Bookmaker Irma Boom’s Amsterdam studio is on a tree-lined street bathed in dappled light. There she owns a pair of stately brick townhouses bridged by an eclectic three-story structure composed entirely of glass, concrete, and steel. One-part studio, one-part library and gallery, Irma’s space mirrors her approach to bookmaking—defying convention, drawing strength from history, and full of joy in the sheer act of creation.

Some would call her work avant-garde, but that’s not her phrase. “The way I make books refers very much to the beginning of printing, to the Gutenberg. What I’ve realized is that I’m actually going back to how it started.”

- Irma Boom won the Johannes Vermeer Award in 2014 and used the 100,000 euros to start a library. Photo by Bram Belloni

- Irma Boom has also won the Gutenberg Prize of Leipzig City for outstanding services to the advancement of the book arts. Photo by Bram Belloni

Irma has been called the queen of books, though she humbly refuses the title. Her work has appeared in the Pompidou Center and the Museum of Modern Art’s collection, and, among many other accolades, she won the Gutenberg Prize of Leipzig City for outstanding services to the advancement of the book arts. And yet, she says she’s still experimenting.

“I’m still trying. Trying to get somewhere, to develop the whole notion of what a book is,” Irma says. “That was, from the very first moment, what I was experimenting with. In the beginning I didn’t know anything. Now I know just a little bit more.”

Irma’s studio space is organic and functional. Every choice is intentional, from the cool white interior to the treatment of the large windows—some glazed to allow light in yet ensure privacy, others floor to ceiling and unobstructed, offering a framed snapshot of the life below.

