Andy Coolquitt embraces the elusive and often indefinable nature of his art. Walking through his spacious East Austin yard on an unusually rainy summer day, there’s an organized chaos to the layout and feel of the area. With his girlfriend, photography-based conceptual artist Susan Scafati, we stroll around the huge pecan trees and three large, hand-built, shack-like structures where Andy lives and practices. The constructions are Andy’s graduate thesis project that began in 1994 and never ended. It’s a work of sculpture and performance art mixed with a living space, studio, gallery, and whatever else he may want to use it for. Not knowing what to call this place is exactly the point.

Colorful materials and scraps collected over the years make up the hodge-podge of structures, with zany details Andy proudly points out during our tour. The telephone poles supporting the walls of his studio were gifted to him by University of Texas frat boys, the merry-go-round parts that make up the staircase were left to him by a friend, and eccentric trinkets scavenged from all over the city are scattered throughout the yard. Decorating the exterior of the house and kitchen are paintings commemorating what one can assume are the dead pets that formerly resided there. Among this grand display of oddball designs, Andy himself is refreshingly unassuming and amiable.

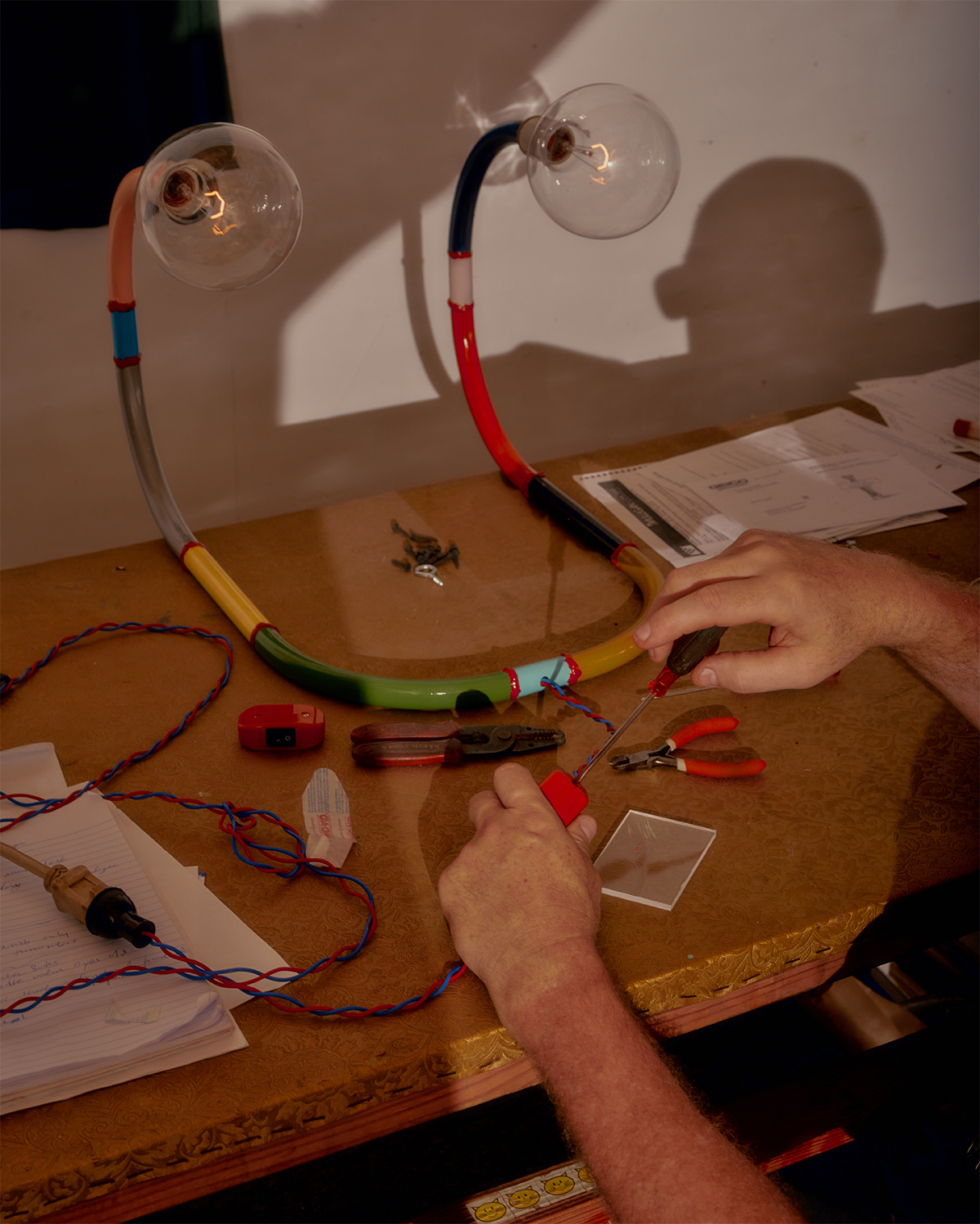

- Andy’s exhibitions like “Attainable Excellence” contain myriad objects, including lights he designed from his home studio.

