Chiara Stephenson is the creative force you didn’t know you were already obsessed with. This British set designer and creative director has made waves in the world of live performance and art installations, crafting some of the most visually stunning stages for an impressive roster of A-list artists from Florence and the Machine and SZA, to Alicia Keys and Sigur Ros. That ethereal, insane residency Björk had at the Shed that no one could stop talking about? That was Chiara. And you may have caught one of the 70+ shows around the globe on Lorde’s Solar Power tour. (Yep, that was her too.)

Chiara’s talent doesn’t stop at concert stages. She’s also lent her touch to theater and fashion, using her skills to translate an artist’s music, a brand’s narrative, and actor’s performance into a tangible, breathtaking environment. I spoke with Chiara recently while she was in Dublin working on a new play set to open at the Gate Theatre.

How’s Dublin treating you today?

It’s good. I love working in Ireland. In terms of theater, they’re good at it. It’s nice to be here.

I’m curious how you ended up where you are today. Did you always know you wanted to do this type of work?

Both of my parents are painters and artists, so I come from creativity. I didn’t have much choice. I was brought up with paint and creativity and artistic expression, I suppose. I went to art college, like any good creative person does, and took an art foundation course. Everything I made at school always took on a 3D form and incorporated a relationship with light.

I decided to get a theater design degree in Liverpool and then worked for two years for Christopher Oram in theater and opera doing model making and creating architectural maquettes. That evolved into working with Es Devlin and I ended up staying with her somewhere between eight and 10 years.

I love the variety and cross-pollinating across all different industries. Not only doing theater and opera, which I’d done for a few years, but branching into music, a bit of fashion, a bit of ballet, and live music events. The apprenticeship working with Es Devlin Studio was my training. It was just the two of us working when I began. By the time I left, there were seven or eight. It really grew.

About eight years ago, I flew the nest organically and tried to hold onto that variety. I had been working in music and theater and felt very comfortable with both tiny budgets and big budgets. I enjoy the contrast between the two and how both feed each other. When you bring the sensibility from one industry like theater into music, it works well. And then vice versa—theater sometimes needs a slightly punchier, fresher take in their world. I’ve found that working across those disciplines and industries, they all complement each other.

