It was all about catching Julien Berthier somewhere. That somewhere ended up being on FaceTime at the Vienna International Airport, on the artist’s way back to France after a trip to Belgrade. Luckily it was less crowded than usual. Julien’s plane was late and, for once, the Austrians were to blame.

Against a backdrop of German airport announcements and one very loud baby, Julien settled in for our conversation and admitted he doesn’t really fit the romantic idea many people have of “artist.” He prefers being on the road to being in the studio and, traveling, he likes to spend his stays in the same kinds of places where you’re most likely to find his art—far away from photogenic city centers and more in the remote districts that few people pay attention to.

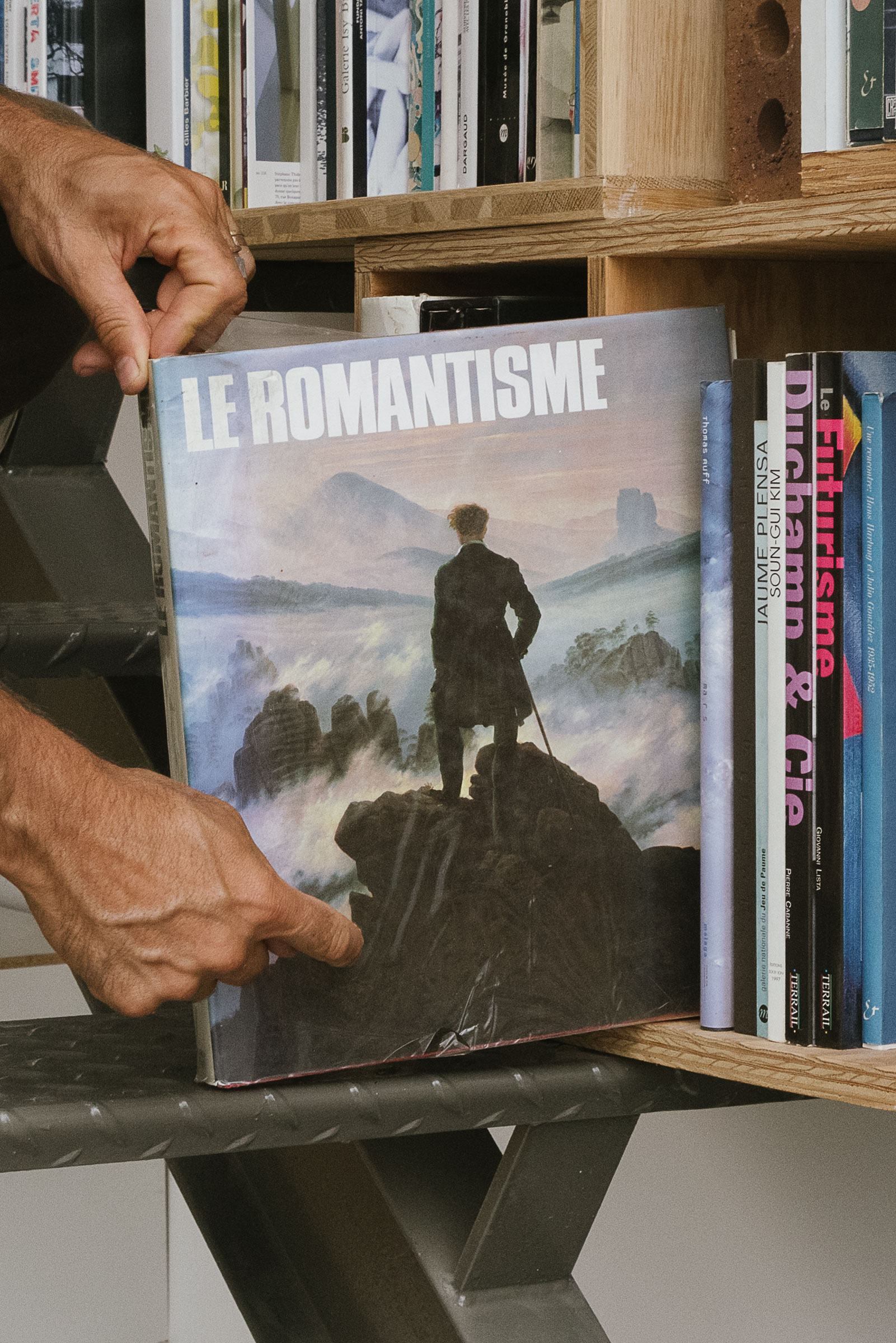

Julien’s been interested in architecture since he was a student at the Beaux-Arts de Paris. Inspired by artists like Gabriel Orozco, Francis Alÿs, and Boris Achour, he said, “I wanted to make art outside of art venues. I wanted to make art in the city.”

On Julien’s recent trip he was surrounded by housing developments designed by young architects who dreamt about modernity after World War II. There he worked, drew in his notepad, made his first watercolor paintings, and even managed to take a vacation.

