Hannah Traore wanted to break down the barriers around art and make it more accessible. At 28 years old she transformed her dream into reality, opening her gallery on the Lower East Side. Her inaugural show was a resounding success, capturing the attention of key figures in the art world and marking her as a rising star in New York’s cutthroat art scene.

Suchi Reddy is the founder of Reddymade—an architecture, design, and public art practice based in New York—and has become known for her philosophy of “form follows feeling.” When we gathered for this conversation Suchi and Hannah immediately began to explore the commonalities in their journey. Their conversation is an enlightening exploration of creativity, perseverance, and the power of vision in shaping the world of art and architecture. –Chris Force

- Misha Japanwala’s moldings on the coast of Karachi, Pakistan. The moldings intend to preserve and archive the stories of femme, queer, and trans lives in Pakistan. Photo by Aleena Naqvi

- Misha Japanwala and Hannah Traore at the opening of Beghairati Ki Nishaani: Traces of Shamelessness, a solo exhibition of Misha’s work. Courtesy of Hannah Traore Gallery

Chris: So how did the two of you meet?

Suchi: I had the honor of being selected to do a work at the Smithsonian, which was the centerpiece for a show called “FUTURES.” The curator in charge was Isolde Brielmaier, who it’s been my great honor to get to know and work with. She’s currently the deputy director at the New Museum in New York. Her assistant at the time was our lovely Hannah Traore. Hannah was instrumental in working with me very closely to bring this very complicated work, which we were doing in the midst of the pandemic, to fruition.

I was so impressed with Hannah from day one. She jumped in the middle of this project with so much grace. It was a complex idea with many moving parts that was trying to become physical at a time when we couldn’t make anything physical. We couldn’t see each other. We met on Zoom. As we got to know each other she told me her goal was to start her own gallery. I was incredibly impressed—to be thinking about that at such a young age, now 28, and in New York? New York will eat the weak. It’s just what happens here. It’s not that we mean to do it; it happens.

The fact that she was so young and passionate about making her mark in a world that’s as competitive and as difficult as the art world is, I was just so impressed. Then to see her mission—because her mission is really about amplifying Black and Brown voices and alternative ways of thinking about art and bringing those to the fore so they can be seen and understood in a way that made it not a strange experience for people. To remove this velvet rope that sometimes exists around work that’s from different places made by different people. I was incredibly excited. And of course, she made it happen. She opened an art gallery in the Lower East Side, and her first show was stunning. I had the honor of being the first person to buy an artwork from her first show.

What I’m really excited about, Hannah, is what drove you to do this. Tell me a little bit more.

Hannah: I just want to explain the story a little bit from my perspective, because obviously jumping into a new project, like you said, was so hard. One of the reasons I jumped in so easily was because of you, Suchi, and your team and how welcoming and kind and understanding you all were. You took the time to explain things to me, you made sure I was comfortable and knew what was going on. It was this seamless experience because of you guys. It was a really important project in my life, and I’ve taken that with me.

Something I’ve never told you about was something you said in a talk I came to. I think about it all the time because I think it’s the same with art. You were talking about how architecture completely changes mood. Maybe that sounds obvious to you because that’s your thing, but it really changed my perspective because something I had felt for so long was put into words. I have taken that forward with me. Thank you for that wisdom.

I started the gallery because I love the art world, and when you love something you want to make it better. I saw so many things that were missing and so many conversations that weren’t being had. Instead of complaining about it I felt like I should use the opportunity I had to do something about it. When you were saying I did this for my family, it is very true—the way I grew up, I’m half West African. I’m from Mali, and I grew up in a house with my two parents, my three siblings, and a wild amount of cousins and uncles.

Suchi bought the first piece from Hannah Traore Gallery. “That meant the world to me,” Hannah says, reflecting on the process of building a community of artists and collectors. Photo by Chris Force

S: I’m from India, so same story.

