Brittany Nelson is an artist specializing in camera-less photography and appropriation, employing 19th century chemical photo processes to reveal themes of distance, longing, and failed attempts to connect. Informed by science fiction, space, and time travel, her work moves beyond merely reviving traditional techniques.

—Gianna Annunzio

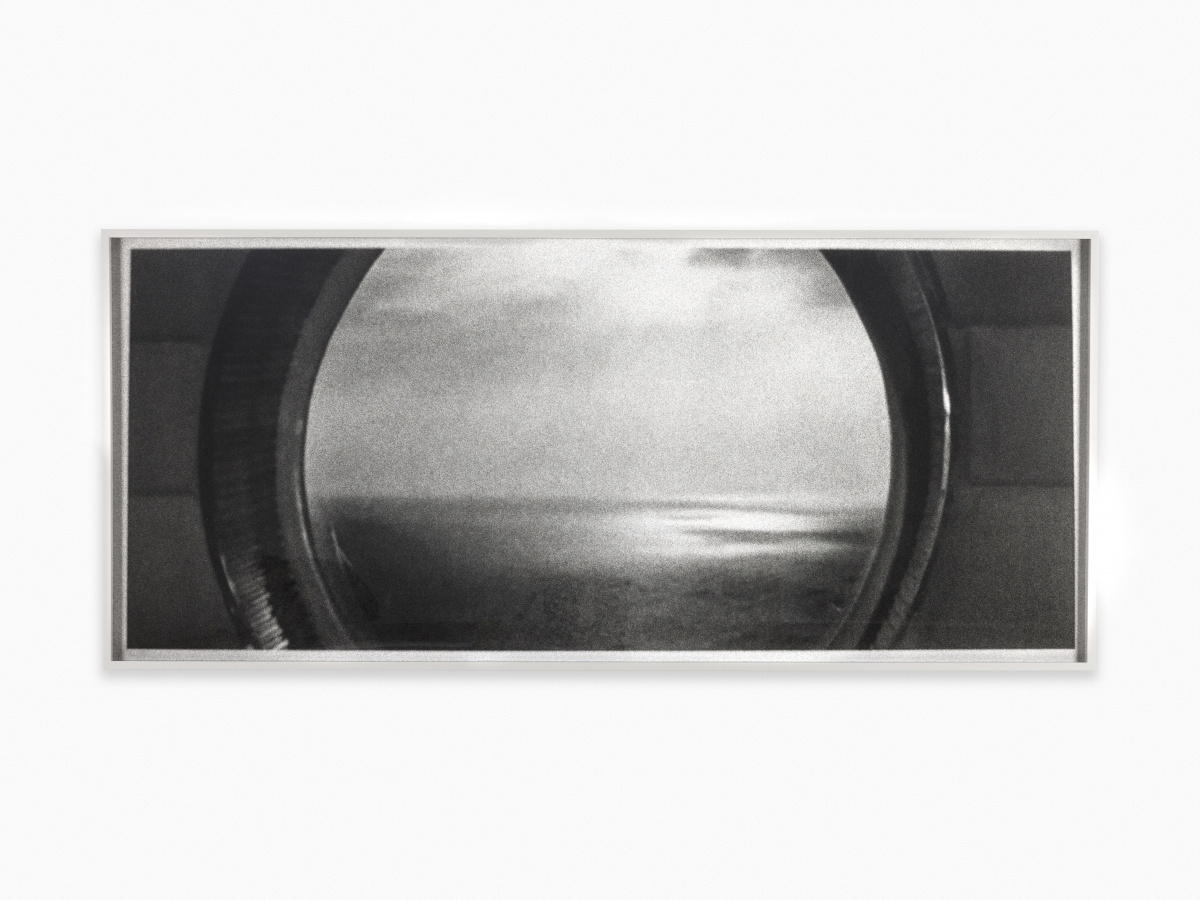

Solaris Ocean #1 unique gelatin silver print by Brittany Nelson. Photo courtesy Evan Jenkins

Gianna Annunzio: You work with so many unique photographic chemistry techniques to develop your work. What makes the process so appealing to you?

