Benedict Redgrove and I shake hands. I reassure him that I’ve sanitized, and he does the same. We meet at London’s Barbican—a first for us both since the imposed lockdowns across the UK. He insists on paying for my tea, and he orders a coffee; he holds his motorbike helmet at his hip while we wait for our brews, customarily discussing the side effects of the vaccination, to which I am slightly suffering. He says he found his second to be better.

As we stroll to a quieter location outside we have the view of the Barbican’s concrete exterior at our disposal, plus a swarm of boisterous pigeons circling our every move. A welcome turn from the four walls of our homes—Benedict informs me about his recent relocation from West London to Limehouse, an old warehouse conversion from the ’80s with “swirling patterns” and “awfulness.” He’s joined the clan of pandemic renovators and is more than pleased about his new double-height, live-work studio, despite the incurrent mess. “I’m living amongst cardboard boxes,” he laughs.

Benedict was born near Reading, England and studied at Berkshire College of Art and Design before a career in graphics. Working at various agencies, his creative director once said to him, “You’re a better photographer than designer.”

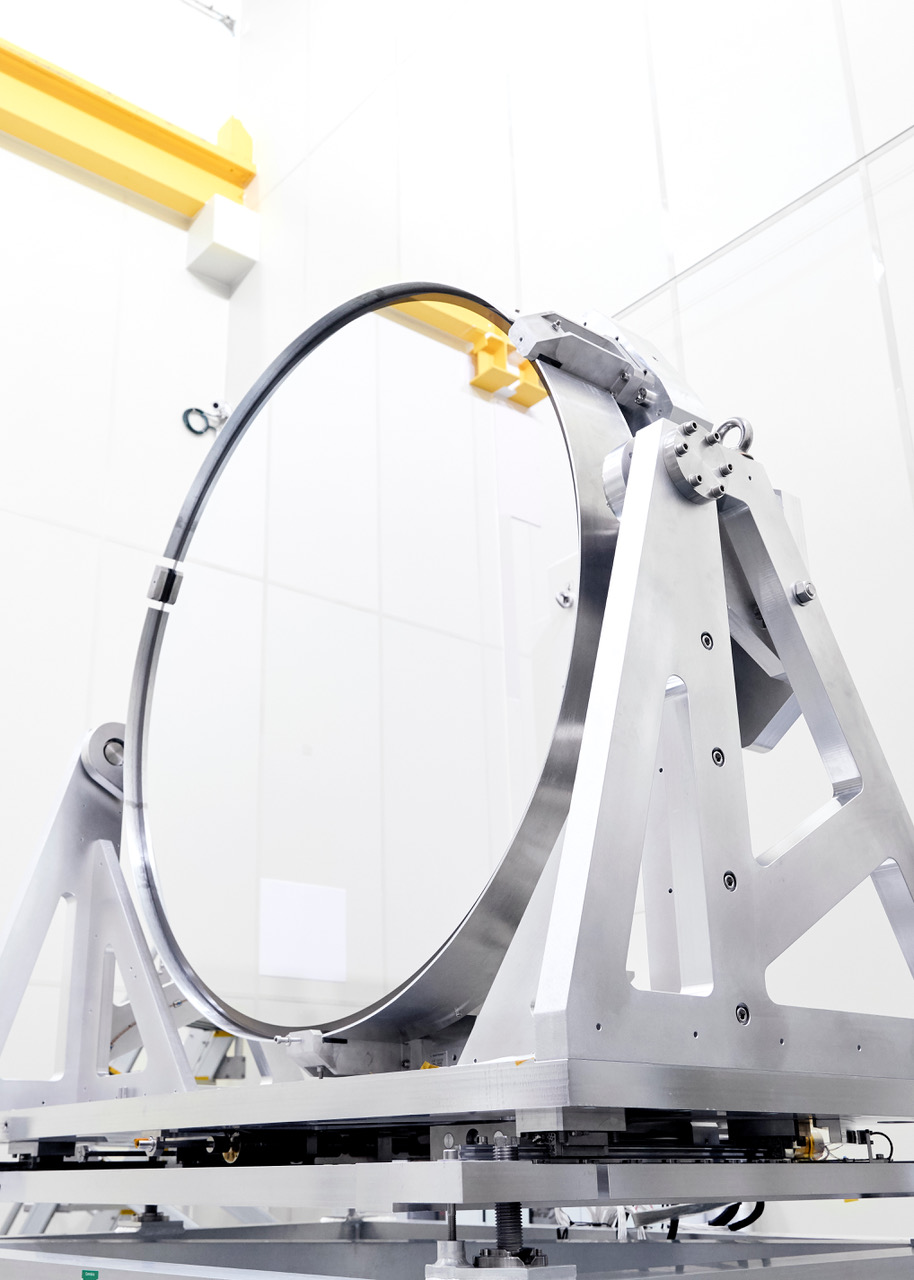

- Benedict is currently working on Euclid for the European Space Agency and Airbus. He hopes projects like these will make science more accessible to everyone. “I’m trying to evoke a feeling in the viewer.” Courtesy of Benedict Redgrove

Spurred on to shoot on the weekends, Benedict started to carve out his photographic vision—one that details his lifelong fascination with space and innovation. He’s received many awards for his work lensing spacecrafts, telescopes, and celestial objects, building on his impressive roster of clients like Lockheed Martin Skunk Works, the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defence, the Royal Air Force, and NASA. “As a kid the space program was something I could firmly believe in,” he says. “I had a tempestuous father who wasn’t really the best person.” He turned toward astronauts and racing drivers as his heroes; they taught him many lessons about hard work and exploration.

