Forget the television show. George Lois was there, working on Madison Avenue, famously cranking out controversial covers for Esquire magazine, and creating legendary ad campaigns from the 1960s until he retired in 2000. Ever the straight shooting anti-Don Draper (even now into his 80s), George Lois tells us exactly how it was (and how it wasn’t), and how it is today.

George Lois is a fighter. Literally—he’s a huge fight fan, and he’s fast to assure me that he’s still totally capable of kicking ass in the ring. Or out of it. “I haven’t been in a real fist fight in years,” he says, dreamily. This notorious 80-year-old ad man still boxes, frequents the basketball court, and when he’s feeling frisky, will most definitely rock a pair of pretty darn stylish cowboy boots. No fear. Lois has applied this “just do it” mentality to his entire career. Or, better said in a more Lois-like fashion: “Fuck ‘em.”

George Lois by Noah Kalina

It’s this fight—combined with a brilliant creative mind—that’s made Lois such a force to be reckoned with. He’s always fought hard for his ideas, and as a result, his ad campaigns from the late 1950s and 1960s have become legendary. They broke all the oldschool rules; they were the antithesis of what other agencies were doing at that time. Screw what “the man” says and execute a brilliant idea—even better if it’s controversial. Historians now call this time in advertising “the creative revolution,” and Lois was among those to drive it.

Although some people have referred to Lois as one of the original Mad Men, Lois was not like the type portrayed on TV. He worked at ad agency Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) for a year, and then left to start his own agency, Papert Koenig Lois (PKL), in 1960. His focus there was solely on the work, and there was no time, nor a desire, for three-martini lunches and scads of schmoozing. If a client didn’t like his idea, well, the client could pretty much just shove it.

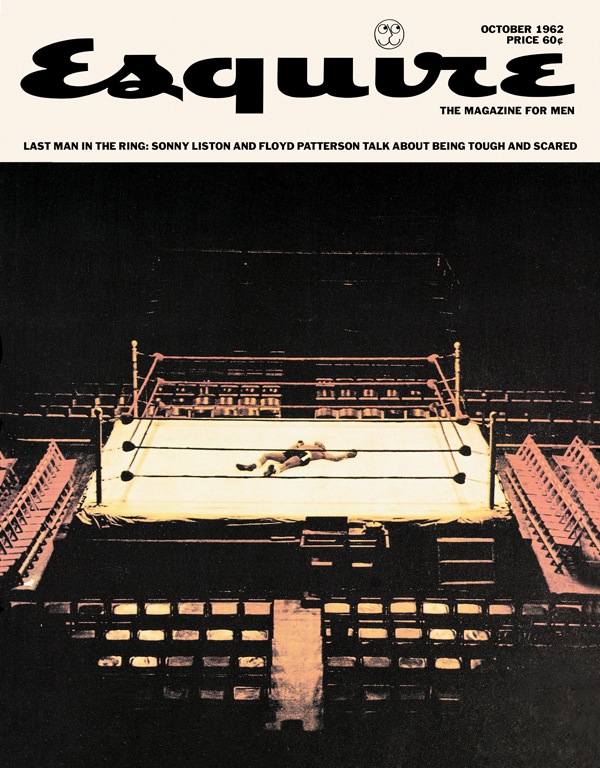

Lois’ first Esquire cover. He lucked out: the mag approved and ran the cover —depicting heavyweight champ Floyd Patterson’s defeat — before the fight took place.

“You have to be able to tell clients when they don’t know shit,” Lois says. “Clients don’t know how to judge good work. The minute a client forces you into doing bad work—that’s it—you’re mediocre. You just gave up the chance to be a great designer.” Sure, any client daring to dismiss a concept was just about guaranteed to get a foul mouthful from Lois, but it was not about his ego. It was about the idea. “You have to be courageous every day in your life,” he says. “If a client thinks it’s too edgy, that means it’s just perfect.”

But clients are not the only ones on the receiving end of Lois’ moxie. Today, it’s his entire profession. “No designer today blows me away (other than a handful of architects) and there is no living artist that I ‘follow’ or think will ever join the pantheon of the greats,” he says. And for being such a prolific ad man, Lois has developed a surprisingly strong distaste for most things advertising. “It’s no good anymore. I never see anything these days where I say, ‘Snap! Mother-fucka.’ There’s just no balls.”

Though designers do get his praise…kind of. “It’s not their fault. There are great designers—the talent is out there. But the problem is, they can’t get anywhere. Designers are handcuffed by editors and salespeople, and they can’t do anything unusual.”

So why were all these poorly abused souls clamoring to work with Lois? It seems surreal—the man who can’t bullshit turns out to be best salesman of all. “People always ask, ‘How’d you get away with it?,” he says. “Well, because my ideas worked. They knocked people on their asses. They made sales explosions. Advertising today is so scared of selling. Don’t be embarrassed about selling something.” According to Lois, his first Xerox television spot had fulfilled the company’s sales goals for the next 15 years in a mere six months. Lois never needed to learn the craft of sweet-talking his clients; they were quick learners. Go with the Lois idea. You’ll make money.

