George Saunders has no problem laughing at himself. Humble, he’s quick to open up about those desperate days as a young writer when he couldn’t seem to get anything right. He’s the type of person who can look back at the last few decades and call a particularly tough time a “blessing” without you rolling your eyes. Because you believe him. It all could have worked out so much differently, he says.

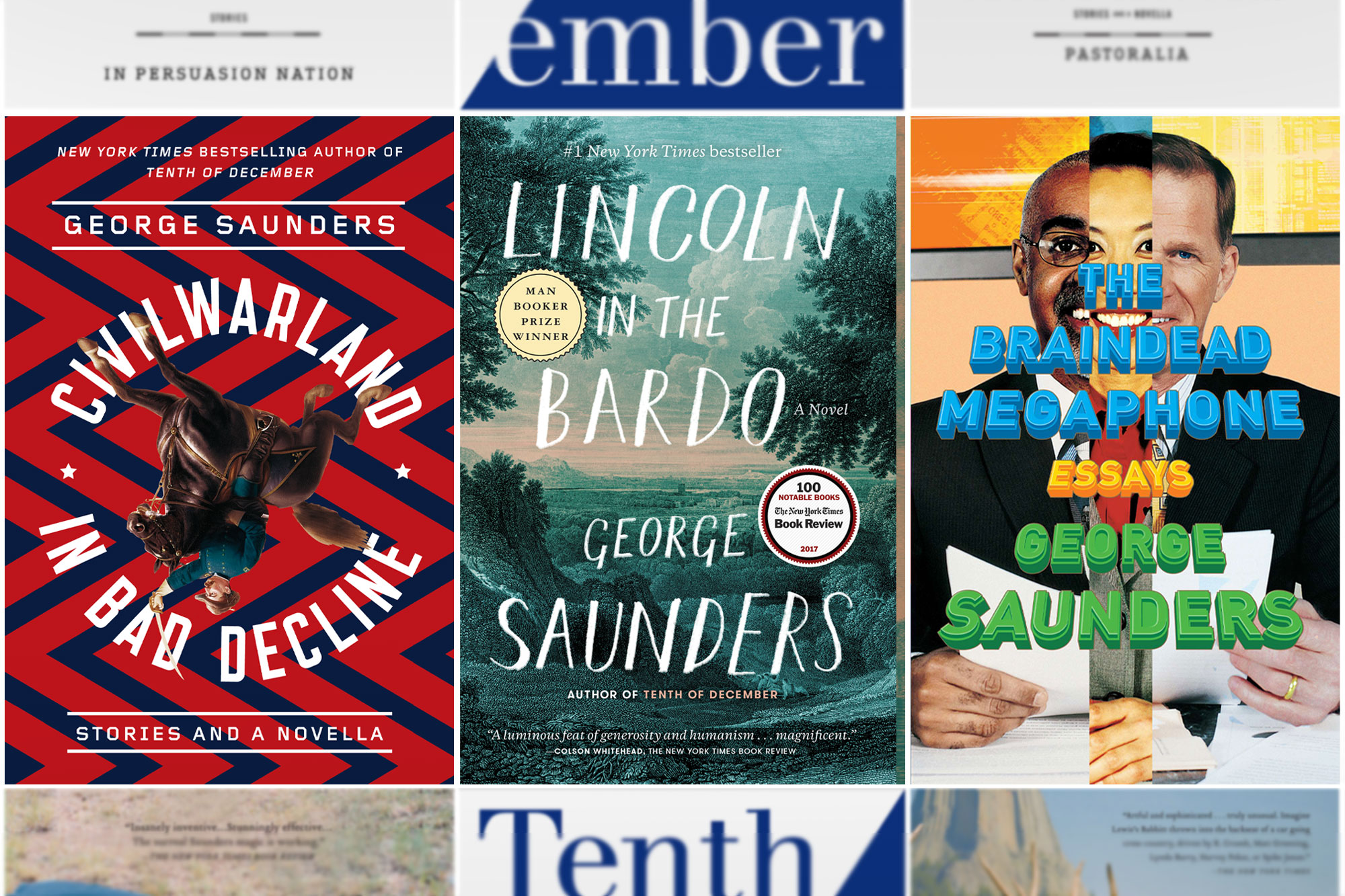

These days, the 2006 MacArthur “genius” grant winner has been coming off of the high that was promoting his debut novel, Lincoln in the Bardo (Random House)—or “that Lincoln book,” as he calls it, though that book earned him the Man Booker Prize for Fiction last year. Most recently he’s been laying a little low and trying not to be “full of shit,” he says, keeping his ego in check while focusing more on writing and teaching (he returned to Syracuse University in the fall). He’s gone back to reading the classics—the Iliad, Shakespeare—while also reading more poetry to shake things up. “I want to make sure I have as big of a lens on my camera as I can,” he says.

George says teaching challenges him in ways he needs. In late August, he was counting down the days until his return to the classroom. “That feeling of being in Syracuse, walking into class knowing your only job is to try to convey some of the wonder of this work of art that you’re teaching to a group of young writers. There’s something so not egotistical about that and sort of centering.”

[rp4wp]

When you see the kind of success he has, it would be easy to get bigheaded; students keep him grounded, as does studying great authors. “Your focus changes just a little bit,” he says of success. “Instead of using art to subjugate your ego and to learn about yourself and to learn about the world in a humble mindset, it can switch a little bit and suddenly you’re using it as your tool to get more stuff for yourself, more attention and more whatever,” he says. He aims to avoid that.

The writing program at Syracuse is strong. George and his colleagues comb through 650 applications to fill six fiction spots. “These people are already off the charts in terms of talent. What you’re trying to do is guide them to that little zone, to where they’re doing the thing only they can do. Of course, that’s not to guarantee you can do that … It’s not just ‘do this’ and then they do it. You’re working with the way their talent actually manifests. It’s really a privilege.”

