It’s sunny, low 70s, in the Del Rey neighborhood of West Los Angeles. A new office compound is under construction—one of many new developments aimed at making room for the tech, startup, and media companies that are flocking to the area, what’s being referred to as “Silicon Beach.” The office, so new the light switches are being installed as I visit, looks like many others in the area, with skylights, open floor plans, and glass-walled conference rooms. But there a few key differences, one of which is that their Chief Design Officer Daniel Simon parks his car, a stunning 2006 Ford GT in Centennial White, inside the office, just in front of his office door.

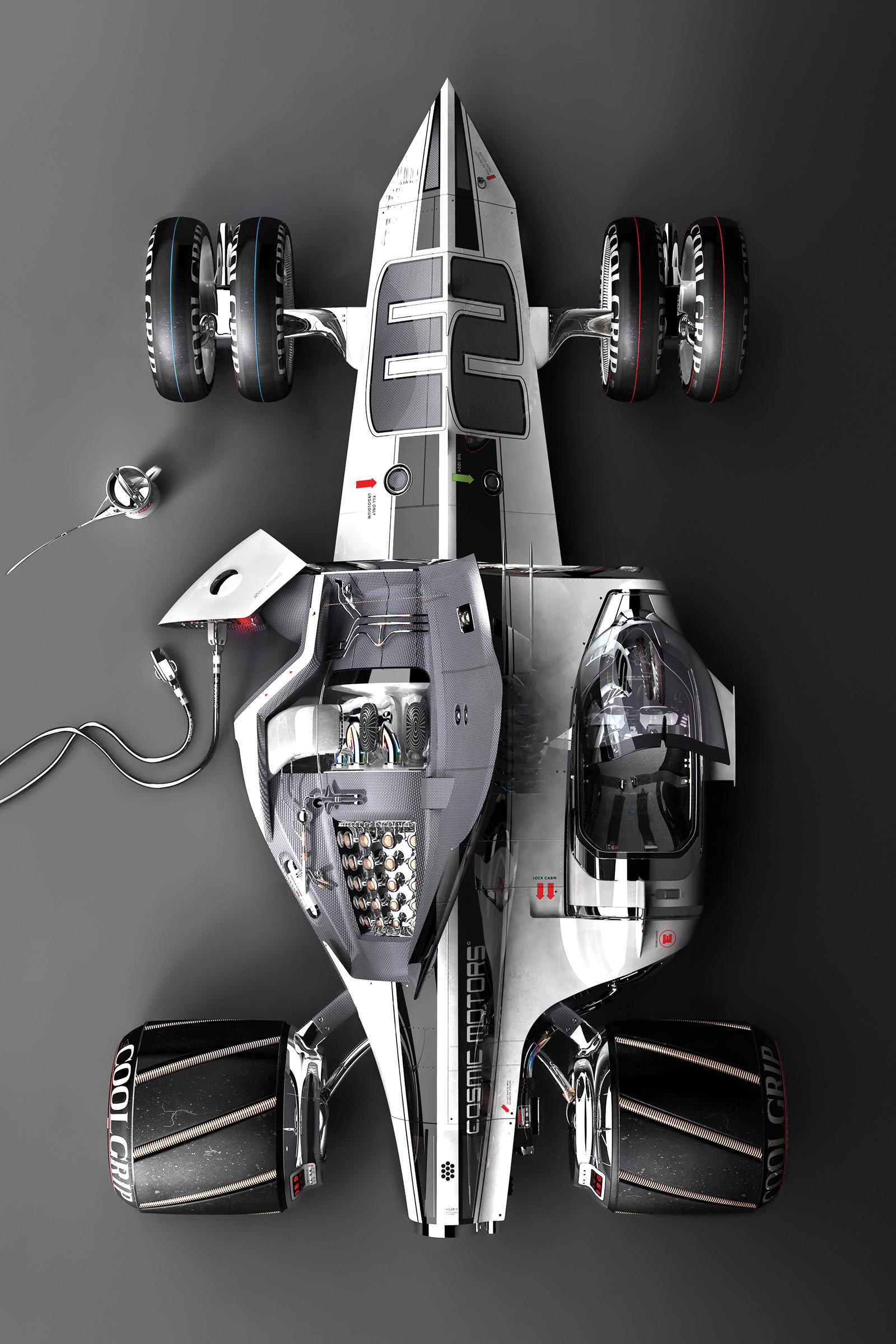

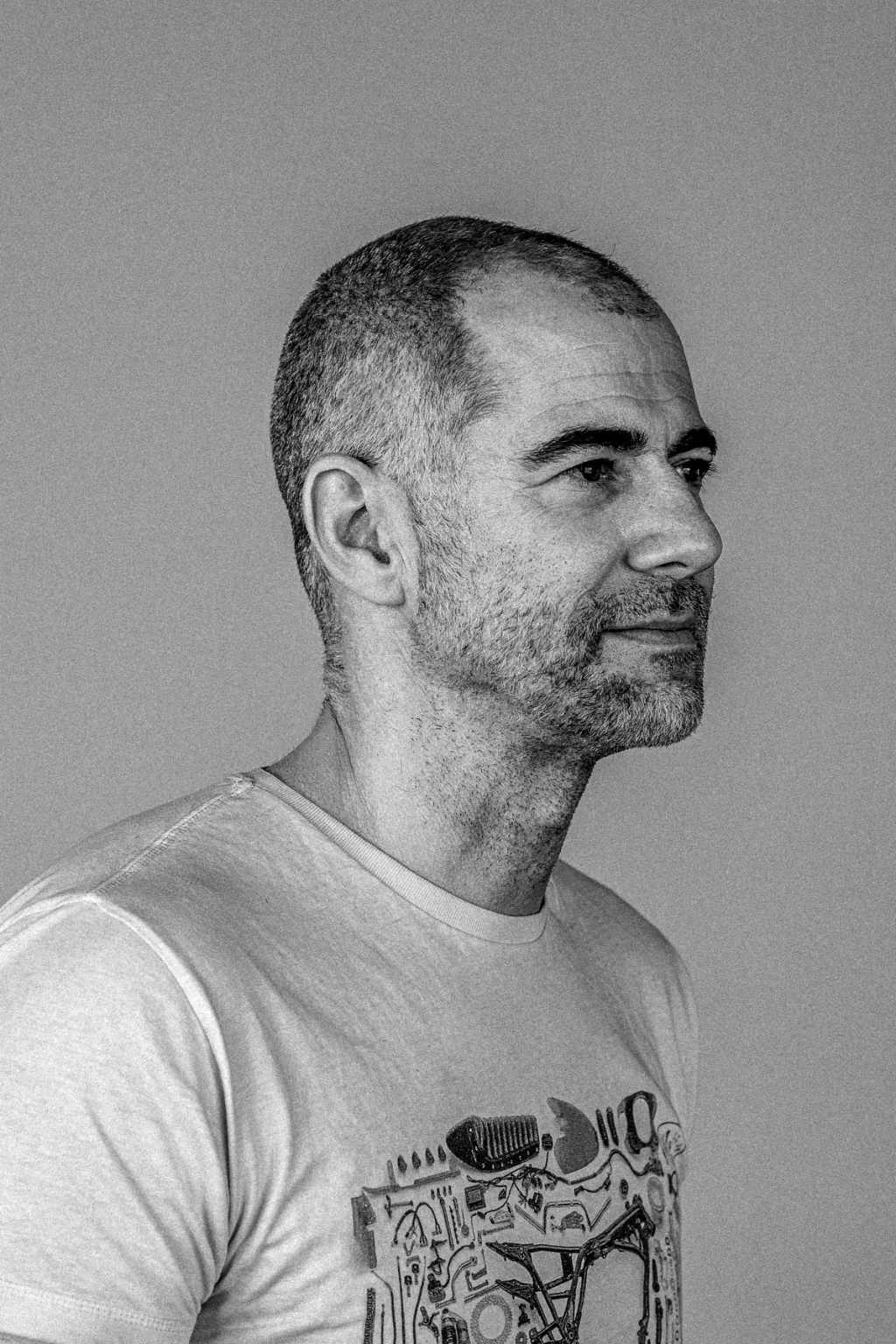

The second key difference is the corner office is not dedicated to an executive but to a driverless robotic car. This is the Roborace US headquarters, a startup competition between autonomously driving electric vehicles designed by Daniel Simon. Daniel, who is now 44 and grew up in Germany, is likely best known as the vehicle concept designer for Tron: Legacy, Captain America: The First Avenger, and the sci-fi film Oblivion. But to car designers and fanatics he’s known for something else: the seminal concept car book Cosmic Motors (2007). I spoke with Daniel about his path to Roborace and his vision for the future of automotive design.

Daniel Simon’s 2006 Ford GT parked in the Roborace US headquarters. Photo by Chris Force

Where are we and what are you doing here?