H: It’s the best thing that ever happened to me. Community is this innate thing within me, and I think it is for a lot of immigrants. When I was building the gallery I wanted it to be for my people—to have my people feel comfortable in the space, because like you were saying, that iron curtain is real. It’s sad because galleries should be the most accessible art spaces. They’re free. But because of this iron curtain, this kind of superiority complex, people don’t feel comfortable.

It’s really important to me that people who look like me or people who can relate to the idea of otherness feel comfortable in the space. I want them to feel comfortable showing in the space, feel comfortable buying in the space, feel comfortable being in the space without buying anything or participating in that way at all. That’s how I’ve built the community I’ve built, which is maybe what I’m most proud of about the galleries—the community I’ve built around it. That includes my artists, my collectors, like you, Suchi, buying the first piece. I’ll never forget that. I’m so glad it was you and not anybody else. That meant the world to me.

S: This is why teaching has been an important part of my life for the last five years or so. When you tell me something I said years ago becomes a force in shaping your ethos, those are the things we leave behind.

What was exciting to me was that point of view you brought about in your first show. How are you carrying that forward?

H: I think art doesn’t exist on its own, but galleries like to make it seem like it does. They’re so hesitant to bring in anything, even education, into that space. Museums do a way better job of that. Actually, I have had no experience in galleries. I was a museum girl. So maybe that’s part of the reason as well, but I think about these things, also for me, because I have a brick-and-mortar space. I think to myself, “I want to bring everything I love into that space.” Obviously the main thing is art, but that also includes children.

“It’s really important to me that people who look like me or people who can relate to the idea of otherness feel comfortable in the space.”

I thought I was going to be a teacher until sophomore year of college when I took an art history class. My preschool report card said I wanted to be a teacher, a mom, and a Spice Girl [laughs]. Kids are super important to me. Education is super important to me. I was lucky enough to be able to do an exhibition with students from three schools in the neighborhood ages 3 years old to 15. All the money we made from sales was matched by the gallery and went back to the schools.

Fashion is also really important to me. We’ve done fashion collaborations, and we’re going to continue to do that. And food actually. I’m not sure if you know this about me, but I’m a real foodie. That also has to do with my family and community. I’m about to do a collaboration with a chef with my last name. He’s not related to me, though, Roze Traore. I think part of this comes from the fact that I am trying to bring everything I love into the space, everything I love interacts with art anyway.

S: It’s so exciting for me to hear. My practice includes architecture, art, interior design, art installation, the intersection of neuroscience, whatever it is. Everybody wants you to have a certain voice, and they want you to do the same thing 10 times so they know what to expect from you, so they can put you in a box. But life isn’t lived in a box, right?

These kinds of complicated problems that you and I face as immigrants or as Black and Brown people in a place where we have to carve a voice out for ourselves, are complex. Our problems don’t fit in any box. You need lots of different kinds of people to really be thinking about them.

This idea that art is a part of culture, and art is a part of feeling, and culture actually encompasses people of all ages, people of all kinds is really about community because that’s what it all comes down to in the end. That’s so fascinating to me. I love the example of the school kids’ show, but talk to me about what’s up right now—Quil Lemons from Philadelphia.

H: This is his first solo show at a gallery. He’s known for his commercial work, and a lot of galleries shy away from photographers who are also commercial photographers. I have a friend who’s a commercial photographer and a fine art photographer who says that even after all his success, he still is anxious and still gets shade because he also is in the commercial world.

He’s a good example because he is the cross section of art and fashion and the commercial world and still deserves this beautiful platform. The work is so powerful and strong, and so beautiful, and not commercial at all. If it was that would be OK, too. I had a glass blower in the back room for an installation. She said to me, “I would never usually be in a fine art gallery. I would be in a craft gallery.” The problem with a craft gallery is they don’t care about the conceptual grounding. Why is craft seen as a negative? Why can craft not be in a fine art gallery? It’s all these weird binaries and rules that don’t need to exist.

