It’s a cool summer night in Monterey. About two-dozen people are sitting on a patio overlooking the ocean, eating desserts, chatting about the news, and telling polite “dad jokes.” It’s a company outing, but it’s got more of a family vibe. They’ve ordered a few extra desserts—mugs stuffed with ice cream and brownies, and rhubarb tarts. Everyone shares. The group’s leader, Christian von Koenigsegg, is across from me in a company polo, blue jeans, and understated loafers. He’s calm, approachable, with a big smile on his face as he works his way through the extra rhubarb tart.

While you might not know it from his relaxed dinner table demeanor, Christian also happens to be the brains behind the world’s fastest car. As CEO and founder of Koenigsegg Automotive AB, the independent Swedish company that redefined the competitive hypercar market, he’s set a new bar for automotive technology, efficiency, and speed.

In some ways it’s hard to be impressed by the technical feats of a car that costs well over $1 million—at that price it would be fair to expect it to fly. But in other ways, what Christian has built is nothing short of amazing. He has no formal engineering degree, and while his family is well off (the company’s logo is based off the von Koenigsegg coat of arms, granted to them in the 12th century by the Holy Roman Empire), he began with comparatively humble beginnings. He got to where he is today from inspiration, single-mindedness, and luck.

This year Koenigsegg created two special versions of its Agera model, fittingly named Thor and Väder. They traveled to Monterey, California, where I was invited to ride along as they entered Exotics on Cannery Row, or “the people’s show” of Monterey Car Week. Thousands of fans line the tight street snapping photos and asking for high-fives as rows of hypercars slowly parade through. I’ve played the role of hanger-on many times in my career, but this is the first where the celebrity is not a person but an object. The “eggs” steal the show—fans are obsessed and flood around Christian when he arrives. After a stint of signing posters and taking photos, we steal away to a hotel lobby to talk about how he got here and where he’s headed.

The world’s fastest production car the Koenigsegg Agera RS. This car was driven by factory driver Niklas Lilja and chieved five new world records in Pahrump, Nevada. It set the record for the fastest speed on a public road at 284 mph. Photo courtesy of Koenigsegg

The Koenigsegg Agera FE (Final Edition.) This one is named Thor, and it definitely stood out in the In-N-Out burger parking lot. Photo by Chris Force

You’re a rockstar out there.

I’ve done this for two years and it’s getting crazier and crazier. I love it though. It’s so good for the brand, but it’s really hard to move around.

What are your thoughts on the relation between success and timing? In your story, there was a huge Scandinavian IT boom that created lots of new investors at the same time you were trying to raise capital. Would you be in the same place you are today if not for “right time, right place?”

I think it’s like this. Luck comes to those who hang around to catch it. I know there were certain pivotal moments that took us to the next level. But if I think about it, there were probably 10 missed opportunities until the right one came along, too.

Do you feel like something would have clicked eventually anyway?

I think so. Looking back at it we had periods where I didn’t have food on the table. But suddenly opportunities start coming. For sure you have to be in the right place at the right time, but you can also miss a lot of opportunities as long as you stick around, tough it out, and catch the next train. But you have to catch the train eventually.

I’ve heard you say this before—the “no food on the table” kind of thing. It’s hard for me to imagine considering how successful the brand is today. What was that struggle really like?

I started my first company when I was 19 and made a decent amount of money. But when I was 22 I decided to go for my car dream, which I’d had since I was 6. The money I made myself took me a little less than a year to get rid of during development, but I managed to borrow a bit of money from the Swedish technical development board, about $200K, and that lasted for a couple of months. My father was an entrepreneur and he sold his stake in a business opportunity he had. He saw what I was doing and my struggle—in the beginning he thought I was crazy to build this car, but he also thought it would be fun to help. So he offered to become an advisor and give us a bridge loan to take us to the next level. He ended up working nearly full-time for us for three to four years, and then we emptied out all his money as well! (laughs)

The One:1 was introduced on 2014. It reaches the ”dream” ratio of 1 horsepower to 1 kilogram of curb weight. Photo by Oskar Bakke

But he must have believed in you?