Brittany Nelson: What I love about photography is that it likes to keep you at a distance. In a photograph you are never viewing the thing itself, but a representation of it. The camera protects you in social situations. You have permission to look at something or someone closely, but you’re protected from the obligation of social interaction. As a young, closeted person in a very conservative and isolated town, having a camera became a haven.

- Dark Sea from Brittany’s “I Wish I Had a Dark Sea” installation at Le CAP, Centre d’art Saint-Fons, France.

- Roll 18, image 9. Artwork and photo by Brittany Nelson

My infatuation with it began in my high school’s photography dark room. It was under the stairs. At that point all the photos for our school yearbook were on film, so I ended up teaching myself a bit. I loved that environment—the low red lighting, the chemistry, all of it. I could lock myself away and problem solve all day. It’s very logical. I like the science behind it, but there’s also so much freedom. You can be a scientist and poet at the same time.

Eventually when I went to college at Montana State, I continued pulling crazy hours in their dark room. That’s where I met Christina Z. Anderson, my professor and mentor who wrote the book Contemporary Practices in Alternative Process Photography among others regarding 19th century photography techniques.

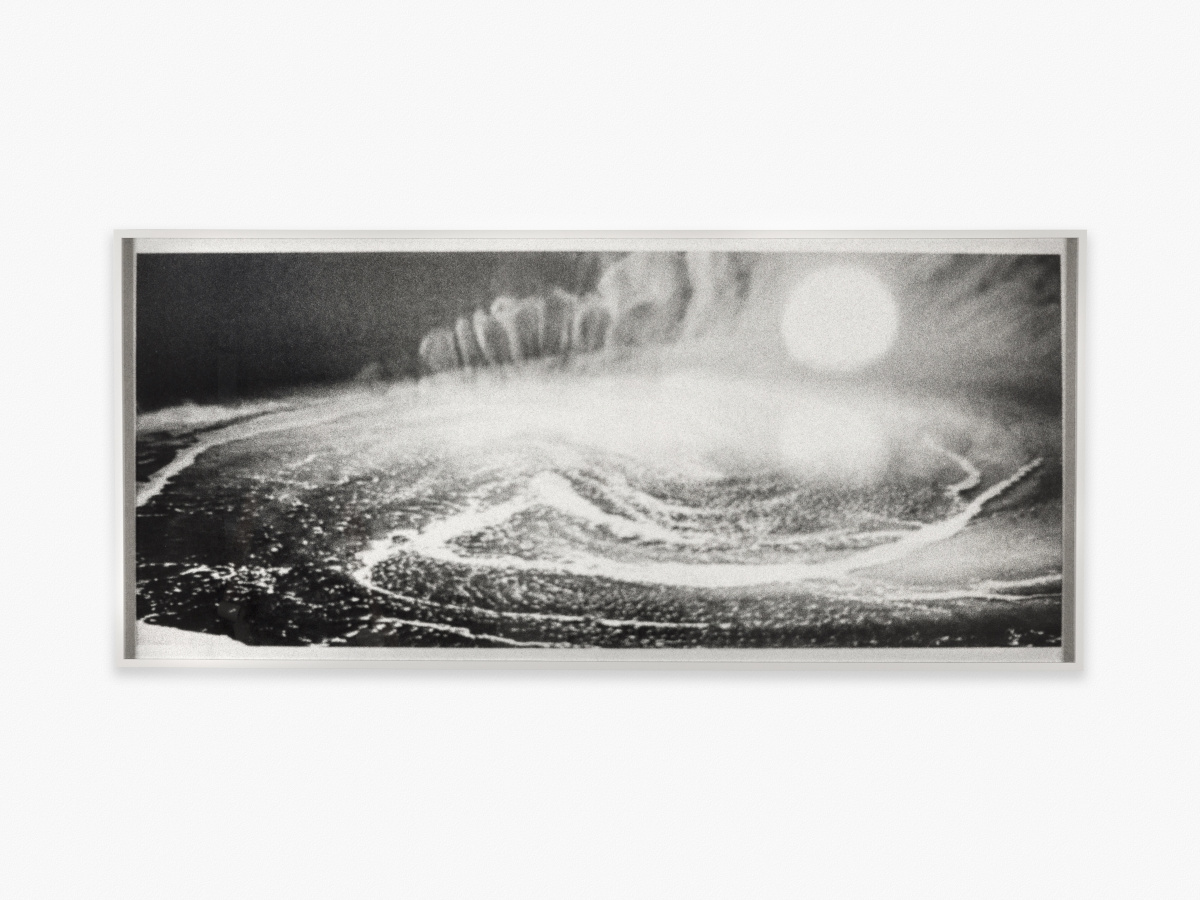

For her Solaris series, Brittany took screenshots from Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Solaris and photographed them onto 35mmx film at high speeds, a process which accentuates the silver grain of the image. Pictured, Solaris Ocean #2 unique silver print by Brittany Nelson. Photo courtesy Evan Jenkins

I entered that class thinking I was receiving a “normal” photography education. Instead I learned these chemistry-based, handmade processes, where you are intimately involved in creating the photo. These handmade techniques bear the record of the artist’s hand. I use huge trays that I’m moving black chemistry around in as the image is developing. My fingerprints are all over the images as they emerge. When these Mars landscapes are developing in my hands, I know it’s the closest I’ll come to touching that planet. I live with these photos. I drag them around. I have a relationship with them.

Has this process helped you develop your own visual language within the art world?

Each project I undertake has its own language. It becomes a bit of a game sometimes. In photographic history, once people figured out that several different substances react to light, like silver nitrate, everyone invented their own weird photo process. There are some that are historically important and others that are bizarre and experimental. No two images look alike. A lot of people use the image as an excuse for the process, but I work backwards.

