Li-Young Lee was born in Jakarta in 1957 to Chinese political exiles and moved to the United States in 1964. He began writing poetry seriously while studying at the University of Pittsburgh, drawing influence from classical Chinese poets and his own experiences. Li-Young’s work is noted for its lyrical intensity, use of silence, and exploration of universal themes through personal narrative, earning him prestigious awards such as the Lamont Poetry Selection (now known as the James Laughlin Award) and the William Carlos Williams Award.

Chris Force: How do you view the role of poetry in navigating the complexities of human existence, particularly in the face of mortality?

Li-Young Lee: On one hand I can’t think of anything better than to try to articulate poetry to the public. There’s nothing deeper, and nothing simpler or harder. The logic of poetry is the most important logic, and the logic of the word is its own logic. Poetry is language in extremis.

It’s what happens to language when it tries to be the most auspicious verbal response to the crisis of mortality, which we face 24/7. We’re preyed upon by time, illness, war, and our own inner demons. Poetry brings extreme order to this chaos, and the practice of the word becomes very important. We’re meditating and regulating death through strong words, forms, and lines. The word becomes crucial, a promise and a name, offering the appropriate response to the crisis at hand now.

We use words all the time, but what’s the difference when we use words in poems? They’re compressed. This compression is noticeable now, perhaps due to social media, where these condensed stanzas or lines are easily shared. The practice of poetry involves understanding why language is compressed. This compression helps poetry mediate and negotiate the chaos of existence, acting as a form of regulation or mediation of death. While it’s impossible to fully achieve this, poets throughout history, like the Chinese Tang Dynasty poets, have approached it. As long as humans continue to read we’ll cherish those attempts.

Do you ever consider the difference between love and beauty in your work? Sometimes eloquence is mistaken for beauty, like in a great speech, but beauty isn’t always present in love or in the things we write about it.

Love for me is like a chi—not a subject, but a presence. Beauty is an important metric, but I don’t think you should shoot for it. Instead, focus on bringing the right intention, even though intention might not be enough. Love is the highest interest, especially in the outcome of the other, which might be a deeper form of love than just the desire or the satisfaction they bring us.

