It was 1977. At the Consumer Electronics Show, then held in Chicago, the world’s first personal computer, the Commodore PET, was announced. Apple Computer was incorporated. Star Wars hit the movie theaters, and Harley-Davidson released the very first Low Rider motorcycle, a bike that would help shift the trajectory of American motorcycling.

Designed by Willie G. Davidson, the grandson of co-founder William A. Davidson, the bike drew on parts from other existing models to create a lighter appearance and a lower seat height. The Low Rider had lowered suspension, forward controls, a black engine, short drag bars, a stepped seat, and a 2-into-1 exhaust. No individual element was groundbreaking, but when artfully combined it created a brilliant new look and an instant classic. In the year it was released it outsold every other Harley-Davidson model.

The Low Rider, and its premium variant the Low Rider S, maintain a faithful following in the Harley lineup. The 2020 Low Rider S gracefully builds on Willie G’s original design with modern updates like the more advanced Milwaukee-Eight engine and new Softail platform. I spoke with designer Brad Richards and Dais “Dice” Nagao at the top-secret Harley-Davidson Product Design Center in Wisconsin about how they’ve navigated the legacy of Willie G’s design with modern technology and trends.

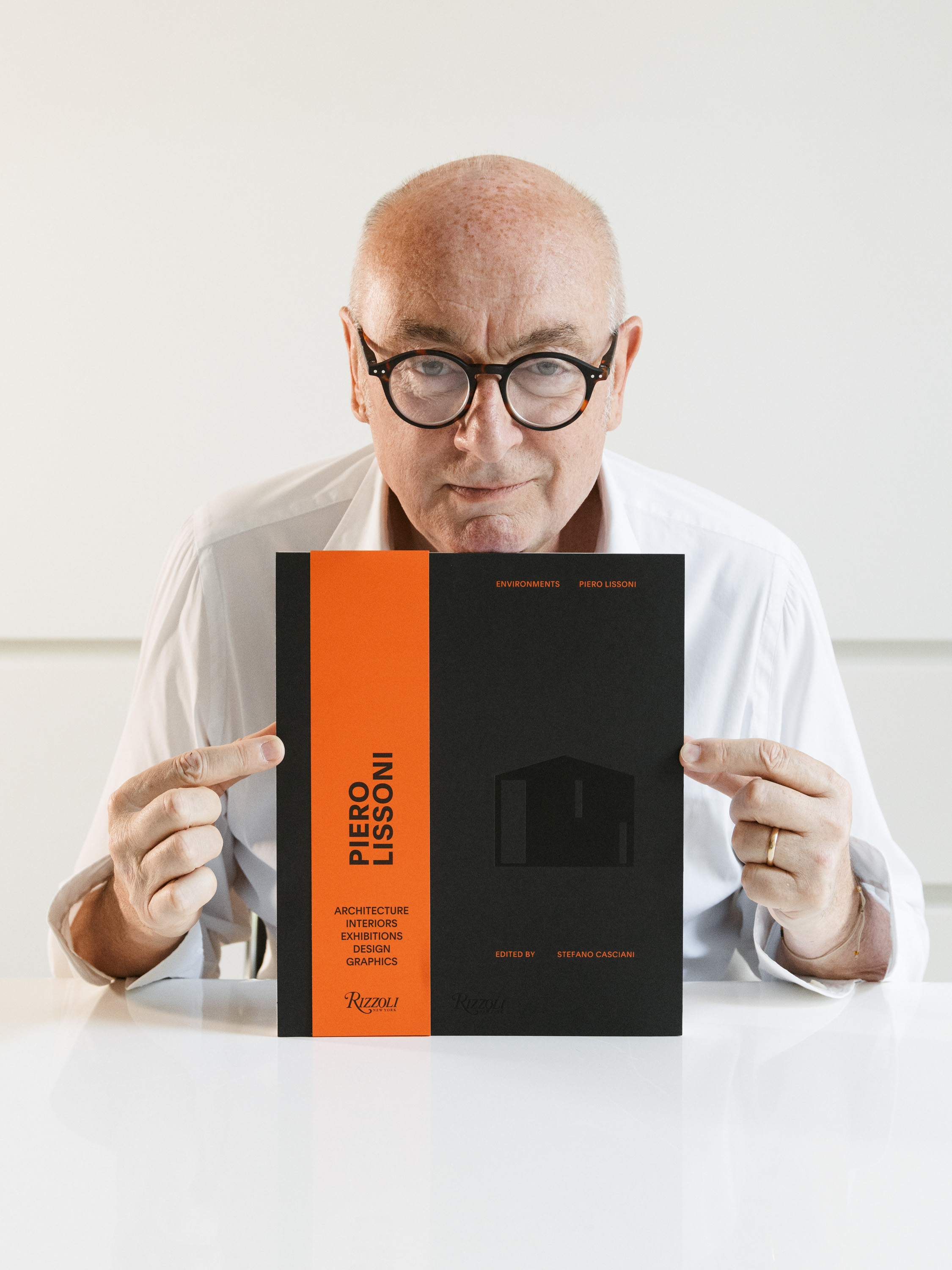

Harley-Davidson lead designer Dice Nagao reviews his sketches of the 2020 Low Rider S. Photo by Chris Force.

Dice, tell me how you came to work on the 2020 Low Rider S.

Dice Nagao, lead designer, Harley-Davidson: Well, I was born and raised outside of Tokyo. I moved to the US when I was 19 and went to college in Iowa and played rugby and studied fine art. After I graduated, I moved to Pasadena to study car design at Art Center College. I graduated and worked for Honda R&D for 10 years before landing my dream job here at Harley-Davidson seven years ago. My first position here was a senior designer. I’m now a lead designer.