For George, writing fiction is all about discovery. He resists the urge to know where a story is going in advance. “To know what the story is going to do too well is a buzzkill. Part of my process is to try to think about individual sentences and sections without thinking beyond that, and then improving those small units until they’re kind of sparkly, and then do that again and again,” he says. “Pretty soon the story will start having a theme and politics and all that, but it’s one that will be surprising to you instead of one that you forced into the text.”

When he’s almost done with a piece, he makes small tweaks every day. “Your gaze gets really fine,” he says. “You’re doing these micro adjustments, and then suddenly the story starts to have meaning on an entirely higher level. It’s not that I decided to make it mean more, it just did it on its own. That is really addictive because again, it’s not me coming into the room and saying, “I’m going to be super smart today and make a political point,” but suddenly you just make a point and it really does feel like the story was in there all the time and knew what it wanted to say, but you just weren’t paying attention.” When that happens, he says, it’s beautiful.

What was the biggest challenge for you going into writing Lincoln in the Bardo?

I’d known that story for a long time and I’d wanted to write it, but every time I turned my mind to it I got scared by how “straight” it was—how it was a potentially conventional historical novel—and I thought, “Oh god, you’re giving up all your best gifts if you go into that room.” I was hesitant. I didn’t want to waste a lot of time writing something that would be limp. I tried it as a play for awhile and that really wasn’t working for me. The main thing was just to say that this material is potentially catastrophic; it could be the kind of book you get laughed out of the literary world for, but that was why it was a good idea. I think the hardest thing was just to say, “How do I do this in a way that’s not going to bore me to tears?” The form was really the answer—to do it in the form of those monologues … I tell my students, we do a lot of talk about form and structure, and I think form is the thing that lets you have the most fun. It lets you do the things you’re good at. That’s good form. It’s nothing particularly intellectual, but if you are somebody who is a great dancer to really fast songs, good form would be to not go to a bar where they play a lot of slow songs. Sometimes that seems too easy. One of the psychological traps a lot of young writers get into is they distrust what’s easy. Art has to be this great Saint Sebastian self-torture. It is hard work, but it should be hard but fun work, and work about which you’re fairly excited and have strong opinions about.

What does it look like when you’re writing? Set the scene.