This is Roborace headquarters; we’ve only had this space for six months, so we’re still growing with a few desks to fill. So far Roborace has only been in the UK, but we want to be way more dominant in the US. The last decade I’ve largely worked from my home office. I’ve moved three times—the most memorable was up north in wine country, just looking at vineyards and horses. But it turned out to be more like a magazine cover than a reality. With the stuff I do, dealing with cutting edge technology, just looking at horses was a little limiting at times. This location is fantastic, though.

In Daniel Simon’s second book, “The Timeless Racer,” main character Vic Cooper travels to 2027 and witnesses the fictitious Prideux-Martin MF27 racing car, above, in action.

Was it Hollywood that brought you out here?

Yes. I was happily living in Berlin consulting for Bugatti. I’d made my way out of Volkswagen in 2006. I was craving more of a creative outlet than cars. I love cars, but designing the next generation automobile was limiting for me. I was surrounded by designers who knew how to do that really well. It was extremely creative, and while creativity does needs boundaries—otherwise you’re lost in the conversation between design and art—for me those boundaries were too narrow. Others could thrive in them, but I couldn’t.

I kept in touch with Bugatti and kept consulting from my Berlin apartment. My book Cosmic Motors came out at that time as well. I pretty much created the book in two years, and it opened more doors than expected. This was before the iPhone and Instagram. Ironically I got the attention of the book publisher through a website, but