For example, when I first got into tintype photography, there was a resurgence of tintype portrait studios as a novelty. I thought it was kitschy and annoying. Then I thought, “If I made a tintype, could I do it with conceptual integrity?” I wanted to mess around with the chemical formula because it was so old and unchanged. I tried to reverse engineer what people deemed mistakes, like this silver fogging that happens. It’s so gorgeous but technically considered an error in the process.

Brittany believes at the end of the day, a good print feels like it has its own light and glow. From left, Starbear and Mars Clouds 3 by Brittany Nelson. Photo courtesy Evan Jenkins

Is there a specific look you’re hoping for with these techniques?

I would describe all light sensitive photographic materials as having behaviors. You never fully know how an image will react until it’s poked, stretched, and had its limits tested. I can exert some control over my materials out of an intense familiarity with them, but that is often to my own detriment. Sometimes the chemistry makes better decisions than I do.

I love the process, but I don’t want to fetishize it; it’s a means to an end. Focusing too much on the process can be a trap. Some artists become so obsessed with a particular process that the concept falls apart.

For my Solaris works I used a Fotar horizontal enlarger from the 1950s. It’s gigantic and operates on motorized tracks on the floor. This equipment creates large silver gelatin prints by projecting images onto a wall rather than a table or floor. As far as we know only three of these enlargers remain in working order. When I saw what the equipment could do I immediately thought, “I want to take small negatives and make enormous prints from them.” I really looked at every grain of silver that comprises an image—like individual letters that construct a word.

“The individual dishes that comprise the telescopes look like giant eyeballs. I love those monstrous things,” Brittany says. Pictured, Roll 19, Image 3

For my Face On Mars piece I took the famous image from the Viking Orbiter, taken in 1976, of a rock on Mars that resembles a human face and rephotographed it on very high speed black and white film. I developed the film in chemistry that caused the silver grains to clump together. When this print is enlarged it feels like it’s made of sand.

That’s something I needed to engineer to look a certain way or it wasn’t going to work. It’s dependent on what the project is or the current obsession.

Do you grapple with going between creating an attractive, beautiful image while also sticking to the process?