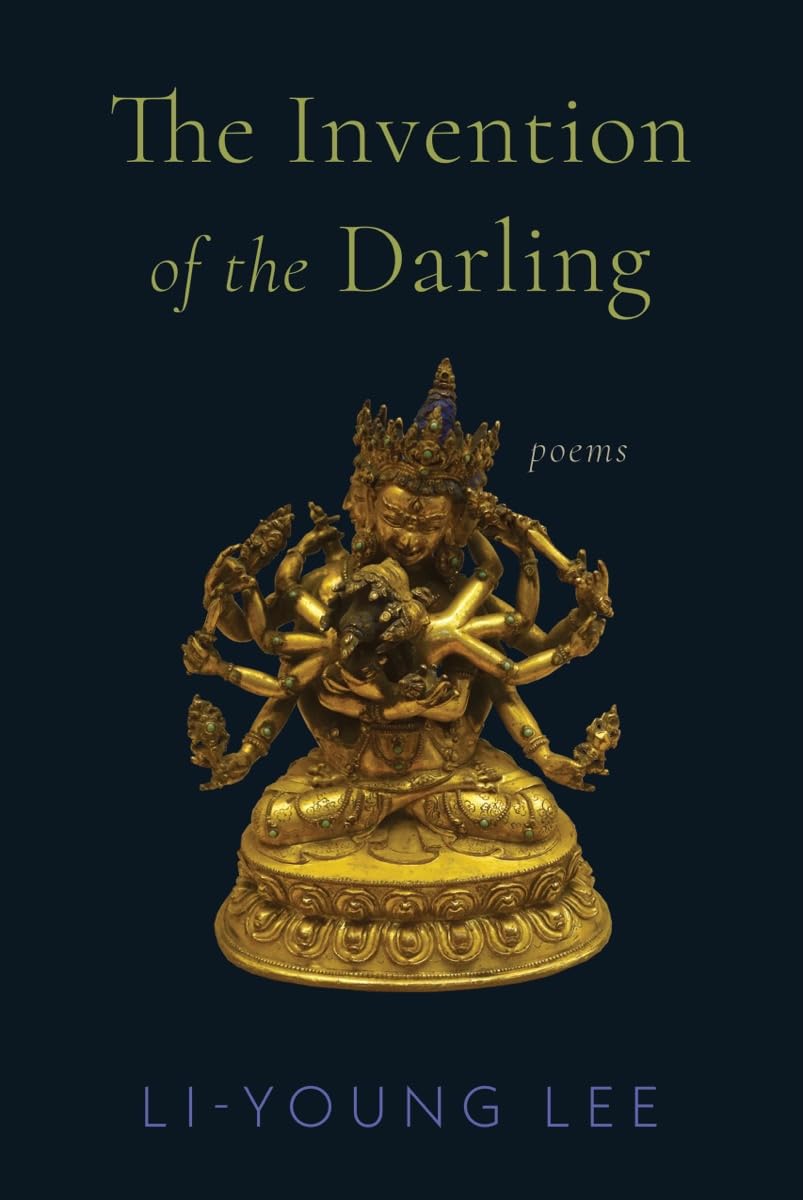

In Li-Young’s The Invention of the Darling (Norton, $26) the poet moves between the role of son, father, lover, disciple, and teacher and a rigorous insistence on apophatic ways of knowing.

Your work and thoughts seem rooted in a spiritual or religious context, where questioning the purpose and investigating the highest level is normal. How do you build a career from a timeframe and aspiration that seems out of sync with modern goals of popularity and quick success?

I live in my own head and talk with my family and friends, often pondering the relationship between form and void. A body moving is in motion because it’s pushing against something. Language is pushing against the void by creating extreme forms, which accentuate the void, leaving us in a state of quotable silence. The mystery of quotability is codified; it must be rhythmically sound. The texture needs to be interesting.

Making forms in poetry is crucial—a dance between form and the formless, life, and death. That’s the deepest mystery, isn’t it? How did Shakespeare do it? How did Levi do it? How did Dickinson do it? All of these poets share this quality of quotability. There’s something about the silence before and after their words.

It’s like a secret—a quality you could try to list or bottle up, but you can’t quite capture it. I am only now realizing how important making forms is. For the longest time I thought I was drawn to the formless or the open, but now I see I was obsessed with form, too.

However, I struggle with deadlines and distractions, sometimes needing to disengage from my work to find the light of life elsewhere. I have this book that’s coming out, and I’m starting to think I should have held on to it longer. My approach has been to disengage myself from it. I feel like that’s the light, that’s enough, that’s life.

I have other poems that are still interesting to me, even if I may never publish them. The publication part is a rewarding inconvenience. It’s complicated; the publication of the poem isn’t necessarily the most meaningful part.

When you put a specific group of topics together, does that involve some sort of architecture or planning to structure all of this out?

Yes, and the difficulty for me is that the architectures change. Long poems try to discover and enact the architecture of change in a longer period, while shorter poems focus on the architecture of change in a shorter span. I’m nervous about codifying these ideas too soon. When it’s published it feels codified, which is why I’m hesitant about teaching. Teaching requires codifying your thoughts, but then you’re locked in. What if your thoughts change by Friday? I’d come in and say, “You know what I said on Monday? I’m not sure I believe that.” You have to stay open.

MY SWEET ACCOMPANIST

By Li-Young Lee

A boy becomes a young man in an instant.

But not before he learns to say yes to life

is to say yes to death.

To say no to death

is to say no to living.

Excerpted from The Undressing: Poems by Li-Young Lee. Copyright © 2018 by Li-Young Lee. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

How do you navigate deadlines and the discipline needed to write and sign off on the final poem selects amidst the distractions of your mind’s exploration?

