“This isn’t where I do the messy stuff,” Daniel Widrig says as he wanders through his studio, a stone’s throw from Hackney Wick train station in east London.

The stark workspace is limited to an oversized wooden table, a couple of leather sofas, and a floor-to-ceiling FDM printer that hums quietly behind a curtained cupboard. A handful of Daniel’s own works—like his 2020 work “Undressed,” reminiscent of a jumble of bones made in PLA and sand, and his 2009 “Brazil,” a limited-edition armchair made in CNC-cut plywood—are represented gallery style at the edges of the studio’s front room, set against slightly weathered, white-painted walls.

“It’s such an old building that it’s almost pointless to try to fix it up perfectly,” he says. “Some days there’ll be a water leak or something like that, but otherwise it’s a nice space. It’s a bit like an old ship; sometimes you just have to paint over the cracks.”

- The SnP Chair. Photo by Naaro

- Daniel’s “SnP” collection is made from interlocking parts of injection-molded recycled plastic. Photo by Naaro

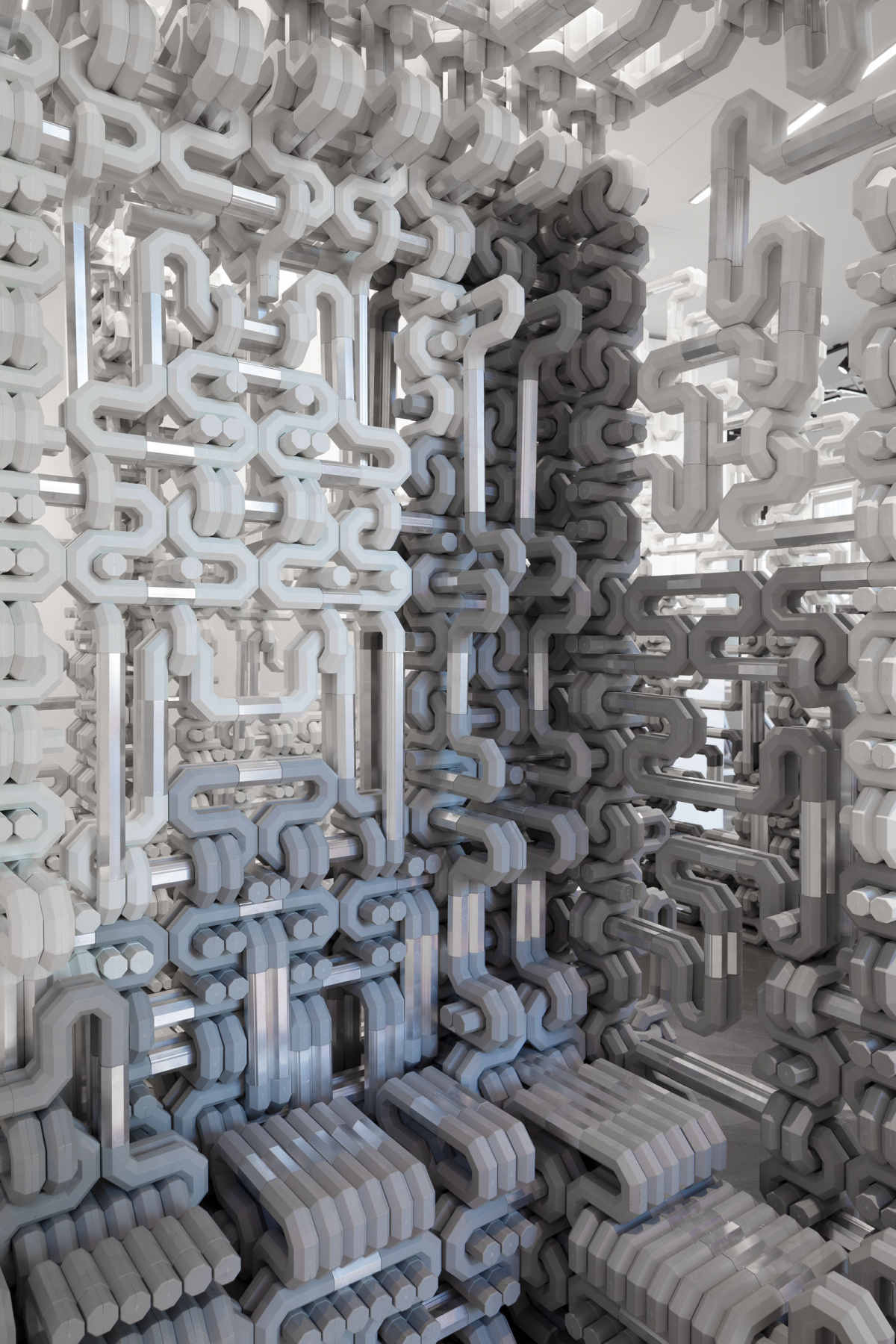

Daniel has built a multidisciplinary body of work that includes fashion, architecture, art, and furniture projects. He is especially celebrated for his advanced use of materials and technology. Some of his works, like the “SnP” chair, are made from interlocking parts of injection-molded recycled plastic. Other pieces, like his amorphous “Instances” sculpture, are 3D-printed from sand.

Tucked near the rear corner of Daniel’s studio is a pair of widescreen computer desktops, where almost all of his ideas begin. “My creative process is very similar; whether it’s an art, architecture, or design project, most of it starts with digital experimentation,” he says. “I’m always trying to be as playful as I can.”

Daniel’s easygoing approach means he isn’t afraid of the trials and errors that come with creating something new. “I’m not very good at finishing things, but I’m very good at starting,” he muses. “It happens quite often; I do something, then I don’t like it, put it away, and after a while I might start to like it again or develop it further.”

“Instances,” 2019. Photo by Daniel Widrig

Before he settled into his current apartment, Daniel lived full-time at the studio. Now all that remains of that domesticity is a modest kitchenette and a small fridge sparingly stocked with drinks and snacks. “If it’s really busy I’ll crash here and won’t leave for a few days,” he says. “I mainly work alone. I’m a bit of a hermit in my work life. Sometimes I like to shut everything else out … so the studio is more like my little cave.”