S: I see that in my world, too. If you do interior design it’s somehow less than architecture. I think that’s so crazy because that’s the first thing people react to and they touch. Architects often sort of close themselves in this jargon that makes what we do inaccessible to people. I think that’s just the wrong way to go about it. Our job should be to make people feel better. That’s our job, to uplift people.

To come back to this idea of fashion, coming to this country at the age of 18 from India, I knew nothing about fashion. I went through this phase of wearing all black all the time. But what I always really liked about fashion, which I find frustrating in architecture, is that it’s represented much better in photographs. Architecture is a three-dimensional thing. You need time and space and movement to really know what you’re looking at. Fashion has a kind of meta thing as well, which is there’s the object and then there’s the person who wears it, and then there’s the image of it, and then how it’s represented, how it makes it into the world. Whether it’s a commercial thing or an artistic thing, on both sides of that spectrum it’s a very interesting trajectory.

I like to bring the discussion of design back to the body because I think this is a democratic space that we all understand without our socioeconomic, political differences; we can all relate here as to how we feel about things. I build my world out of my body, right? The first layer of housing is my clothing. The second layer is maybe my immediate space.

Then it’s my home, then it’s my city, then it’s my country, then it’s the world, then it’s the planet. It’s this trajectory, but there’s a through line to that. I don’t see why any of those layers cannot be designed in fluidity to really understand everything together all at the same time. Each one of those layers has to affect the other one. When people look at things like interior design and fashion as frivolous, I find that to be a troubling trope.

I’ve loved seeing you, by the way, becoming a model and not afraid to say, “Oh, I’m a gallerist and therefore I cannot be known as something else,” but to be broadly proud of who you are and how you express yourself, that’s been amazing to see, at least for me online. How do you feel about that?

H: Day to day my creativity is most used in putting together an outfit, because I do that every day. I find it exciting. When people ask me what my style is, it’s so eclectic because it depends on my mood, but also the way I feel in my apartment. My best friend is studying to be an interior designer. I had my apartment a certain way and the couch a certain way. One day she was like, “We’re changing it.” She switched it around, and it just feels so much better in here. It really does affect the way you move throughout the world if you’re intentional, and I was really intentional about the way I did the architecture and interior design in the gallery. I put curves in, and I wanted it to feel cozy like a hug. I put warm lighting and warm white walls.

It’s interesting that you were saying you loved seeing me out in the world because that has been a struggle for me. I’ve been very insecure about showing that part of me because I think people think if you own a business you must be a serious person. You can’t be a party girl, or you can’t enjoy life. I’ve only been doing this for a year-and-a-half, so yeah I’m going to be really excited if Chanel invites me to a dinner. I’ve struggled because I worry people are going to think that’s what I do all day. But I think it’s more important to just be myself.

S: I think you’re amazing because you’re not letting anything hold you back in terms of how people expect you to be or how they expect you to behave. I think that’s very much in line with not just the ethos of the gallery but also the ethos of the artists you represent. The beautiful thing about being a bit more in public is that you can use that platform to talk about the things you really care about.

- “Arthur Bramhandtam (She/Her), Drag Queen, 2021,” as part of “Gods That Walk Among Us” exhibition by photographer Camila Falquez. Courtesy of Hannah Traore Gallery

- Hannah’s background in museums makes her eager to build a space for everyone—children, craftspeople, educators—despite many of the unspoken rules and red tape of the art world. Hannah Traore outside of her studio in NYC.

H: Someone told me they overheard someone saying that the reason I’ve been successful is because of my “tits and ass.” I hear things like that and it crushes me. I was very insecure about these things at the beginning. I think it’s important, especially for women, to prove we can do both, you know what I mean?

S: If someone says, “It’s all about your tits and ass,” there’s an intention there that’s not useful. That’s not productive. Not to that person or to anybody else in the world. If you say something horrible, you’re affecting the person next to you, and you’re going to affect yourself. Why shouldn’t you be able to show off who you are? Why is that something that is not allowed?

