Yrsa Daley-Ward is a British writer, actor, and model, known for her powerful poetry and prose that explores themes of identity, mental health, and sexuality. She has collaborated with Beyoncé, contributing to the visual album Black Is King, and her acclaimed works include the poetry collections Bone and The Terrible, the latter of which won the PEN Ackerley Prize.

Chris Force: I’m curious about the bravery it takes to consider yourself a poet. The idea of writing my most vulnerable feelings in fragmented, unorthodox ways and sharing them with the world to put food on my table is unimaginable.

Yrsa Daley-Ward: I don’t know that it does. You have to become well-versed in doing a bunch of stuff. I’m from a Jamaican immigrant mother who knew what it was like to work two jobs and also be studying. She was studying for her degree right up until 10 years before she died. She was always striving.

I have had to adopt a mentality of layering one thing over the other over the other. I’m acting, I’m speaking somewhere, I’m writing my book, and I’m thinking of pitching another one—and that is the way. It’s impossible for me to sit and wait for the muse to strike. I don’t have that luxury. Whether it’s modeling or acting, I have to become good at doing a lot of things. When I’m flying somewhere I’m also writing or taking a commission.

On the other hand I’ve also created great pockets of peace I have to be intentional about. I spend the majority of my time by myself. I’m a poet, and yes, this is how I live, but it’s also a bunch of other things. It’s working with brands. It’s also doing things I can fit words around; you have to get creative with it.

Tell me about these pockets of peace.

As I get older I can’t override my body. Sometimes I have to after a long flight, but I really try to be inside of my body. I’m not someone who will force myself to be super social. I don’t know how to do that anyway; I’m more of a one-on-one person. I meditate and I make sure I take care of myself. Sometimes it’s as simple as sleeping a lot. I take time to rest and don’t force myself to be around what drains me.

Are you ever hard on yourself to be better—or to be as successful as your peers? To make more money or be more financially successful?

You can’t compare yourself to someone else. Everyone is on a totally different trajectory and comes from a different background, so I don’t have those fears. I love when people are brilliant. That energizes me. I don’t want to have done my best work. My best work should always be this thing I’m aiming toward.

As far as making more money, of course. As a poet I want to make sure I have some stability. This fear of not having enough, or not knowing how much you’re going to make, seems to be part of the artist’s journey. It completely limits your creativity because you’re out worrying about that. It isn’t a peaceful place to be in.

THE MIDDLE FINGER POEM

By Yrsa Daley-Ward

You say that I don’t seem myself.

These days are long and revealing,

so every time I see one through, I grin.

Every time I make it home, I dance.

Every time I’m up again after being down, down, down;

I’m beating the odds.

Every time I don’t give up,

it’s worthy of celebration. Every time I write a poem,

it’s a bloody miracle. Of course, the me you knew before

is less available. She is keeping herself awake.

She is salt bathing and

forest walking and turning off her phone.

She is learning herself

and teaching herself piano. See the headlines.

See the persistent, awful news,

see the updates no one wants to hear or know about.

See the numbers – have you seen the numbers?

See the terrorists they will never call terrorists.

See the telling dark of the system.

See my beautiful body; offensive. My gleaming skin;

a problem. Who can still be themselves these days?

Isn’t the self a fine art composite,

an odd mosaic

a strange and growing story?

I no longer have time to lie to you.

Why do you think the cultural understanding or acceptance of poetry hasn’t evolved much despite social media poems and hip-hop being so massively popular?

I agree, I don’t think poetry is considered very mainstream. It’s cool in some places but not all. If you think of Kendrick Lamar, he won the Pulitzer Prize. Music has an entry point for everybody. It’s all in how it’s captured. I blame the school system as well for teaching us closed-shop poetry that people don’t understand instead of accessible poetry. When poets make very accessible work, people like it.

I found your books very accessible, but I’m sure there were layers or levels of your work I wasn’t picking up on.

I doubt it. It’s all there to see. I don’t think in that way. I don’t write in that way. What you see is what’s on the page.

Do you ever think about how you might bring your talents and work to different audiences?

One thing I like to do is perform my poetry with musicians. Sometimes it’s acoustic, sometimes it’s electronic music. Sometimes I just put the words over a beat and create different ways of letting the work travel.

I imagine you don’t have the opportunity to digest or live with the work you’re publishing in your newsletter the same way you do when you’re writing a book. It seems so personal and intimate at times. Your thoughts must be flying off your fingers and out to the world. Has that been different from the process of writing your books?

I’m a patient-impatient person. I’m patient on the face of it; I’m not someone who reads into something after it’s been done. The newsletter satisfies how I feel in the moment. I freewrite and put it out there. It doesn’t need to be perfect. It goes into people’s inboxes, and they can read it or not read it. I try not to obsess over it. It’s different than printed matter, which takes about two years from start to finish. For me that is not the most enjoyable process, to be honest. It’s lovely to have the “click” and the pleasure of having it out in the newsletter. The thing isn’t even edited; it’s just a moment, and then it’s gone, like the weeks. They just go. I don’t see the point of worrying about this stuff in the bigger scheme of things. I just want to share something real.

Have you always had that confidence? Or is that something you had to learn?