Brad, could you explain the hierarchy at H-D?

Brad Richards, vice president of styling and design: The entry-level position we have here is associate designer, then designer, then senior designer, then lead designer. That’s how the industrial design talent structure is organized, into four levels. Right now we are at 26 people; it’s as large as the department has ever been. With all of the new work we are currently executing that’s aligned with the “More Roads” initiative we’ve had to hire up. We have a couple open positions we’re still trying to fill, and all of our design is in this facility.

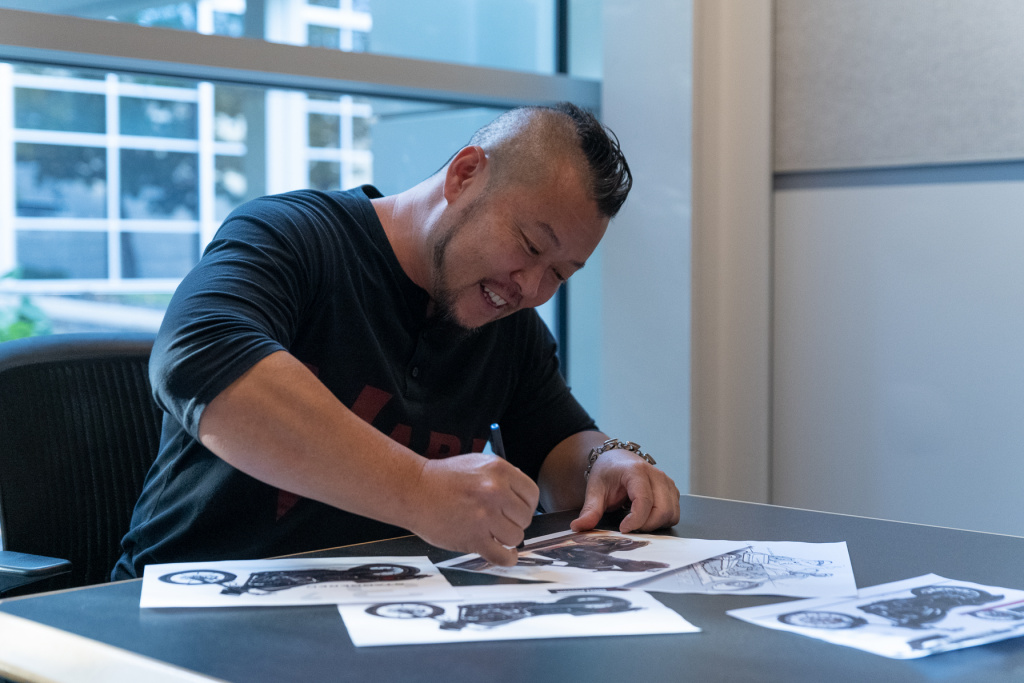

- “No one person designs a motorcycle. It takes an army of folks,” says Brad Richards, vice president of styling and design for Harley-Davidson. Photo by Chris Force.

I assume you’ve relocated a lot of people to Wisconsin?

Brad: One of our challenges is folks who are great designers, especially if they’re younger, tend to live in California. Here in Wisconsin we have three months of summer, and it’s a tough sell sometimes. Before bikes like Pan America and Bronx were out we had a really tough time attracting talent to the studio. As soon as that stuff hit we started getting bombarded with portfolios and resumes. It’s been very easy to staff up after that; we’ve had to say no to a lot of folks. We’re super picky, we look for extremely talented industrial designers, and then within that pool you have to find a transportation designer, then a good motorcycle designer, then someone who understands Harley-Davidson. That final step is the hardest step.