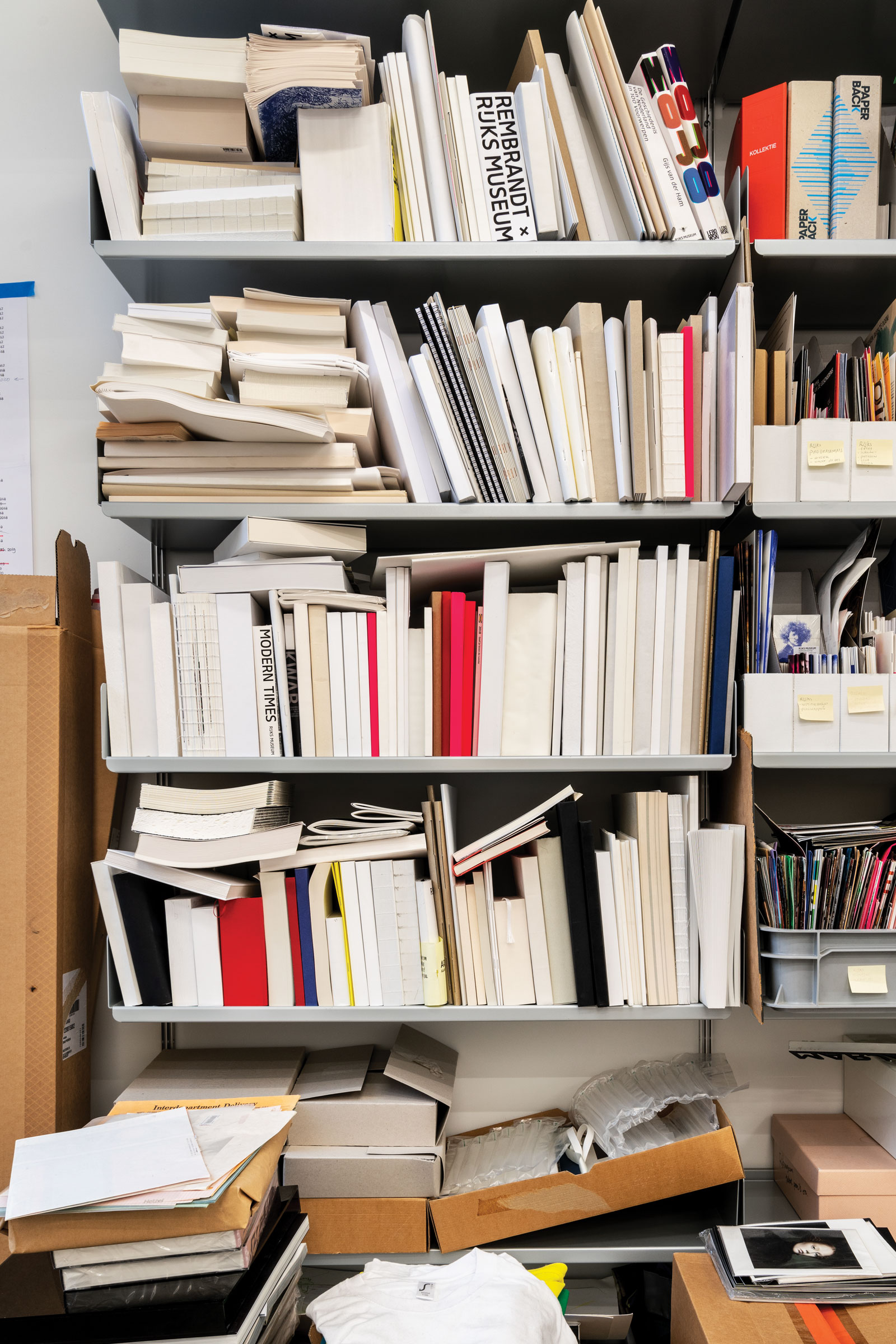

- Inside bookmaker Irma Boom’s Amsterdam studio. Photo by Bram Belloni

In her small office, surrounded by stacks of papers and books, Irma takes the reign on every assignment, steers every project, shapes every design. Although she has two assistants (Jan and Emma), she doesn’t delegate like a boss. “If I make a book, I do it completely myself, including typesetting and corrections. I don’t let somebody else execute it. That’s not the idea. During the making so many decisions have to be made.”

She says having a smaller, more intimate space to work within keeps her close to the work, close to the process of creation. “Imagine if my office was big. Then I would have to do things I don’t like. And now I only do things I want to spend time on.”

- Irma surrounds herself with things she adores in her office and library in Amsterdam. Photo by Bram Belloni

- Working material fills Irma’s tables, including samples wrapped in brown paper and some of the current books she’s reading. Photo by Bram Belloni

Irma surrounds herself with things she adores, but her space is quiet—a stark, modern contrast to the lush greens and red brick of the residential street outside her windows. That feeling of quiet—inspiring a museum-like introspection—permeates her process as well. She prefers to work in silence, drawing inspiration from within and from her growing library of rare and unconventional books.

When she works on a project, she does her own typesetting and sits on the editorial board, choosing authors, photographers, and book structures. “I don’t work for people; I work with them. I collaborate.” When I speak with her in November she’s working on a Ray Johnson book for the Art Institute of Chicago. She also doesn’t offload much, if anything.

“I’m not a manager, telling people what to do. People say I work like an artist, but I’m a bookmaker. I am a soloist. I am autonomous. I work 24/7.”

Although she refuses to call herself an artist, she acknowledges her artistic beginnings at one of the most liberal art schools in the Netherlands. Irma grew up in the Netherlands in the 1960s, the youngest of nine siblings. She enrolled at AKI Academy of Art & Design to become a painter. But after three-and-a-half years she thought it wasn’t a good fit. So she dabbled in photography, architecture, drawing, until, quite by chance, she dropped into a lecture on book design.

“I met this teacher who would talk about books. He would have a table of books in front of him and explain why certain books look like they do—pocket-sized books, novels, poetry books, atlases. He would recite from these books, and that triggered me. He also explained that the best books were those where content and form come together.”

She decided to try to make some herself. She interned at the Dutch Government Publishing and Printing Office in The Hague, Studio Dumbar, and then the Dutch Television design department.

Her style was considered unconventional. She mixed typefaces. She experimented. She became something of a household name in the late 1980s after designing catalogs for special edition postage stamps in a convention-defying Japanese-style binding, with text that dripped across multiple pages, printed folds, and translucent paper. She ruffled a few feathers, but the criticism only served to solidify what would become the defining characteristic of her work.

