In corresponding with Yasuhide Yokoi and looking over his wide-ranging designs, you can’t help but let your inner techno-utopian swell a bit. He’s a 3D-printer evangelist who’s used his digital wares to develop everything from office accessories to painstakingly complex autonomous electric vehicles. An industrial designer with Kabuku, a 3D-printing and digital manufacturing startup, he’s collaborated with the likes of Honda and Autodesk. His designs hit on everything from mass-scale, user-friendly ubiquity (he designed cameras for Nikon for seven years) to highly niche and future-forward (driverless mail delivery vehicles, anyone?).

We recently caught up with Yasuhide to talk about the digital manufacturing revolution, designing for different global markets, the tools he can’t live without, and how the “messy parts” of the design process are the most important.

Can you walk me through two of your autonomous electric vehicle designs, the Tier IV Milee and Logiee? How does designing for personal transportation vehicles differ from logistical task vehicles? Are those available to purchase, and who do you see as the target audience? Also, is the Postee currently in use by any postal services?

First of all, as basic information, Tier IV is a software company—one of the leading industrial startups—for autonomous mobility. I’ve been supporting and leading their hardware design since the early stages. The Milee is an autonomous electric vehicle aimed to fit a specific need in the driverless taxi business. Especially in the mobility industry, there’s a blank field called “last one mile,” where a distance is too short for current cars and other transportation to cover—the distance between a bus stop and your home, for instance. The Milee is designed to fit that gap.

The autonomous, electric Tier IV Milee is designed for short-range travel. The look intentionally stands apart from traditional automotive design to evoke ‘the new era of mobility.’ COURTESY OF YASUHIDE YOKOI.

On the other hand, the Logiee is dedicated to the logistics industry. Even though the industry is defined under the single term “logistics,” designing mobilities for that field is a bit tricky because there are many different niches, plus specific criteria depending on each situation. For example, the mobility vehicles for an airport would be completely different from ones used in huge warehouses. So we came up with a design concept that incorporates a common platform as a base with a customizable upper portion. Both mobilities are already available for businesses, and many clients have already put them in use.

As for the Postee, it’s not yet available for postal services, but we’re in the process of getting it to market. We’ve already done several real-world verification projects with potential clients.

The micro-mobility Logiee’s operating system can be adapted to better suit a specific industry or task. Here it helps out in the supermarket. COURTESY OF YASUHIDE YOKOI.

For such tiny vehicles, there’s a lot going on in those designs—self-driving, 3D-print body, EV chassis, lidar sensors. How involved are you in each aspect? How do you keep it streamlined?

As an industrial designer, I’m involved in almost every aspect from the very first kick-off to the final implementation. It’s important to take part in the process from the very beginning—even before a project’s official kick-off—in order to keep every aspect and process streamlined and integrated. It has to be seamless.

Have you seen a shift in attitudes about micro-sized vehicles? Europe and Japan seem to have much bigger quadricycle-style markets than the U.S., for instance. How do you approach designing for the existing market versus designing for the expected future market?

From a macro perspective, I believe society and more industries are becoming more aware of these micro-sized vehicles. Essentially, the micro-sized mobility best fits the lifestyle here in Japan: Both cosmopolitan and traditional cities have narrow roads with crowded parking. For another micro-mobility project I did, a collaboration with Honda, the vehicle perfectly fits the needs of the traditional city Kamakura, which is also a major tourist attraction.

Yasuhide’s autonomous, postal delivery EV, the Postee, has hatches on all four sides. COURTESY OF YASUHIDE YOKOI.

You designed for Nikon for several years. What did you learn from that experience? Does that work and the process around it correlate at all to what you’re designing now, or is it a whole new baseline?

I gained a lot of important, essential insights into product design during my seven years at Nikon. For product development there, members from different divisions—engineering, marketing, design—all collaborate as a very close, flat team with no hierarchy or superiority. Of course, the discussion gets messy sometimes, but I found that even the messy parts are essential in order to build good products. I value this process very much, and I’ve been practicing the same style with my current partners and clients.

