Nipa Doshi and I are standing nine stories above street level, looking out from the balcony of her and husband Jonathan Levien’s home on central London’s protected Barbican Estate—a Brutalist residential complex and arts center designed by British architecture firm Chamberlin, Powell and Bon in the early 1960s. In the distance, against the overcast sky, looms a pair of glassy, modern apartment blocks. Mumbai-born Nipa jokingly tells me some friends of hers back home are bemused as to why she wouldn’t prefer to live in a similarly flashy building, but for her and Jonathan, purchasing a property in the Barbican was a no-brainer. “We used to often dream about having an apartment here; it felt so cosmopolitan, so London, and so chic,” she says. “It was like buying a piece of collectible design.”

The couple’s eponymous studio, Doshi Levien, has been in action for more than 20 years, creating everything from furnishings to fabric to an ice cream cake for Häagen-Dazs. They first turned heads in 2001 when they created a collection of pots and pans for French cookware brand Tefal and have collaborated with powerhouse brands like Moroso, Hay, Kettal, Arper, B&B Italia, and Kvadrat, all of which are drawn to Doshi Levien’s idiosyncratic way of working. “Nipa and Jonathan are deeply rooted in their culture and at the same time present in the contemporary now,” says Stine Find Osther, vice president of design at Kvadrat. “Their handwriting in the world of design is extremely unique and easily recognizable.”

- Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

- Doshi Levien’s Earth to Sky lighting sculpture sits beneath an artwork commissioned from Indian artist Shammi Bannu. Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

Nipa and Jonathan settled in their three-level Barbican apartment in 2017, having previously lived in a duplex flat on the estate. Prior to that they’d been residents of East London’s characterful Spitalfields neighborhood, occupying a warehouse that dated back to the 1850s. The two-floor industrial space had conveniently allowed them to live upstairs and run the studio from downstairs, but when Nipa fell pregnant it was immediately clear that it wouldn’t be an ideal setting for raising a child. The couple resolved to separate the personal and professional spheres of their lives; the studio was relocated to a former furniture workshop on Columbia Road (known amongst Londoners for its charming flower market), and the Barbican Estate became home. “We decided on the Barbican because, contrary to the warehouse, it was designed for living,” Jonathan says. “There’s such intelligence to the layout of the apartments.”