When Daniel needs to work on big, “messier” pieces, he hops on the train from London to Lacey Green in rural Buckinghamshire. There lies Grymsdyke Farm, where students and practitioners of architecture, art, and design can explore materials and methods of making. It was established by architect Dr. Guan Lee, whom Daniel met while teaching at University College London’s prestigious Bartlett School of Architecture, and later went on to set up a research facility dedicated to seeking new ways digital fabrication techniques can be applied to everyday matters.

Across the grounds of Grymsdyke, old barns have been converted into workshops where Daniel has the freedom to do everything from CNC cutting to sandblasting. The designer has long cherished the farm’s facilities but, particularly during the UK’s national Covid lockdown, he grew to love the bucolic landscape.

3D printing is a favorite tool of designer Daniel Widrig, who’s also used it to create a series of intricate, skeleton-like garments for Dutch haute couturier Iris van Herpen. Daniel graduated from the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London and founded his practice in 2009. Photo by Naaro

“I started to not be so sure about living in the city, but maybe that’s just an age thing,” he says. “Until recently I really enjoyed all the buzz of Hackney, but it can get really crazy on weekends … Sometimes I wonder if I should stay in the countryside and just come to London every now and then. I like the city, going to exhibitions, cycling around, and it’s beautiful to bump into people and socialize, but health-wise I think it’s probably better to not be here 24-7.”

For now Daniel will stay firmly in Hackney Wick, finishing up his 2021 projects. Before year’s end the designer is set to unveil a new public artwork near Dresden that comprises four huge bodies of metal, each dripping with water. Due to the piece’s location and ongoing travel complications brought about by the pandemic, much of Daniel’s input has been carried out remotely, but the designer appreciates that the creative industries have become slightly less hectic. “I’m not somebody who is too keen on big design shows and busy travel schedules. I’ve always tried to focus on my work and avoid all the noise,” he says. “I think it’s important for everyone to reflect.”

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 07 with the headline “Daniel Widrig.” Subscribe today.