I was probably one of the first corporate car designers who had his own site, which got me into some trouble. Back then the thought was, “We invested in you to work for us, so don’t use a megaphone and broadcast, ‘Here I am. Here’s my email address. Contact me.’” That’s changed now.

- The Galaxion 5000 coupe from “Cosmic Motors.”

- The Gravion from “Cosmic Motors.”

In 2007 Cosmic Motors was found by a Hollywood director. I’d only been to the US once before, in 1997, so it was interesting when I got this email from Joe Kosinski. It was super short; he was probably very busy and saw my book and just wrote me, “Your aesthetics fit my vision for this film I’m doing called Tron.” I wasn’t a crazy movie buff, but it was a fascinating opportunity for what I could do from a design perspective.

But there was so much paperwork involved. I’m German, so it wasn’t that easy for me to come over. It took awhile, almost six months. I started tinkering with a Plan B and opened my own design studio in Berlin. Literally the day I went to get the key the papers came through and within a week I was here. Disney and the director were tremendously helpful in getting me here and I never left. That opportunity was brought to me, but I probably paved the way with my book. But I wasn’t actively looking to get into the movie world.

“Designing for the future gives me comfort because I’m freaked out about it,” Daniel Simon says. Photo by Chris Force

It seems like your career has evolved from project to project, while they’re all somewhat independent. Is that how things happened for you?

