On a busy street in Aubervilliers, a suburb of Paris, Clara Imbert pulls open a heavy metal door, giving view to what looks like the backlot of a Hollywood movie set. The industrial complex, formerly owned by the perfumery LT Piver, has been recently transformed from abandoned factory to artist community thanks to the help of real estate giant Société de la Tour Eiffel (they manage a tower by the same name that you may know). Rechristened with the name Poush, the complex is now home to 250 Parisian artists. “I’ve known one of the people who started the project for years. He was talking about it even before it happened, and I thought it sounded really good,” Clara tells me as she offers me coffee and chocolate carefully presented on her handmade steel welding stand.

Clara happens to have been one of the first to join the creative community. She shares her workspace with six other artists specializing in all variety of materials—stone, ceramics, glass, and, of course, metal. Her space serves as working studio and a gallery space. She uses a portion of her welding gear to create intricate metal sculptures.

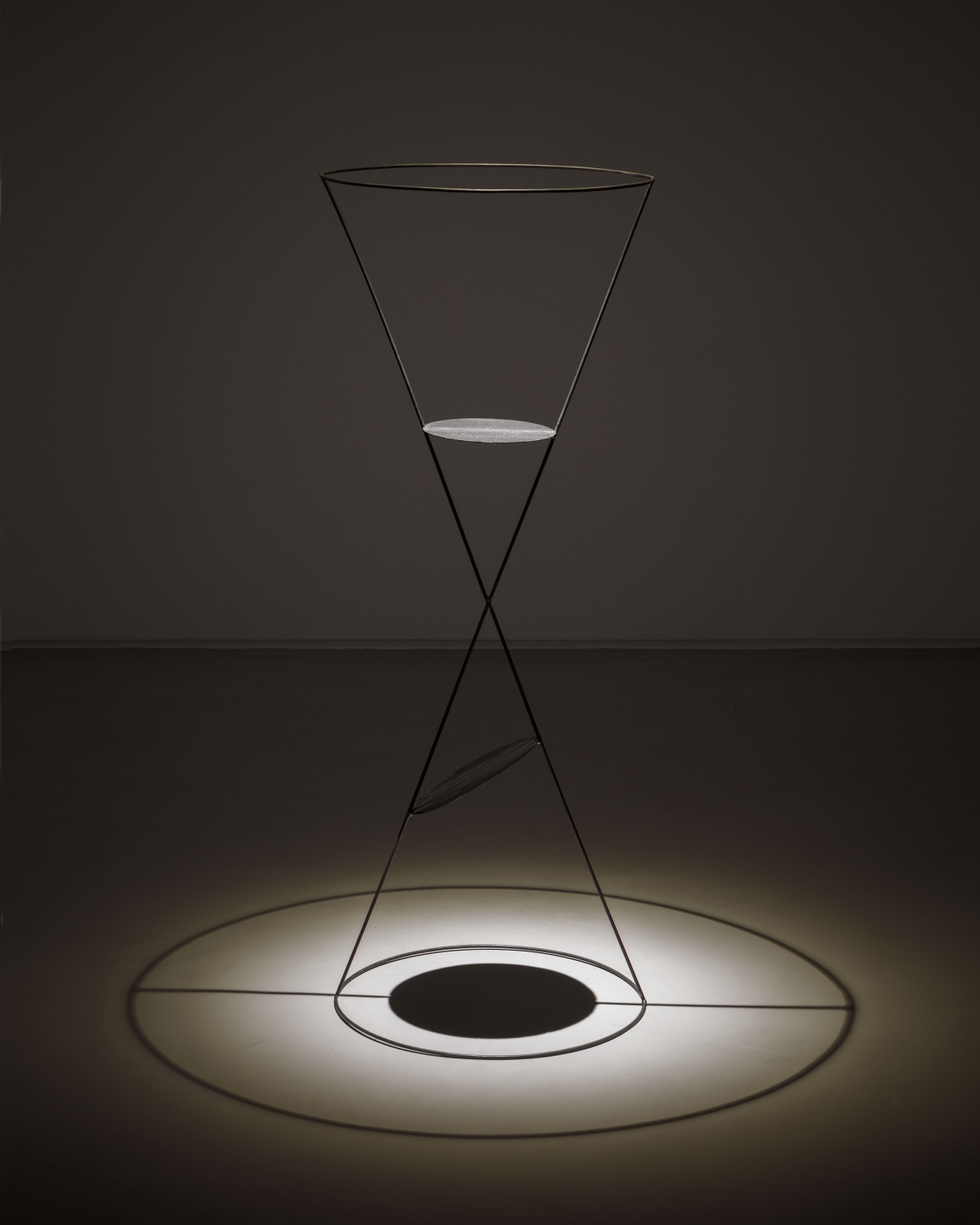

- “Shadow Object 1239,” 2021, Fine Art Print on Baryta Hahnemühle paper, nielsen frame, museum glass. Photo by Photo Documenta, Courtesy of Galeria Foco

