Carl Gustav Magnusson’s home and studio is impeccably chic. The space he shares with his wife, architect Emanuela Frattini, on the Lower East Side of New York City has floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, not a single space left for new books, a sprawling living area (at least by NYC standards) arranged with equal parts good taste and intricate symmetry, and a fabulous red Eames Chaise. That chaise model was among the first pieces he worked on at his first industrial design job at the office of Charles and Ray Eames in 1966. Fresh out of the Chalmers Institute of Technology in Gothenburg, Sweden, a young Carl sent Charles Eames a letter and what he calls “a pathetic little sketch,” asking the lauded American architect for a job. It worked, and what followed was a series of opportunities that took Carl around the world, to California and New York, to Paris, London, and Milan (where he met Emanuela in the mid-80s). One of those opportunities was at Knoll, where he rose through the ranks over the course of 30 years to become the firm’s executive vice president and director of design, commissioning world-class designers like Alessandro Mendini, Ross Lovegrove, and Richard Sapper on his way up.

Frank Gehry and Maya Lin were among the incredible designers you commissioned at Knoll. What was it like to work with some of these architects or designers?

Architects or designers, in this case they were doing the job of designers. Everybody was as individual as they are. Sometimes it was very easy and fluid—they already had an idea of what they wanted to do; sometimes they wanted to have a brief and stay very close to the brief; other times they interpreted and reinterpreted again; sometimes the process was quick, sometimes very slow, depending upon their understanding of the processes required to manifest an idea in that particular material. You can prototype and start manufacturing in the material of wood very quickly, whereas in plastic the tooling cost is extremely high and it takes a very long period of time to get the tooling made for the plastic—that can be a year in itself—plus often a half-million dollars in getting that done.

All of those variables bring one back to the statement that every designer is very different to work with and you have to work to get the very best out of them. I hope in most cases we were able to do that, and of course we hope the product will be very successful for the company and the designer.

‘My definition of design is: Design function with cultural content.’ COURTESY OF CARL GUSTAV MAGNUSSON.

How did you decide who to commission?

Sometimes the ideas came directly from our president, who had some very strong thoughts on it. In this case it was Andrew Cogan. And sometimes it would be heads of marketing or, for example, Liz Needle, who’s now president of KnollStudio. And of course I had my own cadre of people who I thought were extremely talented who we might give consideration to. We would discuss it together and see who would be the most appropriate designer for this particular commercial opportunity. If we needed a system that would be a completely different choice than needing a side chair, for example, in a residence. So to identify a systems person, such as Robert Reuter, we would need to have people who were technically skilled and also had a sense of the commercial opportunity for it because nobody has time to go back and redo it and rethink it endless times. We always had time to rethink it somewhat, which is very healthy in the process of developing a concept.

In other cases it would be very appropriate, for example, for Maya Lin to do a piece that was just an elegant statement, knowing full well that the commercial results would be very different right from the beginning, but it was an important thing to do. One of the great things about Knoll was that we often chose to do the product not for the money, but because it was an important continuation of the design legacy and direction that was set by Florence Knoll.

How often would you find yourself struggling between maintaining a design legacy and pursuing the best financial opportunity?

I don’t think there’s a contradiction at all. It’s a question of how you lay it out, how you plan it. A high-commercial product such as Don Chadwick’s life chair I believe is a culturally important addition to the design history and it’s a very high volume piece, it’s very reasonably priced, has excellent function, and it’s very important within the canons of design that I believe and am committed to, that we need to have good products that are completely affordable. And they will naturally look different, for many reasons, than a piece that Frank Gehry would do in aluminum or in bent wood that are intended to be more of a cultural expression. They both have their equal place. They are not compromises, they are a result of a very rational balance of “what are the priorities?” and “what is the goal?”

The esteemed industrial designer talks great design (among his favorites are Muji and regular old blue jeans), bad design (the Toyota Prius), and more from his studio. COURTESY OF CARL GUSTAV MAGNUSSON.

What do you make of your own legacy at Knoll?

It’s a bit early to think about a legacy, but I hope I was able to contribute, over my 30 years, a continuation that would stay within the company principles of design and also be commercially viable and profitable so we could go on to the next product. I believe that was accomplished during my tenure, with a few hiccups, of course.

What do you see for Knoll in the future?