I’m so bad at that. When my editor gave me deadlines for my upcoming book, I met the first one, and she made some suggestions. Then I decided to rewrite the entire book in a week following the pattern that already existed and that I trusted. I was hoping to unearth deeper patterns if I went through it one more time, using the pressure of the publication. I just wanted to peel back one more layer, and I did that. But I also knew I could fuck it up so bad. After the fact I couldn’t believe I had done it. I was afraid to look at it. I asked myself, “What am I in this for? Isn’t that what I’m in this for?”

How do you navigate the tension between confidence and self-doubt in your creative process, especially in a field as unconventional as poetry?

I’ve gotten so much support from my wife Donna, the rest of my family, so many people, but poetry is hard. It’s hard, but it’s great, too. I’m terrified right now because I feel I finally understand what poetry is. I just hope there’s enough time for me to write some. It’s taken me all this time to understand the importance of form.

Poetry is language—the best form in the worst chaos. The extremity of those two things accounts for poetry’s compression, its hardness. You can knock on it and reveal a truth to it that is deeper than words. Great poems push against the “all” to inflect it, in order for us to experience the great enormity, silence, and immensity of the “all.” That silence has qualities of immensity, qualities of murkiness or brightness, or too much brightness or darkness. Form is an answer to these qualities, but it is a mystery.

“I’m terrified right now because I feel I finally understand what poetry is. I just hope there’s enough time for me to write some.”

Are your children creatives?

They are, for better or for worse. They’re all creatives working in different mediums. The youngest one is a painter and a chef. My oldest one is a writer. They’re all struggling with this. Sometimes I want to ask them, “Are you wrestling with God? Do you have death on one shoulder and eternity on the other when you’re sitting there? You need to feel the weight of all this and have the courage to throw it all off and create something.” I have sometimes blurted those things out and regretted it.

I think I did that just the other day. My son, he’s this wonderful painter. A gallery owner really liked his work and mentioned a few moves he made that he thought were interesting and evocative. Nothing but praise. I had to ask him, “You’re not just doing this to be interesting and evocative, right?” After the novelty of interesting and evocative wears off, there still has to be something underneath it. He said, “I’m doing my best.” Now I’m thinking back—what a thing to say!

How do you envision the idealized version of your poems that are not yet realized?

I think about it this way: Even before the artist shows their work to somebody, and that person thinks it needs something added or removed, I want to ask, “Where do they get the feeling it needs this?” Or they say, “I need to remove that.” Where did they get the feeling that they needed to remove it? They must see two things. This is the only way I can think about it. They must see the painting they’re looking at, and at the same time, lurking in that painting, the painting they want. I think it might be useful to think of it that way.

I want to know—where do they get that second thing that’s not there? That second thing is the first thing, because that thing is the second thing that doesn’t look like the first thing. Are they trying to make it perfect? Is that a higher, a truer incarnation? Is that what we’re trying to do anyway, part of our own becoming, looking at ourselves and thinking, “Though I’m this ball of flaws and potential, I can become something coherent?” Where do we get that feeling? What is that second thing the person is looking at?

Is that what you felt when you read through your first draft of this book?

Yes, I’m trying to adjust my eye so I can see that book—not just the book that’s coming out. I’ve been hunting for that book my whole life. The poems are getting closer and closer, but the mood is so immediate.

Do you think completing this book will bring you a sense of completion in your creative journey?

I hope so. This whole thing is a distraction. Sometimes I feel my whole life has been distracted by contemplating eternity, death, and God. At some point in my life I started finding a way to write about it and get rewarded for it. I thought, OK, everything’s syncing up, but I don’t want to forget. It’s about this contemplative life, if you want to call it that.

If an artist made a blue painting, they would have to solve the problem of which hue of blue to use differently than they solved another painting. It would be a totally different painting that becomes an element in and of itself. You know, maybe the gallerist is saying, “No, just put this on a computer. Pick all these colors, match them.” I’d be thinking, “Oh my God, they think it works that way?”

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 12. Subscribe today