I do want to recognize for a moment the difficulty of being women in the world and doing this kind of thing. Just last night I was looking at an artwork by Doris Salcedo. She did this giant work called Shibboleth, which was an amazing, huge crack in the floor of the Tate Modern, and she lined it with stones from her native space, but she was talking about the ostracizing of immigrants and the way in which immigrants feel other—that you can make yourself visible as a crack in the ground, and you’re going to get backlash.

You are going to get feedback whether you like it or not. I think power is an important thing, to understand the power of your actions and to know your actions have the power to trigger something in somebody. That could be good, that could be bad, that could be a range of things, but the opportunity to affect change exists always within you and everything you do. You have to boldly go out into the world just as you do now and continue to do it.

The other thing I do want to appreciate is that you’re not afraid to express your vulnerability around this. That’s also a really important thing that certainly women in my generation couldn’t even say those kinds of things. There was a time when you would be even more dismissed, working in fields mostly male-driven.

I love my industry, so I really do crave the respect of the industry. What I’ve realized is I just have to be myself and follow my own vision.

H: I think it’s always so important to give credit where credit is due. I’m a young woman who owns a gallery in a very white male space. I couldn’t even probably have opened the gallery without people like you and Isolde paving the way before that, so I know the things I’m going through now, not that they’re not important, but they are miniscule compared to what was going on. A huge part of that I think is that I do have a community to turn to. I have mentors, which is so important, but I also have peers and other young Black women who are doing similar things who I can lean on.

S: One of the reasons why I’m so impressed by you is that I’m a late bloomer. Truly, for many years I didn’t stick my head out of my own practice. I didn’t even look at what anybody else in the world was doing. I just focused on doing my own work. To some degree I didn’t want it influenced by what other people were doing or thinking, so it was quite an insular practice. Then about 10 years ago I began to realize if nobody knew about what I was doing there wouldn’t be a way to expand it. If it can have impact, depending on the scale, now I say yes.

Also, as a person in business you have to accept something’s got to pay the bills and keep the lights on, then you can go and do the poetic things that don’t pay the bills, but keep the lights on for your soul.

C: How do you balance those two things?

S: It is a dance, to be honest. That’s where I’m really grateful I’m an architect because pretty much anything I do can have an impact on the lives of the people that it affects. Sometimes I think no matter what decision I make I’m changing the world. Making something out of nothing, something that didn’t exist before, is a very difficult task. To do that in whatever shape or form keeps me humble and happy. We all try to be profitable while we do that so we can do other things that follow our artistic voices, but it’s a dance, for sure.

