Frances Wilks is sitting on her couch staring at a tuft of pubic hair bursting from a woman’s hips. It occupies a full spread in Masterpieces of Erotic Photography, which Frances is fake-reading while the photographer clicks away, capturing her intent focus on the book’s page. Though she is no stranger to nudity or the female body, she can’t help it—a smile breaks across her face and laughter ripples out. “I was pretending to read it for a super long time, and it’s quite a graphic image. We were just laughing for ages about it,” she says when we meet a few days after the photo shoot.

Really, sitting on her sofa at home in London and examining Masterpieces of Erotic Photography isn’t too out of the ordinary. Frances gravitates toward books—from erotic masterpieces to artist monographs to vintage car compilations—for inspiration for her work. She searches the pages for something with complexity that triggers emotion in her, something into which she can infuse her layered aesthetic of beauty and darkness and around which she can build a new world of meaning.

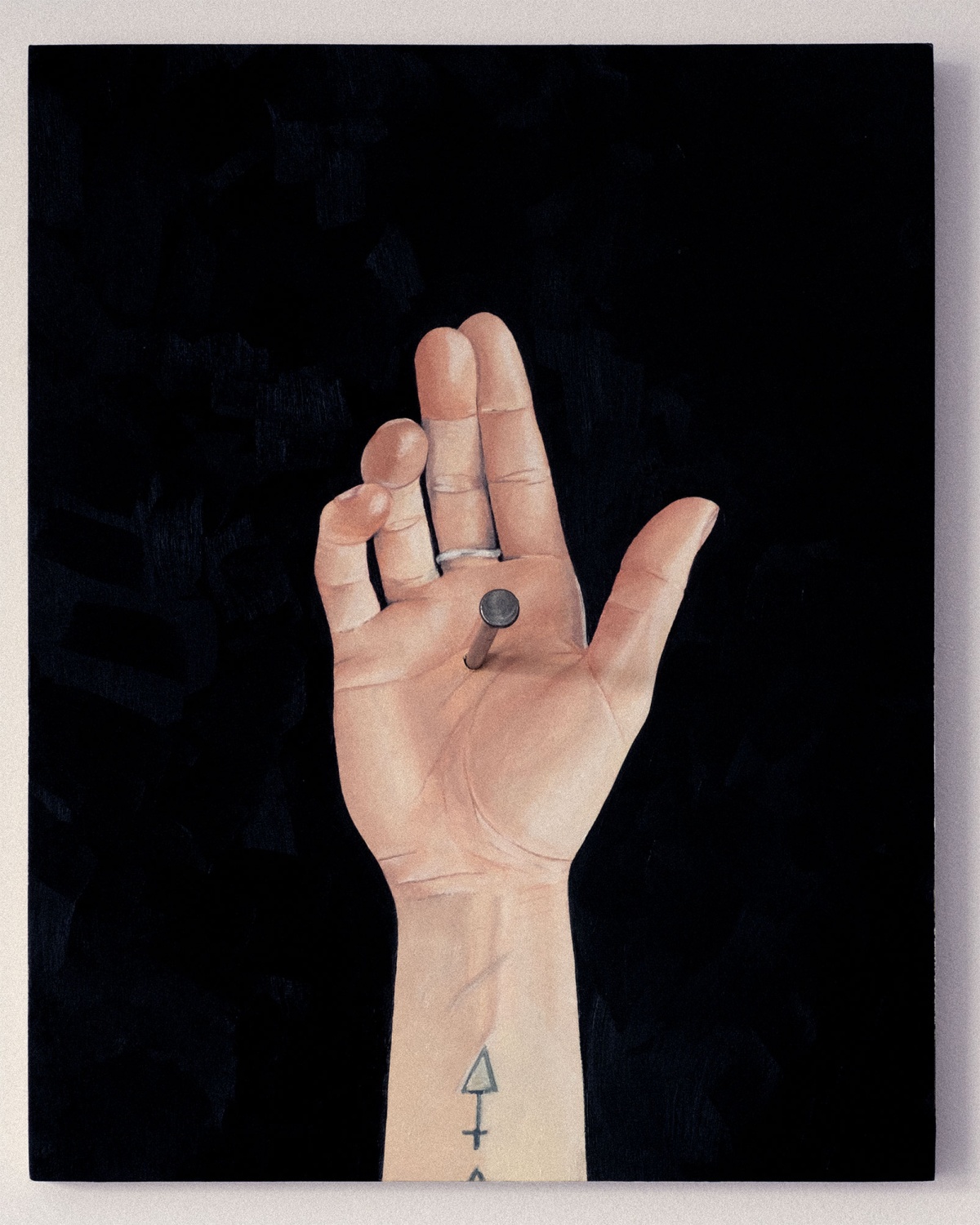

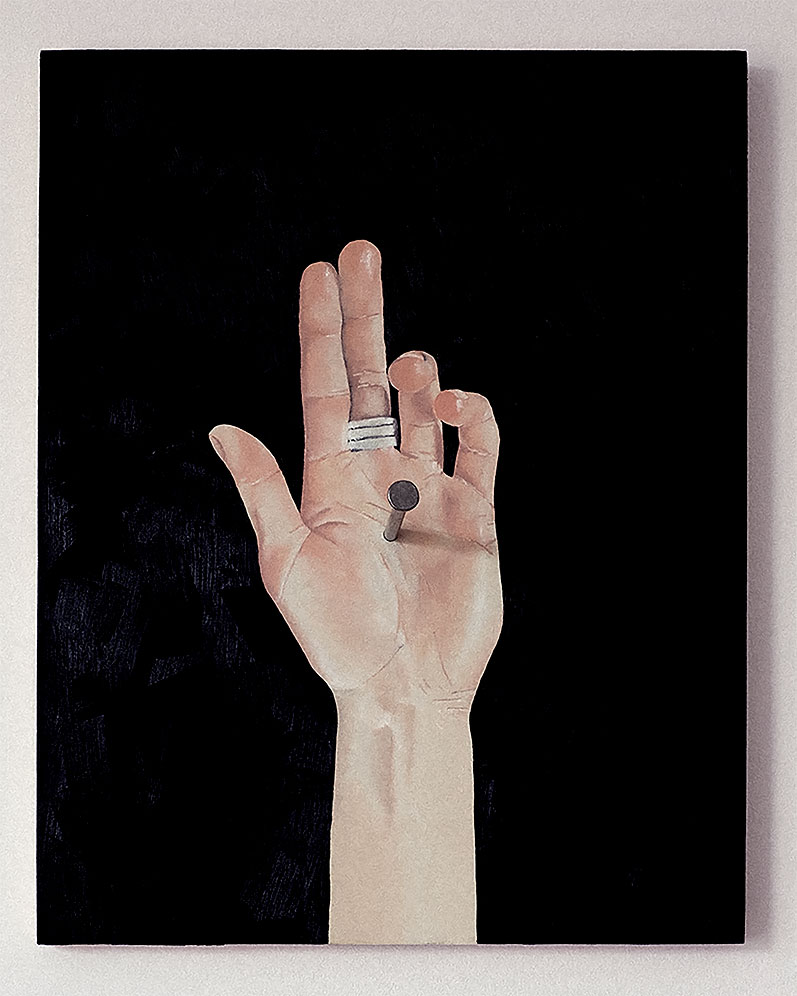

- Similar to Frances’ rendition of Saint Sebastian are “Left hand with 5” nail” (right) and “Right hand with 5” nail” (above)—two paintings violently disrupted by a pointy element. Artwork courtesy of Frances Wilks

- “I wanted to create something sculptural, not just paint on a surface. I wanted to destroy it a little bit, and break it,” she says. Artwork courtesy of Frances Wilks

Trained in graphic design, Frances is a designer and artist, swapping her focus mainly between art direction and painting. She likes the variation in projects, but the balance between the two took some time to find, as she started her creative career in a commercial setting. It didn’t last, as Frances found the world of design for branding and marketing off-putting.

“The idea of creating desire and manipulating desire to sell things, things at the time I didn’t fully believe in or couldn’t buy myself, didn’t really sit well with me,” Frances says. Beginning to paint and working to satisfy her own creative impulses was in many ways a reaction to working commercially. “I wanted to produce something from my own point of view and create a world around that,” Frances says.

