Andy Gent’s workshop is an ode to his past films, a library filled with life-size Isle of Dogs sculpts, illustrations for characters from Corpse Bride and Fantastic Mr. Fox, and miniature molded busts and limbs lining shelves on every wall. As the owner of Arch Model Studio in London, Andy is the master puppet maker, sculptor for stop-motion animation films and advertisements, and on a first-name basis with beloved filmmaker Wes Anderson.

To create one of his elaborate puppets, Andy and his team start with a mechanical skeleton that can move in any way its character needs to, from scratching to dancing, as inserted gels support movement. Silicone is applied to resemble skin, real hair or fur is added, painted eyes, and resin teeth. Then comes the hours of set design and sewing miniature costumes before animators position the puppets in a series of whimsical, wonderful frames.

Andy and his team—regularly 12 people, but he’s recruited up to 60 for large projects—modeled more than 1,000 various-sized puppets for Isle of Dogs, working for 34 months to create characters for the 90-minute movie. But that doesn’t even begin to describe the depth of Andy’s 25-year dedication to his treasured craft and the stop-motion industry.

A finished cat puppet is posed on a couch.

I understand you started tinkering as a kid because your dad was making cabinets. What was that time like?

I started making little mechanical toys, which was a lot of fun for me as a kid. It became more and more elaborate. Friends were involved with war gaming and model making and Dungeons & Dragons. There are all these kinds of things floating around in my childhood. I started to sculpt things to amend items that were boring, then elaborating and making my own tiny sculptures, then scenery for it all. It became quite addictive at that level between friends, not thinking there was a career in it. It was for the sheer fun of it.

There was an amazing series about animation called Four-Mations that Channel 4 did here. On Friday nights they would showcase a new film … It was a eureka moment where you went, “They actually get to do this during the day, and they get paid to do it.” I thought, “I’d love to make stop-motion because all the armatures are attracted by their own mechanisms, but these puppets can run around and tell stories on their own” … I then started to make two short films at university, which were good enough to get me onto the freelance ladder when I left.

I left university on a Friday, and I was given a runners job on Monday on a stop-motion commercial. By the end of the week I’d been asked if I could have done some animation. “Could you background animate a cow in a barber shop?” Which I did. Then they said, “Actually, come in next week.” This “come in next week” lasted for two years … Anywhere that had any work, I would go. I would jump on the opportunity and keep expanding what I could do until, eventually, a film came in, which was Corpse Bride. I was in a lucky position that I had worked for many different places in all parts of the stop-motion world in the UK.

The whole experience of working on a feature film was the bee’s knees. Once you’ve worked on a stop-motion feature film, it’s a pretty amazing, addictive, fabulous experience. It still makes me smile now. We sat around going, “Wow, we got to work on the last stop-motion feature that’s ever going to get made,” because computer animation was coming to the scene. Now we laugh about that.

Each puppet is carefully positioned during a shoot.

So you created a studio space after you worked on Corpse Bride?

It started off as a very little studio space. People were asking me if I could run small runs of things: commercials and short films. We were doing all that. We were doing sets, puppets, puppet rigging, a whole matter of things. It carried on being quite varied. I got asked to do a film in Switzerland called Max & Co, to run the puppet department, which was the first real step up into leading on a puppet show. I’d done several hundred commercials by then, so I’d gotten a good breadth of experience.

What’s your process for recruiting a workshop team? How much do you collaborate with them?

When you get to a large job, it’s a big collaboration. We’d like to do everything on our own. If you’re a puppet maker, it’s nice to do every single thing. But once you’ve got dozens of puppets to make, sets, and a time scale, you need a big team of people to do it all. Recruiting for that amount, after over 20 years of working in different departments and different places, you meet a lot of amazing, skilled, talented people. You distill down to the ones you enjoy working with.

I find that, even if the person’s not necessarily the best person—they need to have quite a lot of skill and talent to get on the radar—it’s whether they get on well with the rest of the workshop. After 20-odd years working together, we’re protective over keeping that good balance of people in the shop. Enthusiasm and politeness go an awful long way. If we all get on, there’s experience to be shared and given to new members of the team. If everybody likes them, they’ll seed them with all of the wisdom and experience of everyone who’s gone before.

- Andy’s dog Charlie is the studio’s mascot and was the inspiration for many of the Isle of Dogs characters.

- Armatures, the one above of Atari from Isle of Dogs, are the basis for all of a puppet’s movements.

What does a typical day look like for you?