The future of a furniture company is solving the problems of interior and, in fact, exterior spaces as it relates to work in particular. It’s understanding where the market is moving. It doesn’t make any sense to put together an office landscape system that is the Dilbert style that has very high panels; we’ve moved beyond that. It’s been a very long transition. The move toward an open office began in the ’50s and we actually now, 70 years later, have not accomplished it yet, but that’s the direction we’re moving in so people are able to work together unencumbered by continuous crate-like divisions between us and communication flows better.

And of course all of this has been made possible by the ability to work digitally and remotely. It’s a continued question of listening to “where are the needs” and then supplying that. I don’t believe furniture companies decide where things are going. If they listen carefully enough they satisfy those needs. And they might steer it a little bit, a few degrees, but in general it’s a question of listening and then creating answers that the market will respond well to and create a profit, so the company can continue to do useful and fun things.

Carl Gustav Magnusson’s New York City studio is lined with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and of course a beautiful Eames chaise. COURTESY OF CARL GUSTAV MAGNUSSON.

How have things changed in the transition from a pre-digital to post-internet era?

Like the French say, everything’s changed and nothing’s changed. The process is much faster, the visualization is extraordinary, to be done through CAD versus drawing by hand. And 3D modeling today can be done directly from the CAD files. The speed, accuracy, and economy of developing a product has been wonderfully exponential. What one has to be careful about though, if you move it too quickly, you may not be able to absorb the reactions of reviewing something and thinking about it. So the other side of it is, we’re still working in offices, we’re working in many different offices now, smaller spaces, more open spaces, and in that way I would say not much has changed. People still sit at desks and sit on proper chairs. The layout’s changed very much. Google particularly has been a catalyst to changing the formality of spaces to attract a younger, highly educated, digitally competent employee, but that may also be a pendulum that starts swinging back as we start viewing some of these interior spaces as having a rather kindergarten look. So it may well be swinging back or perhaps in another direction. Either way it’s very interesting: It’ll be very interesting to contribute to it and to observe its movement over time.

What are some obstacles you encounter during your creative process—mental or physical?

My own ignorance of how to move forward with something in processes. For example, not understanding the manufacturing process is going to demand time, talent, and funds to make into reality and also the obstacle of being overly anxious to get things done. Impatience. And that can cause its own problems, frustrations. Certain things, even at their highest efficiency, can only move at a particular pace. My own ignorance is the obstacle, and that you find in everybody else, too, when you’re trying to work together. And I say that in a benevolent manner, not necessarily negative.

How do you overcome the challenge of your own ignorance?

Trying to figure out efficiencies in various processes, what’s important, what’s not. Removing those things that are irrelevant to the situation that will have no impact in the end. Focusing on how do we get it hopefully done correctly the first time, or at least the first one-and-a-half-times, and often that has to do with bringing in very smart people to take a look at it also. My wife Emanuela, as an architect and as a businessperson with an MBA from NYU, is an excellent critic when it comes to the aesthetics, functionality, and also the commercialization of the thing. You need to have people around you that you can trust, you ask the question and you cannot be too concerned if they don’t like it, because there’s probably a reason for that, and you can modify the approach, try something else, and move it along in the process. You become more fluid in time with how to take a concept, move it forward, and put it into reality.