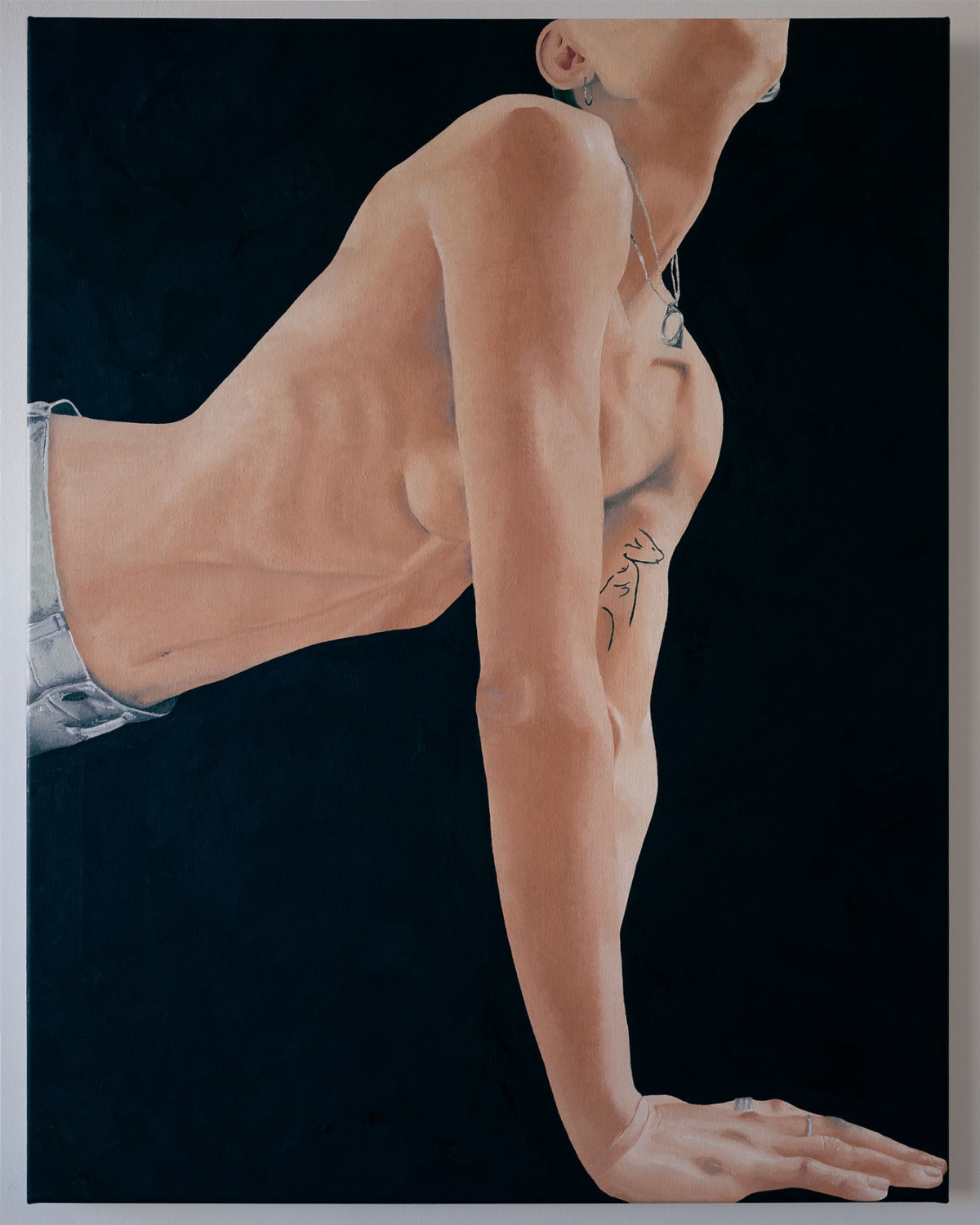

- “Push a Little Harder.” Artwork courtesy of Frances Wilks

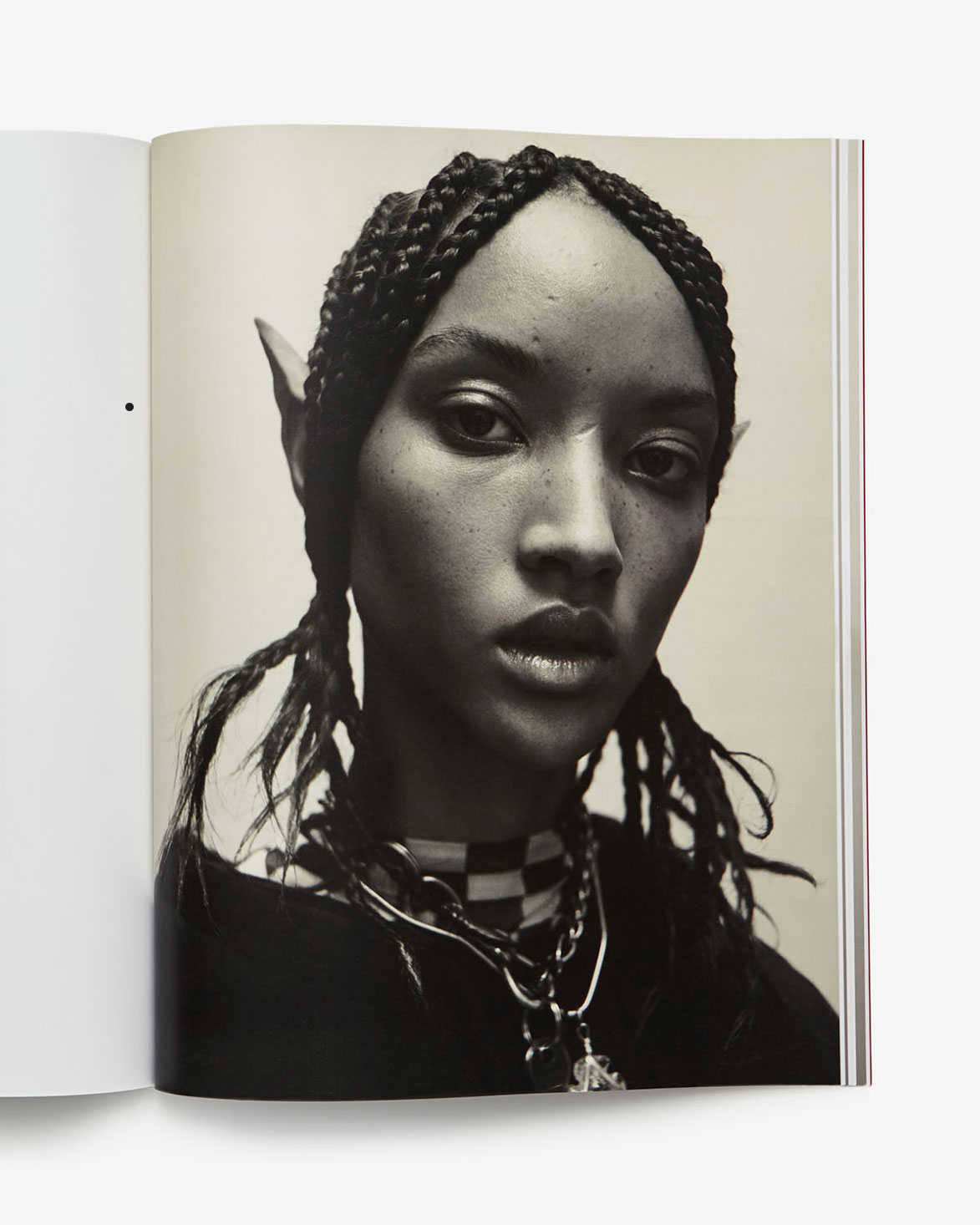

- Portrait of a self-portrait. Photo by Coco Capitán

As she looked around for something worth talking about, she happened upon an old car book full of bright red racecars zooming through the streets of Monaco, covered in sponsor logos. Steeped in wealth and tradition, Ferrari’s Formula 1 team is practically synonymous with the color red and, at least historically, Marlboro cigarettes as a major sponsor—and its fans are notoriously ardent. The rendezvous of a moneyed institution, proximity to death for sport, and passionate audiences under the umbrella of an iconic, fiery red struck Frances. She began working on the project she would title “How to Sell Death to the Living.”