To be honest with you, the whole thing revolves around my chocolate Labrador. It’s not about me. He was a puppy on Fantastic Mr. Fox. He’s 10 now. We’ll get up and walk, then we’ll come into the workshop. He’s now getting a little older. Everybody waits for me to get in at 8am. I’ll brief anybody, if there are any jobs that are ongoing. We’ll have a look at anything that was finished late the night before. We’ll start everything within the sculpting room. We’ll look at any sculpts ongoing, check the emails for anything that’s feedback on sculpts we’ve been working on, and then go from department to department. I like to make sure it runs in a nice way.

How do you balance work and personal life?

Badly would be the honest answer to that … It takes up an awful lot of time. You have to learn to delegate. I think it’s one of the biggest, most important things to try and keep a balance. It goes back to one of your earlier questions about the team. You need that around you to alleviate some of the pressures of the whole workshop. But it’s difficult to resist a Labrador who has his nose pushed against you, whining, saying it’s time to go home. At least you have to go out of the workshop for an hour or so.

Related | Art Director Victoria Bee Makes Oversize Paper Props That Make a Scene

It is tricky because it’s a long format kind of work. You have to pace yourself. We might be on a project for three years. It does seem like, when you’re on a film, you’re sort of linked to a lot of things happening. You just get on. Out of a team of 50 to 60 people, there might be 50 characters going through the workshop at that time. Your mind is completely focused on all the processes and all the things that are happening. I’ve got behind me in the office a magnetized, steel board with all the characters on it from another film. I think once you’ve put the plan down, you have a little bit of your time back. Without having some sort of clear plan, I don’t think you’d ever leave the place. You’d be petrified. To keep a balance, you have to plan things out carefully, delegate well, and make sure you’ve got a dog that needs to go home.

Puppets like Conor McGregor, who was used in a recent Reebok commercial, go through several edits before they’re finished.

Do you ever imagine doing something else?

We often think about doing other work (laughs). I think that’s dependent on the project and the time scale we’ve landed ourselves with. But that’s a pressure thing. I absolutely love this job. I love making puppets. I love seeing things from a line on a script to it tapping back on the screen and running around of its own volition. I think it’s the most amazing experience. It’s a magical experience, when you’ve created something, and it’s moving around and you’ve stopped thinking of every single process and all the bits that went into it all.

It’s so addictive. It’d be difficult to find something better. But there are times in the wee hours of the morning—having done a full day, and probably several days like that beforehand because you’re trying to get something done—and for a very tight schedule where you’re like, “This is absolutely crazy that we’re working like this.” There’s an awful lot of late hours spent to get something ready so it’s on set for an animator … That’s when you question (laughs). But for some reason, we keep going back to it. Obviously, we like it.

- Andy and his team created models of Conor McGregor for a Reebok commercial.

- The Reebok commercial also included a “demonic” clown and several other wacky characters.

What’s the difference between creating puppets for movies and advertisements?

The time scale’s a massive difference, to start with. For Reebok and Honest Tea, we had to go from first discussion to shooting in a very few weeks: five, six, seven weeks … There are more chances to shine and enjoy and to design and influence it on a film. It’s a more enjoyable process. The pressure is different. It’s nice that you can advise and have time to consider. Sometimes you have to make shortcuts on a commercial. You’re very much thinking of what’s going to be seen. With a feature film, you have no idea so everything has to be very carefully considered and finished. If you’re a maker, you want to make everything really, really well. If you’re not sure if it’s going to be seen, you’ll still endeavor in case an act later does something with it.

We often say it’s like steering an oil tanker on a feature film. It’s a massive ol’ thing, but it doesn’t turn very quickly, so you don’t want to set it on the wrong course. Whereas commercials are a bit more like speedboats.

Andy’s studio space held the miniature set for an Honest Tea commercial.

When you’re creating puppets for films, how do you go about reflecting their character?

What have they got to achieve? Do they fly? Have they got wings? Have they got fur? Are they wet? There’s a whole matter of things that could come up in a description that will heavily influence how you approach the design and how many [you make] of them … We had several scales on Isle of Dogs, and so you’re also thinking, “I’ve got to make the half-scale, quarter-scale, teeny-tiny scales. How can we make that work? Is it going to be a wire armature? Can it have a ball-and-socket armature? Is it real hair?” There are so many considerations. Wes actually said once about making a stop-motion film, “It’s breathtaking the amount of decisions you have to make just to get through a day.” It’s the same with designing them.