I don’t know if it’s confidence, it’s just not where I place value. I love writing. I know that it’s imperfect; I’m just learning in public. Maybe I’ll keep getting better support, or maybe I’ll keep strengthening. I’m happy to show that process.

You have worked on some major projects, most famously with Beyoncé. What did you learn through that level of collaboration?

I’m excited by people who are married to their craft and care about every aspect of it. It’s something I aspire to—that kind of attention to detail. Beyoncé has that, and it’s so evident. She’s there for every decision that gets made. When you’re up close to that you can’t help but want to be even more of yourself. It’s easy to go into spaces where you think that’s happening, but it’s not; it’s actually loads of middlemen. The whole thing happened so quickly as well. Not the work itself, but from hearing I was going to be doing that, to being in LA and doing it—it felt like two minutes. It was a great learning experience.

Who else are you reading right now?

I love Jeanette Winterson because of the genre-bending aspect of it. I’m reading one of my favorite books by her again called Written on the Body. I’m also re-listening to this book by Annie Dillard called Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, which when I’m traveling helps me sleep. The imagery is so dense, it helps me drop into myself. And I’m reading Roald Dahl.

That’s unexpected. How did that end up on your shelf?

As a kid it was the first time I had seen someone embed poetry into a story and make it better. I like when things fizz and melt into each other. I think it’s interesting. Roald Dahl was one of the first people I came across who did that.

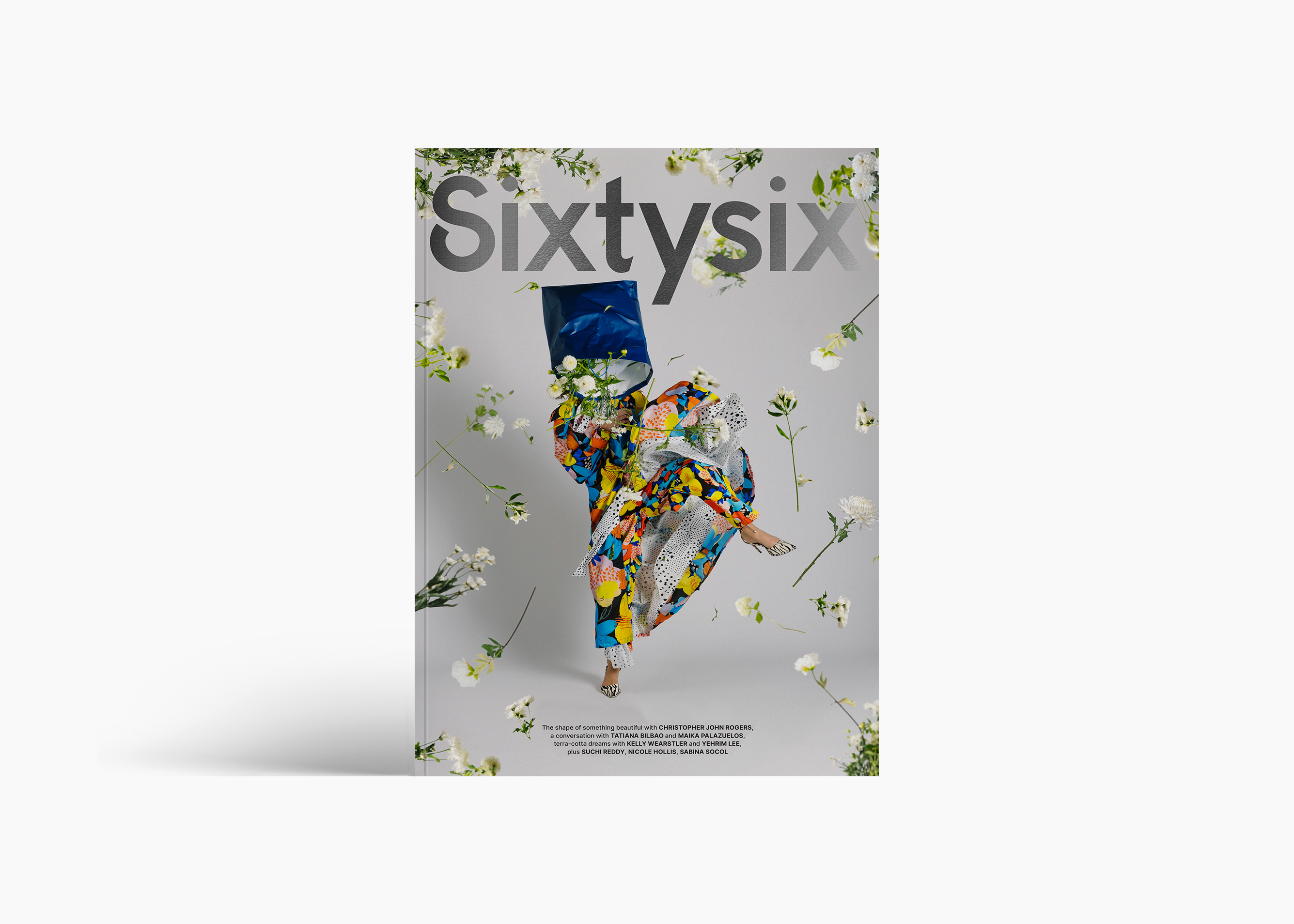

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 12. Subscribe today