“I guess I like cars, but it’s not something I painted out of a passion for driving,” Frances says. “It was a visual work that compelled me, the idea of danger and speed and all of this super intense graphic imagery.” In stripped back sculptures of Marlboro cigarette packets and self-portraits of herself behind the wheel of a race car and decked out in a racing red fire suit and crash helmet, Frances creates a dialogue between things irresistible and harmful—and things that are both at once.

These themes arise again and again in Frances’ work. “At first you’re drawn to it, but then it’s not just purely aesthetic; there’s something else underneath,” Frances says. “Someone once described me as ‘darkness with a sweet tooth’ which has always stayed with me.”

- Frances and Gino, who she calls “the most chilled dog ever,” stand in front of her Saint Sebastian painting. The work is based on “Saint Sebastian with two Donors” by Antonio Romano, which Frances saw while visiting Palazzo Barberini in Rome. Photo by Lee Whittaker

- “My favorite spot is that table. It’s usually covered in paint and all sorts of crap. I never actually use it as a proper table.” Photo by Lee Whittaker

In a painting inspired by the common depiction of Saint Sebastian, saint of athletes and archery, tied to a tree and shot by arrows, she paints her own body in bluish moonlight and plays with self-destruction using real, three-dimensional arrows to stab her two-dimensional body. “I think I may have had some issues at the time, I don’t know,” Frances laughs. “But I like this idea of self-destruction, and the intersection between masculinity and femininity, disrupting that a little bit as well.”

I ask if she remembers a particular moment in early life when she realized this kind of work was what she wanted to do. “One thing about me is I have quite a terrible memory,” she laughs, but tells me she’s always been artistic, always felt comfortable with a brush in hand.

