“Coming from a large family, art was the first time I’d received real affirmation for anything I’d done,” the artist Dan Walsh tells me inside Paula Cooper Gallery in New York City. “It was meaningful, and it made me get serious about my art.”

Dan’s demeanor is a blend of matter-of-fact and easygoing. He leads me through the gallery with the confidence of an owner. And it makes sense—he’s been exhibiting with Paula Cooper since the ’90s. Their relationship began when an art director from the gallery sought another participant for a show featuring artist Rudolf Stingel. Once Dan’s paintings were presented to ownership as an option, he was immediately in the running.

“Paula visited my studio the next day,” Dan tells me. “We went through my paintings and slides, and she gave my work a thorough review. The next day she bought one of my paintings—and just like that, I was in the show. It was a huge stroke of luck.”

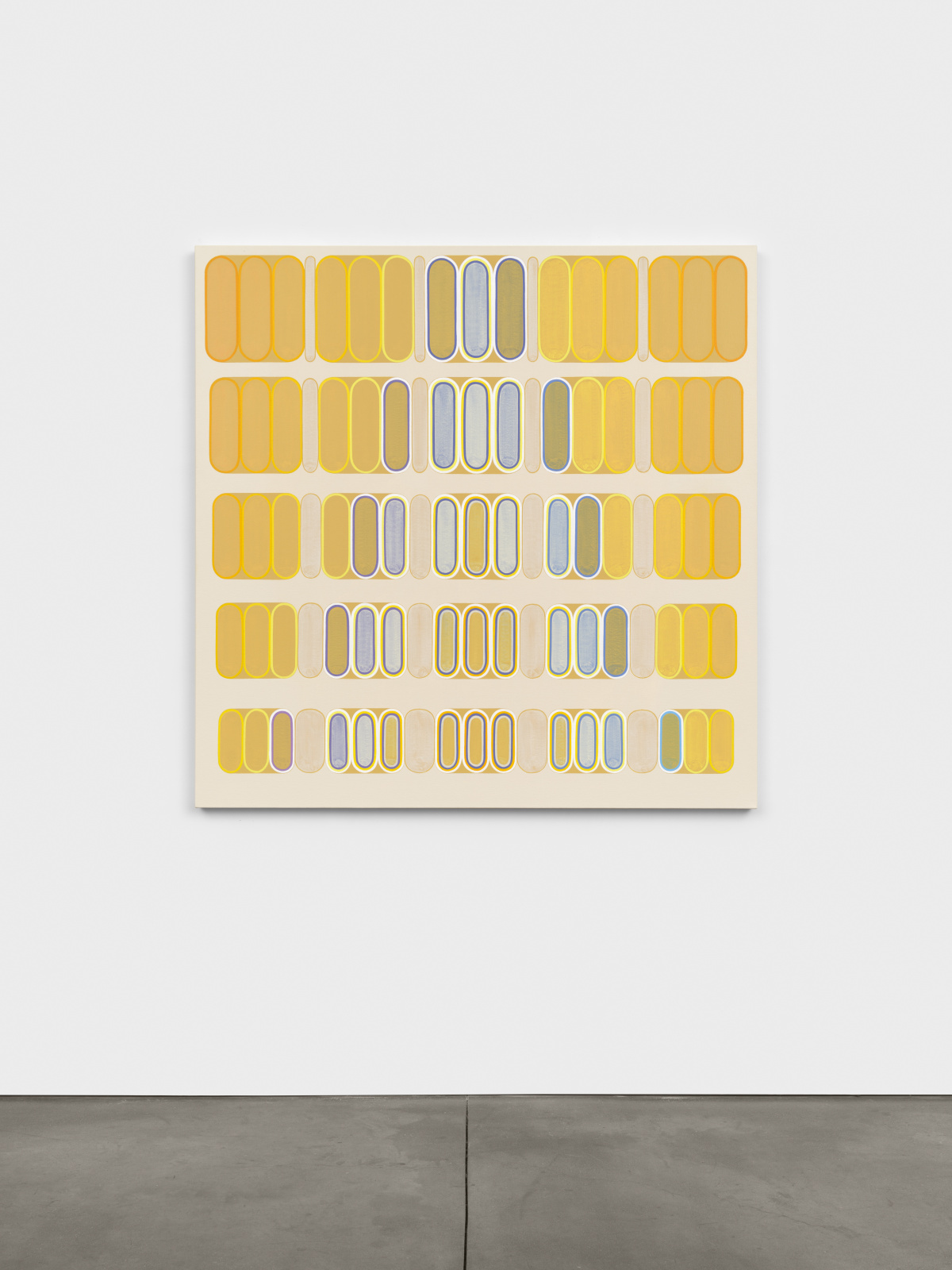

- “I started working with more color and became inspired by Tibetan mandalas, the Tibetan eye, optics, and textiles,” says artist Dan Walsh. Pictured: Rate, 2023 acrylic on canvas

- Demand, 2022 acrylic on canvas. Photos by Steven Probert, courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery NYC

As we walk through Dan’s latest exhibition nearly 30 years later, it’s hard to believe an artist with such rich form and scale had once been partly unaware of his own talent. He admits a career as a painter wasn’t always the plan.