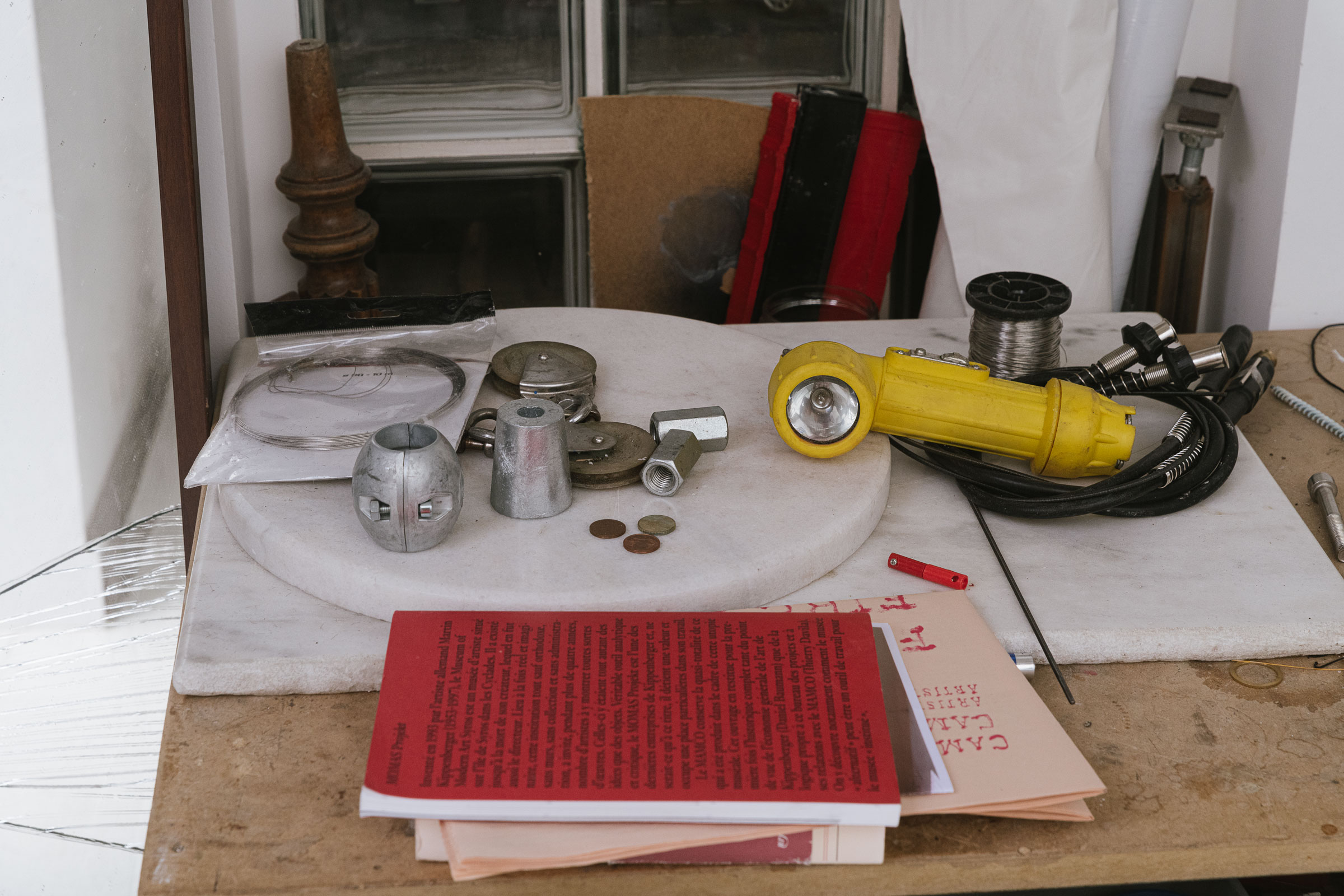

- Julien doesn’t spend much time in his home studio in Paris’ 15th arrondissement; “It’s near Charles Michels metro station, a communist and member of the Resistance. Not bad, right?” Photo by Chris Force