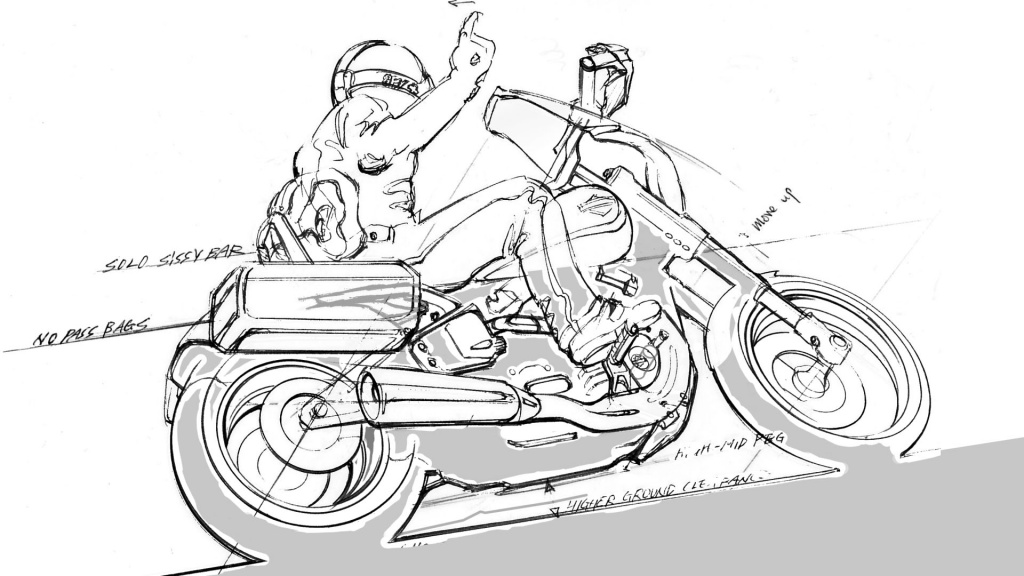

A drawing of the 2020 Low Rider S by Dice Nagao. Photo by Chris Force.

Besides technical ability, what do you look for in designers?

Brad: You need to understand the brand. You need to have a working understanding of the history and heritage of Harley-Davidson. We don’t try to hire evangelists, guys like Dice bleed orange and black, but he has appreciation for other brands. Before I got here I’m not sure how open the design team was to hiring anyone than just “Harley guys.” But I’ve been really open to it because we have to start thinking about other customers, folks who are sensitive to other genres and other parts of the world and other motorcycles. But they do need to understand history and context because everything we do, we try to stitch it back into the narrative of the brand. Narrative is weighed heavily.

Related | Dave Mucci and the Art of Custom Motorcycle-Building

Dice, what are the big projects you’ve worked on?

Dice: The tail-end of the concept bobber street bike called Garage. Then the Iron 883, the CVO Softail Cross Street, the Breakout Pro Street, and the original Dyna Low Rider S. I’m mainly on big twins, cruiser, touring, and CVO (H-D’s custom vehicle operations line of factory customs).

A sketch by Dice Nagao for the 2020 Low Rider S. Note the solo sissy bar and 2-into-1 exhaust. Image courtesy of Harley-Davidson.

When you came in Harley-Davidson was still using the Dyna platform, which over 26 years had grown a rabid, almost cult-like following. Though the public didn’t know it, the Dyna Low Rider S would be the very last Dyna the company would make before moving to the Softail platform. How did that impact your design process?

The Dyna Low Rider S was my fantasy. It was easy for me to come up with the theme of that Dyna. Coming into the organization as the new guy, knowing that platform was going to be canceled, I said, “No way! What can I do?” I sketched a performance-based Dyna. I had so many meetings to pitch it, but they were all dead ends. But when Brad came onboard, he knew what I was working on. I had a 10-page deck that was the genesis of Low Rider S, and Brad and the team came up with a program to squeeze that last out of Dyna and make it happen. Every time I talk about it I get emotional because I’m glad that happened.

Brad: I came on about the same time as Dice, but he’d been sketching performance bikes before that. He’s got a real passion for performance, it’s trending now, but he always had that. We knew Dyna was ending and we wanted to do something special. There were some people in the company who didn’t quite understand why this was a historical moment, so initially some of the work Dice did had to get in front of the right folks. I came in and met with the designers, and I knew instantly we had to do this motorcycle.