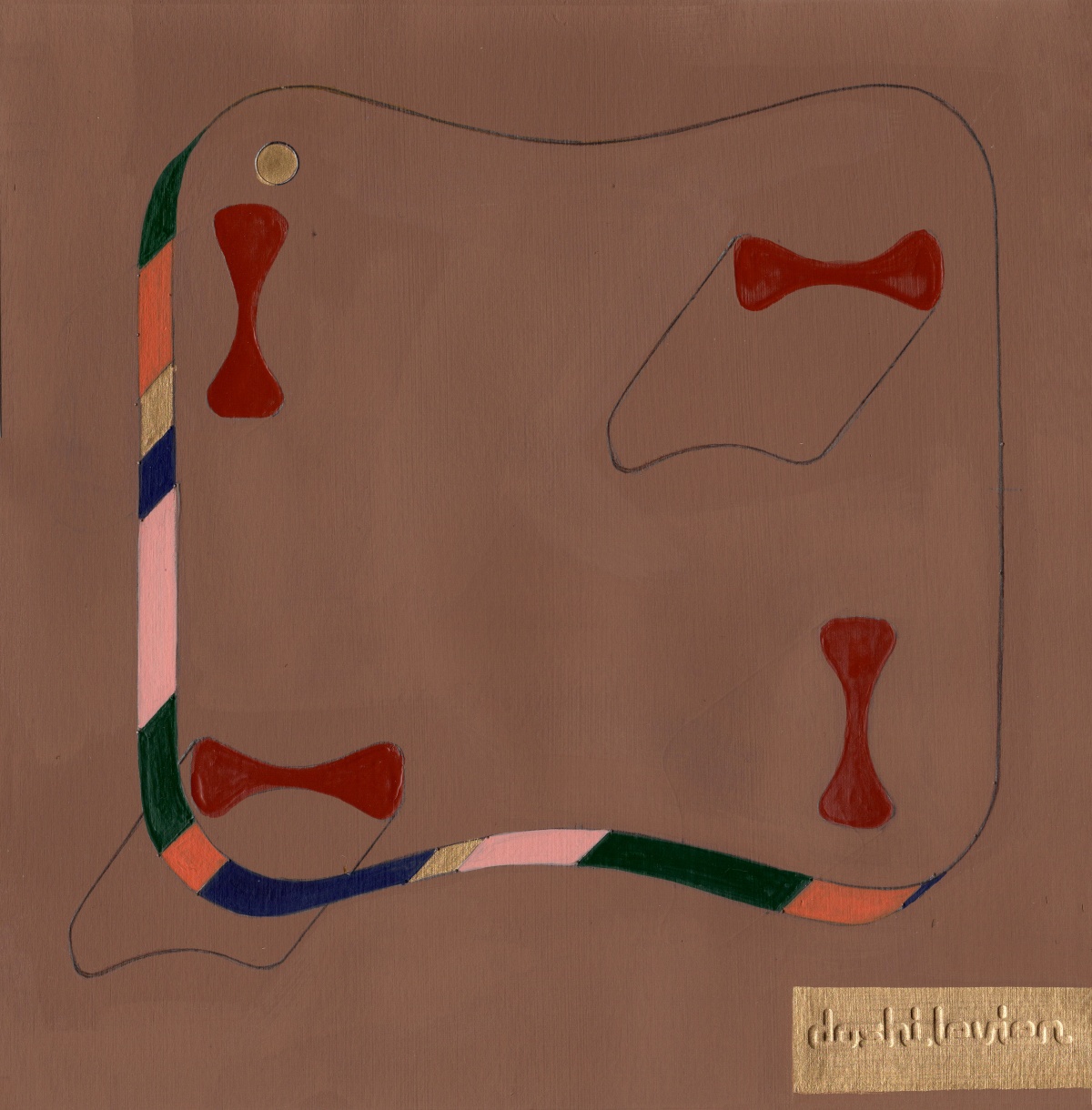

- Kinari for Galerie Kreo

- Kinari for Galerie Kreo

Thanks to her upbringing in India (and spending time in her aunt’s embroidery workshop in Ahmedabad), Nipa has a deep-rooted love of craftsmanship and vivid color. Jonathan, meanwhile, is obsessed with materiality and process; he whiled away much of his childhood in his family’s toy factory in Scotland, tinkering to see how things are made. He also completed training in cabinet-making.

When it came to designing their apartment the two had to merge their markedly different interests and tastes. They let the furniture do the talking. “We really needed a canvas against which our pieces would shine,” Jonathan says. “The apartment wasn’t designed; it evolved.”

- On the stove, Nipa and Jonathan’s cookware for Tefal. Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

- Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

In the kitchen unsightly wood-laminate cupboards installed by the previous owner have been replaced by clean white cabinetry and walls to match. The focal points of the space are now a colorful mirror the couple created for Galerie Kreo and a sculptural side lamp from Doshi Levien’s Earth to Sky range. You’ll also find many trinkets gathered from the couple’s far-flung travels and some black-and-white images by Sooni Taraporevala, a photographer who captures day-to-day moments of life in India. “I feel like you can’t apply an interior to a space. I prefer when the objects create the interior,” Nipa says. “That’s why the apartment feels very eclectic—because these are all pieces we’ve accumulated over time, and love. There isn’t one style.”