You’re constantly watching people, thinking, “I really like this face, I really like these eyes, I really like that hair.” You build it in. With dog walking a lot, you’ll meet up with dog walkers. You’re exposed to a lot of people and their pooches. So you’re like, “Wow, that’s an amazing ear or how that hair curls.” You’re watching all the time. You’re building all of these experiences. On a film, it’s like if you own a bank account. You’ve been putting things into the bank account, all these things you’ve seen or witnessed or drawn or made in the past. But when you’re on a film, you’re constantly cashing them out. The films take a lot from you. And then you need to go away and enjoy new things, see new exhibitions, and go and try and be away from it all to build up a fresh bank account of experiences to cash out next time.

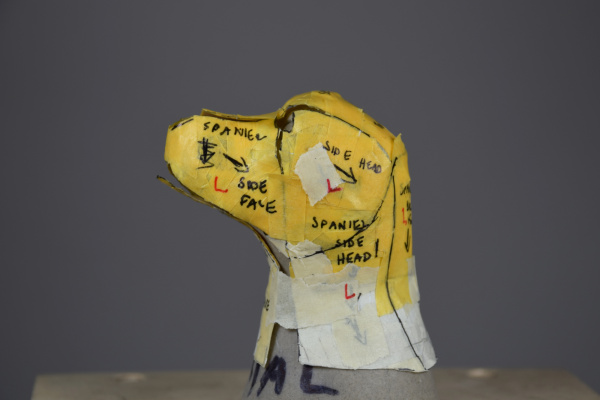

The Isle of Dogs characters went through several stages and edits.

How do you know when you’re done with a puppet?

They’re never really finished (laughs) … Wes is very free. He’ll change and he’ll adapt, and he’ll evolve quite quickly during the course of the film. It’s not set in stone at the beginning as to what it will be at the end. You have to think on your feet and move.

[On Isle of Dogs, Wes had] given me some photos of street dogs that he liked the look of, but there were no drawings. It was simply like, “Let’s start sculpting” … He picked bits and pieces he liked and suggested, “Can we try a bit of this? Can we try a bit of that?” Then we’d follow his line that he liked from all the things we’d done.

Once you’ve built a puppet, there’s a constant series of things that happen to it. It’s evolving. You’re fixing things and changing things, trying to make it better all the time. It’s your best guess with the information you have when you build it. As it’s given to an animator, they’ll find little bits: “It’d be great if we could just do this, and it will be better.” They come back and we carry on working on them and delicately, like Frankenstein’s workshop, take them apart and put them back together again to see if they’ve made an improvement.

What have you learned from working with Wes Anderson, and how has your relationship changed since your first film together?

The very first film, on [Fantastic Mr.] Fox, I came into that feeling I knew quite a lot about stop-motion animation. I’d done quite a lot by then. Everybody had been going down a path of trying to make it a very slick, CG-like level of smoothness. Then we came across Wes, who had a whole different idea of how he wanted it to look: more pre-video assist and looser and freer … We had to recalibrate to work with him on that. It was quite challenging from the maker’s point of view. Everybody was delighted with the end result. We didn’t know quite where we were going to go. It was a real adventure. Then we worked together again on The Grand Budapest Hotel, just a little sequence.

One of the things I would say about Wes is he likes to work with familiar people. He feels comfortable. He’ll go back to you. That’s quite a nice feeling because there’s a lot of trust there. You have to earn your stripes. You do one film and then, if he comes back to you for a second one, it’s a lot easier communication because there’s familiarity and there’s confidence. By the time we got to Isle of Dogs, it was a different experience. It feels much more trusted and confident and more like you’re in the family … He adapts things and changes things. That’s what’s really pleasant about working with him. You’ll see an opportunity, and it’ll evolve with him. He’s very good. It’s a good adventure to work with him on a film.

Above, a mold from Isle of Dogs.

When you said he uses you because he trusts you, do you carry that in hiring your own team?

Always, yes. As I mentioned before, I have people I work with who I’ve taken with me to various places I’ve worked around the world. You know each other’s shorthands. We all know each other’s strengths and weaknesses. It’s a good way of learning together and evolving together. You have a little winning circle then of people that you go, “I’ll ask them because they’ll probably have a good idea on that one.” They’ll do the same to you. You keep pushing each other’s boundaries in a good way. You don’t want to feel challenged by it. You want to feel like everybody’s throwing good ideas forward and feels confident.

What’s next for you?

It’s the longest-winded way of doing this I’ve ever known anybody to do, but I’ve now got a model making studio and managed to set up a film studio, a set-building area. I’m hoping this year to start my short animated film. I’m long overdue in making my own. That’s the endeavor for the workshop this year: Steer it into helping me make my own short film. It’s written and keyboarded and I’ve got some of the early sculpt-work out of the way already.

Good luck with that. It sounds wonderful.

Thank you. You need lots of luck for that.

Photos courtesy of Arch Model Studio