It’s important to see it in a geographical context. I’m coming from Germany where things are relatively affordable compared to LA. I worked in Spain also. I was able to create financial stability in my first years. I didn’t have any student loans, college was cheap—pretty much free. I joined Volkswagen, I watched my lifestyle and I made a pretty good living working on my own dreams. Versus say coming from a US college with steep debt and having to say, “I need this job!” There’s a panic attached to that system that doesn’t work with the nonchalant, “Let’s do what’s cool and see what comes of it.” I had that luxury, and I’m a result of a different system.

Related | Christian Von Koenigsegg Keeps Chasing His Dreams

Even when I came into the US there was no need for me to pay off a house. I didn’t have a family or kids (my daughter is 3 now). It was a luxury to pick things I like and approach people I dreamt of working with. And let’s be honest, something like Tron is so powerful that to this day it gets me into some doors.

Logistically I needed to find another film project because I wanted to stay part of the film world. I also needed to stay on my visa. I jumped onto Captain America. What’s beautiful about something like Captain America is designing something for the past, and to sit there with the director Joe Johnston and wonder how would an alternative future be thought of 60 years ago? After that I started Daniel Simon LLC. At that time the whole electrification of transportation started to pick up, especially in California. LA became a hot spot for electric startups and the flying car industry. It’s a wonderful area for designers like me to be.

The Lotus C-01 is considered by some to be the most beautiful super bike ever created.

Does a personal project have to make you money?

Back in Germany it didn’t, but coming to California has transformed me. I like the handshake philosophy that exists here. Germany is extraordinarily bureaucratic in terms of doing tax returns and business reports. I also worked in Japan for awhile, and they even raise this process. Then I came to the US and started doing big figure deals with a handshake. I thought that was fascinating.

Would you move back to Berlin?

In the US if there’s a startup next door it might become a global phenomenon. If there’s a startup next to you in Berlin it might become a domestic phenomenon. I generalize here, but I’m pretty confident in the statistics. Things are bigger here, and I like that. I’m totally aware of the shift toward Asia, especially in China. Working with Roborace we’re sensitive to what’s happening globally. Also let’s be honest, the weather is a big factor; just being able to pull your car out any Sunday.

“Designing things people have done before but just with little changes feels useless to me,” Daniel Simon says. “We’re here to initiate change and leave our mark. ” Photo by Chris Force

Was there a time where you felt like things really clicked for you?

I sometimes wish back to romantic times when I was sitting in Brazil with no internet and determined to design this aircraft just because it made me happy. Now it’s 2020, I wake up and have seven apps to check with clients before breakfast. I’m on Instagram; I see fantastic artwork every day and it sidetracks me.

I grew up in communism until I was 14. I saw the rise of computers. I did my first car drawing on the Commodore 64, working for days to get the headlights in. Then PCs came out that could produce more than 16 colors. But they are never fast enough. The crux is if you give me 10 hours and my technology can allow me to do it in two hours, I’ll still explore and by the 11th hour be exhausted and frustrated. Technology is not a limit; it’s always our expectations.