I usually stay true to the concept needs, but of course I don’t want to show anything that’s not attractive. At the end of the day a good print feels like it has its own light and glow.

“In my Sol 4,999 series, which references photos of the sunrise taken by NASA’s Mars Opportunity rover every morning, you never get the same outcome twice,” Brittany says. “It’s about the repetitiveness of the robot counting those days. I felt I needed to create them forever to balance the weight of those moments.” Pictured, Sunrise 11, halochrome toned gelatin silver photograph by Brittany Nelson

I’m trained as a photographer through and through, but I’d rather be known as a conceptual artist. As a photographer you shoot 100 images to get one good one. That’s what my studio is like—I’ll create a print over and over 50 times to get it right. Some things will take years until I realize, “Yes, this is the right thing.” I’ve been trying to get messier because I tend to be a perfectionist. But the handmade quality of the photograph is really what’s special.

I’ve probably made over 1,000 of my Mordançage pieces and only showed 20. Quality control checks are crucial. In my Sol 4,999 series, which references photos of the sunrise taken by NASA’s Mars Opportunity rover every morning, you never get the same outcome twice. It’s about the repetitiveness of the robot counting those days. I felt I needed to create them forever to balance the weight of those moments.

- And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side, Page 1. Unique gelatin silver photograph

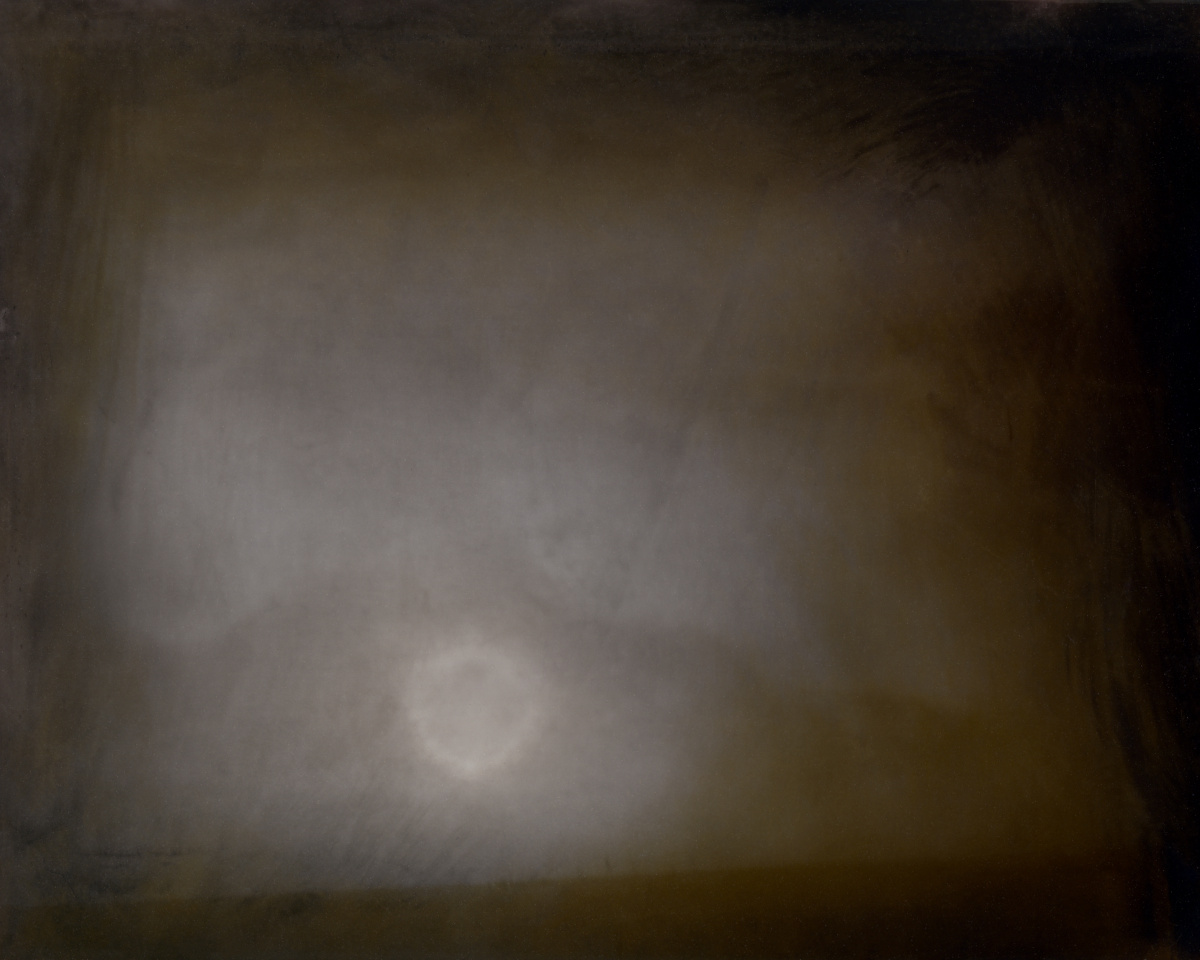

- Mordancage 7. Artwork and photos by Brittany Nelson

Have you had any particularly encouraging moments in your career compared to challenging ones?

I’ve felt both—daily. It’s a constant back and forth. It seems I always receive bad and good news simultaneously. Sometimes I’ll get offered a great show and then get a rejection for something else.

There are a lot of dividing forces in the art world. You can tell when someone is from an entirely different universe. Not that I blame them—people grow up differently and move in the world in different ways. I feel like a space alien all the time.

You never asked me if the aliens are real!

Of course, I was getting to that! Are the aliens real? Is there a layered narrative at play?

Always. So much of the work is about loneliness and distance. That’s why it’s important for me to mix bodies of work. I think of those Mordançage pieces as sci-fi world building, for example. They’re a great way to set a scene because they look like an exoplanet topographic or a weird alien world.