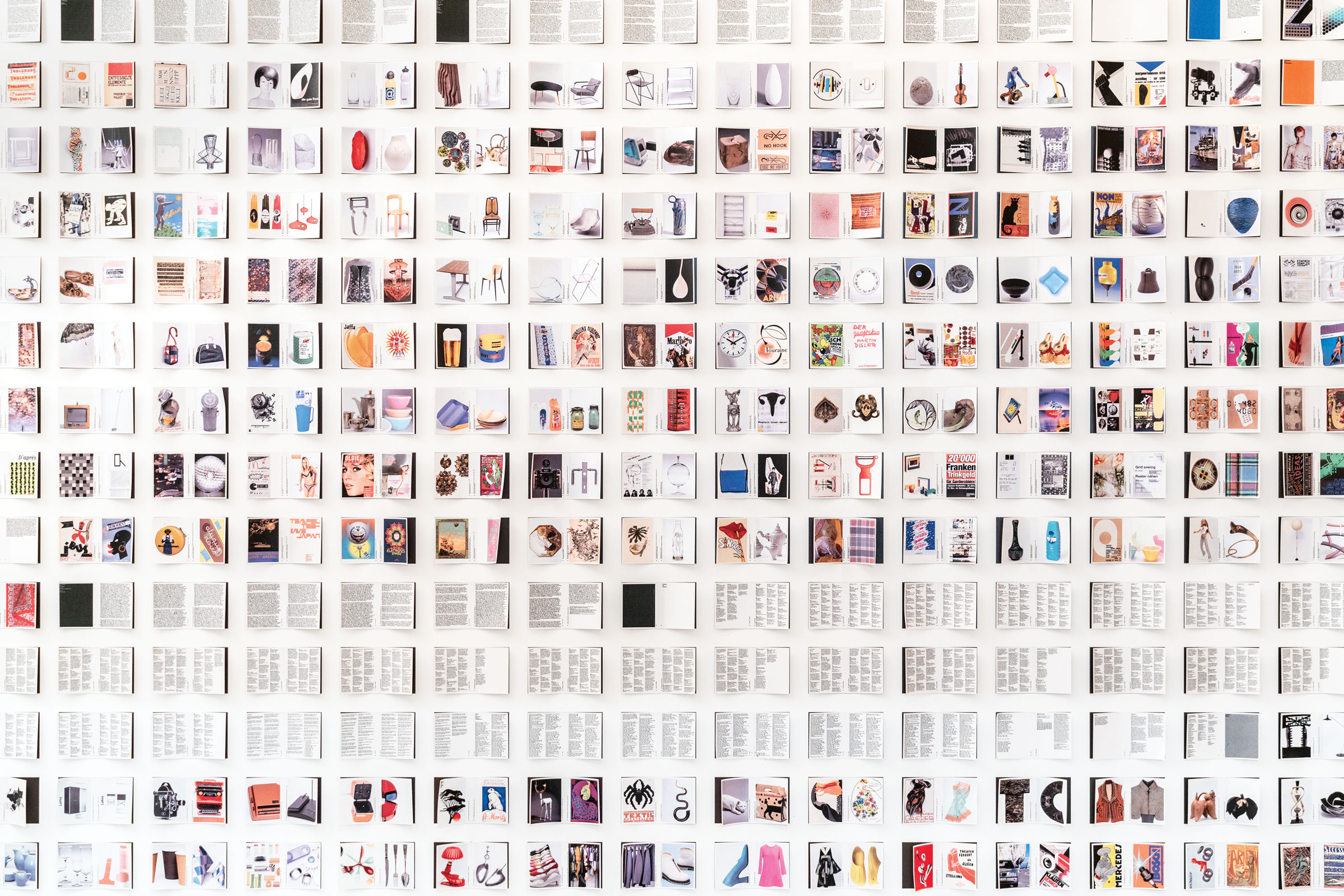

- Irma’s work has appeared in the Pompidou Center and the Museum of Modern Art’s collection, among many other accolades. Photo by Bram Belloni

“We have an idea of what a book is and that’s very conservative,” she says. “I believe it’s important to keep the book alive and to bring the book further.”

Her work exalts the concept of the book, transforms and reimagines it. She has created more than 250 volumes, many of which are now worth thousands of dollars. Pieces like her Chanel No. 5 book, made without a drop of ink, are experiential in their own right.