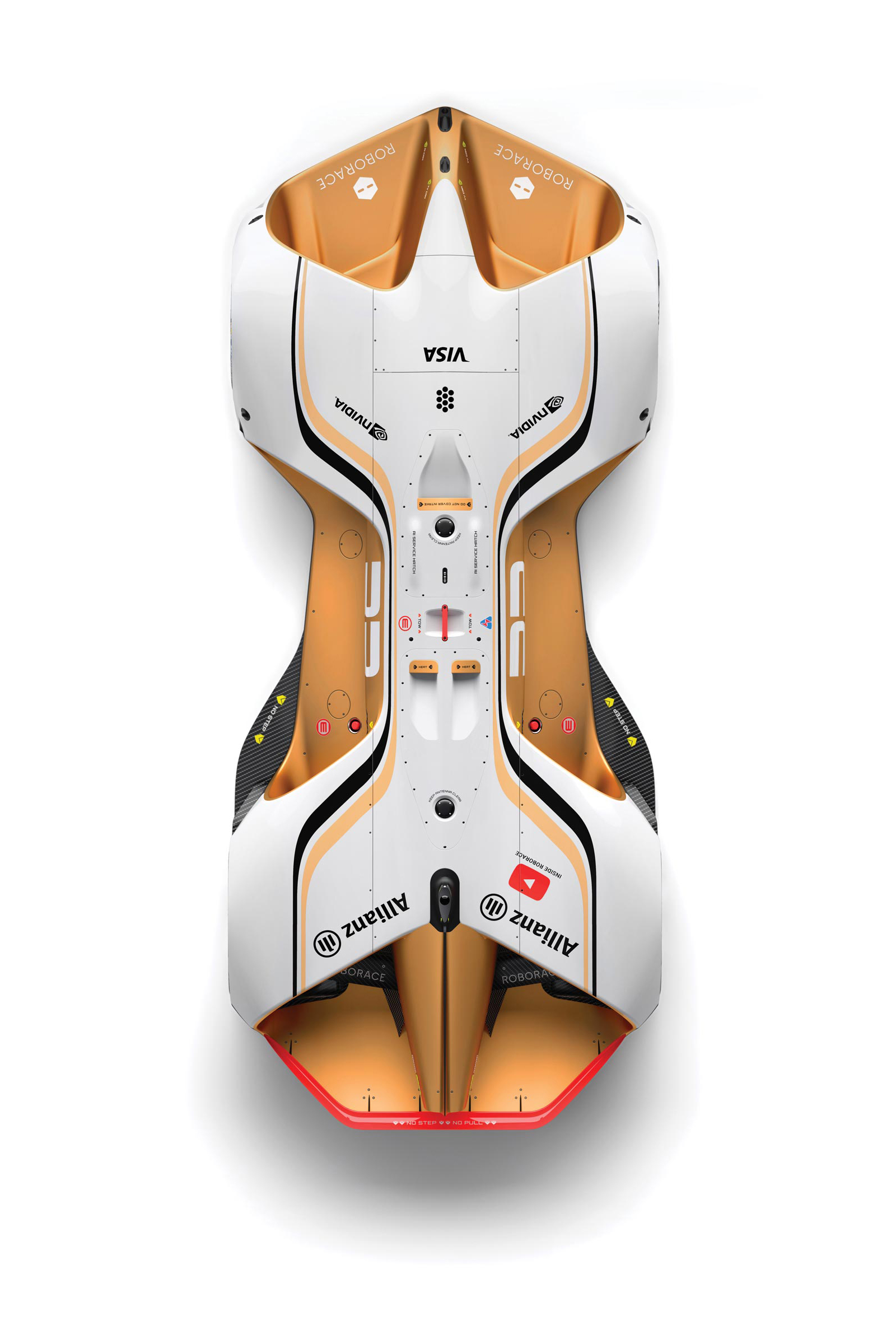

- The Robocar from Roborace.

- Roborace’s DevBot 2.0 is all-electric and can be driven by a human or AI driver.

Tell me about Roborace.

I’m chief design officer. We deal mostly with cars so I’m responsible for the look and feel of our vehicles, but I also advise on the looks of everything else. I was one of the first hires. I met the founder Denis Sverdlov, a successful London businessman, at CES and within minutes we drafted this whole idea. He had the concept from a business, but we drafted what the car should look like.

Denis is a fascinating person. He has fantastic energy; he’s the man behind all of this and I’m very grateful to have met him. Roborace is the perfect synergy of what I love. It’s future stuff and cars without being cars. It’s pretty much Cosmic Motors brought to life.