It depends. When we were younger I had a room in the main corridor of the house. I didn’t mind a little noise—the kids could run around and if they wanted to come in they could. Now both places where we live [California and New York] I have a dedicated room. When I was younger I wrote at work. My first book was written at work, so my standards are pretty flexible. Sometimes I write on a plane or in a hotel.

The one thing I have noticed is I like to have a day where there aren’t too many errand-type things or business-type things hanging over my head.

I work on a hard copy with a pencil I sort of obsessively sharpen. I make edits on the hard copy and then when I’ve gotten through a paragraph, the laptop’s on the desk so I’ll pull it forward and put the changes in and print it.

Over my writing life I’ve had all kinds of different little habits, OCD-type things, but it doesn’t really matter what they are, you know? I used to keep a guitar in the room and every so often I’d take a break and play. I had some of this when I used to play in bands—there’s a mindset that falls on you right before you play that you’ve trained yourself in, it’s maybe a 20% concentration increase, so I can pretty much induce that in myself really just by seeing the font I work in. Then I can go, “OK. It’s time to get serious.” But not too serious.

“One of the psychological traps a lot of young writers get into is they distrust what’s easy.”

What font do you work in?

Times Roman, 10 point. The reason is because when I wrote that book at work, the corporate font we always had to work in was Times Roman 12. I started using 10 because I was doing a lot of writing at work so I’d have two documents up on the screen with a toggle set—it was Shift F3 in WordPerfect. It was funny; you could train yourself to respond differently to the 10 point font—fiction—than the 12 point font at work. Over the years I’ve kept that 10 point font as a reminder.

When do you write best?

When I was younger I used to really avoid writing and do it under duress, but now I really crave it so I find I don’t have to have quite as tight a schedule as I used to. It’s what I really wake up wanting to do in the morning anyway.

But in a perfect case, where there’s nothing distracting going on, I would get up at 8 or something and sit down and work until 2 or 3, usually with a break in there. I take whatever I’m working on and do a close revision of it. I put it in the computer and print it out again and just keep doing that as many times as I can manage to do it with clarity in the course of a day. Right now I’m finishing a story so it’s really small changes. For that kind of work it’s best just to do it for an hour or two while you’re sharp so you can get the sound of the story out of your head.

When I was doing the Lincoln book there were days where I’d write for six hours and then research for six and still feel pretty energetic. As I get older the method just consists of having the intent, the desire to do it every day. Also, I feel like time is short. There is a lot to do and I don’t want to not get to it.

Is writers’ block real?

For me it’s not a real thing. The best thing I ever heard about that was from David Foster Wallace. He said writers’ block was just a form of incorrectly heightened expectations of yourself. So you write something and you say, “Oh my god. This doesn’t meet my standards.” And you delete it.

For me, the counterweight to writers’ block is having developed a pretty healthy revision practice, because even then if you write a page of garbage, that’s not a problem. You can revise it until it’s good. If I felt like I had writers’ block I’d just write a page of nonsense and then start tweaking it and saying, “Is there anything in here that has any energy? Oh, there is. OK, there’s four lines. OK, cut the rest of it and start over with those four lines.”

Creativity runs in the family. George’s daughter, Alena, captured this photo of her father while on vacation in Greece.

Does having this hugely successful novel change how you think about yourself as a writer?

The honest answer is that book was a lot of fun. It let me do, or required me to do, some things I hadn’t done before. So mostly I’m just excited. There are a few doors that have been kicked open.

As you write for a long time, and I’m sure this is true in all kinds of art forms, there are phases. In the first phase you’re doing derivative work that doesn’t have much energy. And in my case that went on for quite a long time. Then I had a breakthrough. And now I’m doing something that felt really new and that was getting me attention. That was when the first book came out.

Then there comes a phase where you’re clinging to that because you’re terrified you’ll lose the mojo. You finally got into the party—you don’t want to get kicked out. The tendency is to maybe be a little bit too sure of what you do and resistant to changing it.

This book, for me, was at a time where, at 50 something years old, I started feeling a little constrained by my habits. That book allowed me to kick open some doors. I don’t really care if the next book is a novel or a book of stories, but I want to make sure to keep those doors open that I kicked open. And I’m not exactly sure I could say what they are—something to do with the form, something to do with allowing myself a little wider range of voices. But also it had a little bit to do with saying, “I don’t have to be the life of the party in every line.” Now that runs directly contrary to what I learned way back when, which is, “You have to be the life of the party in every line.” So then you get into that enviable artistic space where you’re really not sure. I feel very nicely confused right now.