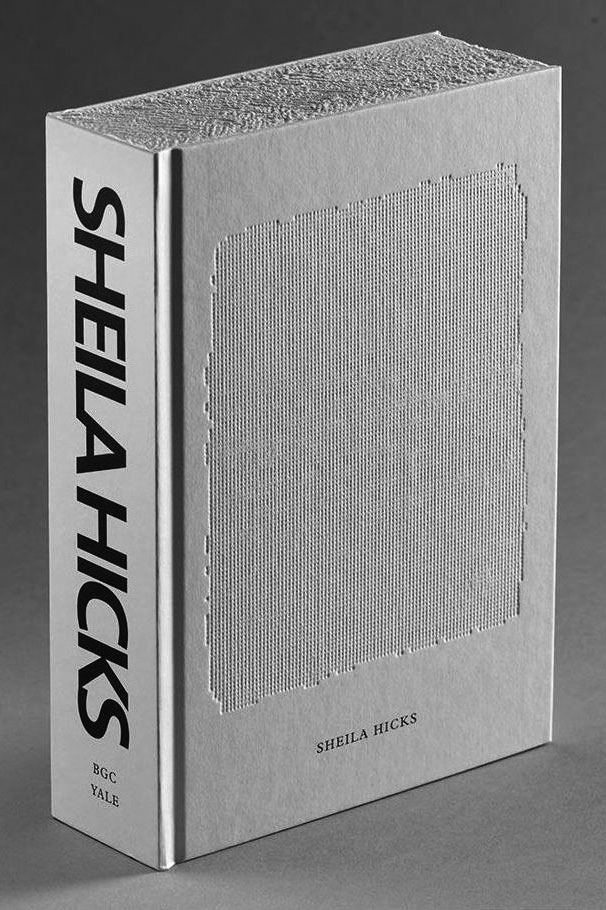

“When Chanel asked me if I wanted to make a book about the perfume Chanel No. 5, I was ecstatic. A perfume is invisible but also very present, so I wanted to make a book that was similarly invisible and yet present,” she says. “The content is not printed with ink but embossed. It is a story how the perfume came into being. The proportion and thickness of the book is also the same as the proportion of the famous bottle. The book is very precisely produced. For me is is the ultimate book; it only works in a physical book.”

- Irma Boom has designed hundreds of books in her career, including Sheila Hicks: Weaving as Metaphor and N°5 Culture Chanel.

- Funded by a 100,000-euro Vermeer Award, Irma’s library is an eclectic assortment of 1960s and ’70s books and tomes from antiquity. Photo by Bram Belloni

Each project is yet another opportunity for Irma to get closer to the core questions that drive her: What is the book? What can it be? She loves to talk about what books are meant to do and examine the ways in which we have strayed far from the book’s original purpose.

“I’m living in a very interesting time as a bookmaker. The internet is in flux, in comparison to making books where the content is unchangeable,” she says. “I think books you make for now and are imported for the future. A book is a frozen entity, a container of thought. It becomes a reference for the future.”

Ask her what she thinks about the claim that the physical book will one day be dead, and she smiles. She isn’t concerned. “Nobody questions why artists still paint, but people always wonder why I still make books. Making books is an integral part of our culture.”

Books, she says, play an essential role in our lives, and she doesn’t expect that to change. In fact, Irma says the physical book is even more vital now, in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, as we become increasingly isolated and reliant on technology. She points to one of her latest projects. “For example, the book and exhibition of which I collaborated with Rem Koolhaas, Countryside, The Future, for the Guggenheim. The exhibition opened in February (2020), and a few weeks later it was closed because of COVID-19. The book traveled all over the world and became the ambassador.”

Irma believes books have unique powers as both works of art and repositories of history, knowledge, culture, and human experience. Before the virus halted most travel, she was spending her time doing research in the Vatican Library, pouring over ancient texts made during what she considers some of the most important eras of bookmaking, when the rules and regulations were blurry at best. These unconventional books have been her inspiration, but she also hopes to use them to cultivate a deeper appreciation for the book arts among the public with her recently opened library.

Irma Boom’s studio is in a pair of townhouses in a residential area of Amsterdam. There she also has her library and an ongoing collection of rare and experimental books dating all the way back to the 1500s. Her partner, gallerist Julius Vermeulen, also has a gallery space there, called EENWERK. Photo by Bram Belloni

That collection, now open to the public by appointment, is located apart but alongside her studio in the same sunny townhouses in Amsterdam. Funded by a 100,000-euro Vermeer Award, the library is an eclectic assortment of 1960s and ’70s books and tomes from antiquity. Students of bookmaking and other artists, writers, and researchers are welcome to immerse themselves in it all, to touch the pages with their bare hands as books were meant to be handled.

“I feel an urgency to talk about and express my role as a bookmaker and to bring the book further. That is my mission. To keep the physical book alive.”

Although the library is new, gathering the books has been a lifetime labor of love. Some of her favorites include a 1970s art book by the late Ellsworth Kelly; a 1969 catalog for Andy Warhol’s first exhibition in Europe; and a 1974 volume by the Swiss artist Dieter Roth. She also collects pieces from the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries. She’s been collecting books for a long time.

“I am building a library with early printed books and books from the 1960s and the beginning of the ’70s. These are two moments in bookmaking where there were no conventions; there was freedom. It’s a big inspiration source for my work,” she says.

When she isn’t working on her own groundbreaking pieces, like a new edition of The Book as Exhibition, or collecting pieces for her impressive library, Irma is seeking, always seeking. After the pandemic she can’t wait to get back to the Vatican. She looks forward to creating a new exhibition. She’s calling it Exhibition of the Book. And the next project is always on the horizon.

“Bookmaking is an ongoing process of study. I just keep on going,” she says. “I always think that the best is yet to come.”

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 05 with the headline “Keeping the Book Alive.” Subscribe today.