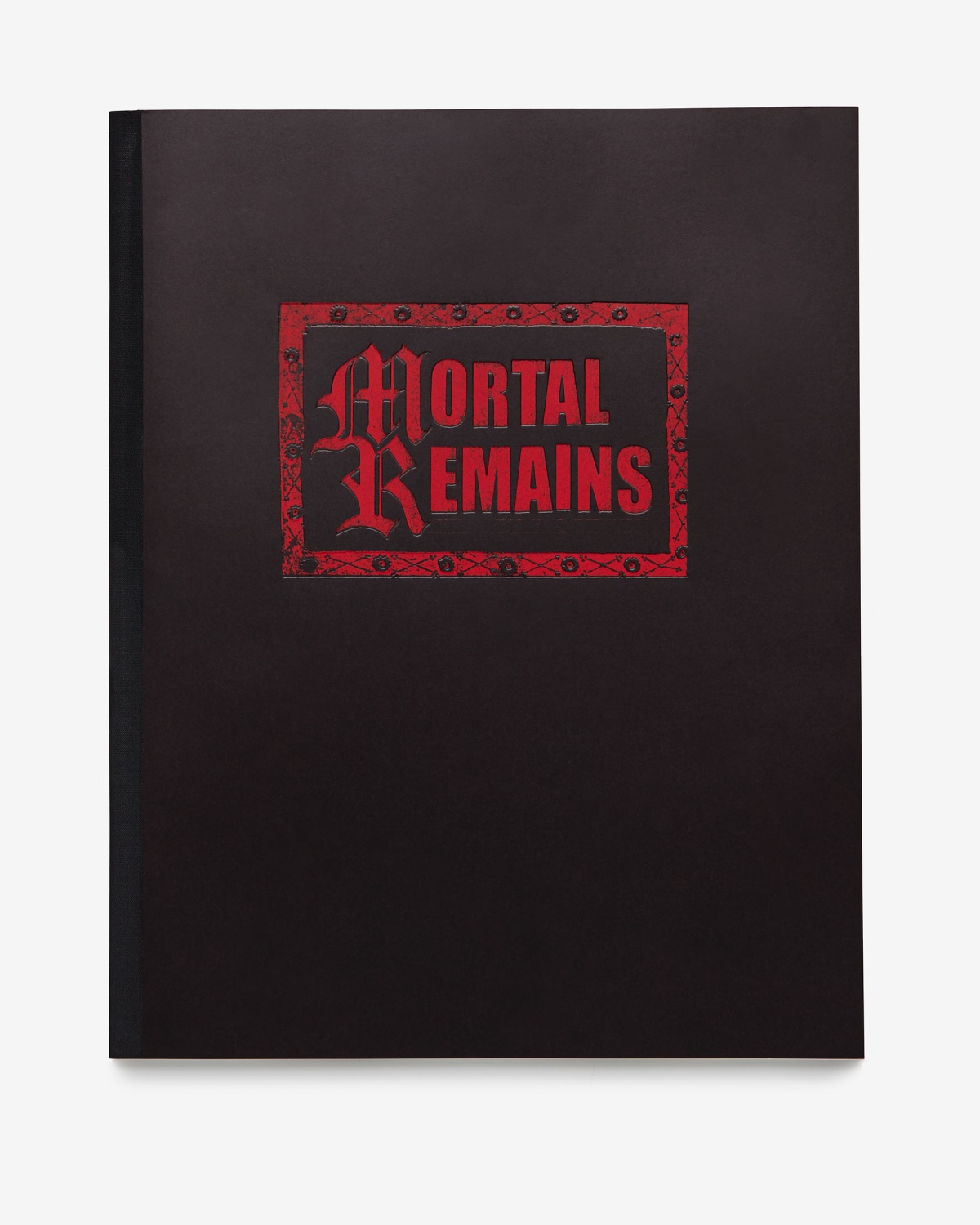

- “Mortal Remains” zine cover, art directed by Frances Wilks

- “Mortal Remains” zine interior, art directed by Frances Wilks

Frances’ background in graphic design gives her a structured approach to painting: She sees something she likes, she researches it extensively, and then she plans out exactly how she wants it to look on the canvas. But she notes that she sometimes wishes she had more freedom to her approach, jealous of the skillful, gestural style of artists like Francis Bacon. “He paints in a way that’s just so direct and impulsive, like you can see every movement. I’m always in awe of his portraits,” Frances says. “Maybe there’s a bit of envy to it because I always want to know how something’s going to look before I paint it, and it’s in my mind quite mapped out.”

For Frances painting is about looking within herself to identify emotion and reactions, things with deeper meaning and intrigue. Flipping through the pages of a book at home, viewing dance performances or exhibitions with friends in town, or, in the case of Saint Sebastian, browsing a gallery in Rome, Frances keeps herself open to new experiences that strike a chord to bring home to her working dining table in her flat’s sunny living room nook.

- Many books and her own works line the shelves of Frances’ living space. Photo by Lee Whittaker

- Frances’ boots sit beneath a secondhand Seconda chair by Mario Botta. Photo by Lee Whittaker

The table is covered in paints and supplies—at least she says it usually is, gesturing to a surface that is currently fully cleared—waiting for her next burst of inspiration to bring her to a seat. Working from home allows her to sit down at the dining table—where she never actually dines—whenever she feels like it. She says not having a dedicated space or time to paint relieves her of a certain pressure. “I have an idea and I just go and do it.”

Behind her on the sofa, I catch a movement. Frances is dog sitting for a friend who’s in New York right now. The dog, Gino, adjusts, circling a few times before laying back down on the sofa, clearly at peace in Frances’ space. Unlike her work, layered with darker meanings and infused with color, her home has a more light, minimalist feel. “I can be quite chaotic as a person, so I like things to be a bit ordered and clean and minimal so you don’t see too much chaos. Otherwise you’d go crazy.”

But, like her work, the objects in her space go beyond what you can see. Frances used to flip antiques and secondhand furniture as a sort of side project; the table where she works and its chairs were all pieces she purchased and ended up liking for her own space. The marble coffee table is another favorite she couldn’t give up. It’s true that they add up to a rather sleek and straightforward sum, but each piece has something a bit unique, a hint of character and history.