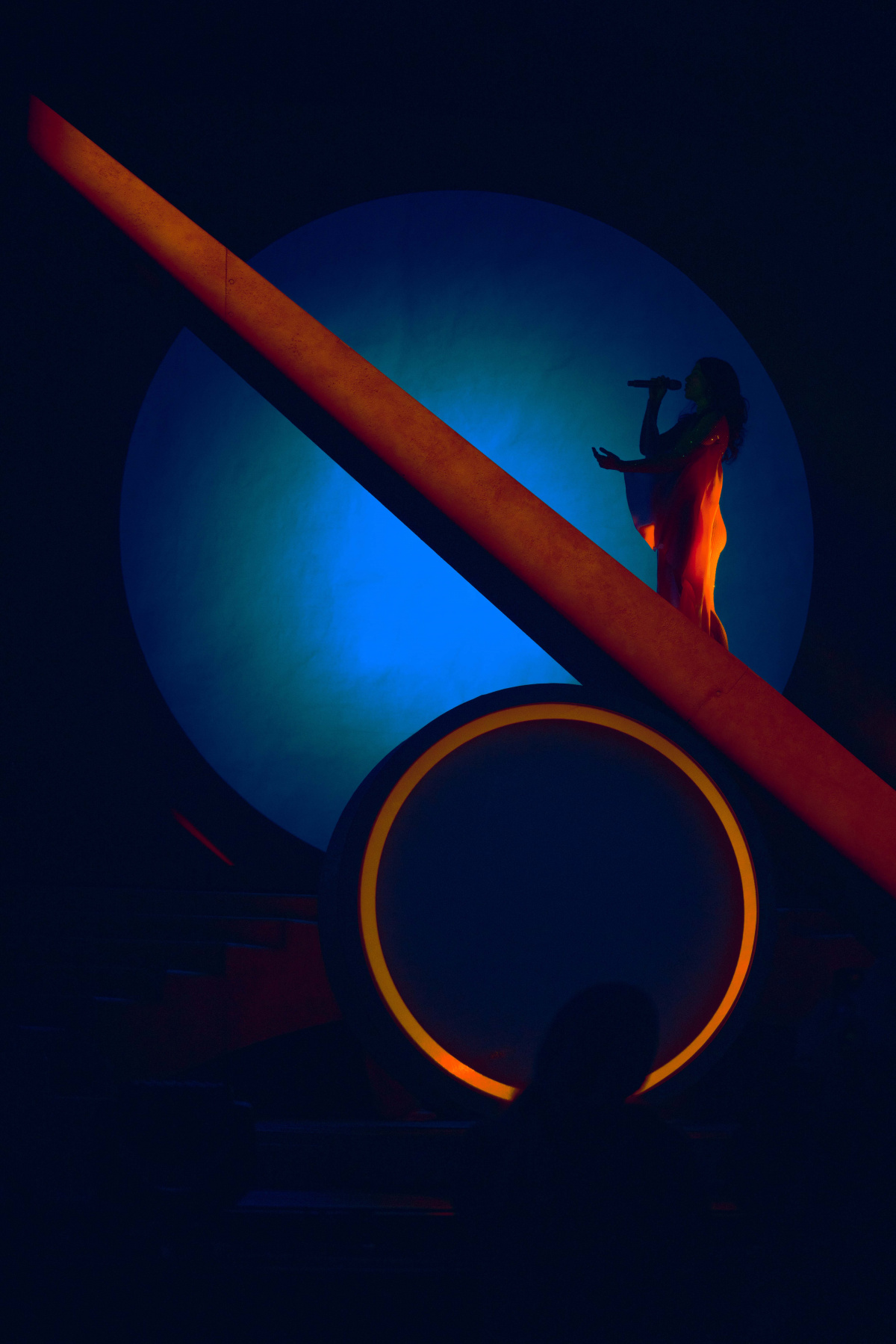

- Chiara Stephenson was the creative director for Lorde’s Solar Power Tour in 2022.

- Chiara turned to the work of Hilma af Klint when creating the stage for Lorde. Photos by Lauren Tepfer

I’m curious about the eight years you spent with Es. What was that culture like when it was just the two of you?

I think the greatest training I received when I was working for Es was how to be good on the ground. You can prep and plan, but when you’re bringing those things that have been planned for months and months and translating them into a live show, it’s important to be good on the ground and read the room. You need to read everyone’s position creatively and collaboratively and help communication lines between everyone whether it be the needs of the design, budget, or something else.

