I catch Anton Alvarez in a moment of calm in his Stockholm apartment. His place looks like a gallery—neutral spaces peppered with colorful furniture, art, and objects; some pieces are his own and others are collected from fellow artists and friends he swaps with. “It’s a little bit of a small collection I’m trying to build,” he says, spinning the camera around to reveal a chunky, cobalt blue shelving unit he created in 2009 while at Konstfack, Sweden’s largest university for arts. Behind him a piece of timber wrapped in multi-colored threads hangs on the wall. This was made using his Thread Wrapping Machine, which he developed in 2012 and used to create a critically acclaimed series of mummified furniture pieces that were held together by hundreds of meters of colorful thread and glue.

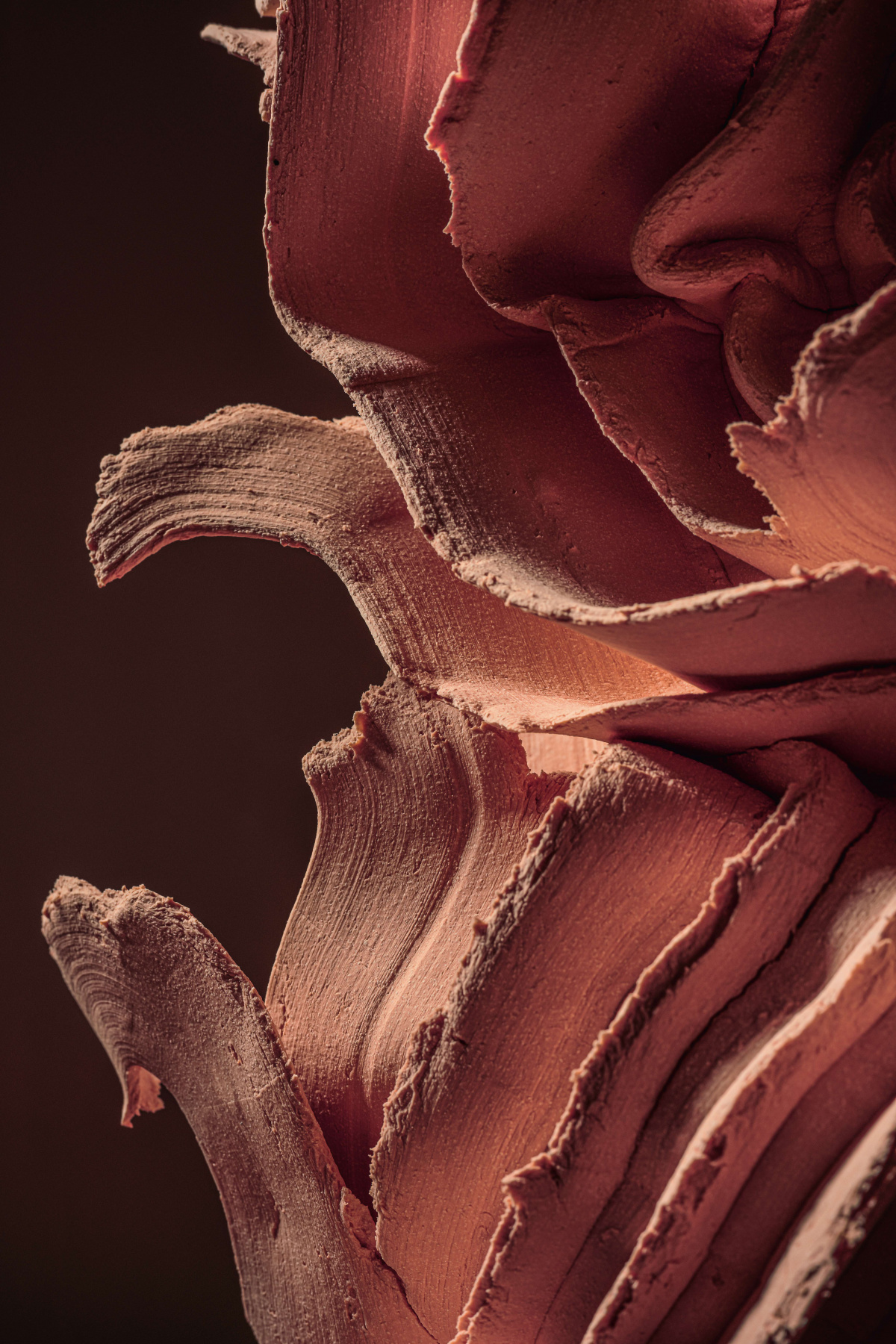

Now Anton is working primarily with ceramics and a self-constructed, 10-tonne, 50-centimeter-wide ceramic press called “The Extruder” that squeezes out tactile, totem-like sculptures he glazes or spray paints in tantalizing colors. In London he has produced and installed six of these large works in the marble lobby of a high-rise. Sitting alien-like in their surroundings, he says the stacked works drew curious stares from the area’s businesspeople. “There were people walking along the street using the windows as a mirror to check their hair or something, then suddenly they saw something that was unusual. I love that,” he smiles.

Called “The Remnants,” the project marks a development in Anton’s practice that sees him grinding down old sculptures and using reformed clay to create new works. He plans to repeat the process by grinding the sculptures down again to reuse the clay for future exhibits.

In Italy Anton is working on a new series of extruded bronze pieces made using a traditional lost-wax casting process. Instead of ceramic, wax is placed inside the extruder machine, which is suspended from the ceiling and powered by an electric motor. The wax is pushed through different molds before plunging into a pool of cold water and cast in bronze. While art in its own right, the bronze forms can also be interpreted as furniture—stools, vessels, trays, and benches, for example. “It’s the feeling of being able to surprise myself that gives me energy,” he says. “It’s the knowledge that something out of the ordinary within my process might happen if I do this or try this or this.”

- “050211358,” 2021. Courtesy of Studio Anton Alvarez

- “050211358,” 2021. Courtesy of Studio Anton Alvarez

- “504211739,” 2021. Courtesy of Studio Anton Alvarez

- “1705211932,” 2021. Courtesy of Studio Anton Alvarez

- “1205211514,” 2021. Courtesy of Studio Anton Alvarez

- “1205211514,” 2021. Courtesy of Studio Anton Alvarez

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 08 with the headline “Anton Alvarez.” Subscribe today.