“I originally wanted to study forestry and forest management,” he says. “I wasn’t a lost soul—it seemed interesting. Something where I could watch trees grow and smoke joints. I ended up adding some art classes into the mix at New England College. The teachers were impressed, saying things like, ‘This is your first painting? This is solid stuff. You ought to get yourself to art school.’”

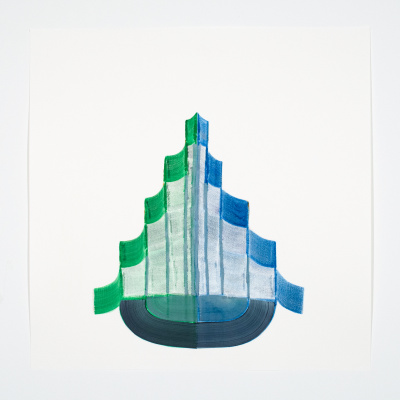

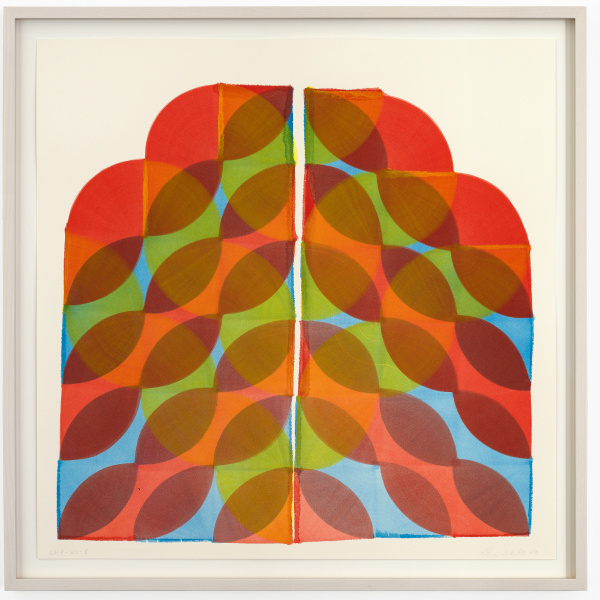

- As his career developed, Dan gradually introduced more color into his work. Now he describes himself as a full-blown colorist. Pictured: Reform I, 2024

- Reform II, 2024. Photos by Steven Probert, courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery NYC

With their encouragement, Dan pulled together a portfolio and transferred to Philadelphia College of Art (now called University of the Arts). Though he moved to New York for grad school and eventually had a brief stint as an electrician, he was committed to becoming a painter.

“I painted on weekends and nights, maintaining a good lifestyle and making lots of friends,” he says. “But I never left New York. By then I had painted through various styles—Willem de Kooning meets Henri Matisse in grad school, moving through different phases of art history, and ending up in minimalism. I started creating diagrams influenced by artist Peter Halley, focusing on painting as a model rather than an idea.”

In the early days of his career Dan’s works were minimal and playful. He describes them as “model paintings”—more like drawings of paintings rather than fully committed pieces, some utilizing black or yellow lines on a white background. As his career developed he gradually introduced more color into his work. Now he describes himself as a full-blown colorist.