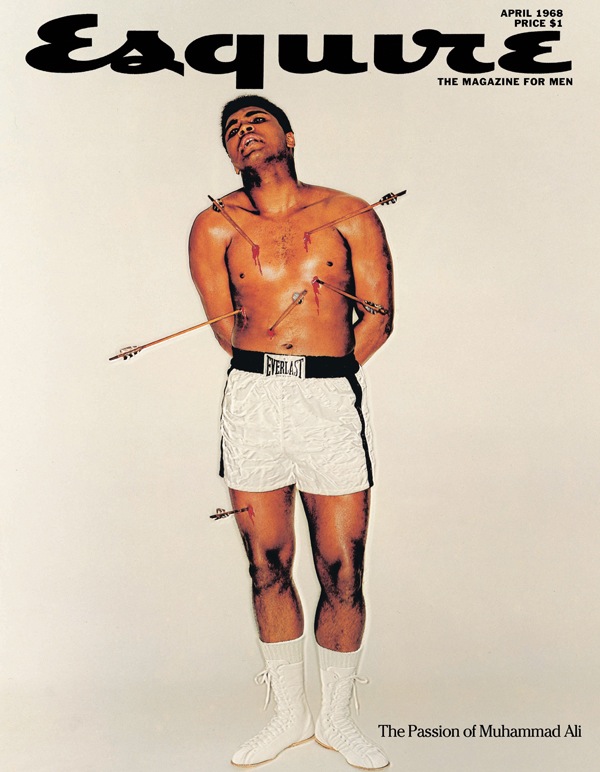

In 1968, Lois made a case for Muhammad Ali’s religious refusal to fight in Vietnam. Inspired by a Francesco Botticini painting, he depicted him as St. Sebastian, a Roman soldier who survived death-by-arrow for converting to Christianity. The Feds didn’t take too kindly to the message.

Those sought-after “sales explosions” in the ad world got him the attention of Esquire magazine, who wanted a piece of the profit pie. His stint designing covers for the magazine started in 1962 and lasted for nine years, but it sure wasn’t because he was such a pleasure to work with. He never provided options for the magazine to choose from and he never accepted direction; in fact, half the time he barely even told them what he was doing. The first five issues were just delivered—completed concepts, no changes allowed— just in time to print. The covers were just that good. And they sold. In 1962, the very first Esquire cover of Lois’ design correctly predicted the unforeseen winner of a major boxing match (Floyd Patterson vs. Sonny Liston). It was so controversial that the publisher added a disclaimer notice to it. But this inaugural hotcake issue sold out, was reprinted, and then that sold out, too.

Lois had an accomplice over at Esquire. Harold Hayes was his editor, whom he held in high regard. “What we had can never be duplicated,” says Lois. “Now Hayes, he had balls. When he looked at that first cover, he said ‘George, you’re crazy.’ And I said no, you’re crazy—because you’re going to run this.” Since the magazine continued to exponentially increase in sales, crazy was clearly working. “Hayes was the only one over at Esquire who actually liked my covers,” he says. “Every single time, he said ‘I love it!’ And I always said ‘Oh yea? Anyone else over there love it?’ No. They all hated them. But Hayes kept me out of all that bullshit. And the art directors over there were smart enough to stay out of something that was working.” But in this case, the do-as-we-damn-well-please duo would learn a painful lesson about playing nice with others, “He left, I left. It sucked. Somebody makes something incredible for you, and then you think you don’t need them anymore,” says Lois, dejectedly. The infamous relationship ended in 1971 when Hayes was pushed out of the magazine, and the pair would only work together once more, many years later, out of posterity. It was inevitable that the magazine would eventually push back, and it was probably more surprising that it lasted for so long. But for the ever-strong man who made magazine covers his passion, this end was perhaps the greatest disappointment of his career. “I would have really loved to do fifty years of Esquire—fifty years of American culture, captured in covers. That would have been amazing.”

“I have always felt creative in every bone in my body, and for every second I’m awake and asleep.”

Lois has been getting extra attention since the Mad Men series began. Everyone wants to know what the greatest real-life ad man (whose younger image bears an uncanny resemblance to Jon Hamm’s Don Draper) thinks about the show. “Mad Men is [an example of ] agencies at their worst,” Lois says. “They were anti-Semitic and racist, they were womanizers, and they had no talent. They were not part of the creative revolution at all. While all that was going on, there were other terrific places to work at, right down the street. At Doyle Dane during the 1950’s, out of twelve writers, six of them would’ve been women. And these weren’t the Mad Men secretaries, they were respected, and they had real talent. We already had women pioneers in advertising in those times. What we were doing was so different from Mad Men, it isn’t even funny.”

George Lois. Photograph by Noah Kalina

His ad agency days are long over since his retirement in 2000, though he continues to be present in the creative world through his writing, and still works on branding and advertising projects with his son, Luke. “I supposedly retired, but my wife says I’m not retired, just tired.” He’s written 10 books now since 1972, all of them containing brassy wisdoms on the things he knows and loves best: Selling explosive ideas, being ballsy, pop culture and celebrities, and of course, boxing.

“Many of my most innovative concepts grew from my ability to understand and respond to the people and events of my era. With that said, I have always felt creative in every bone in my body, and for every second I’m awake and asleep.”

Lois recently took a break from “retirement” to crank out yet another book, this time for Phaidon. They approached him with an idea in mind and a reference: a collection of tips for young people published the year before by a “so-called creative director” at the mega-worldwide advertising agency Saatchi and Saatchi. Lois read it, despised it, and then wrote a response to it called Damn Good Advice (For People with Talent). “All this guy was saying was how to be phony and how to fake your way through life. I want to teach kids how to be original.” No bullshitting—just his style.