- Visitors to Andy’s Place become part of the artist’s work, if only for a moment, as they’re quite literally surrounded by works in progress. For Andy, life is art.

This famed installation is now called “Andy’s Place,” despite his reluctance to name it. “I think we’re brainwashed to think art is an object for sale, and I didn’t want to commodify my life by naming it,” he says. For Andy art is a living, breathing process—something intrinsically linked to the artist as a person and their life. Nothing could be better evidence of his philosophy than the area itself. It feels lived in, an area that’s undergone a natural aging process. He shrugs off any labels for himself or the things he makes. Everything is amorphous and nothing is exactly one thing.

This soft rebellion has always been a part of Andy’s practice. Raised in Dallas, the artist initially moved to Austin for undergrad at UT. He left the state for a brief stint in LA but moved back shortly to work at Texas School for the Blind from 1990 to 1994. Observing the students there increased his awareness of how psychologically impactful the relationship can be between our bodies and pieces of furniture or the structure of a room. He then returned to grad school at UT, and his fascination with people and spaces merged with an interest in the concept of life art, which mandates that the life one constructs is the work of art, and objects come out of that. This crucial combination became the basis of Andy’s work and led him to start building Andy’s Place for the sculpture department.

“My work was getting more and more about how things worked in domestic situations rather than institutions or public spaces. It became clear at a point that I could do all these experiments in an art gallery or an art museum, but it would only be existing on a theoretical level. To do a real house as a grad student, not in architecture but in art, to make a real house in the real world and deal with real problems is what needed to happen.”

“I think we’re brainwashed to think art is an object for sale.”

Today Andy continues to exercise this way of thinking across projects. One particularly intriguing and involved venture is an architecture consultation business and art project called The Center for the Identification of Architectural Micro-Aggressions, Molestations, and Assailments, or C.I.A. MAMA. In this he critiques the architectural or interior design of a constructed space, offering a fresh set of eyes to notice the door that opens in a wonky manner or the inconveniently placed chair. The idea is to give suggestions to make spaces more functional—and ultimately to make life easier. “It began as kind of a joke but not really. Like everything I do.”

We sit together in the newest part of the project—a tall open-air structure at the back end of the yard, accompanied by his outdoor cat Willy, who periodically struts in to sniff around the display and snuggle with Andy. Andy began building in 1998 but left it unfinished as other pursuits came up. For years it stood as a wall-less shed to hold his junk, until November 2021 when he realized its potential as a makeshift photography space. It evolved into a building with four walls and now functions as a studio space for Andy as well as the gallery DUSTY that he and Susan created together.

Andy and Susan create new sculptures and begin new projects constantly, simultaneously working and simply living.

As Andy and Susan discuss their endeavors, their shared spontaneity and hands-on approach to art is striking. The pair recounts a recent trip they took in West Texas, how they fell in love with the Sotol plants and ended up taking some dead ones home with them. They began collaborating on a lofty mixed-media sculpture combining a Sotol plant and plexiglass. They bring in their sample—a stack of plexiglass boxes containing chopped parts of the tall stock that results in a reimagination of the plant within plastic, toying with the relationship between artificial and real. “We like plucking objects out of our everyday life and thinking about how we want to shape them,” Susan says.

The rain calms down and we talk about living in Austin. Andy shares stories about summers in the ’90s before he got AC, how he would jump into Barton Springs at 9pm, bike home, and lay in front of a fan to fall asleep. As he’s telling me this he and Susan are tweaking the materials of their sculpture, examining the lighting from different perspectives and shooing Willy away from stepping on it.

The amorphous structure of their work/home life grows clearer. I ask in which space they primarily practice, how they schedule their days, if they play music to get in a zone. “They’re great questions because the idea of the artist in their studio separated from everything else in their life just doesn’t exist in our world,” Andy says. “We work while we’re making dinner, when we have company over, all the time really.”

Exploring “Andy’s Place” is an adventure in itself, as art, found objects, and works in progress greet visitors at every turn.

- Andy shrugs off any labels for himself or the things he makes. Everything is amorphous and nothing is exactly one thing.

- Andy has spent decades collecting colorful materials and scraps to create his dream worlds.

“It became clear at a point that I could do all these experiments in an art gallery or an art museum, but it would only be existing on a theoretical level,” Andy says. “To do a real house as a grad student, not in architecture but in art, to make a real house in the real world and deal with real problems is what needed to happen.” Andy’s Place has only grown since.