The 2020 Low Rider S, shown here in vivid black, has a base price of $17,999. Black is certainly the theme—the powertrain, primary cover, and tank console are finished in Wrinkle Black; the derby cover, intake, and lower rocker covers are Gloss Black. Mufflers and exhaust shields are Jet Black. Forks, triple-clamp, riser and handlebar, and rear fender supports are Matte Black. Photo courtesy of Harley-Davidson.

As it turned out, the Dyna Low Rider S had a short shelf life, coming out in 2016, gaining this cult following, then disappearing when the Softail platform was released in 2018. Was there any thought of rolling it out in the ’18 lineup?

Brad: No. Softail was pretty far along, almost every model that was happening in 2018 was baked. I didn’t really have a whole lot to do with those bikes; they were pretty far down the path. We all knew we had something special with Low Rider S, but the reality was we were so far down the model year we didn’t have the bandwidth to pull it off. But we debated it.

It was nice to have a little gap, but at the same time we got a lot of pushback on the name Softail. I think having the Low Rider S in the lineup would have quieted some of that.

Looking back do you wish the Low Rider S had come out then?

Brad: The decision was made, and you could probably argue it both ways. But I’m really glad we’re launching it right now. It’s a great moment. The absence of a nimble, lightweight performance bike went away for a moment. Don’t get me wrong, the other bikes perform, a Heritage will blow your mind, but the absence of that bike meant when we did unveil it there was instant love for it.

- “This bike was really inspired by what’s going on in the street,” says Brad Richards. Photo by Chris Force.

When did the formal design process happen for the Softail Low Rider S?

Brad: We were working on it the moment we finished the Dyna version. We debated a few things, for instance, the rake between 28 and 30. We built two mockups. I wanted 30, the young guys wanted 28, and they convinced me. And thank god, because it was the right move. I wanted the old ’77 Low Rider, but they’re coming from a different point of view, and it’s more on trend. That’s the beauty of working with diverse opinions.

So this was happening in 2018?

Brad: Yeah, it was the summer of 2018. By October we had a final theme. It was fast. We had all the parts. We had a great front end from the Fat Bob, we had an awesome chassis, killer powertrain, we had to retrim a rear fender. That’s a cool thing about working at Harley-Davidson. When you create a family of motorcycles you have an open palette of parts you can start riffing on. It’s what our customers do, and they inspire us. This bike was really inspired by what’s going on in the street.

[rp4wp]

How did you gather outside feedback for the Low Rider S?

Brad: No one person designs a motorcycle. It takes an army of folks—folks from consumer product planning, they go out and look for whitespace and try to get the right analytical data in terms of what we do next. They also look at trends. They work in this building, but they report to marketing. They represent the voice of the customer. But this program was a little unique. It’s what we call a “quick to market” program. It’s something we’re getting better and better at, something we’re authenticating. It enables us to be pretty quick once we spot a trend. For the Low Rider S we knew what we had when we did the first one, so we didn’t do deep research. We knew people loved it. It was obvious. Other bikes we do a ton of research; especially when we’re getting into new platforms like EVs, we go very deep.

In terms of going up through the company to bless a motorcycle there is a product development process we follow. It comes down to the size and scope of the project and how many people are in that process—how many engineers, how many marketing folks, how many designers. Once you have what we call a final theme sketch, that establishes design intent. We take that into a senior leadership meeting and the team presents the sketch. We take input and try to gain alignment from the leadership team that the sketch does indeed establish design intent. Once everyone at the table blesses it, which happened with the first and second Low Rider S, that sketch goes out to the rest of the teams at Harley-Davidson who are responsible for bringing it to life.

- The LED layback tail lamp has a smoked lens. Photo by Chris Force.

- A mini speed screen wraps the LED headlight. Photo by Chris Force.

What does that presentation look like? What are the tools you use?

Brad: We typically have a really nice sketch, if there’s research we go over research. There is usually a deck that is collection from other departments. Someone has to go over the business, how the project is going to make money. Sometimes we have mockups, but usually it’s just sketches at this phase. Further down the line we will normally show a physical mockup and then from that engineering will show their mockup. We put both of those mockups together and step back. They need to look identical, and if they don’t, we have a conversation about that.

Do you remember any of the feedback from that meeting?

Brad: I do. Some bikes are just slam dunks. “Let’s get it to market as quick as possible.” There are always questions about the business case, take rates, capitalization.