- “Suspension,” 2021, Polystyrene, resin, polyurethane paint, magnet. Photo by Photo Documenta, Courtesy of Galeria Foco

At 18 Clara left Paris to study fine arts—specifically photography—at Central Saint Martins in London. “I really wanted to leave Paris, live abroad, and be fully myself in a new place, completely free,” she says. In London she found a new passion, turning scrap metal into sculpture contemplating big themes—not quite “What is life?” but adjacent questions, like “What is time?” and “What is space?” Her sculptures transform metal, glass, and mirrors (the same materials that comprise a camera) into instruments and gadgets that measure, or at least reflect, these themes.

In her last year of school Clara met three artists who became close collaborators and friends. Together they moved to Lisbon to save money to move back to London—but after a few months Clara came to love Portugal. She developed a relationship with local Galeria Foco, and before returning to her hometown Paris spent time between Portugal and her father’s house in the Northwest countryside of France.

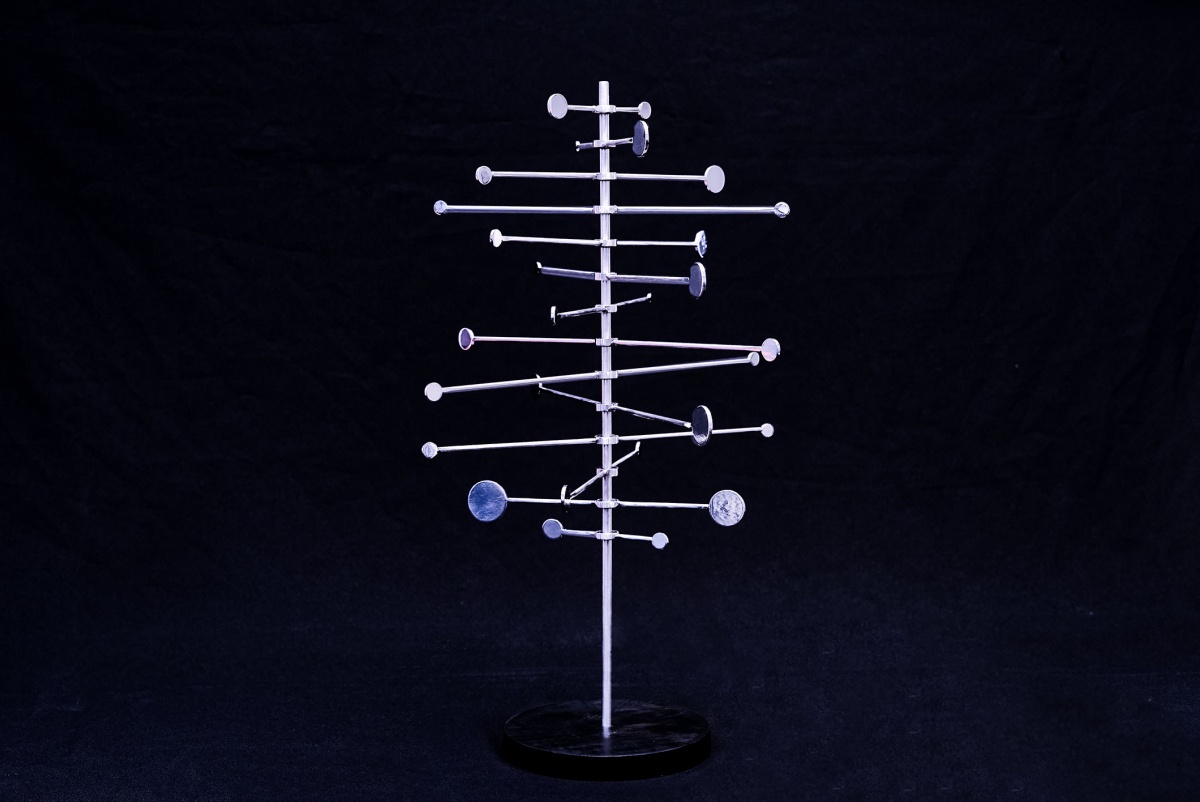

- Clara likes to design objects and instruments, like “Artefacts,” using symbols and myths from the past to give them new meaning. Photo by Chris Force