Did you always want to be a writer?

If I look back I can see that that kid wanted to be a writer, but he didn’t know it was such a thing. There weren’t a lot of role models, so I think until I got to college I wouldn’t have ever said I wanted to be a writer. But then it was like Hemingway. It was that admiration of the lifestyle. He was traveling all over and going to wars. I always had some verbal ability. I was kind of a funny kid in high school. I gave the graduation speech, which wasn’t funny, but it was supposedly earnest. It was pretty stupid, but it was well written. I knew I was a pretty good communicator. I could make people like me and I could tell a pretty good story at a party, but those things didn’t seem to me to add up to any natural life. That was just one’s personality. Many years down the line, the magic moment for me was when I realized those things I did naturally to be a human being, to be liked, to get myself out of trouble or make an awkward moment easier, those are the things I was going to use as an artist. When you say it now, it seems obvious.

Was there ever a time when you almost did something else?

There was a time right before I started. I wrote this book I always talk about called La Boda de Eduardo, which was a big, failed novel I wrote when our kids were little. Now it’s a punch line, but at the time it was really painful. I spent about a year on this thing and that was supposed to be my big breakthrough. I gave it to my wife and she read it, or part of it, and it was just like, “Oh, this is not it.” It was really hurtful.

So then, maybe for the first time in my life, I thought, “OK, look. You clearly always wanted to be an artist, you always wanted attention and to have a form. You’ve played music your whole life, so maybe you’ve just been wrong about writing—maybe you’re a musician. So I went and played a couple open mic nights, and I’m not bad, I was probably better then, but I didn’t want it nearly as much as I wanted writing.

You didn’t feel as passionate about music?

Music, I know what I like, but I thought, “I’m never going to be great at this. I might be good at it, or OK at it, but I just don’t have the ferocity that I do with fiction.” Somewhere in there is where I started my first book. There’s some benefit to jettisoning everything else, because I thought maybe I’ll be a comedian or maybe I’ll try to get a radio show. I didn’t know what I was doing. But there’s something really lovely about saying, “Nope. I’m not doing anything but fiction. I’m putting all my eggs in this basket.”

When were those open mic nights?

I was right around 30. We’d had our kids and I was working full-time as a tech writer and you could see the ship leaving the harbor, you know? Like not only did the world not care if I didn’t write, it sort of seemed to prefer that I not write. That was a desperate feeling. I was still in that mode of writing real straight realism. I knew it wasn’t fun. It wasn’t fun to write, and it wasn’t fun to read. Sometimes I think I need a little bit of a rationale to be crazy in my work. Like I need some kind of permission—I don’t know why, maybe it was because I was raised Catholic or working class—but my stories could be very serious unless they needed to be otherwise. In that period, I think desperation is what actually let me do it. I was like, “Fuck, alright. If the world dislikes my work so much I’ll just go a little nuts here.” That was a difficult period. When that Mexico novel [La Boda de Eduardo] failed, that was helpful. I always tell this story, but I had gone into work not long after that and I was on this conference call making these little poems, like Dr. Seuss type poems that were really silly, and suddenly I was like, “These are way better than that Mexico novel. These things that I’m writing in 12 minutes here that are silly have much more life in them than that whole book did.”

It’s crazy how things worked out.

The thing that’s scary is I don’t think that was inevitable. Things just lined up. I’d read Barry Hannah and I’d read some other funny writers who helped me. For a long time I hadn’t really believed in humor. Then, having read those guys and having gotten to the point where my life was comic in a way—I was working at this engineering company as a low-level tech writer-slash-photocopy operator, I couldn’t get anything started, and it was really weird to be at the bottom of the heap feeling like some kind of royalty, but I couldn’t get out of the muck—the correct mode in that life was comedy. That was what I was living. In some ways it was sort of a blessing to, I wouldn’t say I hit bottom, but it was like, “Well, I’m in this corporate office working hard, not getting too many results, and yet this, too, is life. There has to be literature here.” And the literature was funny. And then I was like, “Of course. That’s what Vonnegut was actually saying.” Suddenly it felt like Hemingway was offbase. All that seriousness seemed like the result of privilege. “Yeah, you can go trout fishing in Spain—who’s paying for that?”