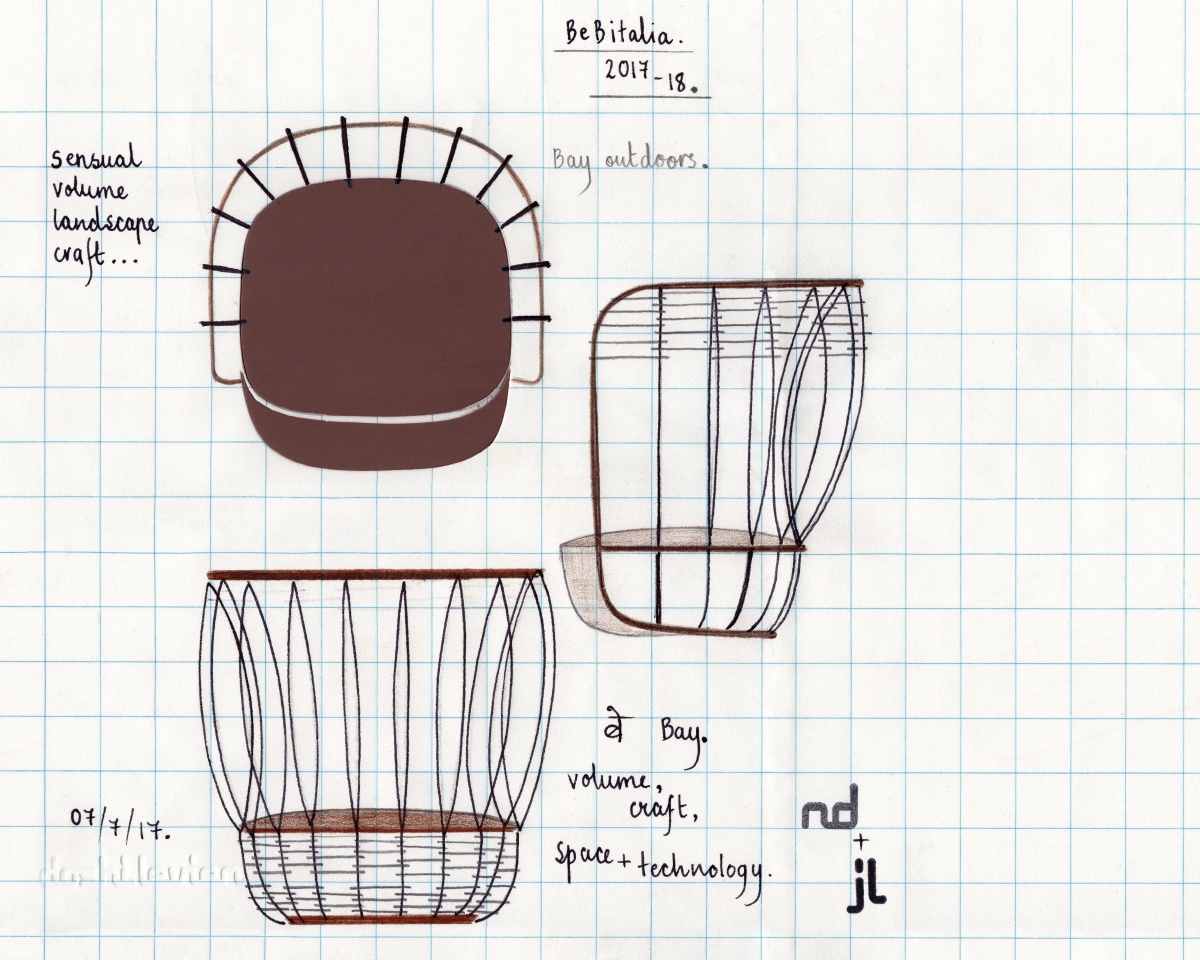

- Bay for B&B Italia

White walls continue into the adjacent living room, which features heavy hitting design pieces like Le Corbusier’s slender Parliament floor lamp (originally made in 1963 for the Palace of Assembly in Chandigarh, India) and a black leather edition of Herman Miller’s Marshmallow sofa. There’s also more of Nipa and Jonathan’s own designs, including another Galerie Kreo mirror (this one with tinted, candy-colored glass), a patterned daybed from their Charpoy collection with Moroso, and a turquoise blue version of the wide-backed Capo armchair the couple created for Cappellini. It has two deep-set armrests that, when I visit, are cradling books; Jonathan warmly recalls when his son Rahul (now 14) was a small child, how he’d sit on the arms as stories were read to him. “That’s why I’ve got a soft spot for that piece, the memories that come with it and its unexpected functionality we discovered,” he says.

- Mirror for Galerie Kreo and Charpoy for Moroso. Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

- Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

Nipa finds it tricky to single-out a favorite item in the house but is particularly fond of a painting they commissioned by the seventh-generation Indian miniature artist Shammi Bannu. The whimsical work depicts the Hindu god Krishna and his consort, Radha, on the grounds of Villa Sarabhai, a modernist, Corbusier-designed home in Ahmedabad that Nipa has always loved visiting. Look close enough and you’ll see a couple of Nipa’s and Jonathan’s furnishings, too, which have been discretely dotted through the image like Easter eggs. “The painting reflects my idea of utopia, where you have that plurality of influences, culture, and architecture,” Nipa says.

Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

It seems the only challenge presented by the apartment is trying to communicate between floors; although the interior is largely open, the pod-like, self-contained rooms can make it tricky to hear. “We started off going to speak to each other on the same level, but now we just yell,” Jonathan laughs. “I think we must have a reputation for being the noisiest family in the block. Plus I’ve started playing the saxophone.”

In between the fanciful furnishings and bespoke artworks I spot a modestly framed photo of Nipa and Jonathan. It’s from a photoshoot the couple did in 2007 for another magazine, after they were named breakthrough designers of the year. The merit came 12 years after the two met as students at London’s prestigious Royal College of Art, bonding over a shared desire to rattle the status quo of the design sphere. “At the time industrial design was very masculine, very focused on problem solving and almost quite restrictive,” Nipa says. “I’d grown up in a place where there was a material culture, a sense of ritual, and a consideration for what is beautiful, while Jonathan had come from an incredible making background … We both wanted what the other had. And then of course we fell in love.”