- “Relic 0.01,” 2022, stainless steel. Photo by Chris Force

In Paris today Clara works with the young, nomadic Hors-Cadre Gallery. “It’s important to have that kind of support as an artist, especially when you do have to think about selling the work or getting funding to create a bigger installation that obviously you cannot self-fund,” she says. She notices the competition in Paris is higher, perhaps, than it was in Lisbon, just due to the sheer number of artists in the city. Being part of Poush helps—the project offers greater visibility as well as resources and support for their artistic development, production, and administration.

Clara says the best part of Poush is the collaboration between artists, the ability to hold conversation around their works, incorporate new techniques, and work together to push their practices further. As we have a friendly chat in her studio other artists and collectors pop in and out to say coucou and have a look around, her friends joke about the heat and the impending chill of winter (the studios are sparsely heated). When our conversation turns to her work, I ask how she describes her sculptures. “I love the word instruments—instruments that measure depth and aerospace. I think that’s what I like about sculpture is that as an object you have the possibility to turn it and have different angles, different points of perspective.” Lark Breen contributed to this article.

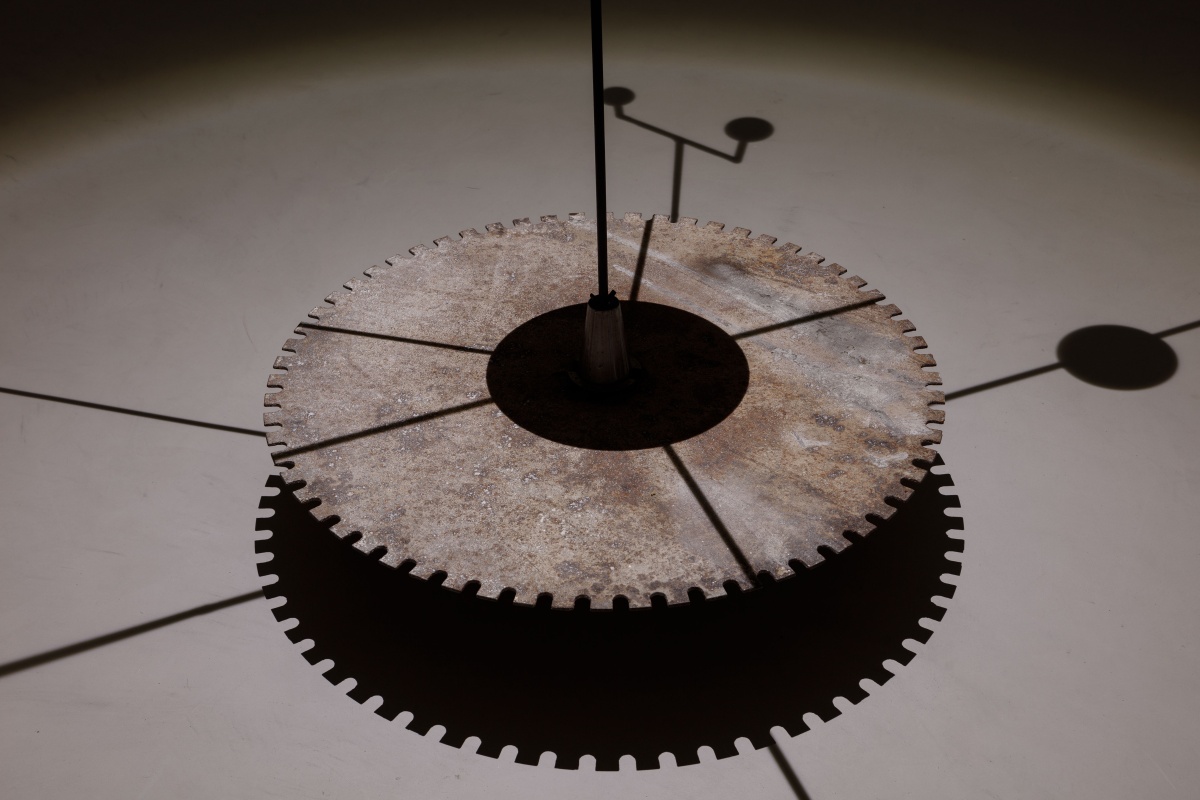

- “19.13UA,” 2021, steel, aluminium, optic lenses, motor, projected light. Photo by Photo Documenta

- “19.13UA,” 2021, steel, aluminium, optic lenses, motor, projected light. Photo by Photo Documenta

When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

I do not believe that one chooses to be an artist. It is something that happens over time, and in my case my mother gifted me a camera when I was very young and enrolled me in a silver photography class. That probably sparked my relationship to the image and taught me how magical it can be. To be able to depict the world and shape it as you want is a powerful feeling.