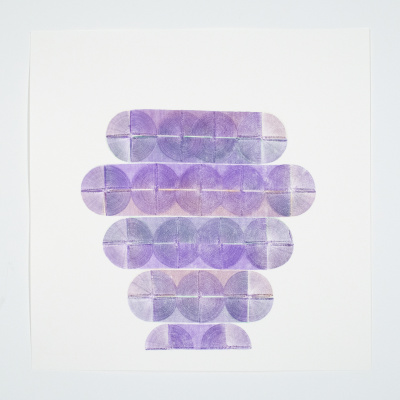

Step by step, Dan documents a process of addition and subtraction, introducing, removing, and reintroducing forms and colors in the work. Pictured: Bridge III, 2023 lithograph on BFK Rives 300g paper. Photo courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery NYC

“I started working with more color and became inspired by Tibetan mandalas, the Tibetan eye, optics, and textiles,” he says. “But really I was dealing with the grid before I realized it. Maybe it was my electrician background, but I was looking at electrical diagrams for the work as well. Those elements dictate my structure. There are a lot of pieces, and it’s all put together like tile work. I call the form I use a ‘codified brush stroke.’ For me they’re easier to make than to tape something and paint, but to get that detail takes some time.”

Most of the time Dan lets the process do the talking. Early iterations of his paintings begin as mathematic scribbles to ensure each element lines up properly. The early planning (and making color decisions) are the most difficult steps for him—the rest is intuitive. He also has a long history of photographing his paintings as they progress in the studio. Step by step he documents a process of addition and subtraction, introducing, removing, and reintroducing forms and colors in the work. He never abandons an idea, only finishing when he feels a painting reaches its “natural, economic conclusion.”

- Decoy 1

- Decoy 10

- Decoy 32

- Decoy 41

- Decoy 18

- Decoy 21. Photos courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery NYC

“I have some of that Matisse dictum in me where I want to make it look easy,” he says. “I’m trying to sneak in a very programmatic approach, but I’m cheating. I’m manipulating those things dramatically behind the scenes. Before I finish a painting I’m weighing out: ‘Is it physical enough? Is it too graphic?’ I thought my piece ‘Call’ was too graphic before the white horizontal strokes were added at the end. It felt too close to a Persian rug or something.”

Occasionally a painting unfolds in unexpected ways. He appreciates and welcomes these rare moments.

“In my painting ‘Reform II’ I stacked five brushstrokes onto each other to create individual shapes,” he says. “Everyone tells me it looks like circus tents. I initially expected to fill each stroke in with the same color. Instead I filled the top stroke with a different color—and that really made it pop. The new color put pressure on the shapes in a unique way. I don’t seek it out, but in the end I do believe in beauty and beautiful things. It was a wonderful surprise. Honestly I wish it happened more often.”

