have access to the European market.

An interesting thing: Everything here in New York is liability-based. You can do anything you want, but if ever it turns south, you better have a good lawyer. In Europe, it’s a little bit the opposite. You have many barriers up-front that the word liability never really translates.

But for me, new technology at the time, and we’re talking 15 years in the past, is what attracted me. The availability of it was economically cheaper to produce. Now, funnily enough, we sometimes produce our projects in Europe and ship them to the U.S. Before we were producing everything in the U.S., emptying our suitcases, putting everything in our suitcases, and flying to Europe.

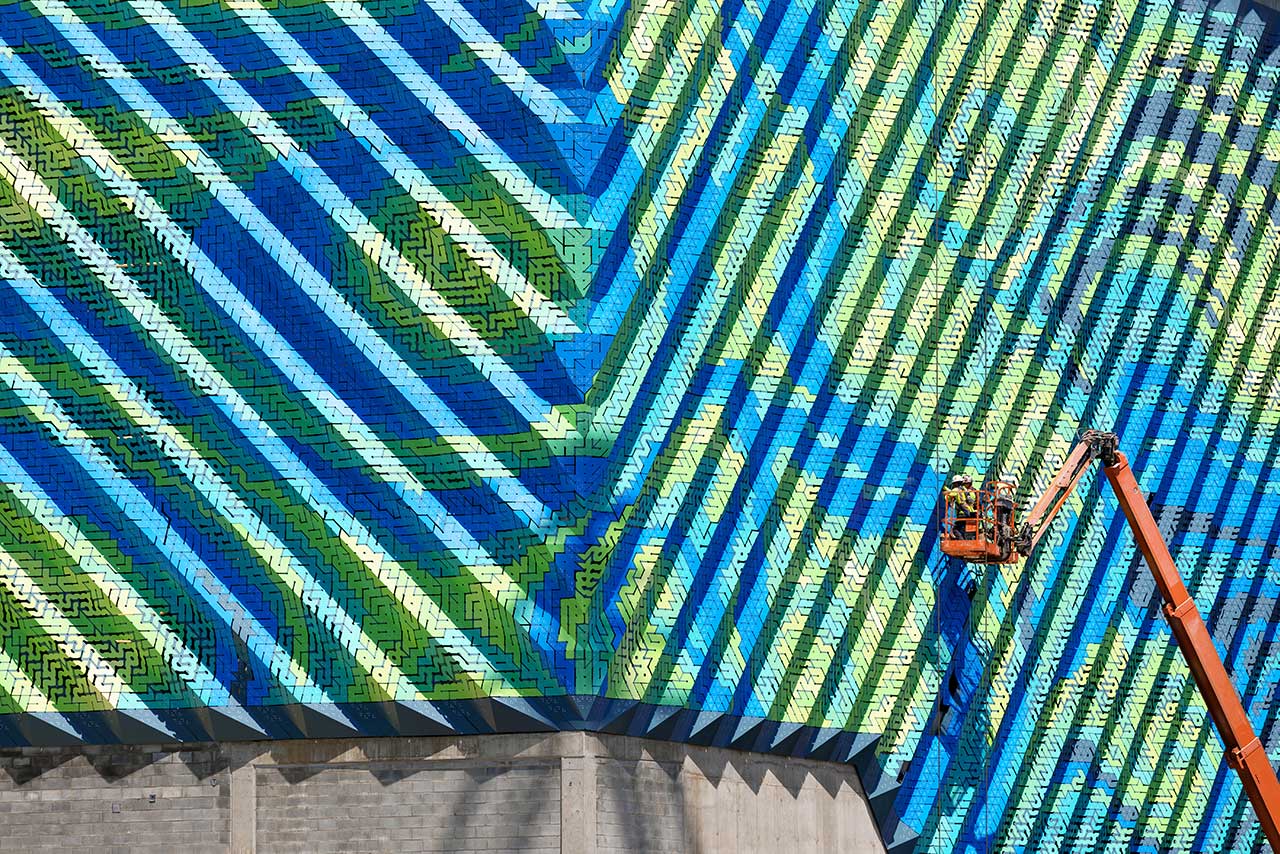

Marc’s public art-meets-architectural skin project ‘Wanderwall’ stretches across eight stories in Charlotte. Photos courtesy of Theverymany.

Is there a standard timeframe for a project?

It’s obviously changing with the scale of the piece. I used to say to people, “Why don’t you come and join me here at the studio? If you work here, in a short amount of time you can experience a very hands-on approach.” Develop a problem and then see it getting built and learn from it because the duration of a project at the time was anywhere within six months. It’s exciting for the young people. Let’s say you stay for a year, you might complete two, three projects. Now since the projects have changed in terms of scope, they become larger and more permanent, it’s different. Sometimes you have to wait, you know the building or structure has to get built before you can put on the facade. Or you have to have the urban development before you can put your piece in place.

Because it’s research-based, we’re not waiting for the commission necessarily to do work. We always have some project that’s already in production, the fabrication, the installation, or some project that needs to be designed, which is the biggest part of what we do. Then we also have a lot of projects within a design competition, where it is much more experimental, where we try ideas.

Timewise, it’s hard to say how long a project takes. Often the idea might have started three projects before, or you take two ideas of different projects and arrange them together. Although there is the timeframe of the client. I like to say that the projects are often born from different seeds.

Photo by Noah Kalina.

Is there a point where you thought, “I’ve made it. I have reached success?”

Today when I get interviewed? [laughs] No. It’s demanding as a job. When you’re so passionate about what you do, giving it your all, you’re dreaming about it, you’re working beyond 9-to-5. But then I have friends who say, “Do you even realize how much you have accomplished in the last five years?” No, you don’t. You’re always after the current challenge and the next one.

There are peaks, which are nice, with different successes or recognition like the one in Edmonton. But it feels more like a moment of success for that specific piece, for a specific moment. We enjoy the engagement and we enjoy the recognition from our peers, but those moments are so ephemeral. I don’t even know which one I prefer. All in all, though, we don’t pause for too long. We just keep focused and keep going.

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of Sixtysix with the headline “Marc Fornes Blurs the Line Between Art and Architecture.” Subscribe today.

Photography assistance by Nicholas Mehedin

Post production by Zach Vitale