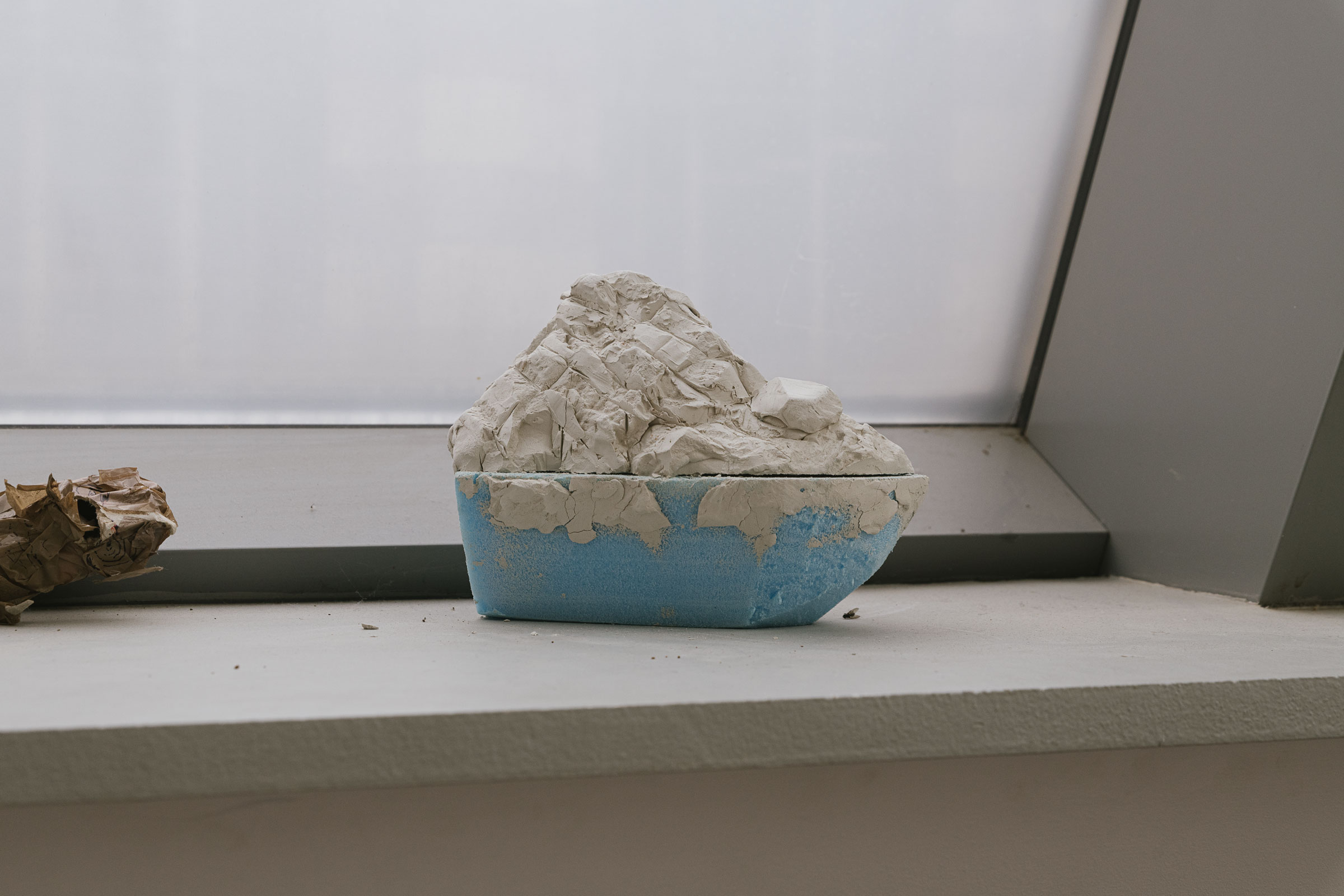

Earlier this year Julien accepted French multimedia artist Thomas Mailaender’s invitation to create an art piece for Tuba Club—a former scuba diving club-turned-stylish hotel in the Marseille neighborhood called Les Goudes. But Julien didn’t want to compete with the city’s natural beauty or make something sensational just to stand out. In fact, he was strongly against it. “That’s what we expect from artists nowadays—to create mediagenic art, appealing to mass media first.” In Marseille, by the Mediterranean Sea, Julien wanted to make something that would fit into the natural landscape. He thought of a boat.

- Photo by Chris Force

- Photo by Chris Force

He got to work on what’s now known as “L’invisible,” buying a dilapidated boat on Le Bon Coin, a popular French website for buying and selling used items. He worked to build his beauty, including its original motor, in Marseille near Thomas’ studio and a local shipyard. “‘L’invisible’ is a real boat, made out of the materials boats are usually made of: polystyrene and resin,” he insisted. The result is a 138-foot-long boat that looks like a moving rock—somewhere between a Tex Avery cartoon and a Jacques Tati film.

- Julien fell in love with the outskirts of cities and Brutalist architecture long before it was trendy on Instagram. He says traveling continues to be what inspires him most. Photo by Chris Force

- Photo by Chris Force

“L’invisible” did camouflage quite nicely in Marseille’s Calanques, the famous steep-sided valleys along the Mediterranean Sea. As soon as it started moving it became an alteration of that very landscape. The work is described as “an artificial rock that can be driven and moved around. It modestly intrudes the environment of Marseille’s creeks and softly modifies its landscape. The invisible navigates between the decor, the enhanced reality, the leisure object, the survivalist anguish, and the ecological stakes.”