“Shadow Objects,” 2020, steel installation. Photo by Photo Documenta, Courtesy of Galeria Foco

How did you transition to working in sculpture?

I started working with photography and the notion of the image and how the world and the eye converse in it. The French word for image is also an anagram for magic. The transition into sculpture occurred with this study and reflection around the encounter with an object—in my case through the lens of a camera.

I began to experiment with space by printing or projecting images on different materials. Another work was about deconstructing the camera itself and using all its elements. I then created a sculpture, and through it you could see a projected image of a horizon line in the desert. This project piqued my interest in apparatuses that allow us to capture and measure the invisible—from telescopes to microscopes—and I started imagining devices of my own.

“My work comes from my fascination with scientific, mathematical, and philosophical theories. I believe that the role of the artist is to rethink realities.”

Did you learn to weld in art school?

At Central Saint Martins we had access to a vast range of workshops focused on different materials, but you have to choose; you go to the workshop, meet the technician, and you kind of have to fight a bit for what you want. It’s a very good thing because they’re preparing you for the future. You’re always going to have to fight for what you want.

I passed by the metal workshop every day and I was fascinated by the smells and sounds but a little bit scared. It smells of burning and blood and noise. It’s very intense. I was collecting unwanted metal pieces left outside, and one day I decided I needed to assemble these. I went inside and met a technician named David and wonderful artists as well. I made a point of going to the metal workshop every day, and I would always start with a little question that ended in a 30-minute conversation of how I can build something. It offered a great framework for learning, but you learn a lot alone, too. You have to just figure it out yourself sometimes because it gives you confidence.

“Orrery,” 2021, steel, stone. Photo by Photo Documenta, Courtesy of Galeria Foco

How would you define your style? Or how do you think your work fits into the art world?

My work comes from my fascination with scientific, mathematical, and philosophical theories. I believe that the role of the artist is to rethink realities and explore them in a new language. I am not necessarily concerned with how my work fits in the art world. I think more about its place in relation to our history, as in my work I collect all sorts of symbols and myths and give them new meaning—hopefully a poetic one.

What other artists and experiences inspire your work?

In 2017 I went to Naoshima and Teshima islands in Japan, and it was one of the most sublime experiences I have had. For me it transcended everything that art should be about; there were James Turrell, Walter De Maria, and Claude Monet all living alongside each other.

- “Equation for an Ellipse,” steel, 2021. Photo by Photo Documenta, Courtesy of Galeria Foco

- “Circular Visions” in exhibition at Galeria Foco. Photo by Photo Documenta, courtesy of Galeria Foco

There are so many artists who inspire me: Hilma af Klint, with her exploration of the invisible and symbols, and Barbara Hepworth with her relationship to the material. I really like land artists because of their relationship with the landscape. They made this bold statement of working outside the gallery space in the ’70s, and the perception of art shifted completely. When I was studying, there was a moment…

They clicked with you.

Yes, it clicked, it did something. I love film, too, even though it’s very different from my practice. For example Andrei Tarkovsky creates such peculiar, almost palpable atmospheres. And in Stalker, the idea of a dystopian environment where the dreams of men can come true is daunting. I am very influenced by science-fiction, but some of those imagined worlds paint a dark, post-apocalyptic portrait of the future. With directors like Tarkovsky there is always some sort of hope in humanity, and this is essential. There are always going to be beautiful things and very difficult things in our world, so as an artist I hope to make people dream a little bit and go back to this inner child who is marveled by their surroundings.

“Indefinite Motion,” 2023, Stainless steel and treated steel. Photo by Marcio Vilela

What is special about your studio space?

I am lucky and happy to have a studio here at Poush, which I share with six other artists. It is very fulfilling to be in this community where we give each other a fresh eye on things and have passionate conversations. I think art today is becoming more and more collaborative, and it’s important to embrace that.

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 11 with the title “Metallic Rituals.” Subscribe today.