[rp4wp]

What other hidden talents do you have?

I’m a pretty good guitar player but in a “music store / that guy’s pretty good” way. It’s nothing special. I like acting, but my outlet for that is to do readings of my own work. That’s fun. I think it might become clear that the more I diversify the less interesting my fiction is going to be. It’s funny—at this stage of your career you get opportunities to diversify. You can cash in a little bit on this or that, and I’m trying to resist that because I didn’t work 35 years on anything but fiction. I record music for myself and for fun … I play now more than ever because I have time and I’ve got equipment. My goal is to someday write one good song, just for myself. But actually what’s useful about it is to remind yourself that shit is hard. For me, writing at this point isn’t hard. It’s difficult but not hard. But to go and try to write a song, I go, “Wow. I really can’t do this. I’m getting in my own way here.” That’s useful for teaching—to remember that it isn’t always clear to the person doing the art how to make it good.

What’s the most incredible thing you’ve been able to do as a writer? Are there times when you think, “I can’t believe I got to do that?”

So many, and that’s a danger. One of the things I think human beings do is when your foot stops hurting, you assume nobody’s foot anywhere is hurting. I have to watch that a little bit because there are a lot of opportunities now.

Your two daughters are creative, too, and your wife, Paula, just released her debut novel. What’s it like to be a family of artists?

It’s sweet. We didn’t realize we were doing it, but when our kids were little we had no money for part of it. I was a tech writer and then I started teaching at Syracuse. We didn’t have any exotica going on in our life. We had two weeks of vacation. What we did have, though, was a reverence for story. When the kids were little we talked about TV and movies and books really seriously in terms of plot dynamics and would get offended if there was an illogical thing in the story. The kids absorbed that in the way that if you were a family of sword-makers you’d be obsessed with swords. We had some of our nicest moments when we didn’t have much money, but we’d take them to New York and we’d see plays. They got to see Philip Seymour Hoffman in Death of a Salesman … Your kids pick up your priorities just by your actions. They’d see us go off to work. We’d be writing all day and they’d come home and find us still at it.

How do you cut through the noise of social media? You seem to avoid it.

Honestly I just get a yucky feeling about it. If I had Instagram or Facebook or Twitter, I know the way my mind would react. My little Catholic mind would always be guilty about not doing enough. The only reason I resist that is I know it would upset my creative life.

If there’s one thing a day I’m doing that’s creative, that thing really benefits from that focus. I know that if I was tweeting, that would suck out part of my energy—how could it not? The joke I always make about it is that I trained myself for all these years to write really slowly for a lot of money, so I resent the idea of writing really quickly.

I think, too, there is something profound, I don’t know if I can articulate it, but I think we’re starting to discover as a culture that there’s a cost to all of this flippancy. Those forms—let’s just say Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter—those forms are corporate forms. They’re designed to look like they’re public utilities, but they’re corporate forms. They’re laced through with corporate prerogatives.

It also means when I go on Twitter, and you’re the recipient of Twitter, we have a very complicated relationship there, which is that I’m throwing an idea off the top of my head at you and you have the right to duck it or whatever, whereas a work of art is something much different. It’s me saying I’m going to spend as long as it takes—three years, 10 years, 12 years—to do something that’s extraordinary that I can’t do off the top of my head, and I’m going to do it in a continual state of respect for you, dear reader.

I think if you graphed the number of social media interactions in the last 10 years, it’s just gone up exponentially, and I think it’s probably carving out a bigger portion of our collective mental and spiritual states. I’m sure there’s a relationship between that and the increasing crassness of our public discourse. My guess is, when we look back 20 years later at this period, we’re going to see ourselves as a bunch of innocents who blundered into this poison Kool-Aid and drank it without thinking because it tastes good. It’s fun and it’s a good way to get a buzz of attention every day, but I’m finding myself more and more against it. I don’t feel like I’m missing out on much actually.