“I live with these photos. I drag them around. I have a relationship with them.”

I’ve also been an artist-in-residence with the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute for about three years, which has been a total dream. There is a network of about 100 astronomers, astrophysicists, and astrobiologists from around the globe, conducting research at various arrays. The Allen Telescope Array at Hat Creek is designed specifically for SETI research. Jill Tarter, the woman responsible for building the array, inspired the character played by Jodie Foster in the movie Contact. She’s been called one of the most influential people in the world by Time magazine. I was invited to her house to interview her last year before my first trip out to the array.

Solaris Window #3, unique gelatin silver print by Brittany Nelson. Photo courtesy Evan Jenkins

The observatory is a four-and-a-half-hour drive from San Francisco, with no cell reception, Wi-Fi, or Bluetooth allowed. It adds to the poetic feeling of the place. Even getting to a grocery store and back without a good sense of direction is tricky, but I love being there. It’s a drastic change, being out in the field photographing, feeling these huge antennas moving around me.

The individual dishes that comprise the telescope look like giant eyeballs. Another colleague described them as a “field of clones.” I love those monstrous things. One time an astronomer I work with, Dr. Wael Farah, programmed the machines to turn and look into the camera lens instead of pointing up at the sky. I just wanted to feel like they were acknowledging me. It’s fascinating to see the dishes from different cardinal directions turning and confronting the camera. These telescopes act as extensions for our senses, observing radio wave data.

Depicting the deserted Martian landscape, Brittany’s Olympia evokes both the nostalgia of hand-created, rather than recorded, bromoil photographs, and the futuristic endeavor to make the barren Mars planet inhabitable.

I think contemplating space is the pinnacle of philosophical inquiry, and there’s a lot of speculation about the first alien we might encounter. I’ve come across so many SETI proposals aimed at “narrowing down the search” for life on other planets, and they’re remarkable. It’s armchair philosophizing, attempting to connect with something beyond us—that sense of looking and longing from afar. It’s filled with unknowns and a desire for connection, which is what my work is about. SETI’s work feels very hopeful to me.

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 12. Subscribe today