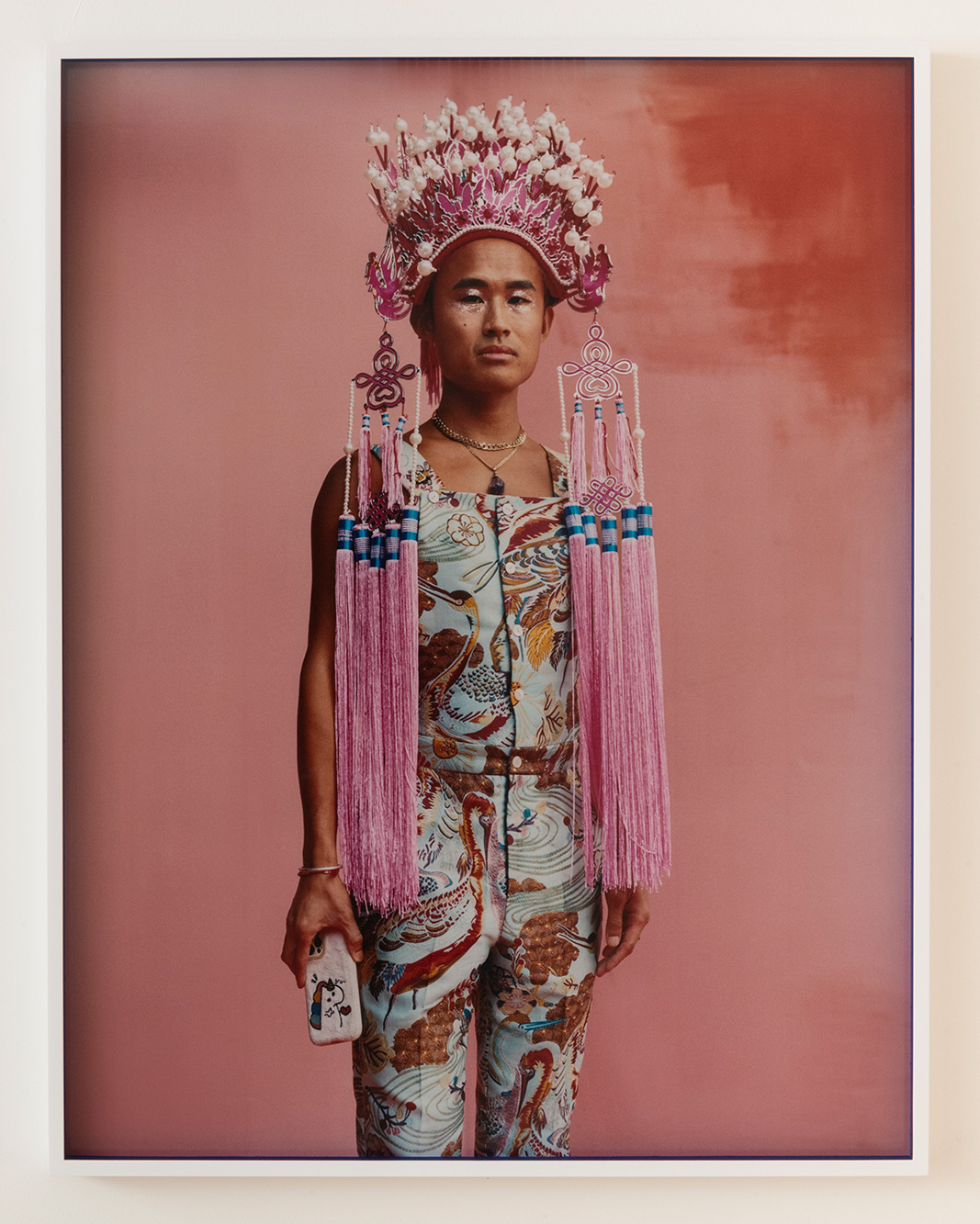

“Qween Jean (She/Her), Costume Designer and Community Organizer, Brooklyn 2022,” as part of “Gods That Walk Among Us” exhibition by Camila Falquez. Courtesy of Hannah Traore Gallery

H: The respect of the industry is something I think about all the time. I’m the type of person, if I don’t like you or respect you, I don’t care what you think of me. But if I respect you and like you, I really am craving your respect. I love my industry, so I really do crave the respect of the industry. What I’ve realized is I just have to be myself and follow my own vision. I’ve had the gallery for a year-and-a-half. The artists I show are wonderful, but their price points aren’t high enough to keep my lights on. I need to find other ways, because even if a show sells really well, I’m not making that much money from it.

The back room right now is a sound and video installation, which is not sellable. I just lost tons of money on that. I lost money on the kids’ show. I did a charity show for an organization called Artistic Noise that helps youth who have been affected by the prison system. These things are very important to me and so what do I do? Honestly, brand partnerships. It is a tough dance because that trickles into me worrying I’m not getting respect because I’m doing these things, but I need those things to fuel the passion project.

S: You are light years ahead of me in this because we’re only just beginning to do that.

H: That’s where the money is.

S: We’re considering which brands we work with. It’s an intentional practice. You do have to be intentional about that and leverage your expertise in the right way.

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 11. Subscribe today.