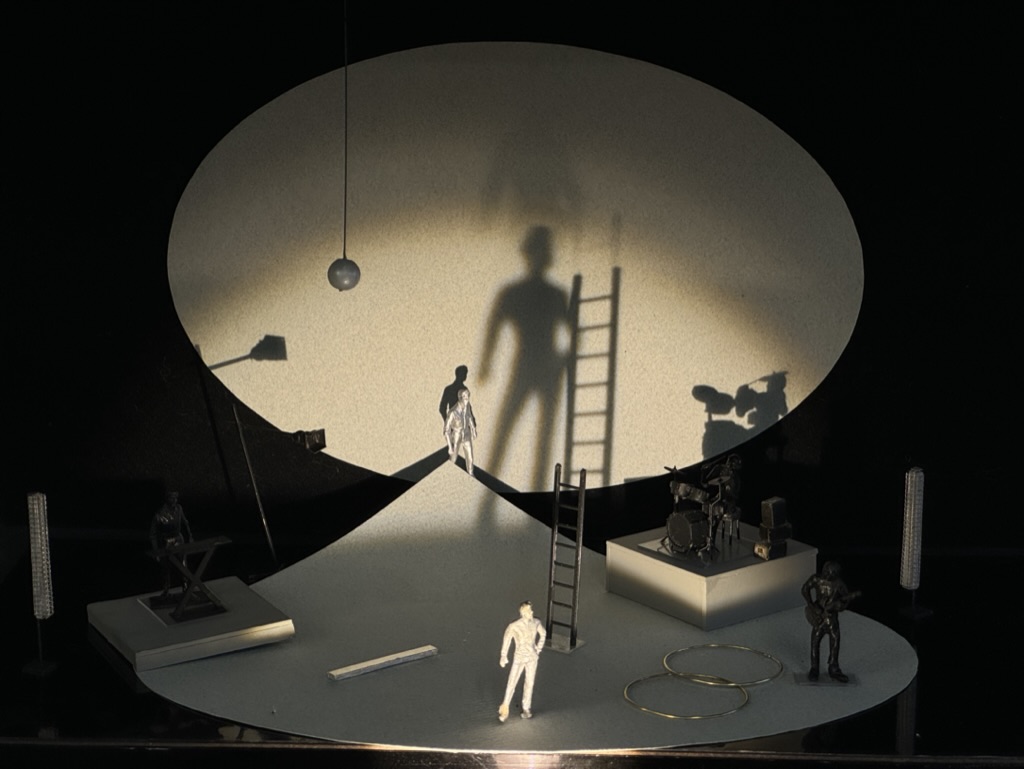

- Chiara worked with 1:50 scale mockups and flashlights to show Future Islands her idea for the show. Photo courtesy Chiara Stephenson

- Future Islands performing in Oslo. Photo courtesy Chiara Stephenson

I wanted to ask you about your early independent projects and how they’ve influenced your recent work, particularly with Future Islands. How has your experience shaped your approach, and how would you have handled the Future Islands project differently when you were just starting out?

The great thing about the more years you spend working in an industry, is the confidence in knowing how things will turn out. Even though each show is an experiment in itself, you can rely on your gut and intuition more, built on the knowledge of remembering how light reacts and works with certain textures, tones, finishes, or materials.

I used to design the form first and then add lighting later. Now, I always design with lighting in mind. It’s almost like creating a shape that will generate interesting light, rather than a shape to be lit. Knowing how unforgiving lighting can be—it can make or break a design—I work closely with Matt Daw, the lighting designer. The confidence in our shorthand communication, having worked on many shows together, like Lorde, comes from growing under the same design giants above us.

Feeling nervous about the result but confident in gut decisions, being ready to react and make changes when things aren’t working, is key.