He almost naively believed anything was possible. I was like, “Dad, don’t put all of your money in this.” And my mother was like, “What are you doing? You don’t have any money left!” He believed it was going to work. I was glad he believed in me, but I didn’t want to put him on the streets either. When I ran out of money a year later, I was even more motivated because he had that faith in me, and now the whole family depended on me succeeding. After three years with absolutely no money, I started doing speeches and seminars.

It’s only mechanics. It’s only physics. We’re not dealing with magic.”

For money?

Yeah, for money, exactly. Then in 1999 we got our first venture capital investment.

How much of those years were working in product development versus trying to raise funds?

50/50. I would have loved to work more on the technical side, but we needed money. I also learned in those years that you can do a lot with no money. You can ask for sponsorship, you can do some things by hand—making drawings is very cheap if you know what to do and do them yourself.

Do you think you would’ve been better off focusing on your core business rather than raising money?

I really think so, because no one was giving us money anyway. The first few years of production were also really tough, hiring people and paying them, getting the volume up. I remember every time we thought, “Wow, we really don’t have any money. How are we going to pay our bills?” that focused me even more on development. If I focused on chasing the money then I’m not focusing my energy on creating something interesting, so it would be worthless. Even though I should chase money and funding, I would rather invent some cool thing for the engine and make it run so someone sees it and gives me money. That was a very important lesson—don’t get caught in the moment of cash flow dips and let that take over mentally and block you from being creative. I remember just becoming more motivated to be creative on the technical side when there was no money at all.

Do you still worry about raising money at all?

The last four to five years have been so different. There was this struggle in the beginning of production, but now it’s become more like a normal business. We’re selling more cars than we can produce, and people want to put down money on cars we haven’t even started developing yet.

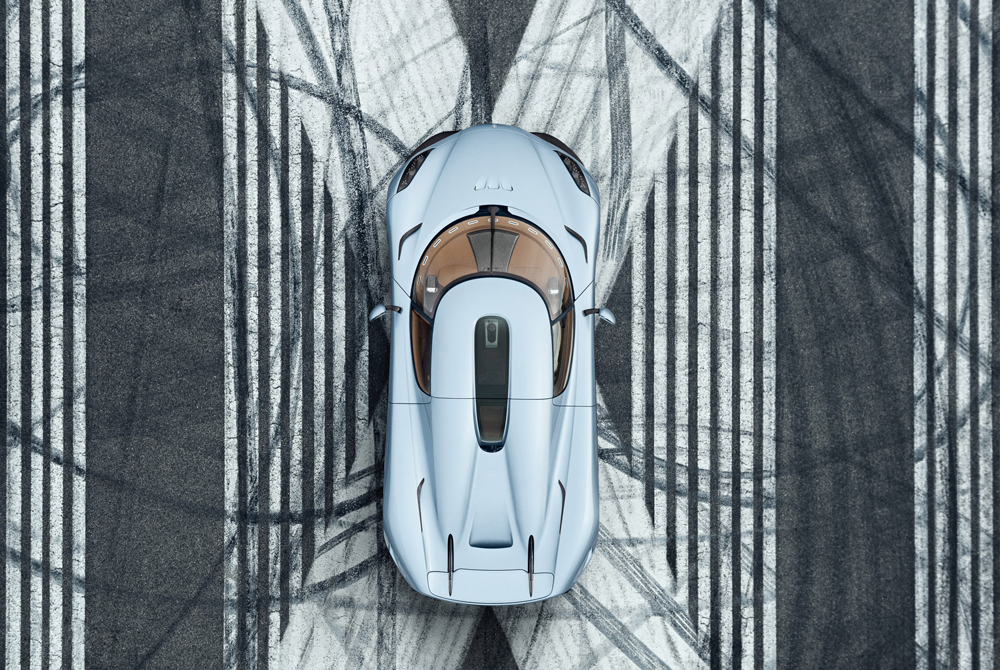

Photo courtesy of Koenigsegg

So let’s say you want to experiment with something, but it’s going to cost a fortune. Do you ever have to say no and make compromises?