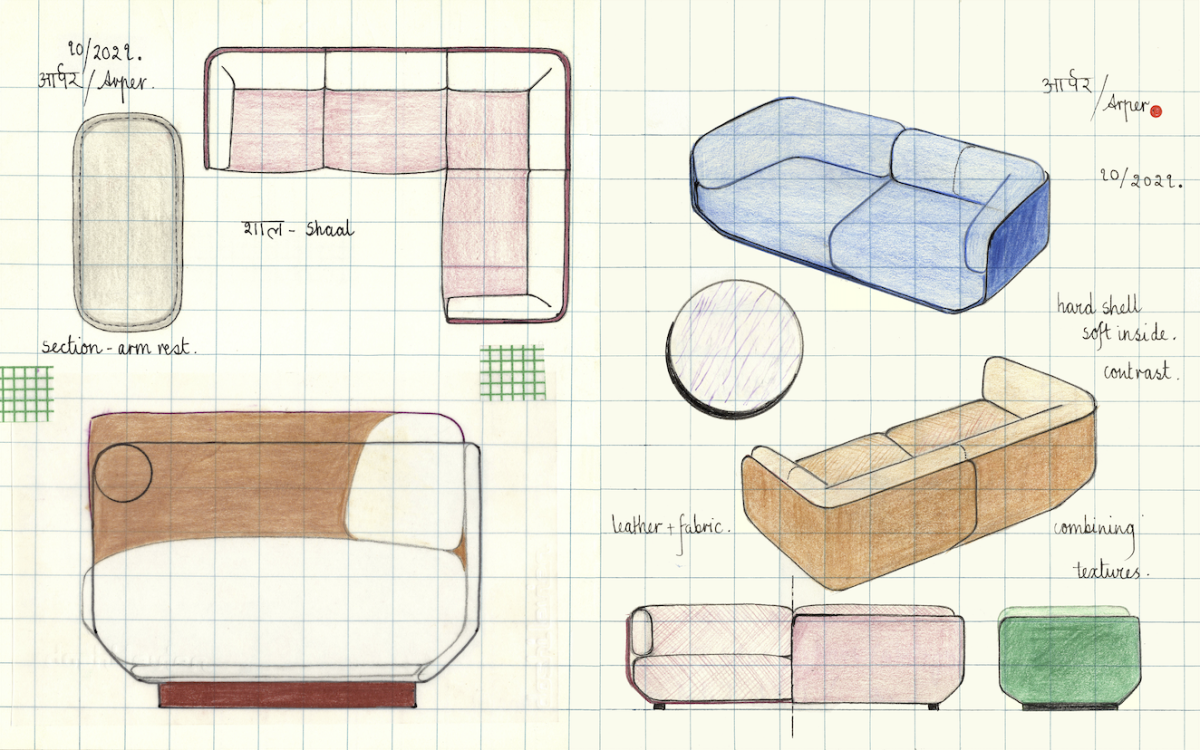

- Shaal for Arper

Even as their friendship blossomed into something more, the pair remained unflinchingly honest when critiquing each other’s work and ideas. “It’s not easy to take all the time, but underneath you know it’s coming from a position of respect and wanting the best for the project,” Jonathan says. “With that understanding you can be very straight with each other.”

- Rabari for Nanimarquina cushions the floor of Nipa and Jonathan’s living room. Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

- Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

My tour of Nipa and Jonathan’s home culminates in their third-floor bedroom, which is fronted by a huge arched window that overlooks the angular Cromwell Tower—one of three high-rises on the Barbican Estate. Finding calm in the room’s airy, temple-like proportions, Nipa tells me she’ll often retreat here to meditate and gaze at the surrounding concrete landscape. The room also has a graphic, hand-embroidered rug from Nanimarquina and Doshi Levien’s Rabari collection, plus a bed frame the couple designed to their preferred scale. “Rather than big landscape furniture, we like things that have air around them, things that are sculptural and can be encountered from the back or the front,” Nipa says.

A door in the corner of the bedroom opens onto a small terrace dotted with pots of home-grown herbs and spindly plants. Given that we’re barely out of the freezing London winter, the outdoor area looks optimistically verdant, but Jonathan confides he’s disappointed with his gardening attempts so far. Going forward he plans to grow different grasses that are easier to maintain.

- Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

- Photo by Jonas Lindstroem

So what’s coming up career-wise for Doshi Levien? In January 2023 the pair was given perhaps their highest accolade yet: a place on The King’s 2023 New Year Honours List and a Member of the Order of the British Empire award for their services to design. Nipa says the recognition feels particularly potent as someone who was born outside of the UK. “It was quite emotional for me, although I didn’t expect it to be,” she says. “There’s this whole question of identity, where you belong, what is your culture, and does your voice matter … For me the award meant acceptance and recognition for merit.”

The duo is now setting up a color lab at their Columbia Road studio, which will include a custom shade system and an archive of palettes they’ve previously created for clients. There’s also another fabric collection in the works with Danish textile company Kvadrat and plans to take on more commissions from private collectors—a liberating experience the couple says allows them to be “maximum Doshi Levien.” “When you first start your studio you have one client, and all your ideas go to that one client, and each idea is laden with maybe four other concepts that should be separated,’ Jonathan says. “We’re at a place now where we’re able to channel those ideas in the right way.”

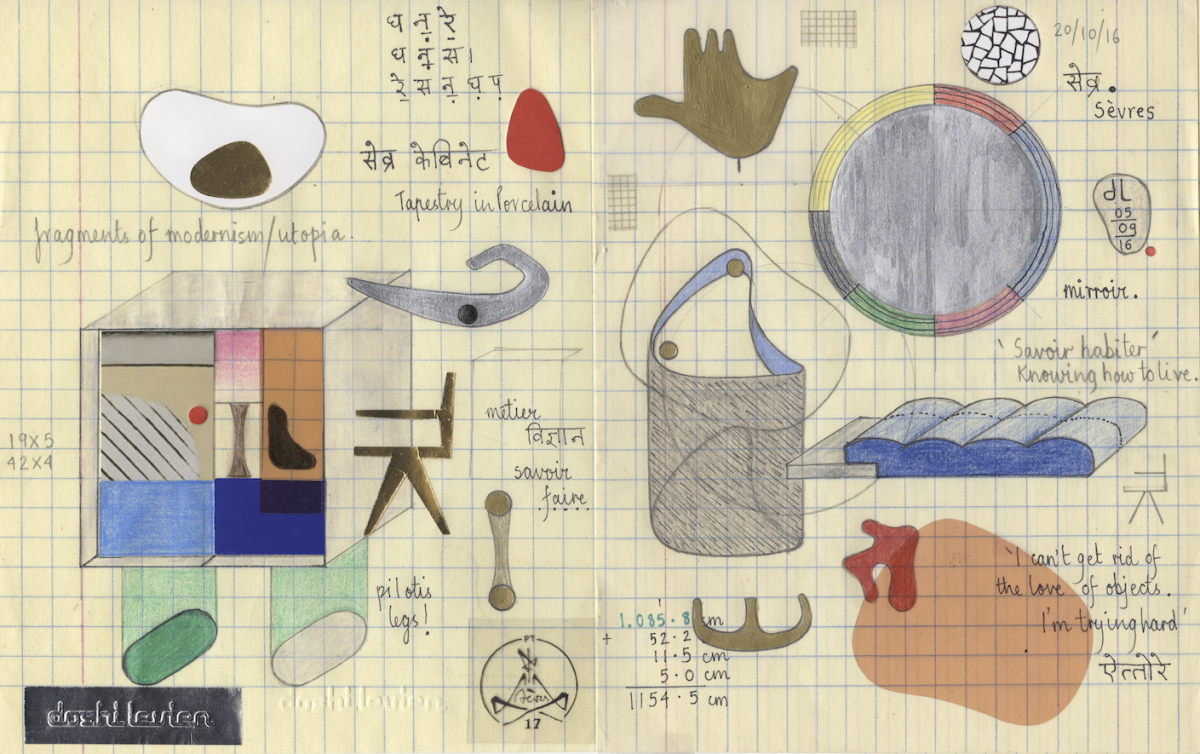

- “Le Cabinet” by Doshi Levien and Manufacture de Sevres

When it comes to choosing their next collaborators there are loose criteria. “If companies have a liveliness and lightness it works really well,” Jonathan says. “It sounds frivolous, but I want to have fun doing what I’m doing. I don’t want things to be too serious.”

Maybe the most important thing is that the couple and their clients aren’t completely alike; contrasting aesthetic approaches is, after all, what has made their studio—and the design of their Barbican home—such a success. “I wouldn’t work with somebody who’s exactly like me. It wouldn’t make any sense,” Nipa says. “Our work is what it is because we’re bringing together different worlds.”