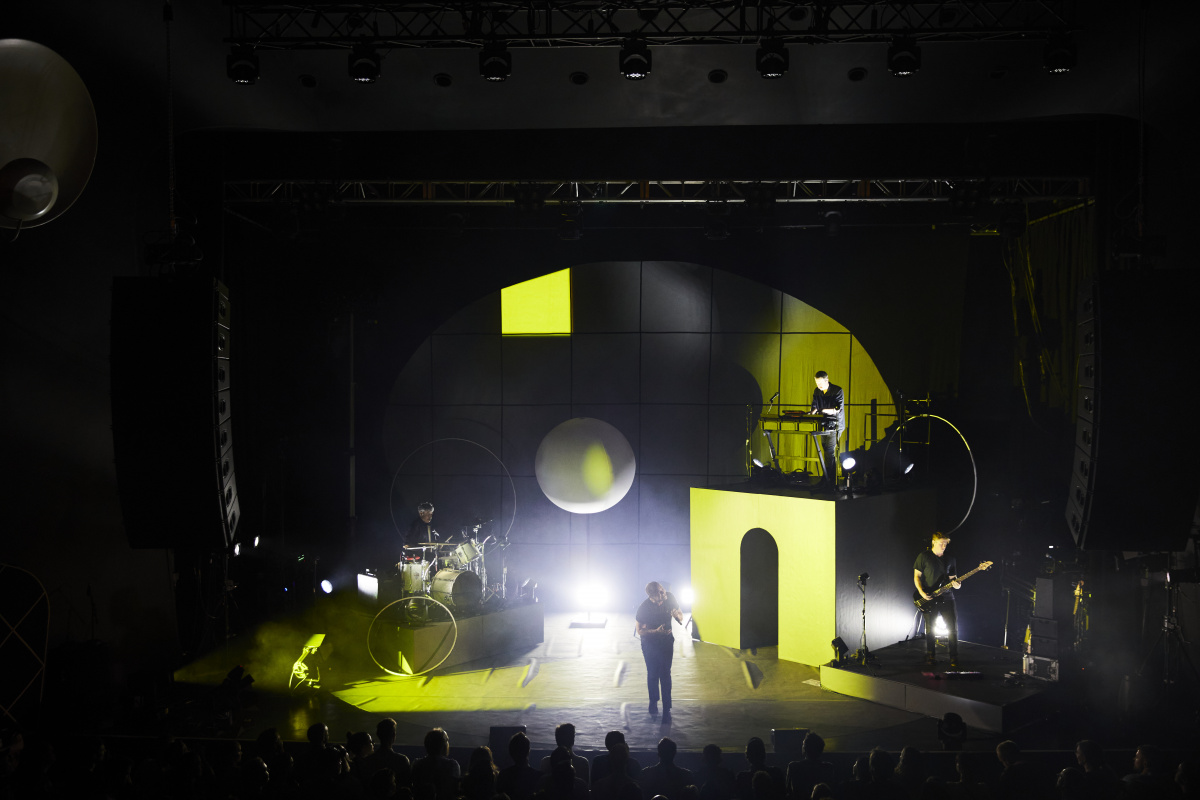

Every artist and band is different in their needs and wants. What was interesting about my first talks with Future Islands was hearing which of my works they responded well to when deciding who to collaborate with on a live show. They were drawn to my theater work more than my live show work, picking out very architectural theater projects I’d recently done. That gave me a sense of their tastes and aesthetics.

The band’s frontman Sam Herring, being an incredible performance artist, needed support that didn’t crowd him. We had to figure out how to give him space while elevating the more subtle performances of the rest of the band and tying them together.

We found shadow play to be a good way to unify the elements while giving Sam a playground of levels for performance. I tend to design shows like a toolkit with different ways to use or light it as opposed to sets that perform specific functions in sequence. It’s about providing a toolkit to draw out different aspects of the performance to suit each song and what Sam wants to do with it.

The set’s dramatic rings and floating balloon were inspired by the French photographer Gilbert Garcin’s work that often used paper cutouts and surreal backgrounds. Photo courtesy Chiara Stephenson

How does a project like this initially land on your desk? Does an email suddenly pop up saying, “Hey, Future Islands is interested in hiring you for a tour. Would you want to get on a phone call with them?”

I think it starts much like you described. There’s an interest to collaborate, and then very quickly, a call is had. I was heavily pregnant when that call came in, so there was a time I thought I wouldn’t be able to do it. But luckily, the band and Matt Ford showed patience. While I went off to have a baby, those creative conversations continued. I was lucky enough that after having our second child, I was able to come back to it, and there was still space for me to contribute and bring the final iterations of the design into being. The timing just worked out, and it was a challenge, especially considering the scale of touring.

It’s a joy to have children, but it’s also wonderful when you’ve been so absorbed in that chapter of life to stimulate your brain creatively, to strike the balance. This was a great show to return to work after that. There was a bit of a sigh of relief when I found out I was rehearsing in London [where I live] and not in Baltimore. That was great. We made it work with a short but super productive rehearsal period. You should have seen the truck; it’s a one-truck show, packed to the brim. There’s a lot of math on stage. Some tours can be very lighting-heavy, but this was both set and lighting-heavy.

Photo courtesy Chiara Stephenson

From that first email to the first rehearsal, how much time was that?

I always see music projects as taking around six months. It was a couple of months before I had the baby, and then maybe six to nine months total.

During this time, you’re having calls, exchanging keywords, and passing images back and forth. When you’re getting ready to present some formal visuals, are you making sketches or using rendering software? How do you convey your ideas?

After we were referenced out and had all the chats, certain ideas were brewing and percolating while I was off having my son. When I came back to the studio, it felt useful to make a 1:50 scale model of the design. I was there with torches and my iPhone light, putting gels over them to see how the light would work, getting a feel for it.

We quickly enjoyed the shadows and how they magnified the band’s forms on a back surface, which we divided into a grid. There was a mixture of linear geometric lines and forms combined with the organic shapes of the performers. The design came together very quickly, and luckily, the band took to it right away. It felt right.

I designed an archway, and there was some debate over who would be on the tallest riser. Standing seven or eight feet off the stage floor feels much higher when you’re up there than it looks. We eventually decided the keys would be up there, with drums on stage right.