When you get those types of questions, how silent is the design team in those moments?

Brad: (Laughs) It depends. We’re always very passionate about what we bring to those meetings. We put our blood, sweat, and tears into those things. So as vice president I try to answer any questions that may affect design. The emotional part of Harley-Davidson, that is our world. There are finance people in those meetings, the finances are their world. They’re experts. But we do sometimes get into conversations about content, can you deliver this, what’s the right thing for Harley-Davidson. The only thing we changed was someone said, “This bike is so cool, why don’t we offer it in two colors?” So we took a look at a lighter color.

It takes a lot to get everyone together and we can only do it once a month. But this one was really just a slam dunk. Color is where we get some feedback from the Consumer Program Management folks, because they are really tight with the dealers, like, “Hey, Southern states want a lighter color.” We knew we had a dark color that was a hit, so we figured we should try a lighter color, which is how we landed on Barracuda Silver. Every year we have a team who does all the colors and finishes. Getting a color ready for production, going through all the testing, takes a long time. Years. It’s an entire program. We really want it to be premium. So we had to pick something that already had been worked out, and we felt Barracuda Silver worked, so we ran that by Dice, too.

Dice: There were a lot of upgrades on the front end compared to the Dyna Low Rider S. It’s got an inverted front end with a 28-degree rake with a dual disc brake in the front. That’s the biggest hardware upgrade that supports the dynamic performance of the bike. You know it’s a hot rod. Not in the traditional sense that it just goes, it’s also turns and stops. That’s a really valuable upgrade.

Though the design intent may have envisioned canyons in Southern California the 2020 Low Rider S fits in fine on two-lane blacktop in rural Wisconsin. Photo by Chris Force.

How did you decide to put forward controls on the bike?

Dice: It’s a delicate thing, a lot of regulations and requirements, selling the bike internationally. That was a tough, I wouldn’t say compromise, but a sweet spot, to keep that chin-up rider triangle and still meet the other requirements. We did the hard part, which was changing the handlebars, moving from a drag bar to a moto bar. That rider position, Harley owns that genre. Customers and history can guide us: What’s the right posture for the bike? That’s why sometimes I put riders in my sketches, just to create the package with the rider on it.

In what ways was your original rider triangle different than what got produced?

Brad: We were pushing around the idea of a high riser. But there are requirements and product integrity you have to stick to, they have to be safe and legal. There’s also always the P&A (parts and accessories) team who wants to save stuff for folks to buy from their catalog. The good news was the Softail chassis was 90% stiffer, it’s lighter, the motor is more tractable, so we had all these core ingredients that were free with the package.

Dice: I think we did the hard part. We gave the customers what they want. The biggest difference between my sketches to the final product is the exhaust system. All my sketches have 2-into-1 systems. But do we spend that much resource and negatively affect the MSRP, when customers can easily pay $750 to put their choice on? We did what we could. We got the inverted front end, the dual disc brakes, the moto bar, a slightly longer rear fender—that extra inch was a big deal. We tried to get the bike up off the ground as high as we could. We centralized the license plate, and we all wanted this graphic on the tank—that’s something the customer can’t easily do themselves. One strong pushback from engineering was the 28-degree frame, because it was an added expense from the factory. We had to fight for that one.

There wasn’t already another 28-degree frame?

Brad: Fat Bob is 28 and inverted. But it has a 16” wheel, and this is a 19”.

Dice: That was a hard pushback, but I feel good about it. Without 28 this bike wouldn’t have hit the mark.

Is there a clear geographic home where this bike is most successful?

Brad: Southern California.

When you get a design brief from what the company is looking for, does it ever include a personality profile?

Brad: Consumer Program Management does have personas of our customers. They are delivering the voice of customer, what they are thinking, and what they are trying to solve with the motorcycle.

So who is this customer? What do they look like?

Brad: It’s a person who values function. Typically a younger rider, it trends like 10 years younger than our Street Glide, for instance. A younger demographic, someone who really is interested in function versus “look at me.” The whole coastal style motorcycle thing that started in 2003–2004 was a reaction to the biggest trend then, the whole “look at me” super loud bagger, giant wheel, big sound system.

What do you know about how the motorcycle is actually being used?

Brad: The thing has to corner, it has to be nimble. A big motor in the smallest Harley we can make. It’s got to stop. Luggage isn’t something people are super concerned about. The base motorcycle is all about getting through the canyons as fast as you can with a Harley-Davidson attitude. Lane splitting.

Is it too early to say if this bike hit its sales goals?

Brad: It’s too early, but hey, we’re making more!