What would you say to young writers who say you have to be on social media today?

Things go viral whether you’re at the bottom of them or not. Like I did that graduation speech [Syracuse Class of 2013] and it went viral. I just gave it to The New York Times and they posted it. But if I was on an island somewhere, it still would have gotten out there. It’s a pretty good medium to make publicity, but I don’t think the writer or the artist has to be at the center of it necessarily. But that’s just me. I’m kind of a Luddite. If I was a singer or something it might be different, but to me, if that’s your form, if writing is your form, I know enough about it to know that what I write in 20 seconds and send out is not as good as what I spend months on. It’s just not.

“I think we’re starting to discover as a culture that there’s a cost to all of this flippancy.”

What do the next couple of years look like for you?

I really don’t know. I’m writing a book of stories and then I’m going to try to come up with one other thing besides that to play with—maybe some nonfiction thing—but I work best when I don’t have a big plan. The Lincoln book was kind of an anomaly. Now I have one story I’m working on and a couple of TV things for fun. And I’m writing this long, stupid poem—I’m not actually a poet.

What I’m doing now honestly is nursing myself back into full writing mode. I feel like I’ve been on the sidelines for the last year or so, so I’m trying to play with a couple of things and get the creative juices flowing. When I finished that Lincoln book, if you think of yourself as a conduit, I had like 100% flow—I could turn my attention to something and just know how to do it. I think from all the touring and talking, the pipe gets a little constricted so you have to clear it out again. For me the best thing is to go back to the story form and start trying to have some fun.

Touring must be fun but exhausting.

It’s exhausting, but it’s also invigorating, maybe in the wrong way. You get a lot of energy and you get a little bit of addiction to the energy. With fiction, you should be able to sit there for seven months and not get any praise. That’s just part of the job, except maybe in your own brain. When you start touring you’re getting so much superficial attention all over the place, and you get addicted to that. And that isn’t actually what you’re supposed to be doing. I’ve been doing this long enough that I can look at myself and go, “Ah, you’re about 40% full of shit. OK, let’s see if we can get that down to 38.”

How do you define success?

It’s freedom, which I’m getting. There are very few minutes of the day where I’m not doing something I like to do or something I need to do on a primary level, like for my family. That’s a big difference from where I was 30 years ago. In that time, there were only selective minutes of a day where I was doing what I wanted.

On a deeper level, the word that comes to mind is fruition—like to have certain dreams or desires you had as a young person and to see them come to fruition is deeply satisfying. Maybe it’s shallow, but to have been an 18-year-old reading Hemingway and saying, “Oh my god, that’s all I want to do with my life,” and then look later and go, “Yeah. You did it.” Not only that but you’ve been respected in the form and maybe pushed it ahead in a couple of places and there’s still time to do more of that, that feels like success as opposed to other times in my life where it felt like all of my efforts were for a company only. Even that I think can be OK, but there’s something about fruition—taking the thing you feel strongest about and making a living out of that is really nice.

The other thing I would say is I take a lot of satisfaction in our family because I know myself and I know I’m a far from perfect person, so to be able to have put together this beautiful family—we’ve always had a lot of love and respect within our family—is a victory. Again, there were times when I was younger when I think you would look at that person and go, “He’s too reckless, too selfish.” When I look back at myself at 27 or 28, if I knew that person I’d go, “I don’t know what’s going to happen to him, but it’s going to be something disreputable.”

But in my world there should be no dancing in the end zone. It’s not over ’til it’s over, and life is hard. It’s difficult. If you can get through a life with a certain amount of happiness and dignity involved—also thinking about this in this “Me Too” moment—to have gotten through your life being respectful of other people, that’s nice. If you can lay claim to that, that’s a good thing.

I’m a Buddhist, so I tend to say let’s not think about success in the past tense. You’ve got a minute coming up and a minute coming up and a minute coming up. It might just be that success is how fully you are inhabiting this next moment and this next one and this next one. And then you’re dead.

Photo courtesy of Alena Saunders

This article originally appeared in the Fall/Winter 2018 issue of Sixtysix. Subscribe today.