Designing for the future gives me comfort because I’m freaked out about it. There’s a lot to come. I would rather be in the know than wake up and say, “Now company X is turning my lights up and down depending on my skin temperature.” We are still in the driver’s seat to design the future.

The Roborace office isn’t like other offices: Motorcycles and cars are just as common as desks, pens, and other office staples. Photo by Chris Force

What does the day to day look like in designing the future?

Let me start with Roborace. If the future of transportation is partially or fully autonomous, you’ll have a market and competitors. How can they show who is best? The old-school way is magazines, websites, or YouTube. But how will autonomous driving behavior be compared? There’s not just one type of autonomous car. One way to show who is best is through competition. We want to build a platform like Formula 1 was back in the day for McLaren, Mercedes, or Ferrari. Formula 1 is at a crossroads now where they are becoming irrelevant. Formula E stepped in, but it’s still a championship of drivers. We know a lot about it since Lucas di Grassi works with us; he’s a former Formula E champion. But I think we’ll need a competition where different AIs can compete. What you have is a championship of AIs with no drivers in the cars. I don’t like the word driverless because there is still a driver there—it’s just not flesh and bones.

How are the races coming along?

We are in our second season. Our teams are mostly universities. You have The Technical University of Munich (TUM), University of Pisa, Graz University of Technology, and Arrival, which is a British company. They bring in the software. In extremely simplified terms they come with a USB stick. The car is waiting, and they put the brain in it. We want to be a competition of software: Who writes the better code to take a turn at the perfect speed when the corner is wet? This is what will be important for road safety. Looking to the future, I don’t see the cars being the perfect model for what we do because they have a cockpit. My job now is to design the next car.

“I love classic cars. I can probably name all of the classic car designers,” Daniel Simon says. Photo by Chris Force

Your design role sounds like it also has a lot of strategy, figuring out how this will work in the marketplace.

Absolutely. Doing that in a (traditional) car company bored me to death. “Will this station wagon attract…” I always thought the strategy boards were the same. It’s always the “dynamic active lifestyle.” I’m not making fun of it, it’s just an observation. It’s hard to sell cars. The market is so big and there are so many players. But these strategic thoughts are much more fun for me here. I love to do stuff I haven’t seen before.

Designing things people have done before but just with little changes feels useless to me. Just getting a paycheck, paying rent, and eventually dying. We’re here to initiate change and leave our mark. Yes, you could also argue, “Is autonomous car racing doing anything good for society?” I really think road safety could increase dramatically with autonomous cars. It’s not going to happen tomorrow. But people are driving like maniacs right now. Everyone is on their phones.

The argument from the public is, “You’re taking the driving joy away.” Absolutely not. It will make things better. If I see people racing from traffic light to traffic light and think that’s driving passion, they have not been on the track. Imagine a fully autonomous car. It sounds boring, but you pretty much have the brain of (Ayrton) Senna in your car or Michael Schumacher (both champion Formula 1 drivers). How amazing is that? You can turn him on or off. Imagine you have a new Porsche 911 and it comes with the XYZ fully autonomous feature. Most of the innovations today are driven by government regulations so maybe cars have to be autonomous in some situations. There’s no reason to cry because you can put a button in there where you can dial it to zero. It’s Sunday, you can take your Porsche to the track, buckle in, dial in your driver Le Mans winner Tom Kristensen, and see how he takes the turns. It will make how we learn driving now look ridiculous.

How does the big picture boil down into your ordinary process of coming into the office every day?

Things are still made of nuts and bolts. It’s still a car with four wheels. There’s still a gearbox and a shell that goes over it. As philosophical as it all sounds I still have to design a car. Maybe in 20 years that skin can move and breath. But it’s stills sculpting, there’s feeling in it. Does this look too round, too masculine, too shy? That’s where I want to move Roborace.

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2020 issue of Sixtysix with the headline “Daniel Simon.” Subscribe today.

Photos Courtesy of Daniel Simon