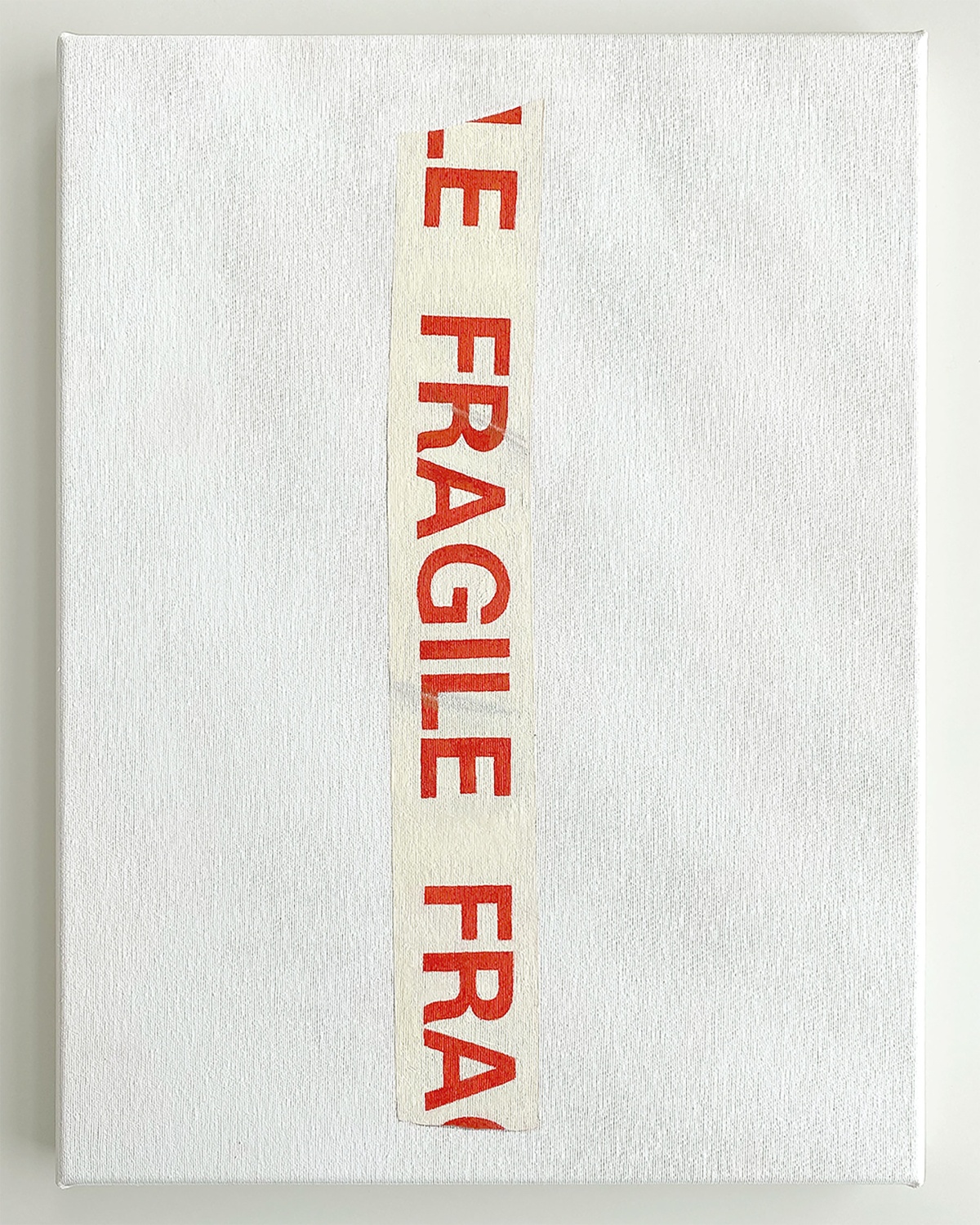

- Frances paints “FRAGILE” at her dining table. “It’s usually covered in paint and all sorts of crap. I never use it as a proper table because it’s destroyed.” Photo by Lee Whittaker

- “FRAGILE,” 2023. Artwork courtesy of Frances Wilks

Then there is the work itself, lining her shelves and hanging on the walls. Alongside the Marlboro sculptures and reinterpreted Saint Sebastian are several small, hyperreal paintings of everyday objects. Frances is in the middle of a new project, a series of trompe-l’œil works depicting objects like tape emblazoned with “FRAGILE,” running vertically down a canvas as if laid on top of it.

The trompe-l’œil paintings are a collection in progress, one she is looking forward to expanding with other, similarly charged objects. “I want to find more objects that maybe I can associate a different meaning to or something,” Frances says, reiterating the layers of visual interest and associated meanings in her work. “There’s a little element of it being personal, to kind of inject that into the work.”

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 11 with the title “Darkness with a Sweet Tooth.” Subscribe today.