His portfolio is meticulous, devoid of any background noise and mess—just like the clothes (a smart, costly looking leather jacket) he wears on the day we meet. He seems trustworthy; perhaps this is why he gains access to heavily restricted organizations like NASA, which took him around four-and-a-half years to get into for a past project. “It’s an involved process and it’s very expensive; it takes a lot of time and money,” he says. “Anyone they’re inviting into that area needs to be helping promote what they do and needs to do some work they respect.”

- Courtesy of Benedict Redgrove

- Space Shuttle Atlantis overhead detail showing cockpit and reaction control engines, John F. Kennedy Space Centre Florida. Courtesy of Benedict Redgrove

As time went on, Benedict amassed a notable collection in the field of space. He gained recognition and trust, paving the way for his most recent ongoing project, “Euclid,” a commission comprising film and pictures devised for the European Space Agency and Airbus. The project arose after his friend, a film composer, asked if he’d wanted to work together. “It started off as a small project, but it’s grown into a film and experiential event we’re trying to work on.”

A pigeon interrupts. “That’s Duncan, my agent,” Benedict laughs, before turning back to the conversation. He explains how the European Space Agency agreed to let the duo proceed with the shoot, even if they were a bit suspicious at the time. This changed once the organization knew more about what they were planning: a scientific documentation of a telescope that, once launched next year, will be able to scan the universe “up and down” for dark matter and energy, “the bits you can’t see in space that force everything to be where they are.”

These “head-exploding” inventions—as Benedict calls them—are what he lives for. He knows all too well that science and physics can be hard to understand for the masses. Elitism in science is something he strives to address and break down through his work, achieved through a minimalist palette paired with crops and zooms of scientific equipment.

- Courtesy of Benedict Redgrove

- Courtesy of Benedict Redgrove

Our conversation steers toward the wider picture, and the Barbican suddenly starts to feel a lot smaller. Benedict is excited by the thought of our minuscule existence. “Our Milky Way is completely inconsequential. If it all disappeared nothing’s really going to happen to the universe. Then you start to realize that we are extremely lucky; you and I are very lucky to be talking to each other right now and living in a world where we function and we’re conscious, sentient beings.”

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 07 with the headline “Benedict Redgrove.” Subscribe today.