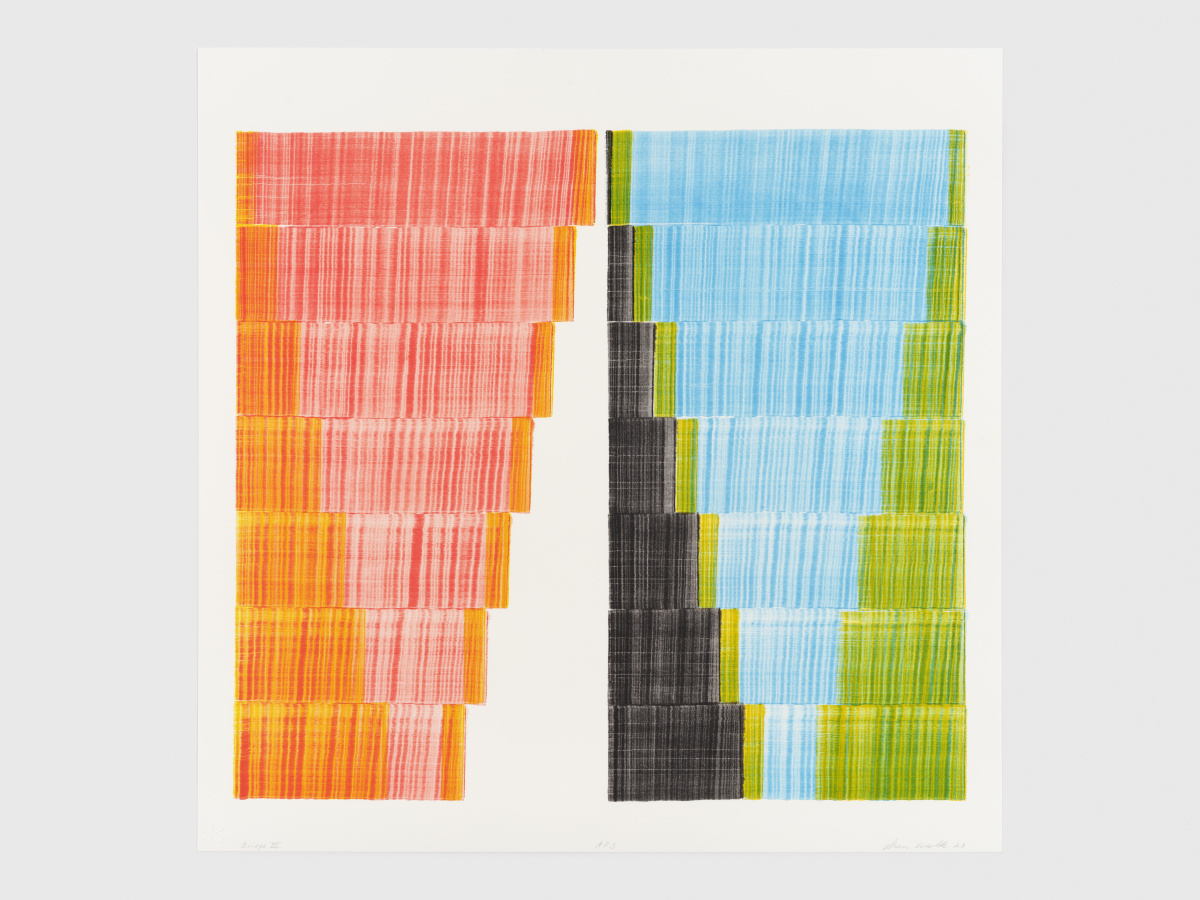

LHP-WC 8, 2023. Photo by Cedric Mussano, courtesy Galerie Tschudi

The artist seems curious about the prospect of inviting more freedom into his practice. When asked what type of painting he would make if he were to abandon all structure, the first artist that comes to mind is Günther Förg. He quickly Googles images of Förg’s work, showing me pieces with a Cy Twombly-esque scribble that pictorialize the activity of artmaking.

“Förg does a lot of hatch paintings,” Dan says. “They just seem like a natural place to go—I don’t know why. It feels like it might be fun to try. I think it would be healthy for me. But on the other hand I really am a ‘plan ahead’ kind of guy.

“It’s been said many times that artists have to create limitations for themselves to get somewhere. That was the case for me early on. I limited a lot of elements for clarity. Sometimes I want to open to the world, but my process is so overwrought. I feel I’m consistently painting myself away from that. If an artist doesn’t have a contradiction, then you’re not true, right? There’s bound to be some conflict somewhere.”

Dan says he never abandons an idea, only finishing when he feels a painting reaches its “natural, economic conclusion.” Pictured: Demand, 2022 acrylic on canvas. Photo by Steven Probert, courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery NYC

Despite the temptation to diverge from his approach, Dan believes everything has been done already anyway. “There’s no free will,” he says. He says artists should protect their self-esteem and avoid attending fairs like Frieze New York to prevent feeling overwhelmed. “You just feel like a little ant out there,” he says.

Perhaps to combat stagnation, Dan refreshes his work by cycling through themes about every five years. He tells me he once dedicated two years to exploring triangular shapes. He also finds joy in handcrafting artist books, a labor of love he takes pride in.

“I originally started making these because I wasn’t happy with the way my paintings were being reproduced on a page,” he says. “Now I wouldn’t be caught dead without doing at least one book per year. My goal is to make it to 50 books; I’m at 44 right now. I spend a lot of time on that.

“The books are a way for me to entertain other ideas that aren’t pure painting, though a critic friend once said my books inform my paintings, and my paintings inform my books. I think that’s true. It’s all symbiotic.”

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 12. Subscribe today