Showing them the little maquette model was helpful. The nice thing about a model is that when you show an artist or a client a model, it’s not too finite. Sometimes if you go in too soon with beautiful 3D renders that are too perfect and finished, it feels like there’s no room for adjustments. I find that grabbing a model is tangible and allows you to shift things around without asking people to commit prematurely. Maybe it’s old-fashioned, but I love working with that format. It lets you show the lighting and how you can change those simple forms to give different songs different looks.

- Chiara’s work with Future Islands was bold yet flexible allowing the band to use the set like a “toolkit” as needed. Photo courtesy Chiara Stephenson

- Chiara’s work with Lorde on the Solar Power tour featured a geometric set of moveable stairs. Photo by Lauren Tepfer

I noticed some similarities in your work with Lorde and Future Islands. Your voice is clear. How much of your work is your art versus your craft? Do you ever feel that an artist’s direction doesn’t fit your vision? Or do you see your role as a craftsman executing the artist’s vision?

My job is to elevate the artist, but I’m also there to bring something different to the table. If everyone is a bit out of their comfort zone, we’re probably doing something right. It should feel a bit daunting and a stretch for everyone. I want the performers, the artist, Sam, and the rest of the band to feel happy. But there’s something you learn from that first show with an audience that you can’t see in a quiet rehearsal space.

That’s where you learn a huge amount about what works and what doesn’t. We made changes after the first show in Oslo, and even after the second and third shows. Sometimes artists aren’t sure if they’re happy, and there’s a lot of apprehension before a new tour. But I think a bit of nervous energy is healthy to create adrenaline and push everyone to want the best result.

Photo courtesy Chiara Stephenson

Have you seen anything on stage recently that you found remarkable?

Recently, it’s been limited due to having a baby. “Machinal” at the Old Vic Theatre was pretty spectacular. Also, “Circle Mirror Transformation” at the Gate was impressive. Sometimes, being in the industry, you notice details that distract you from fully enjoying a show. Generally my favorite shows aren’t ones with a set. It always has to do with the air and the silence between the lines of the play as opposed to a big scenic shift. What always moves me, and how I judge shows, is not necessarily by how impressive the set or the writing is. It’s about those moments that resonate emotionally. If I find myself moved over the course of two or three hours, then I consider it a truly worthwhile experience. Even if the play itself isn’t top-notch or the design isn’t exceptional, it’s those moments that stick with me and define whether I feel it was a good time or not.

Are there any artists or actors you’d like to collaborate with?

I’d love to collaborate with Olivia Dean and Maggie Rogers. I think they’re both amazing. I’m more interested in collaborating with people who want to create theatrical performances. Future Islands was great because they embraced creating a theatrical experience, akin to David Byrne’s “American Utopia,” which was beautifully crafted by Rob Sinclair. It’s exciting when different creative realms converge in music. My favorite music has nothing to do with it—it’s more about collaborating with people who are game for trying unusual things or going against the grain.

Is there a material or technology, due to availability, budget, or practicality, that you haven’t worked with but would like to explore? There’s so much happening in this space, especially with technologies like different types of screens and innovations. What interests you?

There’s an incredible company that’s recreating massive Roman statues, like 50 feet tall. Scaling up sculptural and organic forms is something I’m eager to explore. While I’m confident with pure geometry, which I’m becoming known for, I’d love to incorporate more organic forms. You can do it in many ways too—with inflatables or large-scale 3D printing, like Jeff Koons’ iconic poodle. The technical infrastructure around live shows can handle such surprises, adding unexpected organic shapes that blend beautifully. I’m interested in stretching into this realm.

Do you see a significant future in virtual reality? Have you experimented with it or are you curious about its potential?

A few years ago, I worked on an exhibition at the Barbican Centre on an exhibition called “Virtual Realms,” where we worked with VR-rooted studios to create interactive art experiences. It’s intriguing how art intersects with VR. “Experiential” is a word everyone has used over the past 5-10 years. However, for me, the authenticity of live performers connecting with an audience is paramount. While I’m open to VR, I’m more drawn to the raw, human connection experienced in live performances.

Photo courtesy Chiara Stephenson

What are your thoughts on Yondr bags?

I’m all for them. How many shows have been wrecked by 8,000 iPhones in front of you? At my height, I definitely support using these bags. It enhances the purity of the experience. It’s about being present in the moment.