“It’s important to take part in the process from the very beginning—even before a project’s official kick-off—in order to keep every aspect streamlined and integrated. It has to be seamless.”

On the other hand, there are several aspects that are totally different from the Nikon experience. At Nikon the products were sold on a mass scale to millions of users. So the design had to be universal—sometimes less innovative and more conservative—and there were so many constraints on the manufacturing technology. Ultimately, the goal to create designs in the easiest fashion, to be sold to the most users, was built in as an underlying factor. As I jumped out into independent work and started to adopt 3D-printing technology, not only for prototyping purposes but also for the end product, the goal of each design project—and the mindset underneath—started to change. I now run many projects that focus on niche but important needs, things that can finally be realized through 3D printing. Mindset and process are very important when you’re working in a completely new industry like autonomous mobility.

Yasuhide spent seven years as a product designer for Nikon. COURTESY OF YASUHIDE YOKOI.

Are you a tinkerer in your spare time?

Yes, and not only with industrial 3D printers. I like playing around with my desktop 3D printers, mainly for personal study and to learn form, structure, and functions.

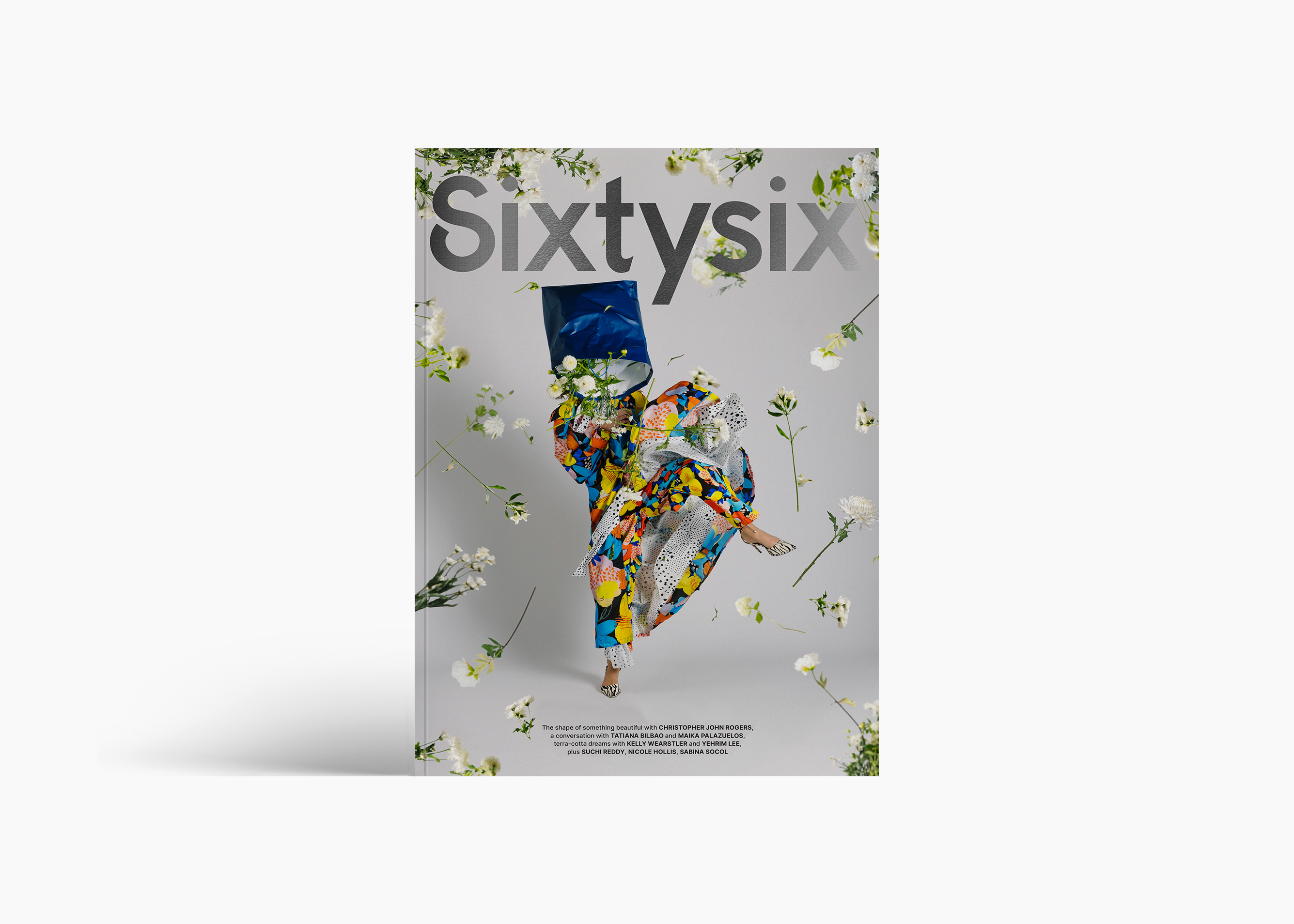

Read more industrial, automotive, and product design stories at Sixtysix.

Have you ever come across a design flaw—either during the development of an idea or just out in the wild—that drove you up the wall?

Many. Especially in my early career at Nikon. On the flip side, I think the definition of a design flaw has changed from then to now. As I said, thanks to 3D printing, and other digital fabrication technology and services, I can quickly recover and update a design onsite with the real users instantly. It’s more like “finding” than a design flaw. For example, during the development of the AI Pilot—the lidar sensor and GPU machine case—after installing the first version, the client soon realized there were new needs, plus they discovered several problems, too, in terms of ease of assembly, internal heat flow, and case warping. We quickly updated the design and 3D-printed the newer version to meet the requests and fix the issues.

The development process is collaborative, intensive, and requires a lot of iteration. COURTESY OF YASUHIDE YOKOI.

You created a katana sword design with 3D printing technology a few years ago. How does one maintain traditional design techniques while using contemporary digital tools?