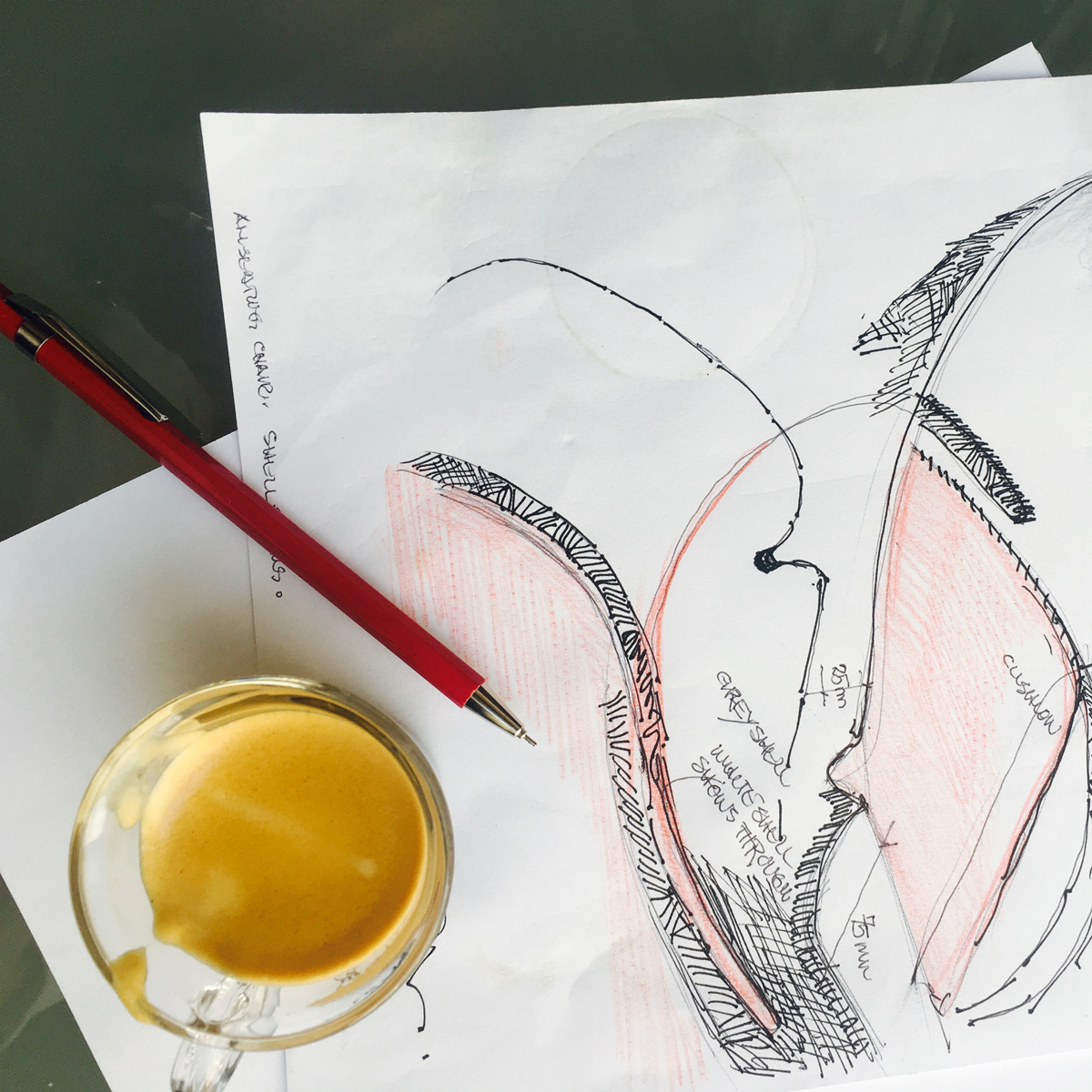

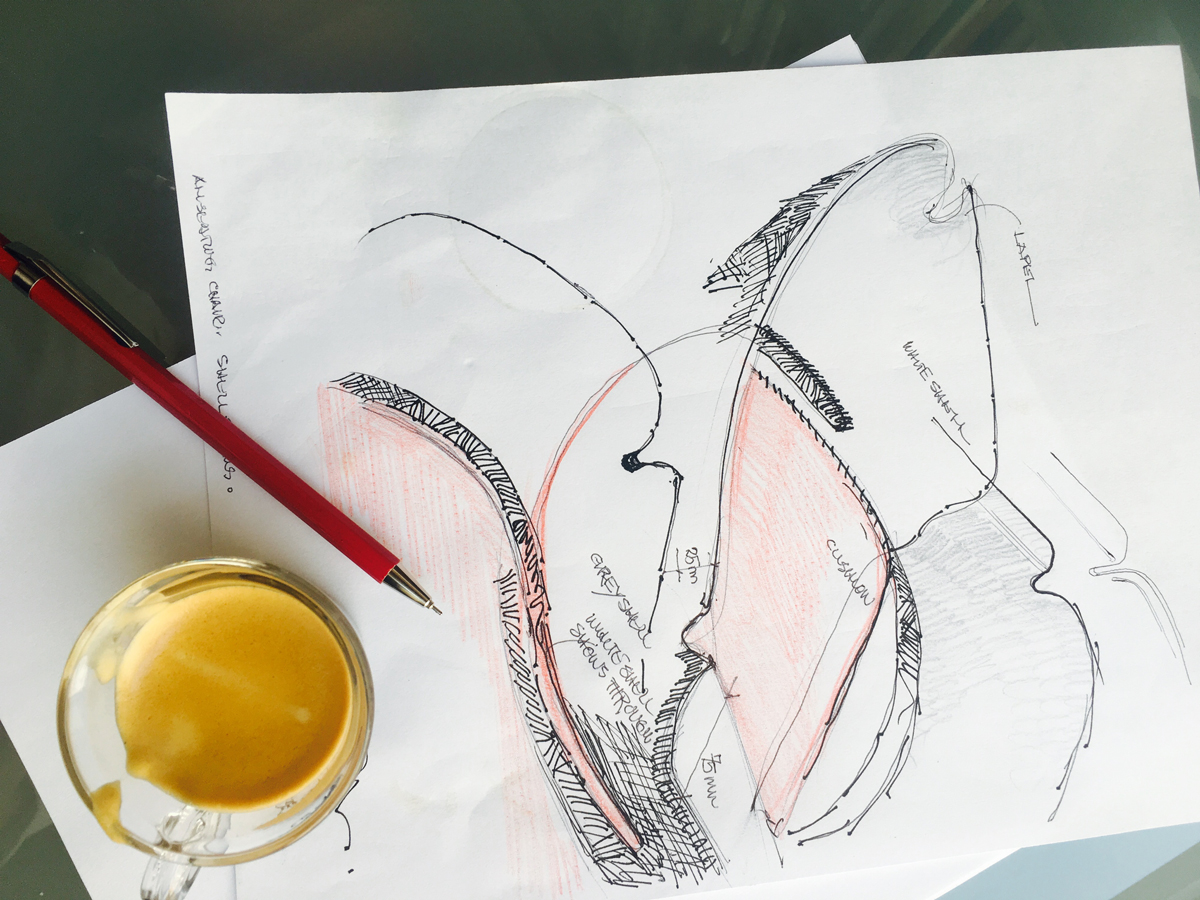

COURTESY OF CARL GUSTAV MAGNUSSON.

What do you consider to be your biggest failures?

I put failures and successes into two different categories. One is commercial failures and one is cultural failures. I actually can’t identify them because of contractual reasons, but I can tell you there is very little correlation between what wins awards and what is a commercial success. This came as a bit of a surprise to me, and maybe it’s because at the end of the day the customer makes a commercial decision and not the designers. The designers recommend it, that’s very important, but often it’s the actual client who decides whether this is going to be a success or a failure.

And on a personal level?

One’s life is filled with little failures that one learns from and changes tack to move forward. And personal successes, it’s obviously family and the expanding fulfillment of that happiness.

Where does Carl Gustav Magnusson find inspiration?

I walk a lot. I usually swim about an hour a day, and I often walk about an hour or more depending on the weather and I just look at things. Of course I go to museums and things like this, but my real inspiration is just watching every day, just observing. Not from an ethnographic, profound manner, but just looking around and seeing what people are doing, what’s in stores, window shopping, browsing, noticing great graphics, simple things that are done unconsciously well and learning from that. I’m endlessly inspired by areas outside my own discipline, I’m not sure how it manifests, but I’m endlessly inspired by master musicians such as Bach. I’m inspired by art, even though I truly can’t figure out art. It’s difficult just because I’m used to three-dimensional things. It’s not a discipline I can comprehend to the point where I can contribute.

In industrial design, objects are very easy for me to digest because I began drawing at an early age, 12, and I’ve continued to draw throughout my career. I find myself drawing things subconsciously that have inspired me. How books are bound, how shoes are made, the craft of leather, the craft of woodwork, metalwork, the blowing of glass. My definition of design is: Design is function with cultural content. It has to have a function, or quite frankly then it is art. And it has to have cultural content or it is just a piece of dumb materials. It needs to be the confluence of those two.

I’m inspired very much by automobiles and I loathe uninteresting things like Priuses. Why would we create anything as banal as that? Those are the types of things that are simply mediocre and what we as designers need to do—it’s very important to be able to do normal things, a spoon. What Muji does, unpretentious, normal things, but they’re not banal. They have an intellectual content to them that is a definition of good design, everyone understands it. You don’t have to be educated in design to understand it. You don’t have to know that it’s good or feel that it’s good, it just is.

Read more furniture and industrial design stories at Sixtysix Magazine.