For our core business we can do every wild idea we come up with. And right now we’re doing a really wild idea—we’re reinventing the fundamentals of car transmissions. Again! From scratch. No small car manufacturer would ever consider doing that, but that’s what we’re doing for our next product.

How can you do that?

Because we know we have done impossible things before. We just know we’ll get it to work. It’s only mechanics. It’s only physics. We’re not dealing with magic. As human beings we’re pretty good at understanding physics. We’re not so good at understanding dark matter and gravity, but the general mechanical physics of things on earth we’re pretty good at. That’s the only challenge.

You say that, but why is everyone else not doing that?

Because I don’t think they look at it from that perspective. They look at it from the perspective that gearboxes are made by huge transmission companies and that’s who you need to do it, so therefore you can’t. We look at as, “It’s just gears, cogs, oil, and some electronics,” and we know all that stuff.

Do you have interest in other types of cars? Would you make an SUV?

I’ve never liked SUVs. They are so fundamentally flawed. They are cramped for being so big, the floor is so high but no one takes them off-road so the floor shouldn’t be that high. The center of gravity is high so cornering is compromised. The frontal area is large so consumption and speed is compromised; I don’t like the compromise of an SUV. But let’s say, something in that direction of utility and practicality—infusing the performance and DNA of what we’re doing that is interesting.

You’re a Tesla driver. Would you ever make something like a Tesla S?

Ever? Who knows but not in the near future. But something like a mix of that and what we’re doing, something in the middle somewhere.

Photo by Oskar Bakke

What are your other creative interests?

Well, I like to invent things in general. Coming up with new technical solutions for other things than cars. Hmm. I used to write poems when I was younger. I really liked that.

Do you have some favorite poets?

Not really. That’s the thing, I’m not scholared. I just like to write poems, whether anyone thinks they’re any good or not is the question. When I went to school I got interested in poems, but I don’t remember who wrote what. I just noticed that way of expressing myself was interesting.

Do you make time for that anymore?

Not much. More Christmas rhymes. Very little, unfortunately. But I would like to.

How long have you been married?

Since 2000, so 18 years. I met my wife in 1991 when I was 19.

People who are so passionate about their work sometimes aren’t great with relationships. But obviously you’ve found this balance.

Right, well my wife works with me. She is the COO of the company. She’s very involved.

Would it work if she wasn’t?

I don’t know who saved the company the most times. If I’ve saved the company from death 50 times, so has she. She’s been totally instrumental in our survival and us thriving. If she had been a normal employee she wouldn’t have been able to put the blood, sweat, and tears in. For example in the beginning, she called up 50 suppliers and begged them to wait for pay for one month and not send us into bankruptcy. She took care of that. She had good relationships with everyone. They could wait three to four months, and she would say, “We’re so sorry, we’re really trying, we’re waiting for this payment,” and doing that 50 times a day with everyone. That’s torture. No employee would ever put up with that. And she did. So that’s an example. It’s a horrible way of financing a company.

Photo by Oskar Bakke

So what do you do to get away?

We like to get away! It’s mostly boring stuff—beach vacations reading a book. We live by the beach in Sweden. Our factory is in the countryside. We live five minutes away on the beach and we have a little boat, but we don’t really separate work and holiday. I always say, “I’ve never worked a day in my life.” I only work on things I like to do. That also means it’s not so horrible to mix it when you’re always doing it out of passion. It’s not work, it’s passion.

So you never struggle with not having ideas or not wanting to go to work?

Never. I kind of struggle when everything is going smoothly. I’m getting more used to it, but that was not my first 15 years. That’s why we’re creating this new venture so it will be difficult again—so we have something to fight with.

Do you wonder what your legacy will be?

We’ve come up with some cool technical things that have trickled into the car industry. We’ve come up with some really good stuff for making the combustion engine more environmentally friendly and efficient, carbon fiber, blah, blah, blah. But the single most important thing in what I’m doing is, and I hear this all the time, is when people come up to me and say, “Christian, I saw what you did, and nobody thought you could do it. You inspired me because no one thought I could do what I’m doing either and seeing you succeed made me want to do it, too.” Proving that my crazy dream was possible so someone else can do it as well. To make people believe in themselves, that’s the biggest contribution.