It’s a Japanese katana sword plus a multi-material 3D-printed sword case. The blade is made by a craftsman who draws on traditional techniques that date back more than 400 years. We used 3D technology in order to connect the opposing manufacturing methods—combining the traditional (katanas are pure analog; not even a single drawing is involved) and the cutting edge into one piece of art. We carefully scanned the handcrafted sword with the latest high-resolution 3D scanner, analyzed the 3D data, and generated the 3D design according to the original. I think it was another ideal case of applying the latest digital technology.

Yasuhide collaborated with a katana craftsman to create a 3D-printed sword case for a traditional blade. COURTESY OF YASUHIDE YOKOI.

Is there any software or design tools that have simplified your process in recent years? Are you a bleeding-edge technology guy or do you prefer a stick-with-what-works approach?

Personally, the 3D CAD software Autodesk Fusion 360 has changed my process dramatically in recent years. It’s a cloud-based 3D CAD software that integrates all kinds of technologies—3D printing plus all kinds of files, including meshes. With cloud technology, I can view and edit the design wherever in an instant and even run heavy CG renderings with cloud-computing power. I’ve also been collaborating and sharing insights a lot with Autodesk, too, and contributing to their conferences and publications.

Yasuhide developed a new line of office accessories for KOKUYO that ‘only could have been achieved with 3D printing technology.’ COURTESY OF YASUHIDE YOKOI.

Tell us about your most recent project.

Together with KOKUYO, a stationery company, we’ve launched a design series of 3D-printed office accessories. The project builds on our concept of “trans tools,” a hybrid of “transformation” and “tools” that goes beyond the common practice of simply replicating existing items through 3D printing and adding some 3D-print-like flavor. We combined the 3D-printing technology used in KOKUYO’s stationery and furniture, which have built up a lot of user loyalty over the years, and evolved them into new tools and expanded their functions. We developed new tool-storage spaces and came up with new uses for items while still keeping their existing functions. For example, we picked up paper clips and file binder parts that make up KOKUYO’s classic core items and applied them to a completely different design: storage boxes. It’s essentially a proposal for the future of office accessories, and it only could have been achieved with 3D-printing technology.

COURTESY OF YASUHIDE YOKOI

COURTESY OF YASUHIDE YOKOI