- Photo by Chris Force

- Photo by Chris Force

But “L’invisible” is not Julien’s first boat; he built another one back in 2007. The “Love Love” was conceived as a wrecked ship, interpreted by some to be a metaphor for the 2008 financial crisis. “Love Love is the permanent and mobile image of a wrecked ship that has become a functional and safe leisure object,” Julien wrote. “In 2008, due to multiple coincidences, it was installed in front of the Lehmann Brothers building, two days after their bankruptcy. The press, despite my disapproval, saw it as an anticipatory vision of the financial crisis. Yet neither the boat nor the banks disappeared in the following months.”

- “L’invisible, 2021.” Photo by Julien Berthier

- Berthier’s resin boat L’invisible was launched into the Mediterranean Sea. He was inspired by the book, Le Romantisme. Photo by Chris Force

In Julien’s 20-year career as an artist he’s modified centuries-old paintings, made a sculpture from bread crumbs, put bronze pigeons all over Paris, and worked on numerous other projects. He aims to defy strict categorization, working across video, photography, sculpture, drawing, and installation to create unusual but functional works that question perspective.

Eventually Julien’s plane to go home arrived, cutting short a conversation that had switched back to Belgrade’s crazy buildings and could probably have gone on for hours. After the Serbian suburbs and a quick jaunt home, Julien was headed to the Pyrenees mountains with his son to camp out under the stars.

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 07 with the headline “Julien Berthier.” Subscribe today.